For a time, if you were at any high-society event around Chicago, you probably saw Jerry Berliant. He’d pop up in Super Bowl suites, too, and even at the Oscars. Who was he? Not some mysterious billionaire or celebrity of any conventional sort. Cubs announcer Jack Brickhouse once described him as the “world’s greatest gate crasher” — a man with an unusual talent for sneaking into exclusive places with tight security. Berliant had an abundance of free time for his hobby, having been convicted of tax fraud as part of Operation Greylord, the FBI probe into corruption in Cook County’s judicial system, and disbarred. Ted Allen took the first real stab at figuring him out for the 1995 Chicago story “Anybody’s Guest.”

Berliant has never been fully profiled, and at first he declined to be interviewed for this story. But when told it would appear anyway, he agreed to meet several times, once showing up for an interview with three typewritten pages of questions he thought should be asked — and his answers to them. A sample: “If I had to do it all over again … I’d like to come back as a woman — the doors [would] open up a little easier that way.”

In 2007, Berliant was in the news again: He owed the city nearly $30,000 in parking fines. At the time, he told the Sun-Times he had given up the interloper life. But the next year, he was arrested on suspicion of trespassing and evasion of an admission fee for sneaking into an NCAA tournament game in Denver. Police found on him various fake press credentials and bogus business cards. When Chicago reached Berliant to ask what he thought of Allen’s story 25 years later, he had only one thing to say: “That’s all behind me now.”

Read the full story below.

Anybody’s Guest

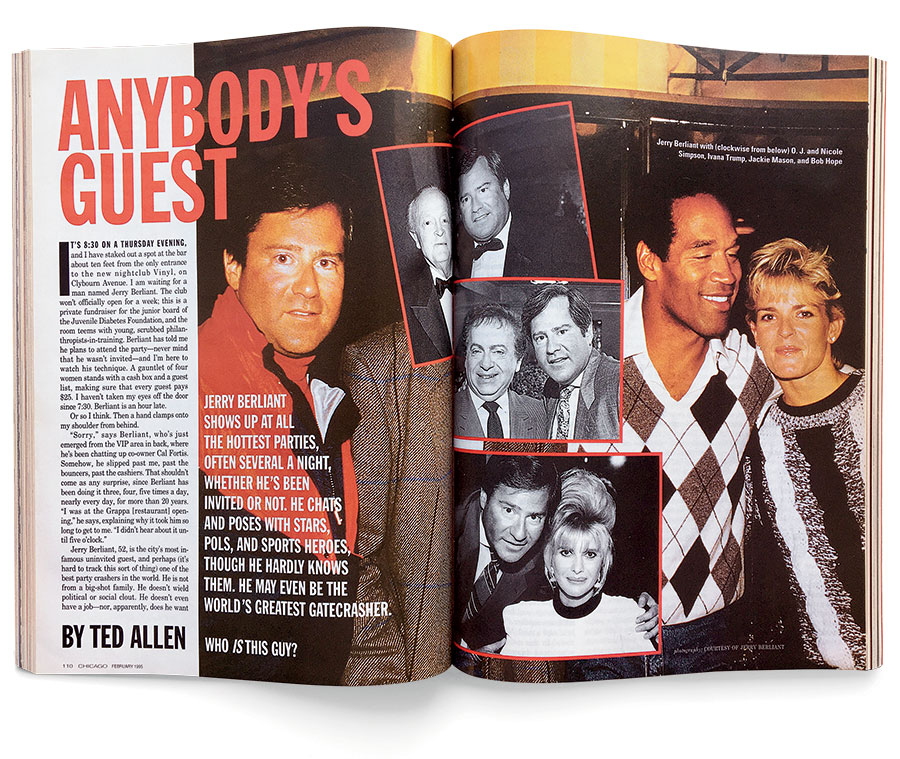

Jerry Berliant shows up at all the hottest parties, often several a night, whether he’s been invited or not. He chats and poses with stars, pols, and sports heroes, though he hardly knows them. He may even be the world’s greatest gatecrasher. Who is this guy?

