What you are about to read is a story of human endurance. A story about a come up so insane you’d think it’s a lie. Some Netflix shit. But it’s not. This is a story about the sustained sustainability of an individual who, in truth, none of you are supposed to be reading about. Recidivism, interrupted. A young man who was supposed to disappear once he was behind maximum security walls. A story about someone who was supposed to be all types of things, just not what he became.

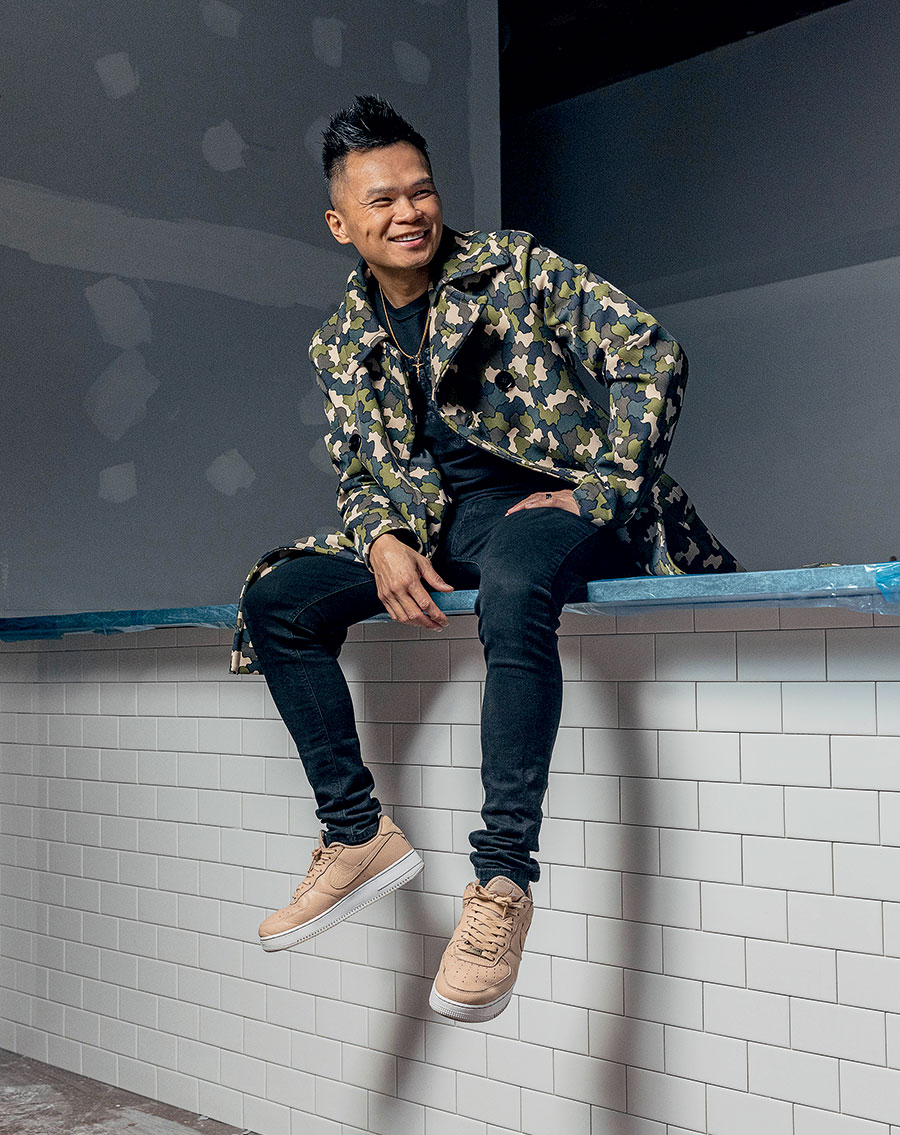

“Do you remember your prison number?” I ask Tuan Huynh, who on this early December day of COVID 2020 was still a senior art director at Leo Burnett. He’d been at the landmark ad agency since 2014, working on such high-profile accounts as McDonald’s, Samsung, Philip Morris, and Kellogg’s, but was now preparing for his departure the following month to focus on his entrepreneurial and activist efforts.

