As a member of the Fenwick High School swim team, Larry Wert excelled at diving. Today the trim 51-year-old general manager of WMAQ-Channel 5 still makes the occasional leap, although it’s tougher than it used to be. During an interview, Wert rolls up a pants leg to reveal a scary-looking—but not very serious—gash along his shin. “I was showing off to my kids,” Wert says of his recent attempt to land a flawless one-meter inward pike. “My head said I could but my body said I couldn’t.”

These days, Wert and his fellow local TV station managers are taking another type of plunge—a risky free fall into the high-tech digital age. As traditional local TV viewing declines and the remaining audience taps into whiz-bang devices ranging from giant viewing screens to tiny iPods to watch area news, sports, weather, and other programs, Chicago’s TV outlets are scrambling to stay connected with viewers. The stations are investing heavily in an array of new products and services, including high-definition broadcasting equipment, more on-demand programming, and a slew of Internet-based news, information, and social networking sites. And that’s just the beginning. “These are seismic changes,” says Wert. “You can’t stay ahead of them…. You hope to keep pace.”

Nobody knows if the new strategy will save the day or even make money for the stations, but standing still is not an option. If the city’s local TV outlets—mainly those owned and operated by the Big Four networks as well as Tribune Company’s WGN-TV—don’t successfully adapt, they risk suffering the same fate as newspaper companies, which were slow to change and are now reeling from loss of audience, serious earnings declines, massive cost cutting, and industry-wide contraction.

“The number one topic of conversation at the stations is, Will we be around in ten years?” says Bill Kurtis, former WBBM-Channel 2 anchorman and now a media industry entrepreneur.

* * *

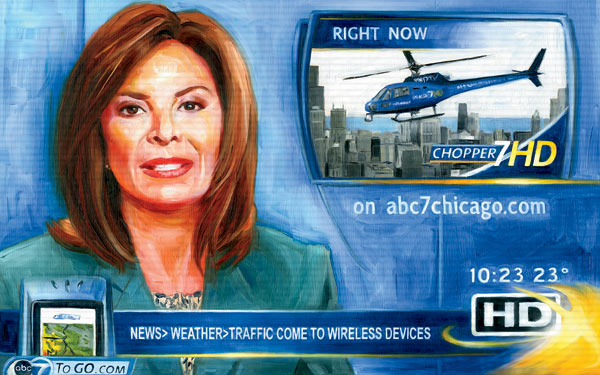

Illustration: Robert Carter/CrackedHat.com

This is not the first time local TV stations have been forced to reinvent themselves. During the 1960s, color television displaced the old black-and-white sets; later, cable and satellite TV services emerged to rattle the status quo. But this time, fighting back may be tougher. The audience has an unprecedented number of viewing options, and local TV is just one of many. As a result, the number of people tuning in to original local TV programming—which consists primarily of morning, evening, and nighttime newscasts—has been “decreasing sharply,” according to the latest study by the Project for Excellence in Journalism, which evaluates the press as an affiliate of the Washington, D.C.-based Pew Research Group.

Reporting on national averages, the study found that in the November 2006 ratings “sweeps period” (when advertising rates are determined), morning news ratings were down 6.7 percent from the same period the year before, while evening news was off 2.8 percent and late news (at 10 p.m. in Chicago) was down 6.3 percent. That recent slide is merely the continuation of a trend that began years ago.

The national results closely mirror trends in the Chicago market. In May 1988, for example, approximately 1.3 million Chicago-area households were tuning in each night to the 10 p.m. newscasts of Chicago’s three network affiliates (WBBM, WLS, and WMAQ), according to an analysis of Nielsen data from that period. Nowadays there is a fourth ten-o’clock local newscast, that of Fox-Channel 32. Last May, the four stations’ combined viewership for the ten-o’clock news came to 799,000 households—a 38-percent decline from the May 1988 total.

Local station managers are hoping the introduction of high-definition (HD), a signal that provides a clearer, sharper, and brighter picture than the present analog technology, will reignite interest in local TV fare. Under federal law, all stations must start broadcasting in an all-digital format by February 17, 2009, and the majority of those will beam in HD. (Right now, many stations are broadcasting digital and analog signals.) Stations across the country, including those in Chicago, are spending millions of dollars to make the conversion.

The marketplace is also gearing up for HD’s mass debut (cable and satellite TV companies are currently providing some HD programming to subscribers, though it can be seen only by those with HDTV sets or digital converters attached to their analog sets). In October, the electronics retailer Best Buy announced it would no longer sell analog television sets, only digital video tuners. Other retailers are expected to follow, say broadcasting executives.

There’s a lot of pent-up consumer demand for HD, and sales are expected to mushroom between now and the mandated deadline. Currently, only 14 percent of Chicago-area households own an HD television, which lags the estimated 17 percent in New York and Los Angeles but is higher than the national penetration of 11.3 percent, according to the New York-based A. C. Nielsen Company, which tracks ratings and audience numbers.