It’s 8:30 on a Thursday evening, and I have staked out a spot at the bar about ten feet from the only entrance to the new nightclub Vinyl, on Clybourn Avenue. I am waiting for a man named Jerry Berliant. The club won’t officially open for a week; this is a private fundraiser for the junior board of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation, and the room teems with young, scrubbed philanthropists-in-training. Berliant has told me he plans to attend the party — never mind that he wasn’t invited — and I’m here to watch his technique. A gauntlet of four women stands with a cash box and a guest list, making sure that every guest pays $25. I haven’t taken my eyes off the door since 7:30. Berliant is an hour late.

Or so I think. Then a hand clamps onto my shoulder from behind.

“Sorry,” says Berliant, who’s just emerged from the VIP area in back, where he’s been chatting up co-owner Cal Fortis. Somehow, he slipped past me, past the bouncers, past the cashiers. That shouldn’t come as any surprise, since Berliant has been doing it three, four, five times a day, nearly every day, for more than 20 years. “I was at the Grappa [restaurant] opening,” he says, explaining why it took him so long to get to me. “I didn’t hear about it until five o’clock.”

Jerry Berliant, 52, is the city’s most infamous uninvited guest, and perhaps (it’s hard to track this sort of thing) one of the best party crashers in the world. He is not from a big-shot family. He doesn’t wield political or social clout. He doesn’t even have a job — nor, apparently, does he want one. He is a former lawyer who surrendered his license and served 20 weekends in the downtown Metropolitan Correctional Center after pleading guilty to tax fraud in the Greylord investigation (although he’s still listed in the phone book as an attorney, at a Loop address that houses an answering service). Yet thousands of the richest, most powerful people in American business, philanthropy, sports, and media have shaken his hand, posed for photos with him, fed him, and filled his wine glass. He has been to Hef’s mansion. He’s been to nearly every Super Bowl. He was at Bill Clinton’s inauguration, the wedding of Charles and Di, the opening of the fabled Faces nightclub. He shows up in the press box at Notre Dame football games, Bulls championships, Kentucky Derbies, the Final Four. He drove Jackie Mason in from the airport when the comedian arrived here for a benefit last November. He has mugged with Bob Hope at the comedian’s celebrity golf tournament near Palm Springs, partied with O.J. and Nicole in Aspen, schmoozed Donald and Ivana at their respective book parties, and had smoke blown in his face by Howard Cosell. One Thanksgiving Day, he arrived, unannounced, on the doorstep of restaurant mogul Richard Melman’s house, and flustered Melman’s wife so much that she dropped the turkey on Berliant’s foot. He’s been called a freeloader, a mooch, a sponge, a deadbeat, and a cad, as well as Jerry the Crasher, Crash, and a crashing bore. There’s hardly a reporter, press agent, politician, or socialite in Chicago who doesn’t know him.

Then again, there’s not one who does.

Jerome Bernard Berliant has terrific, minty breath. I ask if he’d like a drink. “Yeah,” he says, standing beside me at the Vinyl bar. “The Lake Shore Drive [magazine] party won’t start until nine.” He’s wearing a blue pinstripe suit he later confides to me is an Armani; there’s a ring on his right ring finger that contains a Krugerrand surrounded by sparkly diamonds, and he has cinched his usually unbuttoned collar with a rep tie. He is five feet ten inches tall, and has a deep tan, a thick shock of black hair, and brown eyes. He leans less than a foot from my face as he gossips about Oprah (“I can’t even get through to her assistant; it’s like a fortress over there”) and Christie Hefner’s relationship with former Illinois state senator William Marovitz (“If it weren’t for him, she’d be home by nine. He introduced her to a lifestyle”).

Berliant has never been fully profiled, and at first he declined to be interviewed for this story. But when told it would appear anyway, he agreed to meet several times, once showing up for an interview with three typewritten pages of questions he thought should be asked — and his answers to them. A sample: “If I had to do it all over again, … I’d like to come back as a woman — the doors [would] open up a little easier that way.” (“Don’t let him fool you into thinking he doesn’t like this,” Melman said later.) Tonight, Berliant is letting me follow him on his rounds of the city’s openings and receptions. We step out onto Clybourn, and Berliant offers to drive to the next event. In a rented white Oldsmobile with Utah plates, he offers a chocolate from a gift bag distributed at the Grappa party. “Oh, the tiramisù,” he says. “I had four pieces.”