“Yeah, bro — 64215,” he answers. “That’s a number that will never go away. If I go back to jail right now, that’s going to be my prison number. When I’m 80 years old, it’s going to be my number. You never shake that number. But it is a reminder of how far you’ve come.”

Dressed in a black Leaders hoodie, Huynh sits on the couch of his Garfield Park home, where he lives with his wife, Anna, and their two young daughters, and strategizes on how to save Chicago from itself, from the continual molding of little ex-hims. Two years ago, he started an ambitious nonprofit, Chicago Peace, to reach the neglected and forgotten kids of this city through a variety of programs.

As Huynh reflects on his own past — how he had spent 15 and a half years in prison, mostly in an 8-by-5-foot cell in Kansas’s Lansing Correctional Facility, after committing a murder at age 18 — he tells me the story of the lotus.

“The lotus seeds start in the mud at the bottom of the pond. Some seeds remain seeds, while others reach for the surface, reach for a certain level of the water. Some gain leaves once they get to the water’s surface. Then there are some that reach the surface and get sunlight and bloom into the lotus, the most beautiful flower. And once that lotus lives its course, it turns into a seed again and goes back into the ground. You know, some people start in the mud.”

“What set you claim?” It’s a question that has formatted Tuan Huynh’s life, particularly his childhood. “That’s what we all asked each other, anywhere,” he says. “It’s not ‘What’s up, man?’ It’s ‘What set you claiming?’ Because you had to belong to somebody.”

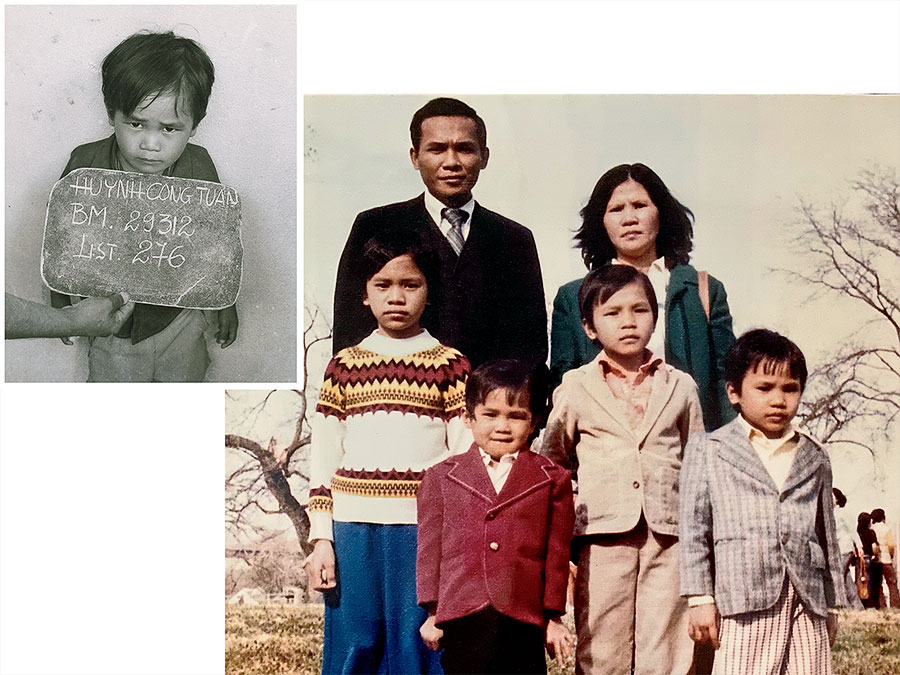

As a kid, Huynh belonged to the streets, the corners, the hideaways, and the concrete of America. A refugee from Vietnam (he came to this country at 3 years old with his family), he grew up in public housing — first in Arlington, Virginia, then in Wichita, Kansas. He witnessed what he calls “the hustle” of America. When your resources are limited, when your value system is compromised systemically, a fend-for-self, survive-or-die, dog-eat-dawg mentality tends to take hold and shape who you become.

“The America I grew up in didn’t really like us,” he says of being Vietnamese. “I grew up in an all-Black neighborhood, but a lot of the Black people didn’t like us. When we went into the Hispanic neighborhoods, they didn’t like us either. They bused us into all-white schools, and those kids definitely didn’t like us.”