Moreover, giant 100-inch flat screens—which often sit at the center of “home theatre” surround-sound systems—are increasingly popular with viewers making the switch to HD sets from analog. “HD is the biggest elephant in the room for the local stations and the consumers, who are being forced to deal with it,” says Lisa Pecot-Hebert, assistant professor at DePaul University’s College of Communication.

Some local stations are already beaming in HD. WGN-Channel 9 has been broadcasting Chicago Cubs, White Sox, and Bulls home games in HD since 2004 and intends to include the teams’ away games starting with the 2008 baseball season, says Tom Ehlmann, WGN-TV’s general manager. (Watching sports programming is definitely an incentive for early HD users. Nielsen reports that 42.8 percent of viewers nationally with HD sets at home are using them primarily to watch sports.)

In addition, WLS-Channel 7 boasts that it’s the first local station to broadcast its news programming in high-definition and has integrated the “HD” symbol into its marketing and publicity efforts, even claiming it is “Chicago’s HD station.” Meanwhile, other stations are getting ready for their HDTV close-ups. WBBM-Channel 2’s new street-level studio, scheduled to open in 2008 in the heart of the Loop, is being fitted out with new cameras, a high-tech sound system, and lighting that will produce a broadcast “light-years ahead” of the old analog system, boasts Joseph Ahern, the station’s general manager.

Aside from the quality of the HD picture itself, perhaps the biggest change viewers will notice is a proliferation of smaller channels. Because of the more advanced digital signal, which occupies less bandwidth than analog signals, traditional TV outlets could spawn up to six stations under their banner. Already, area cable subscribers will notice some familiar names as they scan the dial. WLS-TV has two smaller channels. Channel 7.3 is an all weather and news-bulletin station, while 7.2 airs reruns of local programming and commercials. (WMAQ also has two digital stations with similar philosophies regarding content.) Right now, these stations are placeholders until a better use can be determined, station managers say. “They’re watched by a very small sliver of people,” says Emily Barr, Channel 7’s general manager. “But they present some interesting opportunities for us.”

One digital station has already tested and abandoned a new format: WGN-TV experimented by running nonstop music videos on one of its digital channels (WGN-DT), but that syndicated program, marketed as The Tube, went down the tubes earlier this year because it lacked viewers and sponsors. Also, cable companies didn’t want to pay a fee to carry The Tube, says WGN’s Ehlmann.

Yet, despite the slow start, industry experts suggest that showcasing a junior varsity of local stations may pay off. Depending on the content, the stations could become premium channels that cable companies, or subscribers, paid an extra fee to receive, which could provide local TV stations a new revenue stream, says Pecot-Hebert, of DePaul.

* * *

While the HD revolution is fast approaching, some other major technological uprisings are already under way, including the growing popularity of the digital video recorder (DVR) and the pervasive use of the Internet for providing local news and information. The DVR is rapidly replacing the videocassette recorder (VCR), and every day new and improved digital recorders come to market, the best-known brand being TiVo. Unlike a VCR, which can hold a few hours of content on tape, a DVR can record more than 100 hours of programming, which, depending on the system being used, can then be played back on a TV monitor, computer, or personal entertainment device such as an iPod.

As basic DVRs become more affordable (a TiVo HD DVR retails for about $300), they’re rapidly losing status as a cool electronic toy and turning into just another household appliance. In May 2007, an estimated 20.5 percent of the households participating in Nielsen ratings surveys had DVRs, compared with 8 percent in January 2006, according to Nielsen. “First there was the toaster, then the VCR, and soon the digital video recorder,” says Channel 5’s Wert.

In addition to ample recording capacity, DVRs give users greater control over how and when they view shows—hours, days, or weeks after their original airtime. Right now the majority of DVR use is aimed at sporting events or regular network prime-time shows, such as NBC’s Heroes or ABC’s Grey’s Anatomy. That viewing trend is so commonplace that Nielsen’s clients, among them major advertisers and TV stations, are pressing to learn the total audience for a show for up to seven days after broadcast—a combined measure known in industry parlance as ‘live plus seven.’ “Clients are telling us to follow the video,” says Anne Elliot, a spokeswoman for Nielsen.

Local station managers note that DVRs will be playing a larger role in determining what they can charge advertisers for content, whether it’s their newscasts or other locally generated sports or entertainment programming. They’re ramping up to sell those metrics to clients, but that may be difficult given that one of the DVR’s main perks is the ability to zap past whole blocks of content, including commercials. “Lots of the ratings occur nonlive,” says Wert. “Do we think that has value to an advertiser? We think, yes.”

Other experts note that many big advertisers don’t know how to evaluate this new ratings system yet. “Advertising? It’s kind of a mess. They’re putting a lot of pressure on the stations, but [advertisers] don’t know what to do,” says Limor Peer, research director at Northwestern University’s Media Management Center.

