Drew Valentine is running the Loyola University men’s basketball team through a series of drills. It’s June, but there’s a midseason-like intensity to the practice. Wind sprints. Defensive stops. Valentine doesn’t like what he’s seeing, and he lets his players know, in R-rated language.

“Nobody over here gives a fuck,” he shouts, sounding more disappointed than angry. “Everybody over here just worried about themselves and not the fuckin’ team.”

At 31, Valentine is the youngest coach in Division I — so young that one of his friends says, “Drew could put on a Loyola uniform, and no one would blink an eye.” That’s not quite true: He’s burlier than his players, more thickly bearded. But unlike many college hoops coaches, some of whom are plausibly old enough to be a grandparent to their players, Valentine is a millennial overseeing a group of Gen Zers. He can chop it up about rappers like Lil Durk and G Herbo at team dinners, and he wears the same sneakers his players do. That’s off the court, though. On the court, he can sound as old-fashioned as Bob Knight.

“Bryce, what the fuck are you thinking?” he asks Bryce Golden, his prize transfer from Butler, who was out of position on an offensive setup. “Why does Braden [Norris] have to tell you where to go every time? I’m not fuckin’ dealing with that. Who the fuck do you think you are, lookin’ at me like that?” Golden drops his head.

It’s not all swearing and sarcasm, though. When Valparaiso transfer Sheldon Edwards makes a strong defensive play, Valentine slaps his hand.

The second-year head coach has been with the Ramblers since 2017, when he was hired as an assistant. That season, Loyola reached the Final Four. Before that, the Rogers Park school was such a mid-major obscurity that one of the players on that team, Lucas Williamson, had never heard of it before he was recruited, even though he grew up in the South Loop and went to Whitney M. Young Magnet High School. But this is a new era, and expectations are high. This season, Loyola is switching from the Missouri Valley Conference to the Atlantic 10, a more competitive group of schools that includes Davidson, Dayton, St. Louis, and VCU. The conference’s higher profile could help the Ramblers secure better recruits and more March Madness bids — or it could push them back into obscurity, overwhelmed by stiffer competition. Whether Loyola succeeds largely rests on the shoulders of its young coach.

At the end of practice, Valentine gathers his team. Twirling the lanyard of his whistle around his forefingers, he glares at the circle of anxious-looking players.

“I’m very disappointed in how some of you handled adversity,” Valentine says. “This shit ain’t easy. We don’t have all the things for a championship team. I know what it fuckin’ takes.”