So he claimed a set, and a set claimed him. Gang life became his as-one in life. It was like a marriage. They got to know one another, love one another, feed off one another. “My first attempt at selling drugs, I failed,” he tells me, with a hint of a laugh. “You don’t give IOUs to a bunch of crackheads.” So he stole some rims off a car to re-up. He had to learn the game quickly. Survival in America. I ask him how old he was at the time. “Twelve,” he says.

“When I was 14,” he continues, “I made a declaration to myself: I’ma either get rich doing what I’m doing or I’m going to die trying to get there or go to jail for the rest of my life.” He was cliqued up and descending deeper into the gang culture, but Huynh’s enterprise at that age was business, not violence. The plan — excuse me, goal — floating around inside his brain: “I’m going to retire at 18.”

Around 1 a.m., Hunyh got dropped off at his parents’ house. His mother was still up. “She just asked me, ‘Are you hungry?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, I can … I can eat.’ And then she was like, ‘This is probably going to be one of the last meals we will have together, isn’t it?’ ”

But the streets don’t let you go like that. There’s a magnet beneath that concrete. It attaches itself to not only you but your dreams, aspirations, and falsehoods. So instead of working on making his voting-age exit strategy a reality, Huynh began losing himself to the game. Not just claiming sets but orchestrating them.

His leadership qualities at that young age were “a gift and a curse,” according to his childhood friend Viet Doan: “He was a born leader, wasn’t afraid of failing, enjoyed taking risks. Everyone close to him knew he was respectful and always generous with anything. But the thrill of living the fast life and earning and getting a lot of respect was definitely something that changed things for him.”

On February 4, 1996, one month after his 18th birthday, Huynh chose his fate the second he pulled the trigger of a Taurus 9 mm pistol. He’d just left a party at Lan’s Egg Roll restaurant in Wichita. The festivities had broken up after gang signs were flashed, usually an indicator that something is about to jump off. Chronic — as Huynh was called back then — sat in the passenger seat of his homie’s white Honda Accord as they rolled up on the crowd that had just exited the restaurant and was still milling around in the street. Huynh decided to flex in order to break up the throng. So through a partially rolled-down window, he let off three rounds. He claims he wasn’t aiming at anyone in particular and was trying to shoot above the crowd. But one of those bullets struck 20-year-old Charles J. Smith in the head and killed him. Huynh and his crew took off in the Accord.

Around 1 a.m., Huynh got dropped off at his parents’ house. His mother was still up. “She just asked me, ‘Are you hungry?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, I can … I can eat.’ And she started prepping one of my favorite dishes, thit kho. And then she was like, ‘This is probably going to be one of the last meals we will have together, isn’t it?’ ”

Did his mother sense something was up? Not specifically. “She just knew the life I lived back then, that everything is short term. I always called her at least once a week, just to let her know that I was alive.”

A few hours later, detectives were waking Huynh up at his parents’ house with guns in his face, searching his bedroom, where they found four cartridges and a 30-round magazine for a Taurus 9 mm.

He was charged with murder in the first degree. If convicted, he would face a life sentence — likely a hard 40 years behind bars before he got paroled. If he pleaded guilty, though, he’d serve less time — potentially he’d be out in 15 years. But Huynh, still not owning the crime, wanted to go to trial. He wanted to see the faces of those who had turned against him, who had snitched on him. Like his homie driving the Accord that night, who got two years of probation in exchange for singling Huynh out.

Then, while he sat in a room at the courthouse, his lawyer brought in Huynh’s mother, who begged him to take the deal. “In 40 years, you’re going to come home and only be able to trim the grass in front of my grave,” she told him. “But in 15 years, you’ll still be able to take care of me.” Huynh took the deal and took responsibility for the crime he had committed.

And thus was the beginning of the end of the first iteration of Tuan Huynh.

