Last May, William M. Daley, the mayor’s youngest brother, took a new job as the top Midwest executive of J. P. Morgan Chase & Company, and for the first time in more than two decades, he did not play an active role in the Presidential campaign. Nonetheless, Daley’s experience and reputation for political shrewdness kept him in demand, and Jim Johnson, a top John Kerry adviser, called for counsel when the Kerry camp was negotiating the format for the Presidential debates. Above all, Kerry’s people wanted three debates—three chances to show up President Bush and to introduce Kerry to voters. The Bush camp wanted as few debates as possible and would agree to three only if the Democrats acceded to certain arrangements—among them, that the first debate would focus on national security, and lights and buzzers would be used to keep Kerry to a strict time limit. But Kerry’s aides opposed the Bush demands. Enter Bill Daley, whose response was quick and sharp: “Every single thing that the Bush side wants is good for Kerry. If I were you, I would take the third debate and agree to everything and end the negotiations in five minutes.”

Last May, William M. Daley, the mayor’s youngest brother, took a new job as the top Midwest executive of J. P. Morgan Chase & Company, and for the first time in more than two decades, he did not play an active role in the Presidential campaign. Nonetheless, Daley’s experience and reputation for political shrewdness kept him in demand, and Jim Johnson, a top John Kerry adviser, called for counsel when the Kerry camp was negotiating the format for the Presidential debates. Above all, Kerry’s people wanted three debates—three chances to show up President Bush and to introduce Kerry to voters. The Bush camp wanted as few debates as possible and would agree to three only if the Democrats acceded to certain arrangements—among them, that the first debate would focus on national security, and lights and buzzers would be used to keep Kerry to a strict time limit. But Kerry’s aides opposed the Bush demands. Enter Bill Daley, whose response was quick and sharp: “Every single thing that the Bush side wants is good for Kerry. If I were you, I would take the third debate and agree to everything and end the negotiations in five minutes.”

Excellent advice. Kerry won the first debate—the lights and buzzers helped keep him on point—and his floundering campaign reaped a desperately needed lift. “Bill makes no traditional assumptions—what’s possible, what’s not possible,” Johnson says today. He’s “willing to take risks that many people won’t imagine.”

A first-string team of politicians and campaign operatives say much the same thing about the youngest of the seven children of the late Richard J. and Eleanor “Sis” Daley. Indeed, Bill Daley’s particular brand of intelligence presents a curious case: He was never a top student (and he suffered embarrassment 30 years ago when—apparently without his knowledge—a state employee changed Daley’s answers to help him pass the insurance broker’s exam). He maneuvered the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in the U.S. Congress and lobbied on behalf of the telecommunications giant SBC, but his supporters say that he probably never mastered the details of those operations. Still, people who have worked with him (and against him) credit Daley with remarkable savvy. “If you asked Bill the difference between Cicero and Plato, he wouldn’t know,” says the Chicago lawyer and Democratic stalwart Wayne Whalen, but he possesses a “keen intelligence” on how to plot strategy, to predict how people will behave in a given situation, to see beyond conventional wisdom.

As a result, Daley, 56, has played politics at such a high level that his career virtually tracks the roller-coaster history of the Democratic Party through the past quarter of a century. He started small—working in the Jimmy Carter campaign for President, advising Walter Mondale in 1984, then Joseph Biden in his aborted Presidential run in 1988. He became such a favorite of Bill Clinton’s that he sometimes had to decline when the President asked him to play golf or to watch a movie at the White House. Commerce Secretary Bill Daley, appointed by Clinton in 1996, had too much work to do. And he was at the center of the great Democratic disappointment of 2000, serving as the chairman of Al Gore’s race for the Presidency. Today, Daley’s friends say, he can pick up the telephone and call almost anyone, from Arizona Republican senator John McCain to the Citigroup chairman, Sandy Weill. At the peak of the election-night chaos in 2000, Daley called his friend Tom Brokaw, the NBC anchor, to trade the latest news on the Florida returns. Many of his best friends are tough-guy players in the mold of Dan Rostenkowski, once considered the most powerful man in Congress. Danny and Billy, as they call each other, share a love of golf and results; they are what Daley calls results rather than process Democrats—people who want to “get something done,” not people who go to Washington “and it’s all about the purity of the process.”

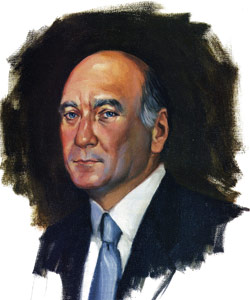

Daley is congenial—when the columnist Mike Royko wrote that Bill and Rich were “too dumb to tie their shoes,” Bill called Royko and told him that he and his brother were “wearing loafers now”—and discreet, and he has a near obsession with order and neatness. Rich might look rumpled, but Bill is always pressed, like a chief executive officer, with his fringe of gray hair coifed, his nails manicured, his shirt monogrammed, and his tie from Hermès. About five feet nine and said to be a StairMaster devotee, he is in good shape, and his eyes are a lovely blue-green. One woman who worked with him says that if they had a political function to go to, she would stay on the job to the last minute and refresh her lipstick; he would go home to shower and arrive looking every inch the power player.

But Daley is a power player with humility, with a reluctance to grandstand so appealing that even his opponents praise him. David Bonior, the former Michigan congressman who led the opposition to NAFTA in the House, recalls a Clinton White House dinner after the agreement passed. Bonior’s wife, Judy, says that she was seated between Bill Daley and a businessman who was “extremely enthusiastic about his position and his familiarity with everybody”; he was bragging that he was a “personal friend of Bill Daley’s.” Bill, whom Judy Bonior recalls as being rather quiet, said nothing; she did not have his restraint. “Maybe you should know, sir,” she said, “that this is Bill Daley.”