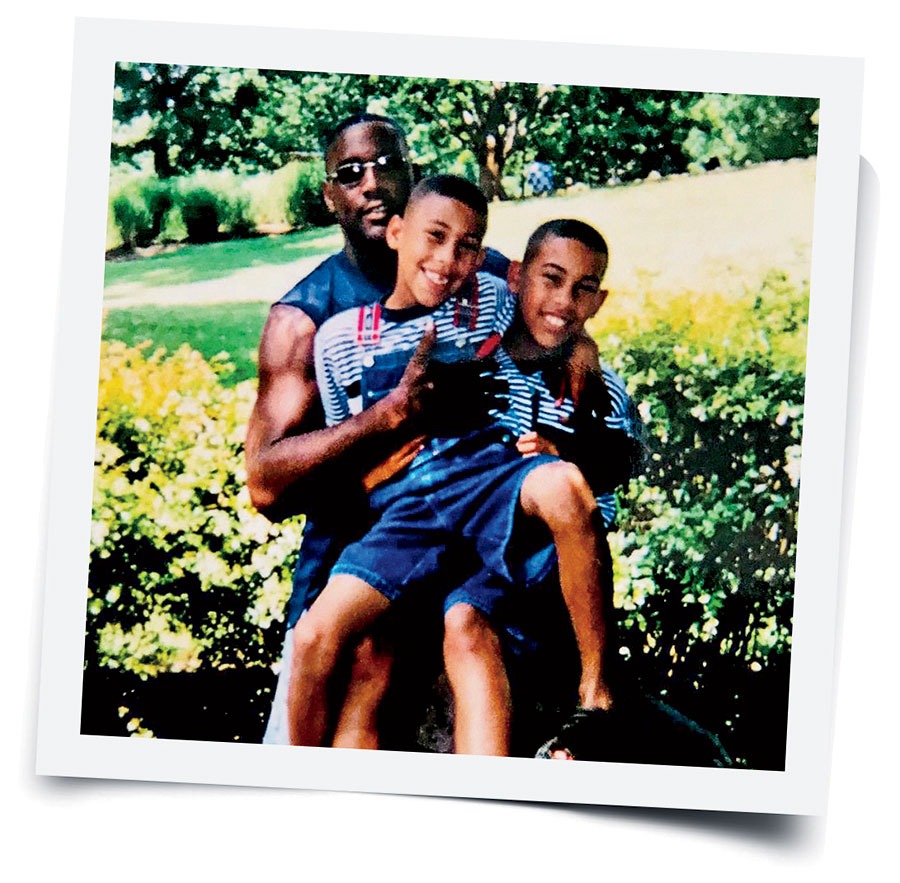

Standing in the back of the gym is someone who knows — better than anyone — that Valentine does know what it takes. It’s Valentine’s brother, Denzel, a former Michigan State star who was a lottery pick for the Bulls in 2016, though he never developed into more than a role-playing guard. Denzel, who is two and a half years younger than Drew, is back in Chicago to work out with his brother, who’s helping him train for one last shot in the NBA. From the time they were old enough to dribble a ball, Drew and Denzel were, in the words of a childhood friend, “raised in a lab to be basketball minds” by a demanding father whose own career stalled one step short of the NBA.

“My family’s life changed forever because of the way we fuckin’ grind,” Valentine tells his players.

With that message delivered, he dismisses his squad for the day. Exhausted, his players lope toward the locker room. March is a long way away.

By the time they each turned 3, the Valentine brothers had basketballs in their hands. Soon their father, Carlton, began drilling them in the fundamentals. Pull-up jumpers off the dribble. Dribbling through cones while crossing over between the legs. Straight-line accelerations. This was in the ’90s, during Michael Jordan’s heyday. Basketball was becoming a guard’s game. A former Michigan State standout, Carlton made Drew and Denzel practice at least an hour a day as they were growing up in Lansing, Michigan.

“Just give me an hour and you guys can go do what you want,” Carlton told his sons, “but just give me an hour of fundamental work.”

Their mother, Kathy, didn’t understand why Carlton threw footballs at her sons as hard as he could, a drill intended to sharpen their reflexes.

“I know what I’m doing,” Carlton insisted.

“What you’re doing is hurting my babies!”

Drew, whose full name is Carlton Andrew Valentine II, didn’t understand, either. Why, he wondered, couldn’t his dad just be a dad? But Carlton never stopped coaching.

“Coach V was really intense, very detail oriented,” says Jordan Howenstine, a teammate of Drew’s at J.W. Sexton High School in Lansing, where Carlton coached them, and at Oakland University and now the basketball communications manager for the San Antonio Spurs. “He saw from a very early age that his sons had a lot of potential.”

Carlton would take them places other kids couldn’t go, too. As a former Spartan, he’d bring them into the Breslin Center locker room, where they mingled with the players and visiting star alumni like Magic Johnson and Steve Smith. “Carlton was a disciplinarian,” says Tom Izzo, who took over as Michigan State’s head coach when Drew was 4. “He’s tougher than nails. He held those kids accountable.”

As an assistant at Michigan State, Izzo had recruited Carlton out of DeMatha Catholic High School in suburban Washington, D.C. Carlton played on losing Spartan teams his junior and senior years, then graduated into the low-paid nomadic life of pro basketball’s underclass after a tryout with the Indiana Pacers went nowhere, enduring bus rides and tiny gyms for the Illinois Express and the Saskatchewan Storm of the now-defunct World Basketball League. After Drew was born, Carlton went back to playing professionally in Sweden. But when Kathy became pregnant with Denzel, he decided it was time to settle in Lansing, where his wife had a job as a schoolteacher.

His own basketball dreams over, Carlton was determined to give his sons the best shot possible. “I wanted them to be able to play guard and play multiple positions — because I was undersized, a forward being 6-5, 6-6 — just to have better opportunities than I had,” Carlton says. “I just wanted to make sure they had the skills necessary to succeed in basketball.”

It wasn’t always easy growing up Carlton’s son, but looking back, Valentine recognizes some of his father in himself. “We were just held accountable at an elite professional standard,” he says. “I felt like I was treated like a pro from the time I was 10 years old. My dad was always hard on us. As I got older, I understood the why, and I really appreciate now the fact that he did that. When we got to the games, he gassed us up and hyped us up and gave us a lot of confidence. That’s a lot of what my coaching style is: I’m gonna hold you to a really high standard every single day in practice, and then when we get to the game, I’m gonna want you to play with a lot of swag and a lot of confidence, because you put in the work, and you deserve to win.”