The door at Cairo on Wells Street is cordoned with velvet ropes and guarded by beefy guys with walkie-talkies. “Where are Bill and Liz?” Jerry asks one of them, as if he were the hosts’ guest of honor. The bouncer points upstairs.

That’s all there is to it. We’re in.

Not that this was a tough party to crack — it’s one of many being thrown by the new society-gossip magazine Lake Shore Drive. Berliant picks up five copies; he will carry them for the rest of the evening. The room swarms with middle-aged men with hairy chests, gold chains, savage tans, and suspect hair. There’s also a clutch of models in tiny dresses, because tonight’s party features a contest for an appearance on the magazine’s cover. Berliant threads easily through the packed room, his eyes scanning for people he knows. During the course of the night, he introduces me to his dentist, who suggests I write a story about his practice; LSD publisher Bill Von Dahm; a man who runs a singles-party service called Terribly Smart People Productions; a divorced Cook County Circuit Court judge, who dances awkwardly during lulls in conversation; the owner of the restaurant Bijan, who suggests I write a story about him; and a furniture designer, who also suggests I write a story about her.

I suggest cocktails. “I’ll have Finlandia and cranberry,” Berliant says. “Finlandia’s on the house.”

Berliant sticks close to me all night. He seems glad for the company, which is understandable — he always makes his rounds alone. Some of the people who clearly are regulars on the party circuit, and who have bumped into Berliant for years, are cordial. But many socialites and party planners — including tonight’s promoter, LSD’s Melissa Brown — respond to him with visible disdain. Brown smiles wanly, meets me unenthusiastically, then is suddenly possessed of the immediate need to do something important on the other side of the room. Berliant doesn’t seem to notice.

Janet Kerrigan is the director of public relations and promotions for Melman’s restaurant group Lettuce Entertain You, and a former employee of Margie Korshak’s PR firm here. She’s been in the publicity business since 1980, and says she can’t remember a single Lettuce restaurant opening that Berliant didn’t attend. “It’s become a joke,” she says, and then repeats an axiom uttered by every flack in the city: “It’s not a party if Jerry isn’t there.” But she’s as mystified by Berliant as everybody who’s heard of him. “What I don’t understand,” she says, “is why anybody would want to spend all their time going to parties that they’re not invited to.”

“Every time I look at him, I just want to kill him,” says one of Chicago’s best-known press agents, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “The guy is a sponge, and he’s just everywhere,” says another. “I think he is just a jerk,” says a third. All the PR people interviewed for this story had tales of trying, sometimes unsuccessfully, to eject Berliant from events. Most say that they usually just shoot him daggers, grit their teeth, and hope he leaves before long.

Here’s Berliant’s typical modus operandi: The opening of Erie Cafe, last September seventh, was a large, packed affair with an excellent buffet and lots of West Loop political types. Berliant showed up wearing a brown wool jacket, a white golf shirt opened to the sternum, and loafers. He patted the doorman on the shoulder as if they were old friends, and walked right in. He ambled through the thick crowd around the food, diving in for a cocktail shrimp now and then, slurping red wine. Every ten feet or so, he spied someone he recognized, and began chatting — never for more than a couple of minutes. Then he moved on. “Every time I run into Jerry, he gives me his weekly agenda,” says Sun-Times columnist Bill Zwecker. The agenda usually occupies Berliant’s brief conversations: Just got in from Atlantic City. Did you hear about the Escada party? Are you going to B. J.’s reception?

James Warren, a Tribune editor who used to wrik the column “On the Law,” once observed in print, “Some people are convinced that if you look closely at Loonardo da Vinci’s painting of the Last Supper, you’ll find Chicago attorney Jerry Berliant hovering in the background.” But nearly everybody’s got a story about Berliant that really happened. “The opening of Bloomingdale’s was certainly one of the biggest retail openings in the city,” recalls Sue Chernoff, a vice-president for (and a daughter of) Margie Korshak. “There was only one entrance and there were 20 people doing checking and security — ID was required. I just remember thinking there was no way that Jerry could get in. Two hours into the party, I looked up, and he was floating in the crowd.”