For all his success in politics, business, and law, friends suggest, Bill Daley may yet hold some unfulfilled ambitions. At times he has seemed driven to prove that he can make it on his own, without the head start provided by the Daley name and connections. And he may yet have a desire to run for office. When he took the job with J. P. Morgan Chase, kibitzers assumed that he was hired to give a Chicago identity to the New York–based firm, which had just acquired Chicago’s Bank One. Some see him as being paid to be a handshaker and a dispenser of dollars to local charities. But if that is all the position entails, friends say, he will soon move beyond his imposing office at 1 Bank One Plaza.

When Al Gore called Bill Daley in the summer of 2000 and asked him to run his campaign, Daley was the only person on both Gore’s lists of Vice Presidential prospects and campaign chairmen. “That’s a mark of how unique he is,” Gore says. Daley now insists that he was not a serious Vice Presidential contender, and former congressman Tony Coelho, who preceded Daley as the Gore campaign chairman, says that he himself put Daley’s name on the Vice Presidential list merely as “a sign of respect.”

For all its depth, Daley’s résumé lacks the one accomplishment—elective office—that he knows he needs to be seriously short-listed. If his job history had included, say, governor of Illinois, his name would have been added as more than a courtesy.

So in August 2001, when he considered running for governor, it appeared that he was set to fill the gap. “It may sound arrogant,” he says three years later, “but I thought I had a really good shot.” Many pros agreed—among them, former state comptroller Dawn Clark Netsch and Illinois Speaker of the House Michael Madigan.

Other Democrats worried that it might look as if the Daleys were trying to take over Illinois, with Bill running the state, Rich the city, and their brother John, a commissioner on the Cook County Board, the county. “I’m not sure the state of Illinois was ready for a Daley,” says F. Richard Ciccone, a former Chicago Tribune reporter and a biographer of Richard J. Daley. “You go south of I-80, and lots of people would think the Daleys were running the whole state, and they wouldn’t like that.” Rich Daley was said by some to be privately dissuading Bill from entering the race. Today, Bill says those stories are “180 degrees from the truth. He was very encouraging. He absolutely believed I could win.”

Alderman Richard Mell, who was backing his ambitious son-in-law, Congressman Rod Blagojevich, for governor, threatened to “dirty up” the mayor’s brother with talk of his separation from his wife of more than 30 years, reported Fran Spielman in the Chicago Sun-Times. But Bill Daley says his decision not to run was motivated simply by his need to make money. “Contrary to what a lot of people think,” Daley says, “we are not wealthy people, and I needed for personal reasons to try to address that issue.” That led him to his jobs in business, but it may not have permanently quelled the drive to run for high office—an impulse, after all, that goes way back.

Illustration: Shawn Barber

The Daleys are a classic urban Irish American family; the firstborn son, Richard M., was six years older than Bill and destined to follow his father. “If anybody was marched around as the next-generation pol, it would have been Rich, because it’s an Irish family and that’s the way it is,” says Bill’s childhood friend Colleen Dolan. “Bill would have to find his own way.”

As a boy, Bill was “like sunshine,” recalls his sister Pat, “slight, beautiful eyes, and dark hair.” He was the baby of the family, “very inquisitive, a very serious child. He was interested in the world.”

In politics especially, and he was eager to accompany his father, whether to a wake, a parade, or a nominating convention. “He adored his father,” says Dolan. She recalls one summer in Grand Beach, Michigan, where the Daleys had a summer home, complaining to Bill that the political conventions “took over TV.” He insisted that people needed to be informed. In 1960, when Bill was 12, and John Kennedy, a family friend, was running for President, Pat remembers a torchlight parade, and a rally at the Chicago Stadium. Bill was captivated by everything Kennedy said. “‘You’re right, Jack,’” Pat recalls him responding.

After Richard J. Daley became mayor in 1955—Bill was seven then—he and Sis were determined that their children would have normal lives. They walked from the family’s red-brick Bridgeport bungalow to the parish school, Nativity of Our Lord, at 37th Street and Lowe Avenue, and returned home for lunch. The boys played baseball in the backyard and basketball in the alley. They met their friends at the nearby Valentine Boys and Girls Club and at McGuane Park. A neighbor, Harry Brice, recalls that after Bill’s father was elected mayor, the only change was the police presence—cars in front and back of the bungalow.

His mother was more the disciplinarian, Bill says; the mayor was a softer touch. He was most relaxed in Grand Beach, where the man who was seldom seen without a coat and tie could be found in swimming trunks on the shore.

John, a year and a half older than Bill, chose St. Ignatius College Prep for high school, breaking the Daley male tradition of going to De La Salle. Bill followed him to the Jesuit school, which prided itself on its academic rigor. The Daley boys received “no special treatment, not with the Jesuits,” recalls John. At home, the parents monitored the homework. Their father “would know whether you had a test in algebra or Latin,” says John, and when he came home for dinner that night he would ask about it.

John says that his younger brother was extremely quiet at St. Ignatius. Classmates, though, recall that Bill was popular, and he joined the swimming and baseball teams. His baseball coach, Jim Spalding, remembers him as “very conscientious, certainly good enough to make the team, but not a starter.”

“I got through at Ignatius,” Bill says today. “I did OK, not great in any of my academic endeavors.” Robert Connelly, one of his teachers, remembers him in his English class as “above average, a B student, a hard worker.” Spalding, who taught math, says Bill “certainly didn’t set the world on fire as a math student.”

Like his brother Rich, Bill went to Providence College in Rhode Island, but he stayed only one year. “I was not real excited about being away,” he says. Returning to Chicago and living at home, he joined John at Loyola University Chicago, where he majored in political science.

One afternoon when he was a junior, Bill stopped by his father’s office to catch a ride home. Bill “plopped down on a chair to talk,” recalls David Stahl, then deputy mayor, “and asked, ‘Who’s the blonde?’ So I took him out and introduced him to Loretta.” The next time Bill stopped by for a ride, he sat down next to her.