* * *

While trying to determine the value of delayed responses to their programming, local TV stations are also dealing with the real-time demands of the Internet era. All of Chicago’s network owned-and-operated stations and Tribune Company’s WGN-TV have upgraded the design and content of their Web sites in recent years. These sites serve primarily as marketing vehicles that bolster a local station’s brand name, showcase its network shows, act as “portals” to other Web sites, and dish out regular helpings of news, weather, sports, and other information.

Now, to keep pace with the public’s appetite for more Web-based access, they’re providing a growing assortment of customized Internet products and content. Click on Chicago’s TV station sites and you’ll see a glut of Web-based come-ons, including podcasts of restaurant reviews, text-based sports and weather alerts for cell phones, and blogs penned by the station’s star reporters.

As the digital capabilities improve, stations will transmit more video alerts and other information to individuals’ cell phones, computers, and other mobile devices, general managers contend.

Some stations are also getting really local. Channel 32’s Web site highlights local high-school football games with videos shot by family or friends and then posted on the site. “We’ve got to build out channels to niche audiences,” says Patrick Mullen, general manager at Channel 32. “Our belief is high-school sports are underreported.”

Others are coining their own original Internet programming. Channel 2 has used its Web site to stream breaking news events, and Channel 7 offers a daily Web brief, anchored by Alan Krashesky, produced exclusively for its site.

That’s just the beginning. Every local station is being forced to determine new and different ways of using its Web site, especially in covering local news. More than ever, local TV Web sites are becoming important vehicles for breaking news or for advancing ongoing stories. In the bygone era of TV journalism, newsrooms could break into regularly scheduled programming with “bulletins” reporting a major accident or event. Now it’s just as likely that a station will maintain its regular programming and flag the breaking news with an electronic “crawl” at the bottom of the screen, which directs viewers to the Web for details. In the future, viewers may also be regularly referred to one of the station’s smaller digital channels, too.

* * *

These new delivery systems are igniting some interesting discussions between newsroom and station management, which basically asks, How big does a story have to be before we break into regularly scheduled programming? Veteran newsman Kurtis says local news is being categorized into “different grades of stories.” He adds, “If the mayor has a heart attack or a jumbo jet goes down, you break into regularly scheduled programming. Lesser stories get treated differently.” Says WLS’s Barr, “We’re very aware, particularly with soap operas, of a very loyal audience that really resents interruptions.”

TV executives are also aware that they’re still highly dependent on the profits generated by their mainstream, old-line programming. Money from that part of the business is used to pay for ongoing operations and to help cover investment bets on new technology. “Traditional TV is now one part of a local station manager’s business,” says Paula Hambrick, a locally based media buyer. “The Web is huge; digital channels are on the way. They’re playing with them right now, but at some point you have to monetize it.”

Station managers would love nothing better than to turn a quick buck on these new bells and whistles, and they contend progress is being made. All five general managers interviewed for this story say their Web sites, which all carry some advertising, are turning a small profit. None would say how much.

“The revenue models can’t be based on selling 30-second [commercial] spots, although they are not going to go away very soon,” says Channel 5’s Wert.

Although TV stations are known for crying poor, they still make a ton of money. The latest survey of the industry’s profitability by Journalism.org, an affiliate of Pew, estimated that average profitability for TV stations was in the neighborhood of 40 percent. Local general managers won’t reveal their stations’ returns, but they’re well aware that the newspaper industry’s average profit margin has declined precipitously—from 22.3 percent in 2002 to 16 percent in the first half of 2007, according to data cited in American Journalism Review—and they wish to avoid a similar fate.

* * *

With the number of local TV viewers dipping and the area’s traditional TV advertising market flattening in recent years at about $1 billion annually, station managers are squeezing their budgets like never before to maintain profits and keep their bosses happy, or at least at bay. That means getting more from existing resources while pressing personnel to shoulder much of the new technological expansion, especially getting current staffers to do more work on the stations’ Internet sites.

Even that approach may not be enough to stop periodic cost reductions, such as the cutbacks under way at the NBC network and its local stations, which are owned by the conglomerate General Electric. NBC is dumping about 700 jobs—nearly 5 percent of its work force—and slashing expenses by $750 million. (A spokeswoman at Channel 5 said the station hoped to avoid job cuts, opting instead not to fill positions that open through employee attrition; she declined to reveal how many people the station now employed compared with a year ago.) At Channel 2, Ahern’s longtime second in command, Fran Preston, was dismissed recently, reportedly to reduce costs. (Preston declined to comment.)

Such belt-tightening may also mean that some well-paid, well-known local anchors are on the bubble. “As a businessman, I would eliminate all the million-dollar anchors. I think that’s a big change,” says Kurtis, who made a good buck when he fronted for Channel 2’s news operation during the 1970s and 1980s.

Despite the uncertainty, local stations feel pressed to take the plunge into this new information age. “Some people embrace change; others are averse to it,” says Wert, that veteran high diver. “This is not a good time for the latter.”