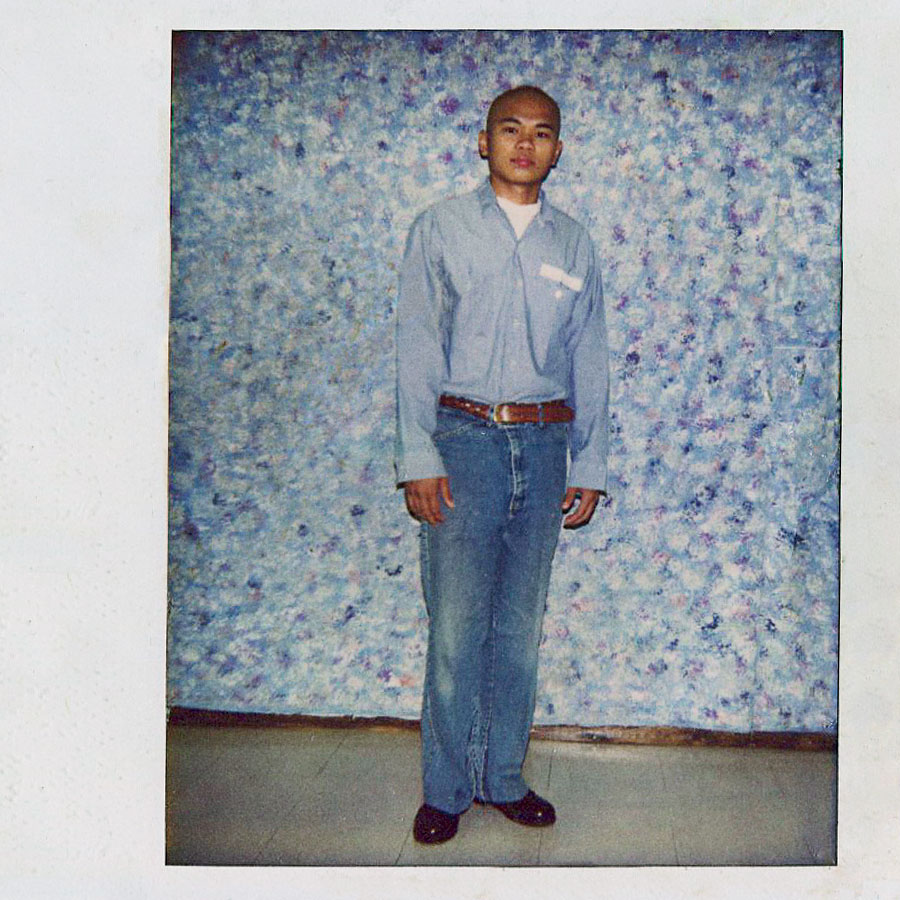

Prison wasn’t a sentence as much as it was an entrance. Stepping into it meant entering a new cold, soulless world of steel bars and beige-painted concrete. To survive inside, Huynh initially just adopted the game he’d been running on the streets. His clout carried. Not that it was all seamless. He got into two major scraps — two fights that put his “little Asian dude” frame (he’s 5-foot-9 and less than 160 pounds) to the test. “I should have died twice in there,” he says.

But it was brain, not brawn, that kept him out of more trouble. Ten years in, he started to change. He began reading more and taking college classes offered in prison and through the mail; he began studying people, viewing them as people, not as threats; and, most important, he picked up a paintbrush, which would prove mightier than the gun he once held. He had always been artistic — it showed in his graffiti and the tattoos he did for friends — but in prison he connected with those skills on a higher level. There, Huynh didn’t fall into art, he sank into it. “It became an outlet for me.”

It became a source of income too. Fellow prisoners, guards, and even the warden started noticing Huynh’s artwork, which sampled Bob Ross’s style. “You couldn’t miss it,” he says with a laugh. “I would have these gigantic paintings in my cell.” Officials at Lansing Correctional Facility began hanging his pieces around the prison. An inmate bought Huynh’s first painting just hours after he finished it, as a birthday present for his daughter. Then other sales followed — to guards, homies, churches. “That’s how I funded school in there,” says Huynh, who earned an associate’s degree in general studies while behind bars.

Huynh also leveraged his pieces to build relationships. Sam Brownback, then a Kansas senator, stayed at that state’s Ellsworth Correctional Facility one night as a PR stunt for a prison program he sponsored. Huynh was incarcerated there at the time. “He saw a painting I did of Jesus carrying a cross, and I ended up giving it to him,” Huynh recalls. After Brownback was elected governor of Kansas in 2010, he hung the piece in the official residence. Huynh would eventually get a chance to see his work displayed there. “Once I got out, he invited me to the mansion to speak.”