Loretta Aukstik, Stahl’s secretary, had also grown up in Bridgeport; she was a Catholic, and Lithuanian on both sides. Besides being competent and bright, says Stahl, she was beautiful. “The minute he met her,” Colleen Dolan recalls, she and the friends with whom they had grown up knew “it was ‘Bye-bye, Billy.’” They married in December 1970, seven months after Bill graduated from Loyola, and lived in Marina City for a while, then in the two-flat her parents owned at 34th Street and Emerald Avenue. Later they moved north, to the Edgebrook neighborhood, and then, in 1987, to a house in the tonier Sauganash.

On his father’s advice—“Get the degree; they can never take it away from you”—Bill went to law school. He was a good but not great student, without a particular passion for the law. Twenty-six years later, a magazine reporter deconstructing Daley for The Nation wrote that to navigate the “undistinguished halls” of John Marshall, Bill required a tutor and that Mayor Daley was so grateful that he gave the man a judgeship.

The principals say that is not quite what happened. Joseph Gordon, who taught at John Marshall, says he assisted Daley in the subject of evidence for a couple of months, meeting with him once or twice a week. Gordon calls Daley quick on the uptake and says that “a little help went a long way.” Tom Hynes, a colleague of Gordon’s on the John Marshall faculty and later the Cook County assessor, suggested Gordon as a tutor and subsequently helped him land his judgeship. Today, Gordon is an appellate court judge.

Even back then, Daley had a quality that set him apart. Another professor, Ron Smith, remembers recognizing the mayor’s son on his first day of class. He was seated beside “a big, beefy guy” who Smith thought could be Bill’s bodyguard—until he asked for a volunteer and the presumed bodyguard, a classmate of Bill’s, gave a perfect brief. Smith called again for volunteers; this time the case involved an Illinois statute that prohibited civil rights activists from picketing in front of Mayor Daley’s house. “Up goes Daley’s hand,” Smith recalls. “I thought it took guts.”

Daley started as a day student and switched to nights in 1972, when his first child, William, was born. In the summer of 1973, John and Bill opened a Bridgeport storefront, Daley and Daley, to sell insurance. It was “mostly neighborhood business,” Bill says, “auto, homeowners, small businesses. Dad didn’t help us. The fact that we were Daleys, everybody assumed that whatever walked in the door walked in [for that reason], and maybe it did. I don’t know. We didn’t ask, ‘Why are you here?’”

In 1974, the year before Daley graduated from law school, Joel Weisman, now moderator of WTTW-TV’s Chicago Tonight: The Week in Review and then working for the Chicago Sun-Times, reported that answers had been changed on the insurance broker’s exam that Daley had taken three years before. No evidence ever emerged that Bill had had anything to do with it. Ultimately, the man charged with altering the answers was convicted of perjury, but the conviction was later overturned. Supposedly his intention was to do a favor for the senate minority leader, Cecil Partee, who would then presumably score points with the mayor.

Daley passed the bar exam on the first try and started working for the family law firm, then called Daley, Riley and Daley. (Richard J. had been a partner, and his son Richard M., then a state senator, was one at the time.) Today, the firm is anchored by Michael Daley, the most private of the brothers, and by his current partner, John George. Daley and George remains a go-to place for zoning and tax appeals.

Bill Daley wanted more. In 1976, he became his father’s liaison to the Jimmy Carter campaign for President. Daley was hooked and, according to John, transformed—he lost the reticence that had characterized him since boyhood. By the late 1970s, Bill and Loretta had the heady experience of attending a White House state dinner. When in Washington, Daley would use Vice President Walter Mondale’s office. In 1979, Mondale invited Bill and Loretta to a dinner party at which they met Bill Clinton, then in his first term as the governor of Arkansas.

In 1980, Bill Daley ran his brother Richard’s successful race for Cook County state’s attorney. “Bill’s particular gift,” says Dawn Clark Netsch, who served in the state senate with Rich Daley, “is that he was not as impulsive as his brother is; he has a great capacity to be calm, to look ahead a little bit.” Bill was honing the pragmatism that came to define him, making alliances with the liberals who in 1972 had unseated his father from the Democratic nominating convention. In 1983, when Rich made his first run for mayor—facing the incumbent, Jane Byrne, and Congressman Harold Washington in the primary—Bill rejected any appeal to race. “One of the things Bill was quite adamant about was no . . . racial anything,” Netsch told a writer for The New Republic in 2000. She lent her progressive credentials to the Daley cause—he finished third—and recalls it as a “classy campaign.”

In the 1984 Presidential race, Walter Mondale’s campaign chairman, Jim Johnson, recruited Bill, who then traveled with Mondale every day from August until the election. Chuck Campion, a Mondale aide, says that Mondale tapped into Daley’s sense of “what regular voters think.” Mondale saw in him something rare: “In these campaigns, people get all excited and bummed out over everything,” Mondale recalls. “Bill Daley was our steadier. He just seemed to be able to keep it under control at all times.”

Mondale’s landslide loss to Ronald Reagan didn’t impede Daley’s trajectory. Robert Helman, who had recently become chairman of the Chicago law firm Mayer, Brown & Platt (now Mayer, Brown, Rowe & Maw), took a call from a former partner who was a friend of the Daleys: “‘Bill is thinking about what he will do,’” Helman says, remembering the conversation, “‘and is probably interested in talking to one of the leading law firms in Chicago, not necessarily yours.’” By December 1984, Daley had an offer of a partnership from Mayer, Brown and a way, says Alderman Edward Burke, “to leverage the relationships that he had developed.”

He was hired to help build the lobbying practice at the firm (euphemistically called “government relations”), although colleagues say that Daley’s potential didn’t involve his mayoral ties—his father was dead; his brother had yet to be elected mayor—but rather his close friendship with the House Committee on Ways and Means chairman, Dan Rostenkowski. “Bill did represent clients before Rostenkowski and other members of the Congress,” says John Schmidt, who later served as chief of staff to Rich Daley and is currently a partner at Mayer, Brown.