Of course, that was a big party. More baffling is how Berliant hears about the smaller, more exclusive events. “I did this party at a restaurant, invited only 30 or 40 people, and Jerry showed up,” Chernoff says. “How the hell did he find out about this thing?” Richard Melman recalls, “We always have these Thanksgiving parties, and one year, there was a knock at the door and there was Jerry asking what was going on.” Melman’s wife, Martha, chimes in: “He didn’t stay for dinner. He just hung around the kitchen, and he stood right by me as I was trying to take the turkey out of the oven. He didn’t give me any elbow room, and I dropped it right on his foot. He didn’t miss a beat.” Perhaps he didn’t notice — Berliant does not recall a turkey ever landing on his loafers.

“I have a tremendous network,” Berliant explains. “I talk to California, New York, practically daily,” he says, not to mention the workout his phone gets with local reporters, restaurateurs, promoters, and pals. “I show up at a lot of places, and I talk to a lot of people and I seem to have a good memory, mind for people, places, things. I know what’s happening all the time.”

Mary Cameron Frey, who covers benefits for the Sun-Times, has less affection than most for Berliant. She once slammed him as a deadbeat in her column, earning howls of protest from Berliant and sealing a mutual loathing that’s still intense. (Bess Winakor, a former Sun-Times staffer who in 1976 wrote a fairly gentle story on Berliant, says she drew his ire, as well. “Jerry was livid. He threatened to call [restaurateur] Arnie Morton, and said Arnie would get me fired.”) Frey’s beat fates her to run into Berliant routinely. “I have watched him very carefully sneak into rooms,” she says. “He oils his way in. He sticks close to walls. He showed up in the owner’s box in the new White Sox park; [Sox owner Jerry] Reinsdorf had him ejected. He came back the next day and was ejected again. The man’s middle name has got to be ejection.” (Berliant denies ever having been in Reinsdorf’s box.) At another function, Frey recalls, “Governor Edgar said to me, ‘Who is that man?’ and I said, ‘He is a disbarred attorney. He is a person who attends events he isn’t invited to.’ And [Edgar] said, ‘åI was in [Chicago lawyer] Irwin Jann’s box at the Kentucky Derby, and all of a sudden, that man is standing in the box with his arm around my shoulders, having my picture taken.’ ”

Not everyone on the local party scene, however, considers Berliant a persona non grata. Many see him as an entertaining — and even valuable — source of information. “I think that’s his ticket to get in,” says Melman, who takes Berliant’s phone calls when he isn’t too busy. “He travels an awful lot, and he usually tells me what’s going on in California or New York. I get a little capsule of what’s hot.”

Others seem genuinely fond of him. Ann Gerber, the society columnist at Skyline and other Lerner newspapers, says Berliant was kind when the Sun-Times ousted her over an item about Oprah Winfrey. “When I was fired during the big Oprah scandal, he called me several times and asked, ’Is there any way I can help you?’ ” Gerber says. “I wasn’t writing anywhere. He wasn’t looking for publicity. And I didn’t even know him.” Long-time restaurateur and club impresario Jimmy Rittenberg also has a soft spot for Berliant. “He’s not a bad guy,” Rittenberg says. “He’s an interesting guy who just happens to like being in the right place at the right time. I like Jer. If l want to start the ball rolling on something word-of-mouth, I tell Irv Kupcinet, and then I tell Jer.”

Berliant knows he has critics. “They just try to make themselves feed off of me, make themselves bigger, more important,” he says. On the Q&A he typed for me, he defended himself, arguing, “If I said I never showed up anywhere with my name not being on the guest list or without a ticket, I wouldn’t be exactly truthful.” But, he insisted, he’s never been “thrown” out of a party. “I have been asked to leave. I like to think there is a difference.”

Berliant settles into a booth at Hubbard Street Grill, and orders black coffee and a green salad “chopped extra fine” — he’s just returned from a “fat farm” in California, the name of which he refuses to reveal, where he shed more than 30 pounds. “Those ten-mile jogs at 6 a.m. were rough at first, and eating fruits and vegetables wasn’t exactly my idea of party food, but you do what you have to do,” he says. “I pay for these parties, one way or another.”