“I felt like I was treated like a pro from the time I was 10 years old,” Valentine says. “My dad was always hard on us. As I got older, I understood the why, and I really appreciate now the fact that he did that.”

Even before the boys reached their teens, Carlton’s incessant drilling was showing results. One weekend, he took his sons to a youth basketball tournament in Indiana, where Denzel slickly flicked passes all over the court.

“Denzel’s got that thing,” Carlton told Kathy when they came home.

“What do you mean, he’s got that thing?” she asked.

“He’s special,” Carlton said. “He’s different.”

“Well, Drew is different, too.”

“Yeah, Drew’s really good, but Denzel’s got that thing.”

As a player, Drew never quite developed that thing. But he had another thing. He was assertive, a leader. When a neighborhood kid stole Denzel’s Pokémon cards, Drew marched over to his house and took them back.

“I always knew he was going to be a coach,” Carlton says. “When he was 5 years old, he was on the basketball court at preschool, showing guys what to do. Even when we would go out in biddy ball, YMCA, he would be putting players in place.”

Drew wasn’t yet done playing, though. In high school, he also quarterbacked the football team, and during his senior year he tore his ACL — the first of a series of injuries that would eventually convince him his future was in coaching. Still, Valentine played Division I college basketball at Oakland, a mid-major Horizon League team. (“I wasn’t good enough for Michigan or Michigan State.”) Meanwhile, his younger brother’s basketball career was taking off. While Drew was in college, Denzel won two high school state championships, started beating his big brother in one-on-one, and earned a scholarship to Izzo’s Michigan State.

Izzo had known both Valentine brothers since they were toddlers, and he hadn’t forgotten about the older of the two. In 2013, after his senior season at Oakland, Drew traveled to Indianapolis to watch Denzel’s Spartans play Duke in the Sweet 16 of the NCAA Tournament. After the game, which Michigan State lost, he ran into Izzo at the hotel — and Izzo offered him an unpaid job as a graduate assistant. The kid seemed like a hard worker, Izzo thought, and he was Carlton’s son, so the coach knew he had the basketball chops.

Valentine didn’t immediately agree to take the job. He already had a contract to play professional basketball in Germany. But if he went overseas, he’d first need to recover from a serious injury. During his senior year, he had torn his meniscus. He underwent surgery that April, but by July, the knee wasn’t responding. It was time, he realized, to stop playing and start pursuing his coaching ambitions by joining Izzo’s staff.

Denzel recalls what Drew was thinking: “He was kind of like, I’ve already put my body through a lot, and my brother’s going to be playing at the school that I’m going to coach at, and I’m going to be learning from a Hall of Fame coach. Do I really want to go overseas and be away from my family, or do I want to start at a young age, help my brother, and then get to my goal as fast as I can?”

It was just as their father had foreseen: Drew was the coach, Denzel the player. And Izzo saw to it that Denzel didn’t get special treatment from his older brother. Once, when Denzel goofed off, Izzo told Drew to straighten him out — and indeed he did. (Neither brother will offer details of the infraction, but both say Denzel learned his lesson.)

“Hey, that’s your job,” Izzo told Drew. “You’re not his brother, you’re his coach.”

Valentine was learning that he could be close to a player while still being a demanding motivator. He was, as Izzo puts it, “very good at walking that fine line.” And he was getting results: By his senior year, Drew had helped Denzel become one of the best players in the country. That season, Denzel was named the Associated Press Player of the Year.

“Drew worked Denzel out every single day, individually, him and [teammate] Bryn Forbes,” Howenstine says. “I don’t think either of them would have been in the NBA without Drew. Denzel went from an average player to Big Ten Player of the Year. Drew took this raw product and made it into an art piece.”

For Valentine, the experience helped him realize that a career in coaching wasn’t just a dream. “It gave me a ton of confidence that I could do it,” he says. “I was good enough.” Soon Denzel was on to the NBA. The brother who helped him get there may not have been headed to the pros — he didn’t have “that thing” — but he was making moves of his own.

It’s a Thursday during the offseason, and Valentine is in his office. Basketball season lasts only a few months, but college coaching is a year-round occupation. Valentine’s corner office inside Loyola’s Joseph J. Gentile Arena is mostly empty of coaching swag, except for a championship plaque from the 2022 Missouri Valley tournament. Older coaches do business in rooms full of hardware, but Valentine is still too new to have accumulated much of that.