Wayne Whalen, who was a partner at the firm until 1984, says that his friend Bill Daley was “extremely good at looking at the list of Mayer, Brown clients and figuring out how his contacts could be helpful.” Helman calls Daley “a very quick study—you never have to tell him something twice—and a man of excellent judgment. Clients liked the idea they would have the benefit of his judgment.”

“Bill is obviously not a lawyer whose strength is in drafting complex documents and arguing nuanced cases in appellate courts,” says John Schmidt. “But the kind of work he was doing in representing companies that dealt with Rostenkowski requires a level of precision and intelligence. It’s rare—the ability to know the difference between a conference committee amendment that was going to sail through and one that was going to trigger a reaction from some representative.”

Before long, Bill Daley was moving at the top of Mayer, Brown’s practice, counseling boards of directors and chief executive officers. “Most of my partners have gone to the best schools,” says Tyrone Fahner, a former Illinois attorney general and the current chairman of Mayer, Brown, “but only a handful step back and give boards of directors strategic advice.”

In 1987, U.S. senator Joe Biden, a Delaware Democrat, decided that he wanted to be President and he wanted Bill Daley to help get him there. The prospects looked promising—the young senator seemed like “a star” and “could give a hell of a speech,” recalls Daley. Then a Michael Dukakis campaign aide leaked the news that Biden had lifted inspirational remarks about his supposedly hardscrabble childhood from a speech by the British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock. The charges, backed up by a videotape, came as the young senator, then the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, was running Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Judge Robert Bork. Convinced that Biden was “too unframed and undefined” to withstand the ridicule he was taking in the press, Daley advised his friend to quit the race and focus instead on derailing the Bork nomination. It was good advice. Biden became celebrated for denying Bork a seat on the high court. Mark Gitenstein, then the chief counsel to the Judiciary Committee, calls Daley the best crisis manager imaginable. “‘Grace under pressure’ is the best way to describe him.”

In 1989, when a special election was called to complete the term of the late Mayor Washington, the Sun-Times columnist Steve Neal reported that Bill was ready to run and had even hired a consultant. He dropped the plans when Rich made it clear that he wanted to assume their father’s office. After Rich’s election, Bill was elevated anyway; reporters began referring to him as the co-mayor—the implication being that the smoother, smarter younger brother was pulling the strings. Bill calls the suggestion “a joke” and insists today, “We don’t talk about city stuff. We talk about the Kerry race or personal stuff. But I don’t get into his business.”

Other observers began calling Bill the “smart Daley,” when what they meant was that he was the “articulate Daley.” As one reporter puts it, “His sentences have a beginning, middle, and end.”

Perhaps feeling a sting of sibling rivalry, Bill decided after his brother was elected mayor that he wanted to show he had the stuff to run a business. He took the job as the vice chairman, and later president, of the Amalgamated Bank, a Mayer, Brown client. Amalgamated, with its roots in the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers’ Union, was known as a bank hospitable to politicians and unions, and it has long carried, fairly or not, an air of unsavoriness. The bank’s chairman, Eugene Heytow, who did not respond to requests to be interviewed for this article, is considered to be a potent political player.

Daley had been at Amalgamated for two years when Bill Clinton stopped by his office and shared his plans to run for President. He needed the Daley family’s help—as it turned out, more than he could have imagined. The Gennifer Flowers scandal and draft dodging charges hit before the New Hampshire primary. Bill Daley was among the advisers who helped turn a potential disaster into a second-place finish in New Hampshire and make Clinton the “Comeback Kid.” With the Daleys’ help, Clinton won the Illinois primary. In the general election, Bill was the chairman of Clinton-Gore in Illinois. “He was very helpful in our efforts to win Illinois,” says Al Gore.

Daley was finding politics far more engaging than banking, and when Heytow rebuffed his second-in-command’s attempt to clarify the succession and to be given an ownership interest, Daley decided to leave. His friend Jim Johnson endorsed the idea. “I just believed from the beginning that he had the potential [to go to] senior levels of American government, business,” Johnson says. “I felt that [Amalgamated] was just much too small.”

Daley thought he had his next big job lined up. Both major Chicago newspapers reported that Clinton was poised to make Daley his Transportation Secretary; Daley’s daughter Maura called to tell him that he had the job—Tom Brokaw had said so on the evening news. (Daley says he called Brokaw to ask, “Tom, do you know something that I don’t know?”) One friend joked publicly that Daley already had a real-estate agent working for him in Washington. All that remained in December 1992 was the call from the President.

It never came. Transportation went to Federico Peña, the former mayor of Denver. Although there were rumors that Daley’s job at Amalgamated had raised red flags among the vetters, the standard story was that Clinton realized he needed a Hispanic Cabinet member if he was to keep his promise to make his administration look like America.

Today, Daley attributes the humiliating rejection to a “screwed-up” Clinton transition. “There are 14 Cabinet spots, and God only knows how many hundreds of people want them,” he says. “They needed a Hispanic.”

Rich Daley was furious and soon blasted Clinton for not keeping his promises to help big cities. Bill knew it was wiser to keep his anger to himself. He was “really a trouper,” says Tony Coelho, “and that’s why when another spot came open he was asked.”

President Clinton quickly invited Daley to Washington to play golf and to bestow on him a lovely consolation prize, a seat on the Fannie Mae board—Jim Johnson was then chairman—from which Daley profited handsomely: In addition to a salary and fees, he received stocks and stock options, a package that climbed in value to an estimated $215,000 to $500,000 by the time he left the board in 1997. Daley also successfully approached executives at the government-financed mortgage giant about sending some of its securities work to Mayer, Brown, where he had returned early in 1993 as a partner.

The return to LaSalle Street was brief. Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, whom Daley had first met on the Mondale campaign, called to ask, “If President Clinton asks you to lead the charge for NAFTA, will you say yes?” Organized labor opposed the trade agreement for fear that the United States would lose low-wage manufacturing jobs to Mexico. As Mickey Kantor, another friend from the Mondale campaign and then Clinton’s United States trade representative, points out, Daley was the perfect fit. “You needed someone who could work with Democrats particularly, because [they] were the biggest problem,” Kantor says. Daley’s friendship with Dan Rostenkowski, alone among the Democratic leadership in supporting the agreement, was also a plus. Still, even Rostenkowski thought NAFTA looked like a loser. “Why the hell you doing this for?” Rostenkowski asked Daley.

