Henrici’s, circa 1914, located at 71 West Randolph Street

Related:

PHOTO GALLERY »

Pictures from Lost Chicago and David Lowe's own private collection

Decades earlier, before it began its sad, slow slide toward oblivion, the big brick barn on 23rd Street reeked of glamour, culture, and an envy-inducing exclusivity. Situated just east of ultrafashionable Prairie Avenue, the building—a jumble of Queen Anne and Romanesque Revival styles—had been completed in 1883 from a design by John Root and Daniel Burnham, though clearly before those great architects had hit their revolutionary stride. Their client was Augustus Bournique, a dapper dance teacher who, with his wife, Elizabeth, instructed several generations of Chicago’s elite, among them the Pullmans and the Fields.

But with the advent of a new century, all that glitter had gravitated to the city’s North Side. Abandoned by the Bourniques, the remodeled building became a trucking company’s garage that then gave way to a cavernous brauhaus called Sauer’s. In a few more years, the place would vanish entirely. In other words, it was perfect.

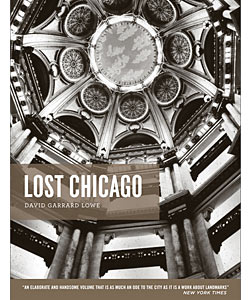

Perfect, that is, if, on a December night in 1975, you were searching for the ideal setting to celebrate the appearance of a book dedicated to the city’s glorious but rapidly disappearing past. A boyish-looking magazine editor named David Lowe had proposed to a New York publisher a collection of essays and photographs cataloging the Windy City’s many destroyed architectural treasures. The publisher, Houghton Mifflin, had agreed to a small run of about 1,000 copies. No one expected the book to generate much interest—even among the residents of Chicago.

Then a funny thing happened. Paul Gapp, the newly appointed architecture critic for the Chicago Tribune (and only a few years away from winning the Pulitzer Prize), wrote a glowing review of Lowe’s book—titled Lost Chicago—that appeared on the front page of the newspaper’s Sunday book section. Gapp called Lost Chicago “one of the best . . . pictorial essays on the city ever produced,” and he quoted an eloquent passage from the book’s introduction.

“Their owners had not saved them,” wrote Lowe, lamenting so many lost buildings. “City commissions had not saved them. They were an incomparable heritage mindlessly squandered, pieces of gold minted by the fathers and thrown away by the sons. I could not save them in their concrete form, but I was determined that somehow I would preserve their spirit. I would do it in the one way I could, by writing a book that would reveal them and their architectural predecessors in all their glory. Perhaps, by showing the splendor which has been lost, I might, in some small way, help to preserve that splendor not yet departed.”

Chicago heeded Gapp’s call, and that December night on the South Side, Sauer’s was packed. “It was surreal,” says Lowe today, still awed by the turnout.

That was only the beginning. Back in New York—where Mark Smith, writing in the Times, lauded the book as “[not] just another coffee table gift . . . [but] a history of the whole city as a cultural creation”—Lowe encountered the novelist Kurt Vonnegut at a cocktail party. “I’d seen Kurt around,” recalls Lowe, but on this occasion, Vonnegut, at the height of his sci-fi-meets-the-counterculture fame, rushed up to rhapsodize about Lost Chicago. “David, this is my favorite book in the world,” he gushed. “I can’t stop reading it.”

At first Lowe was a little perplexed by the older man’s enthusiasm, though he eventually put the praise into context. “Kurt’s father was an architect in Indianapolis,” Lowe explains. “He built wonderful buildings, and most of them have been torn down.” Couple that with the two years after World War II that Vonnegut spent living in Chicago—which Lowe characterizes as the great metropolis of the novelist’s boyhood—and you may have the near-perfect sensibility for appreciating Lowe’s lovingly crafted tribute.

Over the next 30-plus years, Lost Chicago would become one of the city’s most essential books, selling, says Lowe, more than 70,000 copies by 2000. What had originated as a reluctant follow-up to 1968’s Lost New York—and which got under way despite an early editor’s doubts, recalls Lowe, that Chicago had “enough important architecture to make the project worthwhile”—has gone through several editions and publishers, including the latest version, released in October by the University of Chicago Press. (Given the quality of the photo reproductions, Lowe considers this new edition the loveliest.)

Arranged by categories that included residences, railroads, hotels, fairs, and places of entertainment, the book grew larger with each iteration as more buildings vanished. Lowe, who had begun his research during an extended visit to Chicago in the winter of 1973 (holing up almost daily at the Chicago Historical Society), continued to bring other forgotten images to light. For the newest edition, he’s especially happy to have turned up photos of the Arcade Building in Pullman (demolished in 1926–27) and the auditorium (razed in the 1990s) of Hyde Park’s Piccadilly Theatre.