While still incarcerated, Huynh started an art education program that graduated around 45 inmates. It, too, was about relationships. “When we commit a crime, one of the first victims is our families — we forget that,” he explains. “Through art, [the inmates] were able to reconnect and make amends, own up to their crimes, and have the remorse that comes afterward. I wanted the guys to focus on that — using art as a piece of the rehabilitation process.”

He also wrote letters. Hundreds of them. Letters to everyone who was impacted by or involved with him being where he was. He wrote apologies to the mayor of Wichita, to the police, to the prosecutors, to the local news outlets, to his family, to the victim’s family, and even to those he felt had turned on him. At the center of all this correspondence, of all these new or rekindled relationships, was his contriteness.

In 2011, around the 15-year mark behind bars, Huynh was asked by the parole board what he planned on doing if he were to be released. Instead of offering the typical BS answers about being a model citizen, he gave them the realest one. “I told them the truth: that I had no idea. I grew up in prison, spent my entire adulthood up to that point in prison. That was what I knew. They just knew I was no longer the same person.”

He was granted parole.

Once out of prison, Huynh, who was 33 by then, sought higher ground. He enrolled in the graphic design program at Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kansas. There he was embraced by a professor, Chaiwat Thumsujarit, who would serve as a teacher not just in class but in Huynh’s reintroduction to unincarcerated life.

Thumsujarit vividly recalls an assignment that spoke to the “determination” he says defines his former student. Huynh created a book that serves as a visual representation of his family’s journey from Vietnam. “Every piece in it is like a thought my father had,” says Huynh. “The notes that are tucked under — he had to keep secret thoughts to keep us alive, you know. The pages turn from white to black, interchanging, to represent the three days and four nights of our journey at sea.” The blurry lettering in one section reflects the sickness that plagued the Malaysian refugee camp where his family stayed and his mother almost died of pneumonia. Thumsujarit sees the project as an interpretation of how hope fades but is still necessary for survival, and the power of it sticks with him to this day.

While at Fort Hays State, Huynh also performed simple acts of kindness. Thumsujarit remembers him cutting fellow students’ hair in the dorm hallways and doing the same for residents of a local nursing home. “When he gets to a certain point, he’s able to really stand by himself,” Thumsujarit says. “Like a tree that can grow on its own, he doesn’t need water to grow because the root of the tree is deep down in the ground now and it can find its own water.”

Huynh was also finding a new set: a family of his own. A couple of weeks after his release from prison, he met Anna Shelter, whose mother ran the inmate seminars on leadership and fellowship he’d attended. They married the following year.

When he graduated in the spring of 2014, Huynh had several job offers. But Chicago seemed to “call” him, he says — specifically, an offer from Leo Burnett, which recruited at Fort Hays State. Huynh had just finished watching the CNN docuseries Chicagoland and was struck by the number of shootings in the city. “I thought we could do some good here.”

But Burnett’s offer was for an internship, not a permanent job. “I turned them down,” he says. “I told them, ‘I can’t take it. I’m too old to be interning.’ That was on a Friday, and they said, ‘Give us until Monday.’ On Saturday they called me and offered me an art director position.”

It was then that Huynh let the agency know he wasn’t going to pass the background check. Next came the “Hold up, the clients might not be comfortable with that” call. And for the two weeks that he waited on the agency to figure out what to do, he and Anna were essentially homeless, living out of their car and couch surfing. Finally, Huynh got word that the job was still his.

He was no charity case, says Kerri Soukup, an executive creative director at Leo Burnett, who was integral in bringing Huynh on. “I attended a recruiting trip that year with another FHSU alum, and Tuan was one of our top picks. I had given Tuan feedback during the critique of his work, and he very quickly followed up with an email that showed how well he internalized it and came up with fresh solves and executions. That really helped show me his heart and hustle and ability to take feedback. Plus, that work was really smart and well done — still one of my favorite student projects. I even share it with other aspiring design students as an example of conceptual thinking and excellent craft.”