His battle of the bulge is one of the few personal details he will offer at this meeting. He declines to talk about his childhood, his family, or anything else private except vaguely — he even refuses to give his parents’ names. “I’ve got nothing to hide,” he says, “but that was so long ago. I don’t know if the exact detail would be that important.” He speaks in a rambling stream of consciousness, using incomplete sentences that usually trail off and are hard to follow. Some of the Berliant story can be pieced together, though, from interviews, documents, and other sources.

He was born on September 18, 1942, on the North Side. His father, Ernest, a Chicagoan of French-Canadian descent, was a pharmacist (he died in 1972); Ernest owned the Berliant Pharmacies, of which there were once several. The one tiny store that’s still in business, at 36 South Michigan Avenue, is run by Jerry’s only sibling, Norman, who is two years younger and lives in Wilmette. Norman says he has nothing to add to his brother’s story. “You probably know more about Jerry than I do,” Norman says over the counter in the pharmacy. “I don’t see him very much.” Ernest sometimes took his boys to the drugstores, Jerry says, where “he more or less babysat us.” Their mother, Beatrice, died in 1993 after a two-year illness. People who know Jerry say he called or visited her nearly every day in the nursing home.

He started high school at Senn, not far from his West Ridge home, but somehow got a transfer to Lake View. As a junior, he was invited to join the Nobles club, a social-athletic group. He earned a bronze pin from the Hi-Q honors society and served as class treasurer before graduating in 1960. But classmates say Berliant was a loner who, even then, kept track of what everybody else was up to — and tried hard to fit in. Joel Zimbroff first met Berliant in high school. Now, ironically, he is head of security for Lettuce Entertain You. “He was very pushy,” Zimbroff recalls. “There was a deli called Leonard’s and the kids would meet there after school and talk among themselves. Jerry would just be there. We used to meet at the totem pole at Waveland park after school and Jerry would always be there. You could spit in his face and he would say, ’It must be raining in here.’ You can’t insult him. He was just a guy who was overly aggressive in wanting to be part of a crowd.”

Ernest Berliant hoped to hand down his business to his sons, but Jerry wasn’t interested. “It just was a field that was too limited for me,” he says. So Berliant studied business at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, then returned to Chicago to earn a law degree at DePaul University. His classmates included Ed Burke, now a prominent member of the City Council, and Richard M. Daley. “Eddie, I think, was in night school,” Berliant says. “I saw him from time to time. Mayor Daley was in my class. We were fairly on good terms. We weren’t best friends, but Richie was a likeable fellow.”

Berliant passed the Illinois bar in 1970. He says he clerked with a few lawyers, and thought about applying to firms, but decided to open a one-man shop. “I was always an independent guy, getting things together myself, working on my own, he says. “I wanted to get some trial experience, so I took myself into the criminal courts and watched and went to trials and basically learned it by myself.”

Apparently Berliant learned enough to make a decent living. He won’t talk about his former law business, except to say he handled “a lot of small clients. I can remember, in the seventies, after I went out on my own, I made good money.” And that’s when he started traveling and gate-crashing, popping up in press boxes, at celebrity weddings, on the field at Super Bowls. “Being single, not having any dependents, you were able to pretty much go,” he says. Indeed, Berliant had few expenses; he lived with his mother in her 1,500-square-foot yellow-brick bungalow built in 1928 on a tree-lined street near Devon and Western (the house now belongs to Berliant, and he still lives there). He has never been married, and he says he’s not seeing anyone. “Although I’ve been single all my life, the book isn’t closed yet,” he says. “I’m open to it.” Of course, there’s the problem of finding someone who could tolerate his passion for the nightlife. “I’ll say, ‘I’m going out tonight,’ and she’ll say, ‘Well, you’ve been out the last 948 nights.’ ” But, he adds with a laugh, if romance ever did blossom, “I would take her with.”

In the beginning, Berliant says, crashing was easier. “As you got to meet people and travel and know people in the media, you would get to know your way around, and you could take advantage,” he says, meaning he sometimes gets reporters to lend him their press credentials. That’s how he got into Prince Charles and Lady Diana’s wedding in Saint Paul’s Cathedral in 1981. “Twenty-five years ago, anybody could virtually walk anywhere. You could do anything but get on the field and start playing, as long as you weren’t in the way of the cameras. It all changed, I’d say, about 15 years ago. When Reagan got shot by Hinckley, ever since then, [security types] have been overachievers. It’s more difficult to get where you aren’t supposed to be. You’ve just got to be more creative.”