John Daley remembers asking his brother, “Does the President really like you?”

Daley attacked the project with his full organizational skills. He regularly gave Clinton lists of names of congressmen to call, each accompanied by information on their districts, notes on what their problems were, and how the Administration could help. “We would get back the sheets the next morning,” Daley recalls. “‘Talked to this senator, that senator, that congressman.’” The battle invigorated the President, and Daley finally had to tell him that he was calling too much. “People were like, ‘Tell him to stop calling, to stop inviting me down to the White House. Just leave me alone; get the focus off of me.’”

“They called me the czar,” Daley says, smiling at the memory.

They also called him the dealmaker. “We had it won until the last week and a half,” says David Bonior, who claims the Administration passed out some $20 billion in goodies for the districts of legislators on the fence. Don Rose, the Chicago writer and political strategist, says that Daley won NAFTA because of his “ability to find everybody’s price.”

For Daley, it was a heady time. He met with the President and Vice President every day. He joined in the White House staff meetings. Some outsiders suspected that Daley did not know what was in the treaties. Those who worked with him say he knew enough to be effective. “Bill was focused on the jugular,” says Sandy Berger, who joined the NAFTA team and was later Clinton’s national security adviser.

NAFTA passed in the House in mid-November 1993, and in the Senate soon after. Al Gore gives Daley “virtually 100 percent of the credit. Nobody thought that we could get [NAFTA], but he was able to pull it out of the bag.”

That victory, says John Daley, was “the time he proved himself on his own.” Bill, who had taken a leave of absence from Mayer, Brown, returned in triumph—but, as always, with the question “What’s next?” on his mind.

Back in Chicago, Daley helped organize the hugely successful 1996 Democratic National Convention. That December, after Clinton’s re-election, Daley was having dinner in Washington when he got a call from Gore.

“You’re going to get a call a little later,” Gore said.

Daley, who preferred the Commerce Department to Transportation, asked, “Am I going to be wearing a railroad hat or a banker’s suit, Al?”

“I think you’ll be pleased,” the Vice President responded.

Daley returned to his hotel, where President Clinton called at around 10:30 to offer Commerce.

The next morning, during a nationally televised news conference in the Old Executive Office Building, Clinton introduced his nominees for Cabinet departments. The room was hot, and the bright lights made it hotter, as did the crush of journalists and television cameras. Daley started sweating, turned pale, and soon toppled headfirst from the stage into the lap of CNN newsman Wolf Blitzer. Daley’s son, Bill, who was in the audience, ran backstage, fearing his father had suffered a heart attack. A White House doctor dispensed apple juice, checked his vital signs, and determined nothing was wrong. Bill called relatives in Chicago who were watching the proceedings on television to report that everything was fine. Ten minutes later, the embarrassed nominee was applauded as he returned to the stage.

Today, he attributes the episode to a combination of having lost a lot of weight—he had wanted to look trim at the convention the summer before—and staying up most of the previous night, “calling people and with [political strategist] David Axelrod and others trying to figure out what I would say. And the next day I didn’t eat; I was nervous.”

The confirmation hearing itself seemed daunting. Buried in thick briefing books, Daley agonized that the hearings would be a quiz on what he knew about a department with 45,000 employees that encompassed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Weather Service, the Patent and Trademark Office, the Census Bureau, and much more. “I couldn’t sleep, not just the night before but lots of nights around it.”

Senator John McCain, a friend and the chairman of the Commerce Committee, gave him some advice: “Quit approaching this like the bar exam. We want to know who you are, not what you know.” Daley recalls being told repeatedly that the senators don’t care what the nominee’s answers are. They just want to hear their questions.

“There is no room for politics in the Commerce Department,” Daley declared at thetop of the hearing, and he sailed through to confirmation.

As if to prove he was no lightweight, Daley worked 14-hour days; he was up at five and at the gym before arriving at his office at 6:30. He focused on the operational side of things, says Linda Bilmes, whom he brought in as his assistant secretary for administration and chief financial officer—taking on vested interests, shaking the place up by forcing senior career people to switch jobs, insisting on accountability, and cleaning up the balance sheets, which were such a mess that they had been declared “unauditable.” Bilmes describes Daley’s greatest strength as “cutting through the bullshit in Washington.” She thinks it helped that he came from Chicago and was “not beholden to the Beltway scene.”

By one standard, Daley’s tenure at Commerce was successful—calls for its abolition ceased. “I think he’ll be remembered as one of the best and most effective Secretaries of Commerce ever,” says Al Gore.

As Commerce Secretary, Daley went to almost all the state dinners and accompanied the President on most international trips. Having a front-row seat for the Monica Lewinsky scandal was less entertaining. When the story first broke, Bilmes says, Daley called his top people at Commerce into a meeting and warned, “We are here to do a job. If anyone should feel any wobbliness whatsoever, I want your resignation.” He was one of the Cabinet members dispatched by White House aides to face reporters and to express his total faith in the President. Eight months later, after admitting that he had lied, Clinton convened his Cabinet to apologize. Daley was alone in skipping the meeting, keeping his commitment to give a speech in New Hampshire. “My attitude was, Why are we torturing this poor guy?” Daley explains today. The journalist Roger Simon later reported that Daley told the President’s chief of staff, “Look, I’m glad I didn’t go. I don’t quote scripture, I don’t cry, I don’t hug. What would I have done at this thing?”

Bill Daley could commiserate with the President; Daley, too, was having problems in his marriage. Loretta might have preferred that her husband remain in the family law firm. While Bill was on and off airplanes, she was having children—first William R., then Lauren, Richard J. Daley II, and Maura.

