Ewing owns perhaps the nation’s largest private collection of sports films—more than 3,000 reels in all.

Related:

MORE COLUMNS BY EIG

The Bulls’ Secret Weapon: Tom Thibodeau »

Chicago Baseball Preview: The Most Dismal Season in 30 Years? »

Lovie Smith on Keeping His Cool »

Can Theo Epstein Deliver for the Cubs? »

Rosemont-based Riddell Seeks to Build a Safer Football Helmet »

Adam Greenberg Dreams of Making It Back to the Majors »

For the Chicago Comets, Blindness Is No Impediment to Tough Competition »

Six Decades After His White Sox Debut, Minnie Miñoso Still a Fan Favorite »

Laurie Schiller, the Most Successful College Coach You've Never Heard Of »

On a gray Monday morning in Naperville, Doak Ewing sits in a comfortable chair in his living room, his big hands stabbing at the air as he speaks, explaining to me exactly how I am going to write this column.

“The first thing you have to ask yourself is this: Why should someone be interested in me?”

I nod, waiting. But not for long.

“That’s easy! I do something no one in this country’s ever done before!”

Ewing, 63, is a big, broad-shouldered man with thick graying hair and a white mustache. He is wearing loose-fitting jeans and moccasins. He looks like a first baseman 25 years past his playing days, but he speaks with the energy of a kid just out of college. He sounds like an old-school radio broadcaster or the guy from a Movietone newsreel, heavy on the exclamation points.

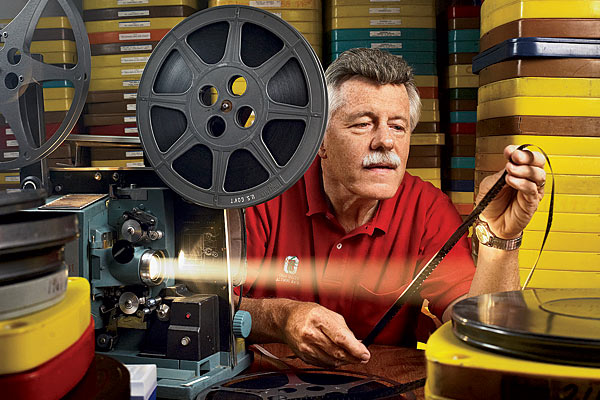

Ewing is the owner and sole operator of Rare Sportsfilms. He maintains what is perhaps the nation’s largest privately held collection of sports films, with more than 3,000 reels of the good old pre-VHS, pre-DVD stuff. Jim Gates, librarian at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, calls Ewing “one of the all-time collectors of sports video.” He knows of no one with a bigger collection.

Ewing keeps it all in his basement. Day and night, seven days a week, he’s down there running films on an old Bell & Howell projector, cleaning them, splicing them, editing them, preparing them for transfer to DVD. He’s restoring history, that’s what he’s doing. Restoring memories. Retelling stories.

Maybe that’s why he is intent on telling me how to write this column. Every one of those old films is a story waiting to be told. And so is Doak Ewing!

Sorry, Doak, didn’t mean to get in your way.

“The next question is: Why has no one ever done this before? Because you have to have three things, and I’m the only one who has them!”

I don’t have to ask him to name the three things. He’s already telling me.

“The main one is you have to have the films,” he says. “That’s number one! Then you have to have some knowledge of copyright laws. You don’t want to have to pay a bunch of lawyers all the time to find out if you can sell your DVDs. The third thing is you have to have knowledge of sports. Let’s say you’re looking at an old film of the Philadelphia Athletics from the 1930s, and one of the players is Chuck Klein. You need to know, Hey, that’s Chuck Klein! And let’s say it was shot at the Baker Bowl. There’s hardly any footage of the Baker Bowl! There are collectors who are interested in that!”

Ewing has been accumulating old 16 mm films for more than 25 years now. They date from the thirties to the early eighties and include team highlight footage, league productions, beer company films, documentaries, network broadcasts, and even a few home movies. He gets them at garage sales and flea markets, through classified ads, and on eBay, typically paying from a few bucks to $200. See footage of the 1935 World Series between the Cubs and Detroit Tigers below.