Huynh’s skills were never a question. Soukup just needed convincing about him as a person. “After I spoke with Tuan and learned more about his felony, prison time, and past, I spoke to the professors. They spoke so highly of his character, work ethic, and integrity. His rights as a citizen had been restored, so I felt he deserved a chance, based on his talent and all the work he was putting into reforming. From there, it really took legal counsel, the [chief creative officer], and CEO all agreeing that they would support this decision.”

Michelle Mahoney, the agency’s director of social impact, recalls meeting Huynh for the first time shortly after he was hired. “He raised his hand to lead a team, and his dedication toward helping our nonprofit partners never changed. He leads with purpose and is truly committed to making a difference every day.”

Those words: hustle, heart, lead, purpose. They are constants for Huynh now.

Ryan J. Brown, one of Huynh’s protégés, goes further: “I’ll use the word ‘resilience.’ That’s the keyword to Tuan’s whole life. At Burnett, he was resilient in how he pushed for progress. When it came to being responsible in advertising, he was never going to let anyone shoot a campaign that he knew was wrong or misrepresentative. He’s going to be resilient in making sure that things are done right and exact.” In 2019, Huynh partnered with Brown to start Naomi Burnett, a team within Leo Burnett aimed at ensuring that the agency’s campaigns are culturally sensitive.

“Tuan is one of the few champions within the industry that understands the hurdles that we [as people of color] have,” Brown continues. “And not just the hurdles once we get inside. Tuan understands the life hurdles. He understands being a felon and trying to get a job, which is a whole part of America that corporate America doesn’t understand. He understands being a young person with no guidance and navigating out of street life. He understands being an immigrant and coming over, learning a new language. So it’s like all of these experiences he’s had are what makes him that resident champion for causes and people.”

Huynh was relentless in that effort at Leo Burnett. He started an unofficial fellowship program called Tuan’s Kids, bringing youth in for tours and mentoring on his lunch breaks. “I did it on the fly, didn’t ask for permission,” he says. That morphed into a more structured program called Leo’s Vision. He also spearheaded the Pencil Project, a college scholarship program for students whose art demonstrates they are “the difference that makes a difference,” as Huynh puts it. Outside of work, he helped get True Chicago, an organization that connects young Black and brown creatives with professionals in a variety of fields, up and running and served on its board.

“Tuan is one of the few champions within the [advertising] industry that understands the hurdles that we [as people of color] have.”

In 2019, StreetWise included Huynh in its list of the most influential Chicagoans, noting that “his work in the arena of diversity and inclusion is tireless and expansive.” That same year, Newcity crowned him “best Chicago-made activist.” It wrote: “Huynh dedicates every available minute to helping others through endeavors of his own and those in his periphery.”

Then, in January 2021, in a power move that could be looked at as part visionary ingenuity, part stepping out on pure faith, part arrogant bet on himself, Huynh resigned from Burnett after nearly seven years. He left to find further freedom in a slew of projects: launching a Vietnamese coffee brand, VietFive; reinvesting himself in Captrue, the creative and cultural consulting business he started; and immersing himself more fully in activism through Chicago Peace, which might end up the most impactful of his ventures.

As Thumsujarit says, this is how trees grow. They find their own water.

I ask the professor if there is a pride he carries knowing that Huynh was once one of his students. “What makes me proudest is how he inspires other people. Some people are just about the business, but he inspires people, like: ‘I’m not giving up. I just tried my best but I’m going to try one more time.’ People like him make teachers want to teach forever.”

How rare is this situation? This story? This soaring rise from the depths of prison? Let’s start here: A 2018 study by the Prison Policy Initiative, a think tank and advocacy group, found that people who were once incarcerated are unemployed at a rate of over 27 percent — “higher than the total U.S. unemployment rate during any historical period, including the Great Depression,” the report noted. Then there are these figures from the U.S. Justice Department: 71 percent of inmates released in 2012 were rearrested within five years; 46 percent returned to prison. Based on the numbers, it’s no lock that Huynh would even stay free, let alone survive a bid inside the C-suites on the mean streets of upper Wacker Drive.

“I’m still bound. Because of what I did, those things are always going to hang over my life. There are still doors closed to me.”