With time, the book’s stature grew. Even toward the end of his life, Vonnegut was still thinking about it, as evidenced by an October 2004 post card he sent to Lowe. “‘Lost Chicago’ is for me the most moving and important American ghost story ever told,” Vonnegut wrote. “I can’t thank you enough for what you’ve done with your lifetime.”

* * *

Photograph: Courtesy of Chicago Historical Society

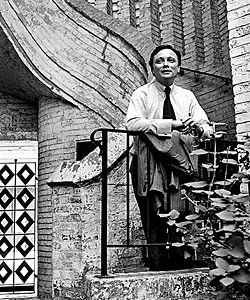

David Lowe on the steps of the Frank F. Fisher Apartments on North State Parkway.

On the surface, Lowe’s lifetime would appear to have only a tenuous connection to Chicago. Born David Garrard Lowe in Baltimore in the 1930s (he won’t be specific about the year), he spent much of his youth in a Kentucky boarding school before heading off to Oberlin College and the University of Michigan, where he earned a master’s in literature. He moved to New York in his early 20s, and he’s lived there ever since.

Young Lowe immediately found a spot in New York’s thriving magazine world. After a stint on the clipping desk at Look, he spent five years at American Heritage when Bruce Catton, the award-winning chronicler of the Civil War, still ran the show. Later, while working as an editor at McCall’s, Lowe sent Vonnegut on a freelance assignment overseas for an article about Africa. In addition, Lowe wrote a number of essays and books about history, literature, and architecture—such as Stanford White’s New York, a 1992 volume edited by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Today Lowe serves as president of the Beaux Arts Alliance, headquartered on 74th Street in Manhattan, and continues to lecture internationally, including a recent series of talks about the wonders of Italy, delivered at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

So whence came Lowe’s love for Chicago? To anyone with access to Lost Chicago, the answer to that question lies hidden in the book’s dedication: “For my father, who first took me to Henrici’s and the Union Stock Yards, and my uncle, who won the American Derby with Windy City.”

Obviously a few words of explanation are needed. Even younger Chicagoans likely know of the city’s storied stockyards, but Henrici’s? Gone since 1962, the German bakery/restaurant was a popular Randolph Street dining destination for decades until it fell to the wrecking ball to make way for the Daley Center. “The loss of Henrici’s was absolutely outrageous,” growls Lowe. “The Civic Center [the Daley Center’s original name] just gutted the liveliness of that part of Chicago. It should have been on the other side of the river, to the west, where it was needed.”

Related:

PHOTO GALLERY »

Pictures from Lost Chicago and David Lowe's own private collection

As for the American Derby, that classic horserace—still staged annually at Arlington Park—dates to 1884, when it was first held at Washington Park Race Track (at 61st Street and Cottage Grove Avenue), one of the great courses of the Gilded Age. The track was demolished around 1907, but a reincarnation appeared in Homewood some 20 years later—and there, on June 15, 1929, a Kentucky thoroughbred named Windy City won the American Derby by a length and a half. Its trainer was Lowe’s uncle Jake.

That information is the wedge that opens up the story of Lowe’s early life. He will occasionally unfurl his memories from those years, and they are almost as rich and valuable a local resource as Lost Chicago itself. Just one problem: He is selective about the details he will release. Ultimately it comes down to the age-old dilemma of a son coming to terms with his father—in this case, a man, Lowe insists, that he never knew well and is only now beginning to understand. “I haven’t resolved it in my own head,” he says, speaking by telephone from New York, a startling admission for a man in his 70s. But Lowe’s father—and his father’s ten siblings—are the key to understanding Lost Chicago and the love for the city that permeates each page of the book. Call it Lowe’s precious inheritance.

* * *

Lowe may be unwilling to discuss his father, but his many aunts repeatedly bob into view, carried along on the waves of his recollections. There was Molly, the eldest, born the day after the great fire of 1871, when Lowe’s grandparents lived near 23rd Street and Indiana Avenue (not far from the site of Lowe’s triumphant book party a century later). And then there was Sabina, who loved to shop on Michigan Avenue—back when it was a collection of elegant low-rise local boutiques—and who spoke about the Kinzies and the city’s other earliest settlers as if she knew them personally. “I could touch my aunt Sabina,” Lowe says wistfully, “and she could touch the beginnings of Chicago.”

Growing up, Lowe’s father and uncle Jake were inseparable. After working in the Union Stock Yards, the two men branched out into the horse trade, selling Shetland ponies and small two-wheeled governess carts to families living in the city’s better neighborhoods. From there it was a natural leap into horseracing, and both men became successful trainers. In 1928, one of Lowe’s father’s horses, Misstep, won the then-prestigious Fairmount Derby and came in second at the Kentucky Derby.