Berliant became a fixture at every restaurant unveiling, every society ball, was one of the first ten people inside Faces (he paid the $50 introductory fee, but later relinquished his membership in the nightclub after a dispute with co-owner Jay Emerich). He established himself as an extremely visible Chicago character, providing regular fodder for gossip columnists and earning the passionate enmity of PR people — who value, more than anything, complete control over what happens at their events. But except for Winakor’s short profile in 1976, no one paid more than passing attention to his doings. In 1985, that would change.

The Operation Greylord probe was the most sweeping blow to governmental corruption in Chicago’s sordid political history, and it brought down many powerful men. It also inadvertently knocked off some much smaller fry. One of those was Berliant, who worked and hung around with lawyers, cops, and judges of the Cook County Circuit Court in the Daley Civic Center. Berliant was indicted on two counts of tax fraud for failing to report about 80 percent of his income in 1978 and 1979.

The courts commonly route payment to defense attorneys directly from the bond money posted by their clients. Agents from the Internal Revenue Service were checking Chicago Lawyers to be sure that the income was reported on their tax forms, because those funds were thought to have been often used to pay kickbacks to judges. Ira Raphaelson, than an assistant U.S. attorney (now in private practice in Washington, D.C.), presented evidence that Berliant reported only $6,300 in income in 1978, when he actually had earned $54,000, and reported $10,542 the next year, when he had brought in $63,000.

Raphaelson said Berliant had cashed bond checks at currency exchanges, restaurants, “and in one case that we found, with a bookie.” While prosecutors characterized Berliant as a high liver because of his travels to sports events and cited his penchant for “spending a great deal of time on Rush Street,” even then it was clear he spent almost nothing on his business. “In his peak income-producing years as a lawyer,” Raphaelson told the court, “all he had was a part-time secretary and an answering machine, no office.” Today he stills uses the same business address, 201 North Wells Street, No.1206 — which is actually a dilapidated suite with an enormous antique plug-in switchboard worked by a woman who says she takes calls for more than 1,000 people. A sign on the door reads PHONE SERVICES UNLIMITED.

Berliant submitted a psychiatrist’s report that blamed his behavior on a “narcissistic personality.” Raphaelson told the court, “It is, frankly, an outrageous position to take, that having a narcissistic personality in any way mitigates the gravity of this offense.” The judge agreed, saying, “[T]he psychiatrist essentially says that he is too self-centered. That would be true of a lot of people.” Berliant pleaded guilty on March 30, 1985. His attorney asked that he be sentenced to community service at a Shriners’ hospital for hnndicapped children. The judge decided instead to sentence Berliant to 20 consecutive weekends in jail, beginning on June 7, 1985, and to three years’ probation, forgoing any fines because “his financial circumstances at the· present time are quite meager.” He also ordered Berliant to pay his tax debt. The next year, Berliant agreed to be disbarred by the Illinois Supreme Court.

“I really had nothing to do with the Greylord situation, per se,” Berliant says. “Somehow I just got put in this dragnet. It was a war on lawyers. I didn’t have the right answers at the time. Basically I didn’t do anything. But they did put pressure on people in my business, people around me, and I just wanted out.” He says today that he doesn’t miss the legal profession. “There’s no fun anymore. You’ve got to be careful who you talk to. You go to the courthouse and nobody would talk to anybody, everybody thought that everybody else was tape recording everybody else, so it became no fun. We used to have a lot of talk, camaraderie. And I had had 20 years of it.”

His weekends in jail began at 5 p.m. Fridays and ended at 8 a.m. each Monday, a type of sentence usually intended to help prisoners hold down regular jobs. But that’s not how Berliant spent his weekdays. According to the Tribune’s Warren, between sessions in the pokey, Berliant was spotted at the Brian Piccolo charity golf tournament and in the press tent at the Western Open.