In a recent Sports Illustrated article, Larry Miller, the former president and now chairman of the Michael Jordan brand at Nike, disclosed, after decades of secrecy, that he’d spent his late teens and 20s in prison after committing a murder at age 16. I asked him just how hard it is for people like him and Huynh to put their pasts behind them and thrive. “It is rare for many people with similar backgrounds, where time spent in prison is a part of that person’s foundation, to not fall victim to the societal and corporate pitfalls of getting caught up in some of the same activities and behaviors that used to be a large part of their lives,” he told me over email. “From my personal experience I can honestly say that progressing and advancing in a corporate space while having a criminal background can be very difficult.”

Difficult, but not impossible. Days after his departure from Burnett, Huynh and I ride to Bridgeport to pick up a small U-Haul van. He’s using it to move an antique Ferla coffee cart that will be the centerpiece of a pop-up he’s putting together inside 88 Marketplace, a Chinese supermarket in East Pilsen. The plan is for this to be a springboard to a brick-and-mortar coffee shop in the West Loop. Our conversation about the political polarization that plagues America, the Stop Asian Hate movement (Huynh has been one of its most vocal local organizers), and Jeremy Lin being blackballed by the NBA takes a turn when Huynh says something that puts the totality of the last 25 years of his life — prison, Leo Burnett, newfound independence — into perspective: “Equality to me in America is a myth, a false narrative. So my purpose: I want to provide equity.” His past no longer lies in wait; he is a man living by faith, no longer fear.

Yet it’s demon versus demons. They are fighting inside of Huynh’s soul. The violence against Asians is internally fucking with him. His other cheek is on fire from constantly turning it. The God in him keeps him calm; the Tuan in him struggles with not retaliating. But even before that, something had been battling inside him. The demons (plural) are his past, his behaviors and crimes — he knows the reality that he may never be truly free of them. The demon (singular) is the person he once was who still rests in him. “Love conquers all wrong” is what he keeps saying to himself. But at times, he has to stop and ask if that is really true.

At Base Cafe in the Bridgeport Art Center, while we wait on Seoul Taco owner David Choi, a friend of Huynh’s, to join us, I ask Huynh a question: “What is the difference between being free and finding freedom?” He adjusts his limited-edition White Sox gray mesh snapback cap as he looks at me without saying anything. Anything. The cap adjust says it all: Ask the question you really want to ask, bro. I rephrase: “To you, is there a difference is what I’m asking.” His answer becomes the summation of his existence.

“I think there is a difference,” he says. “Because for me being free is to be able to express myself completely, whole, unadulterated. That’s in creativity and how I build relationships with people, how I create and how I do business, but also how I’m able to give freely. But with freedom I’m still trying to find myself. Because, truthfully, I still can’t be who I want to be. There’s a part of my past that I’m still bound by. Like, I can’t even get life insurance, bro. I tried to buy life insurance outside of Leo Burnett, and I got denied because I wasn’t 10 years off paper on my parole. I can’t rent in the city because of my record. There are still countries I can’t travel to. I was detained in Canada twice. One time because I wanted to take a picture on the other side of Detroit, a sunrise shot on the other side of the bridge to see downtown Detroit. They detained my butt four hours. The other time I was going to Amsterdam, just switching flights in Toronto. Detained me for eight hours. Threatened to keep me in prison until I got to immigration court. Australia won’t accept me, ever. Yeah, G, that’s real.

“So I’m still bound. Because of what I did, those things are always going to hang over my life. There are still doors closed to me. As successful as I may be — and granted, I am more successful than a lot of my people who’ve walked in similar footsteps — I’m always going to be reminded. Always. Constantly. I shared my story recently, just a week ago, to a room of people who are supposed to be supporters of mine and what we’re doing, and there’s always that 1 percent who feel uncomfortable, who don’t even want to shake my hand.” He pauses. “Just turned away, didn’t even want to acknowledge me, bro. Yeah.”

Later his phone buzzes. It’s Binh Ly, an inmate Huynh befriended while both were at Lansing. He’s calling to update Huynh on his latest parole hearing and to thank him for being him. The impact a former inmate like Huynh can have on current ones deepens once the possibility of their release, their second chance, nears. Their conversation is brief. The smile on Huynh’s face is evident, even through his black KN95 mask. It’s a moving moment, one rarely seen when it isn’t scripted: one man being the direct line of hope for another so that he won’t continue to be the man he once was. In life, we call that change. Not everyone can do it.