Richie, as the second boy was called, seemed normal as a toddler, but turned out to suffer from chronic fibrosis of the lungs. The Daleys took him to specialists all over the country, but the boy kept getting worse. By second grade, he was hooked up to an oxygen machine in his classroom and soon he needed oxygen 24 hours a day. He died at age eight in March 1985.

Bill Daley’s desk at Commerce was almost completely clean, except for a group photograph of his children and a separate photograph of Richie. Today, Bill remembers Richie as having “a great personality for a little kid. He was a very perceptive young person with a great sense of humor. He kept that through some very, very difficult periods.”

In the last year of Richie’s life, Bill was often traveling with Mondale. When the former Vice President’s plane stopped in Chicago, Bill made sure that Richie got to meet Mondale and have his picture taken.

In 1995, Daley considered running for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Paul Simon, but eventually decided against it, telling Steve Neal, “My family doesn’t want to move to Washington, D.C.” Neal, a friend of Daley’s, wrote, “Political ambitions are less important to Daley than his family.”

Yet a year later, when he accepted the Commerce job, he did so, friends say, without Loretta’s blessing. She sat behind him during his confirmation hearings, looking unhappy and frightened. Her son, Bill, chalks that up to nerves. “We were all nervous,” he says.

Loretta had little interest in politics, says one friend. She maintained an air of independence and was intensely focused on rearing her children. For a while, the friend adds, the couple told others that Loretta would join her husband in Washington as soon as Maura graduated from St. Ignatius. But Maura went off to college and Loretta stayed in Chicago.

Today, Bill Daley declines to talk about his marriage. (Loretta Daley did not respond to a request for an interview.) “Just what’s reported is accurate,” Daley says. And that’s not much. In March 2001, the columnist Michael Sneed wrote in the Sun-Times that the couple had separated, and she proceeded to speculate: “Rumor: The couple’s marriage was on the rocks before Daley’s acceptance of a Cabinet position, but they appeared to patch things up when Mrs. Daley occasionally traveled to Washington to attend state functions. But word spread Mrs. Daley was unhappy with her husband’s decision to accept the job in the first place.”

Friends, colleagues, and family seem uncomfortable, almost scripted, when discussing Loretta. “She’s a great friend,” says John Daley, “a great woman. She’s a lovely, beautiful girl; a wonderful mother.”

During his confirmation hearings, the Daleys’ Tudor-style house in Sauganash was burglarized. Loretta, frightened to remain in the house that one friend describes as so grand that it looks as if it were out of a Chivas Regal ad, moved to Lincoln Park with her daughters. When in Chicago, Bill stayed at the Four Seasons and later bought an apartment on North Lake Shore Drive. In the Cook County courts, there is no record of a legal separation or divorce.

In June 2000, Daley was in his office at the Commerce Department when his chief of staff, David Lane, who was rushing off to meet out-of-town friends, caught his boss gazing pensively out the window. “You can’t have dinner?” asked Daley, who lived alone in a condominium on Pennsylvania Avenue. He sounded so plaintive that Lane put aside his plans. “I feel it coming,” Daley told him that night. Daley knew he was going to be asked to head the struggling Gore campaign.

“Commerce was the best job I could ever have,” Daley says today. For the first time, he had not been thinking about what he would do next.

A believer in his father’s admonition “Nothing good ever happens after midnight,” Daley was asleep that night when Al Gore called. “Let’s talk over coffee,” the groggy Commerce Secretary told the Vice President. “I was trying to stall,” Daley later recalled. “I’ll wait while you make a pot,” Gore replied. Daley had turned down the job a year earlier—it went to Tony Coelho, a former congressman—and he knew that loyalty meant he could not say no again. The official word was that Coelho was resigning for reasons of ill health. He was indeed ill, but so was the campaign, down 25 points in the polls. “Gore was in trouble,” Daley says. “Everybody was beating him up. It just didn’t seem right to say no when a lot of people were saying no to him.”

Daley’s job was to be the adult in the campaign, to discipline an unruly staff, “to keep the ships running on time,” as Gore’s campaign manager, Donna Brazile, puts it. Tom Nides, who ran Senator Joseph Lieberman’s Vice Presidential campaign, said that Daley was “the only one who could stand up to Gore. Bill was a peer; he had been a Cabinet secretary.”

Daley left his wood-paneled Commerce office, with its views of the Washington Monument, for a space in a strip mall in Nashville. Daley joked that he had an office that “looked out onto license plates.” He lived in a room in the Loews Vanderbilt Hotel.

Gore was trying out earth-tone casuals, but Daley stuck to a suit and tie. He was “always well dressed, well prepared, and very much in control,” says Brazile. Daley ran the campaign “like a board meeting,” she adds.

“I have enormous respect for his political skills and judgment, but I tend to lean toward the individuals like the Tony Coelhos who are involved and more engaged in rough-and-tumble politics as opposed to what I call executive politics.”

Explaining his style, Daley says, “It’s not just the politics part. But you’re also conveying in everything you do that you could run the government of the United States.”

The screaming matches born of too much caffeine and too little sleep ceased. “You don’t scream at Bill Daley,” Nides says. “You don’t have temper tantrums. People knew that when Bill said no, it was no.”

Daley needed all his cool on November 7, 2000, a rainy election night, when he went to the Vice President’s suite at the Loews in Nashville and told him that it was time to concede. The networks had just put Florida in the George W. Bush column. The Texas governor was ahead by 55,000 votes, with less than 1 percent of the vote uncounted.

But as the Gore motorcade pulled away for the six-minute ride to the War Memorial Plaza, where the Democratic candidate would make his concession speech, Daley’s phone rang. “Bill, did you know that [Bush’s lead over Gore] slipped to 10,000?” asked the Newsweek correspondent Howard Fineman. Daley remembers that the call left him with “a sick feeling in [his] stomach.” Others were buoyed by the hope that tragedy could morph into victory, but Bill Daley was rattled by the chaos he knew would ensue.