A gregarious man with numerous well-placed pals, Lowe’s father didn’t marry until in his 50s. He met Lowe’s mother at a racetrack; tall, blond, and beautiful, she came from a Kentucky family that raised thoroughbreds. Lowe hints at a passionate but unsuccessful pairing; they ultimately separated, and when Lowe, an only child, was six, his mother died unexpectedly after a simple operation at a Cincinnati hospital left her with a fatal case of blood poisoning.

For the next 12 years, Lowe spent most of his time living at the Millersburg Military Institute outside Lexington, Kentucky. He speaks fondly of the school, which sparked his interest in literature and history. But each summer, the boy would shed his school uniform of Confederate gray and board a Pullman car bound for Chicago. When it arrived in the early morning, Lowe’s father would be waiting at the old Illinois Central Station in Grant Park. They would immediately head to Henrici’s for finnan haddie (smoked haddock) and potatoes. “For a long time, that was my idea of breakfast,” says Lowe. “It was macabre.”

But to a boy who didn’t know otherwise, finnan haddie and all the peculiar, marvelous adventures of those summers in Chicago seemed perfectly normal. He and his father led a vagabond life, moving from one residence to another over the course of the racing season. They would begin in Chicago Heights, not far from Washington Park, staying in the Victoria Hotel, a Louis Sullivan building that’s now long gone. Next they would rent a house in Arlington Heights near the new racetrack there, and then conclude their tour by staying at the Midwest Athletic Club facing Garfield Park, a good jumping-off point for the Hawthorne track. Aunt Mae lived nearby in the Guyon Hotel, and young David would often go across the street to the Paradise Theatre—another casualty that would find its way into Lost Chicago—where he was dazzled by the sight of Apollo (as rendered by the sculptor Lorado Taft) racing his chariot across the theatre’s twinkling “sky.”

Photograph: Courtesy of David Lowe

Related:

PHOTO GALLERY »

Pictures from Lost Chicago and David Lowe's own private collection

In retrospect, Lowe marvels most at how, from the age of six, his elders generally left him to himself, and how as a boy, alone—though rarely lonely, he claims—he fearlessly explored Chicago by bus, train, and el. At times he would inhabit his father’s thrilling world—not only the track, but the theatre, the ballpark, and the saloon—while at others he explored the museums and bookstores that were entirely foreign to his dad. “There were no books in our house except for studbooks and racing forms,” he recalls, and his father’s efforts to interest him in a job at the stockyards (that visit referenced in Lost Chicago’s dedication) fell flat. “I saw them killing animals, and you could smell the blood,” he remembers. “I’m glad I saw whatever I saw, but that was enough of that.”

After finishing his secondary education at Millersburg, Lowe made his new home at Oberlin College in Ohio, for which his aunt Gertrude picked up the tab. (Lowe’s family had vetoed his first choice, the University of Chicago, deeming it too leftist.) In 1955, the year Lowe graduated from Oberlin, his father died of intestinal cancer at a Chicago hospital. After the funeral, his elders again left the young man alone. That afternoon, at the Loop Theater (gone!) on State Street, he sat through four showings of the Katharine Hepburn movie Summertime. A few years later, New York became his permanent home, but the Chicago memories were indelible.

* * *

In Slaughterhouse-Five, his best-known novel, Kurt Vonnegut explains the concept of time on the distant planet Tralfamadore: “All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist,” he writes. “The Tralfamadorians . . . can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them. It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone it is gone forever.”

Maybe it’s the confluence of his colorful childhood and his friendship with Vonnegut, but Lowe’s memories seem to unfold in Tralfamadorian time. Prefer a walk through Chicago without encountering Macy’s? Just cast your gaze at a moment—any moment—before that New York intruder landed in the Loop.

“There are only two cities in America,” contends Lowe. “New York and Chicago. Boston is a nice little town, but when you get downtown in Chicago, you know you’re in a real city. My favorite spot in the world is coming up the stairs out of the Randolph Street station. You go look in the windows of Marshall Field’s, and the el is running overhead. An urban sound. I love the el. I hope they never tear it down.”

But memories are perishable, too. Lowe talks of writing a Chicago memoir, but he first has to straighten out his own relationship to those memories. He would be wise to remember a project that he and Vonnegut once tossed around. “Right before he died,” Lowe says, “Kurt wanted us to do a book about the loss of urban life in the Midwest. We would get in a car and go to strange cities. I would check up on the architecture, he would write his impressions, and Jill Krementz [Vonnegut’s wife] would do the photos. Not a bad idea”—but Vonnegut’s death in April 2007 put an end to all that. So it goes.

Having fulfilled—and built on—his early aspiration of preserving the city’s splendor within the silvered pages of Lost Chicago, Lowe might still one day conjure up the eccentrically populated city now confined to his mind. Hopefully that day will come soon. Here on planet Earth, the clock is ticking.