“Here’s what I learned about forgiveness,” Huynh tells me in his typical soft-spoken yet passionate tone. “I learned it from Diary of a Mad Black Woman [note that Huynh may be the only person ever to learn something from a Tyler Perry movie], when the grandmother said, ‘True forgiveness is when you look at that individual that’s wronged you and has sinned against you, and that sin is the last thing you think about.’ That’s true forgiveness. And I learned that, man. I learned that in my heart. I can’t control people’s …” He trails off. “When they see me, even if they know my story, I feel that the first thing they think about is the crime that I did.”

It is then that I realize Tuan Huynh’s life story remains coerced by two questions: Should any of us be defined by the worst thing we’ve ever done? And can redemption exist without forgiveness?

I don’t respond in that moment. But a few days later, when we reconnect, I do. “Forgiveness,” I say to him, “is unlocking the door to set someone free and realizing you were the prisoner.”

Human Being 64215 gives me a fist bump.

I will not follow where the path may lead, but I will go where there is no path, and I will leave a trail.

Tuan Huynh so embodies the opening line of Muriel Strode’s 1903 poem “Wind-Wafted Wild Flowers” that you almost believe she had him in mind when she penned it. A Vietnamese refugee dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in America, a good-for-nothing felon who has lost 23 homies in the last 10 years, survives every demon only to become prevailer, outlier, endurer, enlightened wildflower. The one who decides to leave a trail.

I am life’s mystery, — and I alone am its solution.

I am the dreamer of dreams, — and I am dreams come true.

I am the supplicant, — and I am the god that answers prayers.

The mud, the struggle, the contradiction, the triplicity, the absolution, the come-to-truth of dreams, the no path to path, the no way to way, the lotus, the wildflower. All him.

It’s midday on August 28, 2021. Huynh is standing on a stage outside the DuSable Museum as Chicago Peace Week, organized by his nonprofit Chicago Peace, comes to an end. Over the last few days, the organization, working with the city and various sponsors — including, Amazon, Target, Leo Burnett, and BlueCross BlueShield of Illinois — has put on a series of student workshops at three public elementary schools around town, focusing on everything from mural painting and school-beautification upgrades to engineering and entrepreneurship. Chance the Rapper’s youth empowerment charity SocialWorks even held “state of mind” mental health sessions.

Following the morning’s Peace Walk, the Peace Festival at DuSable was supposed to be the grand finale of Huynh’s independent opus. Unfortunately, he is speaking to an almost empty field of grass in Washington Park. As fate would have it, the culmination of arguably the most important project of his post-Burnett career comes in the form of an outdoor event on one of the hottest, most humid days of the year. There’s disappointment in Huynh’s face but not discouragement. This is his first time putting on an event of this size and scope, and the rest of Peace Week was considerably better attended.

Huynh’s life story remains coerced by two questions: Should any of us be defined by the worst thing we’ve done? And can redemption exist without forgiveness?

Huynh connects the unseen dots on the historical significance of this day. “This is the date of Emmett Till’s murder in 1955, the date of the anti–Vietnam War protest that took place during the Democratic National Convention here in 1968,” he points out to me. It is also the date MLK gave his “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963 and when Britain abolished the slave trade in 1833.

It is here, in Washington Park, that Tuan Huynh is at his apotheosis, at 43 years old, standing on a stage, trying to save a city from within, from the concrete up. Students were supposed to be here to experience his vision and community investment. Their parents and family members were supposed to be here to witness Huynh’s “equity” in action, to see this living embodiment of reform, resurrection, and human hope.

But even if they were in attendance, how many would know Huynh’s story? About how God repurposed him. All they’d see is a “little Asian dude” who kinda dresses like them, kinda talks like them, telling them how important their lives are — not how important his journey and his resolve are to them. I laugh to myself, thinking about what those not here are missing. If they only knew how this man is breathing evidence that redemption is real and that life most often is a sprint, not a marathon. One long-ass 26.2-mile sprint.