Suddenly barraged by updated numbers from his troops manning the “boiler room,” Daley rushed to the basement of the War Memorial, where Gore and Lieberman had stopped en route to taking the walk to concede. “Our understanding is that the official tally in Florida has dropped below 2,000,” he told Gore. “We’ve got an issue; we’ve got to check it out.” At 2:30 that morning, with the world watching, Daley walked out in the rain at the plaza to tell Gore supporters, “Our campaign continues.”

“I felt real bad because I felt I had kind of encouraged the concession,” Daley later told Roger Simon. One person near the top of the Gore campaign who was trying desperately to put the brakes on the concession train says that Daley was right to feel bad—that he was too quick “to throw in the towel.”

Although Daley made some trips to Florida during the recount fight, mostly he stayed in Washington, spending part of every day at the Vice President’s house. He calls the experience “pretty depressing.” He had to run the gauntlet of Bush-Cheney backers on his way in and out. “One of the groups was [evangelical],” he recalls. “As I’d drive in, the nastiness, the anger in these people, really it was over the top. This was the Vice President of the United States. You may not agree with his policies, but there was a meanness to it, that chant, ‘Get out of Cheney’s house!’ It was just really almost frightening.”

The scene inside, Daley says, was “kind of a Fellini movie”—meals with the Gores and their children, TVs blaring, phones ringing, trying to figure out “what was actually happening.” Ultimately, the United States Supreme Court voted five to four to stop the recount, giving Bush Florida’s 25 electoral votes and thus the White House.

When asked if he thinks he would have won the election if Daley had joined the campaign earlier, Gore says, “Yes, I do.” How much earlier? “Given the closeness of the outcome in Florida, maybe a week earlier.”

Not everyone agreed. Many have said the campaign should have used Bill Clinton more. Daley has heard the complaint so often that it strains his cool; he insists that the decisions on Clinton were “perfectly handled.” The states in which Clinton was popular were already in the Gore column, he explains, and in the red states, Clinton would have cost Gore votes. Brazile disagrees, arguing that Clinton could have helped get out the black vote in Gore’s home state of Tennessee and Clinton’s Arkansas. Either in the Gore column could have put him in the White House.

Daley will admit to only one miscalculation: his nonstrategy on Ralph Nader. “We gave him a pass,” Daley says. He did not believe that voters would “throw away” their vote. Nader’s 97,488 votes in Florida cost Gore the state.

Returning to Chicago and a troubled marriage did not seem to be the right next move. Roger Altman, the deputy Treasury Secretary during Clinton’s first term, suggested that Daley join Evercore Partners, a New York–based investment banking firm that Altman was forming. Austin Beutner, who became Evercore’s president, says that Daley was brought on because he was “likable, honest” and could help clients think through complex problems that sometimes involved regulated parts of their businesses. “I’m not sure that Bill is the first guy [I’d] ask to help me in a derivative mathematical calculation,” Beutner says.

Living alone in a rented apartment across the street from the United Nations Plaza was lonely, Daley’s friends say. “New York’s a tough place,” says one colleague. “You go there thinking that you’re a major figure in the world, and all of a sudden you’re one of however many investment bankers, and they’re all hustling for deals.”

After September 11, 2001, raising money and living in Manhattan became much more difficult. Daley stayed at Evercore until a better offer materialized that November—to become the president of SBC. By December 1st, Daley had moved from New York to San Antonio. Ed Whitacre, the chairman of the highly regulated telecommunications company, was having trouble making his case to officials. He hired Daley, fancy title and job description aside, to lobby, to “grease the skids with regulators and politicians,” in the words of one reporter who covers the industry. (SBC is regulated in 13 states and also by the Federal Communications Commission in Washington.) Daley’s Midwest clout, particularly in Illinois, a key market for SBC, magnified his value to the company. He could also schmooze Democrats. SBC gave generously to George W. Bush and his party. “They wanted him because he was a Democrat,” says Brian Moir, a telecommunications attorney in Washington. He was certainly not hired for his telecommunications experience, which was negligible.

Daley made plenty—a $1.1-million signing bonus, $612,000 in salary, 90,000 nonqualified stock options, and an $890,000 bonus that first year—a total of about $2.7 million. The pot grew richer every year.

As he had at Commerce, Daley plunged in to master the business. Whitacre calls Daley “really a quick learner.” One reporter who interviewed Daley remembers, “He knew a lot about what they needed regulation-wise, but when it came down to the nuts and bolts of the telecom business, he would say, ‘That’s not my bailiwick.’”

Neither was San Antonio. “There was no question I wasn’t the happiest person in San Antonio,” Daley says. David Lane recalls asking his former boss how he liked Texas. “[SBC] had a good airplane,” Daley replied.

He was on that plane often, sometimes with his friend Roger J. Kiley Jr.—a Mayer, Brown partner and a former chief of staff for Mayor Richard M. Daley—who, at Bill’s recommendation, had become SBC’s Midwest general counsel. They went to Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, and Illinois—at each stop meeting with the governor and key legislators and with regulators, as well. Daley followed the same drill for SBC states in the West and the Southwest. Under Daley’s watch, the company won government approval to sell long-distance service in the five Midwest states in which it operated.

In May 2003, Daley seemed to have won his most audacious victory. After four days of manic lobbying, the Illinois General Assembly passed a bill hugely favorable to SBC. Negating a decision by the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC), the legislation allowed SBC to more than double the fees charged to competitors using its local network. Within hours, Governor Rod Blagojevich signed the bill. U.S. representative John Conyers of Michigan called it “a national embarrassment. The Democratic Party is supposed to stand for consumers.”

A month later, when a federal judge ruled that the law was anticompetitive and contrary to federal statute, Daley’s victory turned into a crushing defeat. His strategy of bypassing the ICC, which regulates telecommunications companies, and appealing directly to the legislators could not pass judicial muster. For all Daley’s classy associations, he looked like a machine hack hawking Chicago-style clout politics. “He couldn’t deliver on the one thing they wanted,” says a former law partner. Whitacre says he does not count it as a failure of Bill Daley’s tenure as SBC president. “We were all in uncharted waters here,” he explains.