Valentine is 6-foot-5 — tall for the world, but not for a basketball player — and feels lucky to have grown that high, since his mother is only 5-4. He’s wearing a pair of black-and-white Nike Dunks, which sell for more than $150. This is a significant detail because, as he puts it, he grew up in hip-hop culture, at “the intersection of sport, fashion, and basketball.” Valentine owns 150 pairs of sneakers, which he stores in two closets at his house in Glenview. (Howenstine calls his childhood friend a “historian of sneakers.”) Travis Scott Jordans are his favorites. He wears a different pair to every game, as a complement to his quarter-zips and skinny khakis.

Valentine is also so knowledgeable about hip-hop that when Howenstine needs music for the Spurs’ media day, he calls his old high school teammate, who sends back a Spotify playlist featuring the likes of Future and Moneybagg Yo. Drew and his brother have identical tattoos, a heart-shaped basketball with the legend “Valentine.” His style is in sharp contrast to those crusty coaches wearing slacks and loafers — including, importantly, on the recruiting trail.

“His favorite rapper is Drake,” says senior guard Braden Norris. “Whenever Drake drops something, he’s always talking about how he’s the GOAT. As a player, that stuff is really cool. It just makes the relationship that much easier with your coach.”

Valentine arrived at Loyola after two years on Izzo’s staff and two years at Oakland as a full-time assistant under longtime head coach Greg Kampe. Bryan Mullins, then Loyola’s head assistant, had met Valentine while both were scouting high school players in Michigan and recommended him to Porter Moser, the head coach at that time. “I thought he was very mature for his age, and passionate about coaching and teaching,” Mullins says.

In Loyola, Valentine saw an opportunity for professional growth. But naturally, his family factored into the decision. With the Valentines, it always does. This would be a chance for him to reunite with them in Chicago. After Denzel joined the Bulls, Kathy moved here to work as his personal assistant. Mother and younger son lived in the same West Loop apartment building, but on different floors. Drew had just gotten married, to Taylor Galloway, a volleyball player he met at Michigan State, and after moving to Chicago, the couple started hosting Drew’s mother and brother for Sunday dinners. Denzel came to Loyola games and told the players what it took to make it to the NBA. Walking the streets of Chicago, Drew was often mistaken for his younger brother.

Valentine’s first year with the Ramblers, the team went to the Final Four for the second time in school history. (The first time, in 1963, Loyola won it all.) Nearer to the players in age and background than the rest of the staff, Valentine was seen by many on the team the way Denzel saw him — as an older brother. As Loyola’s defensive coordinator, he became especially close to Lucas Williamson, who joined the team the same year, and he helped the young player develop into an elite defender.

“We’re two city boys, always trying to prove themselves,” Williamson says. “We have similar mentalities. I could always come to him with questions, advice, problems, whatever. With a Black head coach, you talk about recruiting, and being able to relate to someone, that matters.”

“Whenever Drake drops something, [Valentine is] always talking about how he’s the GOAT,” Loyola senior Braden Norris says. “As a player, that stuff is really cool. It just makes the relationship that much easier with your coach.”

When Mullins left for Southern Illinois in 2019, Valentine became Moser’s heir apparent. So it was no surprise that within hours of Moser’s April 2021 announcement that he was taking the helm at Oklahoma, Valentine, then 29, was introduced as Loyola’s new head coach — the only Division I men’s basketball coach under 30.

“Drew, when he got here, he was already someone who was on a real upward trajectory,” says Loyola’s athletic director, Steve Watson. “Porter said, ‘He’s got a real high ceiling and a lot of potential.’ You knew he was going to be a head coach. It was just when and where. We knew if Porter left, he was the natural successor. It was a no-brainer and a formality.”

For Valentine, it was the fulfillment of a goal he’d had since taking the Michigan State graduate assistant job. But he had never expected it to become reality so quickly. “I didn’t get into coaching and say, OK, I’m gonna be a head coach by 30,” he says. “Once I started working with the players and saw the results, I was like, Man, I think I could run a program one day. You’d see the young coaches that were getting hired, and I thought the way they described those coaches was similar to some things that I brought to the table, and I thought I could bring even a different swag and presence and energy and vibe than them.”

It was, however, a fraught time for Valentine. Ten days after he was hired, his wife gave birth to their daughter, who was 11 weeks premature. The newborn had to spend the first three and a half months of her life in the hospital. She’s healthy now, though doctors are still monitoring her development.