He takes me into his basement, which is decorated with an Old Milwaukee sign and some photos of the Ohio State marching band. The Bell & Howell is aimed at a bare wall. Film canisters and DVDs are stacked on shelves, packed in boxes, and piled on the floor. It’s a man cave if ever there was one.

Ewing never uses the word “obsession,” but it’s hanging in the air, like the dust that floats in the light of his projector’s beam. The thought of some film—any film—rotting away or winding up in a landfill eats at him, as if he has a responsibility to save it. Some people rescue stray cats; he rescues old movies. This, after all, isn’t just his business. It’s a hobby that became a passion that, almost accidentally, became a livelihood. With his vast supply of old films, Ewing produces about 15 new DVDs a year, listing them at RareSportsfilms.com.

You want Milwaukee Braves highlights from 1953 to 1955? He’s got them. Kansas City Athletics footage from 1956? The NBA All-Star Game from 1962? Check and check. He collects baseball games, football games, Indy 500s, NASCAR races, NBA games, and PGA tournaments. What? No hockey? He has highlights from the 1954 Stanley Cup finals—Red Wings versus Canadiens, considered one of the greatest Cups of them all—but that’s it. A man has got to draw the line somewhere.

Most of the videos sell to fanatics, but a good many go to ordinary people with particular interests. Say your grandfather played football for Notre Dame in 1953. For $29.95 plus $4 shipping and handling, you can see him in action.

Ernie Accorsi, a former NFL general manager who claims to own almost every film in Ewing’s catalog, says Ewing’s work stands out for the quality of his editing and the sharpness of the images.

* * *

“I suppose I should tell you how I got started,” Ewing says.

Uh, yes.

“I’m a farm kid,” he begins. “I grew up on a farm in Ohio, and we never had TV in the house because Mom wouldn’t let us. But my dad was on the board of the Guernsey County Library. He loved gadgets, and he brought home a projector and some movies from the library. He taught me how to put on a film, how to splice film, how to edit.

“After college, I wanted to get into baseball. I got a job with the Atlanta Braves, in the minor leagues. In 1980, I went to work in sales for the big-league team. I was cleaning out a room in the bowels of Atlanta Stadium one day when I found all these old films they were going to throw out! They let me keep all the duplicates. And that got me wondering: How many of these are out there? Do they still make them? What else is out there?”

Ewing put an ad in The Big Reel, a magazine for film collectors, indicating his interest in buying old sports films.

He began showing the films to some of his friends. “One night, one of the guys said, ‘Doak, why don’t you put these on VHS and sell them? You’d make a mint!’ So I took a film of the Boston Braves from 1947—it was vintage color—and I put it on VHS. Well, it didn’t sell very well! How many people were really going to be interested in a defunct team? But I went to baseball card shows and started selling my videos. Remember, there was no ESPN! There was no MLB Network! There was nobody showing old sports at all! Period! The first year, I sold maybe 50 films. But I was having fun. It was a great hobby.”

In 1986, he moved to Chicago to take a sales job with the White Sox. After a few years, his income from video sales matched the income from his nine-to-five. At about the same time, he met his wife, Cheryl, who encouraged him to start his own business.

* * *

Ewing doesn’t expect he’ll ever get rich from his massive catalog. Most videos sell only a few copies a year. Several years ago, he did make a big find, releasing the only known copy of the telecast from Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series. The discovery brought him nationwide attention, and the DVD became a big seller. But other than that, he works mostly in obscurity.

“How long will I keep doing this?” he asks. “That would be another good question. I don’t know. The problem is, it’s my hobby! If I retired, I’d still do it!”

A better question, perhaps, is this: What happens to these films when Ewing reaches the end of his reel? He’s got no children to inherit the collection. Will some other hobbyist buy his films and continue the business? Will this stuff wind up in a museum? Ewing is not ready for any such talk. As the ballplayers say, he’s got a lot of good years left.

“Bottom line, this is your story: Here’s a guy in Chicago. He’s doing something nobody else does! He’s got a great wife! A great business! He seems to be successful and happy. That’s just about it. That’s your story!”

Photograph: Nathan Kirkman