Less than a year later, Daley announced he was leaving. Jim Rogers, who at the time was writing a newsletter on the industry, says that SBC did not mind Daley’s departure because he had accomplished what he was hired to do, despite the defeat in Illinois. “They hired him to win the hearts and minds of regulators in the Midwest. For all intents and purposes he succeeded.”

Daley says he might have stayed at SBC if he had had a shot at being named chief executive officer. But he knew that Whitacre, 63, wasn’t going anywhere; when he did, his chief operations officer appeared to be the likely successor. Typically, Daley already had another offer in hand. “There’s not another situation like this in Chicago that would have gotten me back,” he says.

Ed Whitacre announced Daley’s departure from SBC on Friday, May 14, 2004. The following Monday, Daley announced that he was joining J. P. Morgan Chase, which was about to acquire Chicago’s Bank One. The newly merged banks, headquartered in New York, would be second in size nationally only to Citigroup.

Like Ed Whitacre, Jamie Dimon met Bill Daley while he was the Secretary of Commerce. Dimon had been the chairman of Bank One, but with the purchase, he had moved up to president and chief operations officer of J. P. Morgan Chase. Dimon says that he and William B. Harrison, the chairman of the bank, made a list of names for the new position of Midwest chairman and “one person was always at the top of it.” The frequency with which Daley’s name was suggested by business leaders “almost shocked me,” Dimon says. “We didn’t think we’d have a chance.”

Some say it is a figurehead job, with a focus on dispensing philanthropic contributions and courting big customers at expense-account restaurants—a kind of goodwill ambassadorship. After all, despite mergers and name changes, the bank was a Chicago institution, and now it was moving, along with Dimon, to New York. But Dimon insists that the Midwest is a crucial part of the bank’s market. “Anybody who thinks that [Daley is a figurehead] doesn’t know me at all. That would be a waste of money, and I don’t waste money.” Daley is the senior corporate officer in the Midwest, Dimon says, and he holds a seat on the executive committee, which will put him in touch with all parts of the company and its people in the United States and abroad. “Bill has to earn his way, more than earn his way,” insists Dimon. The Chicago lawyer Wayne Whalen guesses that Daley will be expected to help the bank compete for business. “If they want Berkshire Hathaway business,” he says, “Bill can call Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger and talk to them.”

“Clearly he decides who gets the charitable contributions in Chicago,” says a former colleague of Daley’s, “but if that’s all it is, I don’t think that’s going to satisfy him.” (Daley’s first official act was to announce the bank’s underwriting of the cost of the opening celebrations for Millennium Park, whose biggest booster was Mayor Daley.)

How big an attraction for Dimon and company was Bill’s big brother? “He’s not working on the Chicago business,” says Dimon. Jim Crown, the president of Henry Crown and Company, who describes himself as the last remaining Chicagoan on the merged bank’s board, says that Daley’s Cabinet experience made him an attractive prospect. “Mayor Daley is not going to have an impact on the governor of the Federal Reserve and the Comptroller of the Currency,” Crown says. “At the bank we care most earnestly about what’s going on in D.C.”

Sitting in his bank office before the election went Bush’s way, Bill Daley mused about possible jobs in a Kerry Administration: “Treasury would be interesting. UN ambassadorship would be interesting.” Today, his friend Jim Johnson says, Daley is “very clearly committed to his new position at J. P. Morgan and does not intend to return to government service.”

Daley certainly has deep reservations about elective office. When Joe Biden briefly considered a run for President in 2004, he talked to Daley, who recalls telling the Delaware senator, “You have to be almost sick to do this stuff at a Presidential level. I don’t know if you’re sick enough, Joe. Are you really willing to put everything aside, your personal life, your family? If you have to run to Iowa for a birthday party for somebody, you’ll do that before you go to your daughter’s birthday party.”

Bill Daley is especially close to his son, Bill, 32, who has worked in several Presidential campaigns, including Kerry’s. In 2002, Bill became a lobbyist in Washington for Fannie Mae, on whose board his father had once sat. The following year, he completed his MBA at Northwestern University. The younger Daley and his wife are expecting their first child, Bill and Loretta’s first grandchild, in March. Their daughters, Lauren and Maura, are both teachers—Lauren is currently teaching sixth grade; Maura has taught kindergarten. Their father says that neither has an interest in politics. “They like their privacy,” he says. “Billy is a lot more outgoing.”

These days, the Mayer, Brown partner Roger Kiley says he sometimes gets an early-morning call from Daley: “‘Hey, you want to go over and get some lard for breakfast?’ and so we go over and get eggs and bacon and grease and butter.” They often walk and end up in a bookstore. Asked what he was reading in late August, Daley named several books, among them former Commerce Secretary Peter G. Peterson’s Running on Empty, which warns that both political parties are “bankrupting our future,” and Ward Just’s latest novel, An Unfinished Season, set in Chicago. Bill Clinton sent an autographed copy of his memoir—as of last summer, it was well positioned on Daley’s office shelf but unopened. At night Daley is often seen at his favorite restaurant, the Rosebud steak house on Walton, sometimes with his brother John, who was the closest to him when they were growing up and remains the closest today. Bill Daley still spends weekends in Grand Beach, where he and Loretta have a house, and sometimes has dinner there with his pal Rahm Emanuel, the congressman, who has a house nearby.

His friends bristle at the notion that Daley got where he is because of his name. “You could be handed a lot of silver spoons,” says Tom Nides, his colleague from the Gore campaign. “You could be handed a great name; you could be handed a lot of money, a lot of power. It’s what you do with the money, the power, and the fame that is important. If you look at Bill’s life, he has been able to exceed every expectation.”

Bill Daley’s portrait now hangs with those of other Commerce secretaries on the wall outside the secretary’s office. Daley says that his portrait is a little different from those of his predecessors: “It’s not a totally finished portrait—it’s still a life in progress.”