It’s too facile to suggest that Berliant stays alive by munching other people’s hors d’oeuvres. How does he pay his bills? “I don’t know whether we ever figured that out,” Raphaelson says today. Although he was a practicing lawyer for more than 15 years, there is no evidence that Jerry Berliant has worked a single day since he was indicted in 1985, and he offers no proof to the contrary. Some people speculate that Berliant is a mole for the CIA, the IRS, or the U.S. attorney’s office, and that his hail-fellow-well-met style is an act. (Berliant dismisses the rumors as ridiculous.) “It’s disarming,” a politically connected local developer says of Berliant’s demeanor. “Some people may think he’s a buffoon, that he’s just a social climber, but the conclusion of most people in public office is that he’s like Columbo” (the TV detective who pretended to be a bumbler, but wasn’t). “He’s too alert to just be rambling. He’s nice, but when I see him coming, I say hello and walk the other way. There’s a lot more to Jerry Berliant than meets the eye.” Perhaps, but the spy theories fail to address why any of those organizations would care what’s happening at black-tie parties and in NFL locker rooms.

Another rumor was probably born in a May 1985 hearing on Berliant’s tax case, in which Raphaelson contended that Berliant “served as a bookmaker in … one instance,” but was referring only to a single bet Berliant allegedly placed for a friend. He’s never been charged with a gambling offense.

Information gathered for this story suggests that Berliant is frugal and smart with his money. He doesn’t run up balances on his credit cards, and there is no record of his carrying any other debt. His mother split the family estate evenly between Norman and Jerry (the file in probate court contains no estimate of its value). According to the office of the Cook County Recorder of Deeds, Norman signed over his share of the house to Jerry in 1993 for $70,000. Jerry may have inherited other assets from his parents, as well. In fact, records show his $25,000 tax lien wasn’t released until July of 1993; it’s possible that he used some of his inheritance to pay the debt.

“I’ve made some good investments over the years, stocks, equities, which I still have,” he says. “I’m comfortable enough to support my style of living. I’m not looking to be in a penthouse or anything like that.” He sometimes wears designer suits, but often dresses in casual, less expensive clothing. There is no record in Illinois of his owning an automobile, although Zimbroff says Berliant drives a “beater” and rents nicer cars when he wants to make a better impression. His major expenditures are flights to and lodgings in places like Aspen — bills that Berliant says can run $3,000 a week. “It costs, ” Berliant says. “This is the nineties; this is what it costs. With your fun, with your food, with your go, you can run those kind of bills.”

But what motivates a man to spend so much money and so many years making small talk over cocktails, under the baleful gazes of unwilling hosts? “I go because I enjoy it,” Berliant says. “No one compels me or pushes me to do all this. You’ve heard the expression, ‘He who has the most toys [when he dies] wins.’ I look at it as ‘He who has the most options wins.’ It’s nice to be able to wake up every morning and say, ‘Let’s see, here’s ten things to do. What do I want to do?’ ” His detractors, he argues, just wish they could be playboys, too. “I don’t have a deadline. I don’t have a typewriter; they do. ‘Why isn’t he married, like I am? Why doesn’t he have five kids, like I do?’ I don’t begrudge anybody. You do what you have to do.”

These days, Berliant has become such an institution that people sometimes invite him to parties — such as a DePaul University sports-media luncheon at Bub City last November. In 1993, local club owners arranged a party for Berliant, then invited people to “crash.” Berliant has even been caught recently paying for events. “He actually bought a ticket either to the Variety Club party or the Academy of the Arts,” Zwecker says. “I was so shocked that I can’t remember which charity it was.”

“He buys tickets for more things than people realize,” says Ann Gerber. “He has paid for at least four things this year.” But nobody really expects Berliant to start RSVPing all of a sudden. Some people would probably be disappointed if he did.

Back at Cairo, the free drinks have stopped flowing, and the Lake Shore Drive party is winding down. Berliant is talking with the singles-party promoter about some wingding over at America’s Bar at 11. Doesn’t sound so great, he concludes. I tell Berliant I’m tired, and he walks down the stairs to see me off. Melissa Brown barks at Berliant for taking his cocktail glass outside. “It’s empty,” he assures her. He asks me what parties I’ll be hitting this week; then, before I can answer, he tells me which ones will be hot. I wave goodbye; he’s staying for the models contest. He turns to chat with Brown, who busies herself tidying things up, and he then ambles back upstairs. “Someone said that showing up is 75 percent of life,” Berliant had told me earlier. “If that’s true, I’ve really led nine lives.”