As Valentine cared for his family, he was also trying to keep his team intact. It was the first year of the transfer portal, which allows players to change schools without taking a year off, and college basketball’s giants were looking to pluck away the team’s best players returning from the Sweet 16 squad. Williamson had been Defensive Player of the Year in the Missouri Valley Conference as a junior and could have likely moved up to a big-time program like Villanova or Kentucky. So Valentine spoke individually to every Rambler and his parents about his vision in an effort to persuade his players to stay. They all did.

Valentine’s second task was getting Loyola back to the NCAA Tournament, from a conference that usually gets just one bid. The new head coach quickly realized that he couldn’t just be the cool older brother anymore. He had to push his players more than he ever had as an assistant. Sure, he could still talk Drake, but he also wouldn’t hesitate to get tough with them during practice or games.

“Everybody wants to be a players’ coach, relate to the player,” says Izzo. “Those guys don’t usually win a lot of championships. He’s got to be his own guy. He’s got to be tough. I think with Kampe and myself and Porter, he’s learned that.”

Valentine’s players appreciate the tough love. “He’s super demanding,” says Norris. “One of the best things about him as a coach is that on the court he’s on us big-time, and everyone has that respect. That starts with the older guys: As long as we’re respecting him, the younger guys are gonna fall right in.”

Loyola finished the regular season 25–8, including a 1-point loss to Izzo’s Spartans, and were fourth in the Missouri Valley Conference. But the Ramblers secured an automatic bid to the NCAA Tournament after winning Arch Madness, the conference’s postseason tournament in St. Louis, making Valentine the youngest coach to take a team to the Big Dance in 30 years.

The Ramblers, a No. 10 seed, ended up losing in the first round to Ohio State, 54–41. But while the season ended with a historic dud (Loyola became the first tournament team ever to shoot worse than 30 percent from the field, 3-point arc, and free-throw line in a game), it’s hard to characterize Valentine’s first year at the helm as anything other than a success. Loyola had been to the NCAA Tournament only seven times before.

It isn’t going to get any easier, especially with the Ramblers joining the Atlantic 10. Key players, including Williamson, have graduated. But there’s also an opportunity for the young coach to make this team fully his. “How does he recruit? How does he relate when he doesn’t have experienced players?” Izzo says. “The next part’ll be tough, but he has a really good year under his belt.”

Valentine’s first full off-season as Loyola’s head coach was a busy one. In June, he flew to Las Vegas to see Williamson play in the NBA Summer League with the Los Angeles Clippers. (He wound up in the G League.) Later, the Ramblers played three exhibition games in France, against professional teams. And Denzel, who played in the G League last season, came to Chicago for three weeks of one-on-one workouts with his big brother to prepare for training camp with the Boston Celtics. (He was later waived and is back in the G League.)

Valentine also set out to improve his squad. In addition to a trio of three-star freshman guards he had already recruited (Jayden Dawson, Trey Lewis, and Jalen Quinn), he brought in Golden as a fifth-year graduate player. The 6-foot-9 center averaged 8.8 points and 3.6 rebounds last season for Butler in the Big East. Valentine also landed a top local prospect for next season: Miles Rubin, a senior at the perennial Chicago Public Schools powerhouse Simeon Career Academy.

Golden appreciates that Valentine is “a young head coach being able to relate to me, not being too far removed from the shoes I’m in now,” he says. “We clicked right off the bat, talking about life, hoops, music, things like that. He’s a young, hungry guy. We talked about having our chip. He’s got that chip on his shoulder.”

Few expect Valentine to stay in Rogers Park for life. It doesn’t take much of a leap to imagine him as a successor to the 67-year-old Izzo. “I can definitely see him being the head coach at Michigan State,” Denzel says. “He has everything in his favor. He’s played. He’s coached at a Division I school. He’s learned from a great coach. And he’s from Lansing. So why not?”

Izzo, too, envisions a bright future for his former protégé. “Drew’s going to be destined for some big jobs,” he says, without specifying that his own might be one of them. Izzo just signed a five-year deal, and Valentine, for his part, says he’s thinking only about his current job: “I’m honestly just focused on being the best coach at Loyola.”

So it’s early for such speculation. Valentine still has plenty to prove. A single NCAA Tournament appearance isn’t enough. Valentine has to keep winning at Loyola. And to keep winning at Loyola, he has to keep pushing his players, just the way his father taught him.