The Believer

Natalya Zavizistup, 45, Near West Side

In February, my horoscope showed a big danger in my city of Kharkiv. I decided to come to Chicago and spend my birthday with my son, who studies at UIC. Now I believe that protected me from war.

While I stay here under temporary protected status, my 84-year-old father refuses to join me. He is trying to survive winter while he teaches online classes at Kharkiv National University of Radio Electronics. He lives alone, has health problems, and his apartment doesn’t have enough heat. It’s so hard to choose between protecting my life and going back and caring for him. Every day I call him and wonder if this may be our last conversation. Friends have told me that when they drive or wait at a bus stop, they never know where the bombs may fall.

When I was little, my grandmother used to tell me stories from World War II. It was so strange to hear about hunger and destruction. Now I see it in our times, and each morning I hope to realize that this is just a bad dream.

“Each morning I hope to realize that this is just a bad dream.”

I’ve always thought it must be so cool to live and work in America, make a lot of money, have a nice house and maybe two cars. Now that I am here not by choice but by necessity, that has all changed. When I see images of destroyed flats in my hometown that people spent years building, I realize that material things are not important. I live in this beautiful city with big buildings, museums, amazing architecture, but my heart stays in Kharkiv.

I got my work permit in early December, so now I work at the Selfreliance Association; it gives me joy and pride to help fellow Ukrainians start their new life in Chicago. Recently, I started painting again. I paint flowers in watercolor. It puts me in a good emotional state. Though I don’t know what the future will bring, I try to be positive.

The Student

Oleh,* 21, Ukrainian Village

There had been talk about Russia invading since that January. Some of my fellow university students in Lviv would even bet on when it was going to happen. It put psychological pressure on us, but we kept living our lives. Few took threats of war seriously.

That day, I woke up at 8 a.m. and checked my phone, and the first thing I saw was that my ticket to Slovakia was canceled. In two days I was to head there as an exchange student for the final months of my studies in web development and economics. Then I turned on the TV and saw images of rockets hitting Ukrainian cities.

In the following days, thousands of people from across Ukraine started arriving in my city, which is 50 miles from the border with Poland. Schools and other institutions were crowded with those seeking shelter. Then in March, my area was hit for the first time. We’d have air alarms several times a night for a week, then it would be quiet for weeks.

“We’d have air alarms several times a night for a week.”

That month, border authorities allowed students enrolled in a foreign university to leave the country. Finally, I was able to go to Slovakia with my mom. By the time I graduated in June, her sister, who lives in Chicago, had told us of a new program from the American government called Uniting for Ukraine, for displaced Ukrainians.

We arrived in Chicago in July. For the first week, I was looking for tickets to go back to Slovakia. Little by little, I adapted and it got easier. But I think I would prefer to live in the suburbs, where it’s quieter. I have been volunteering at the Selfreliance Association, an agency that helps newly arrived Ukrainians. I fix problems related to IT, manage the website, and help translate for various institutions who come here to assist. Uniting for Ukraine is a good program, but some participants wait for over six months for their work authorization. Without it, they cannot support themselves and their families. That includes me. My dream is to work as a web developer. Then I could make donations to my country.

*Oleh asked that his last name not be used “for security reasons.”

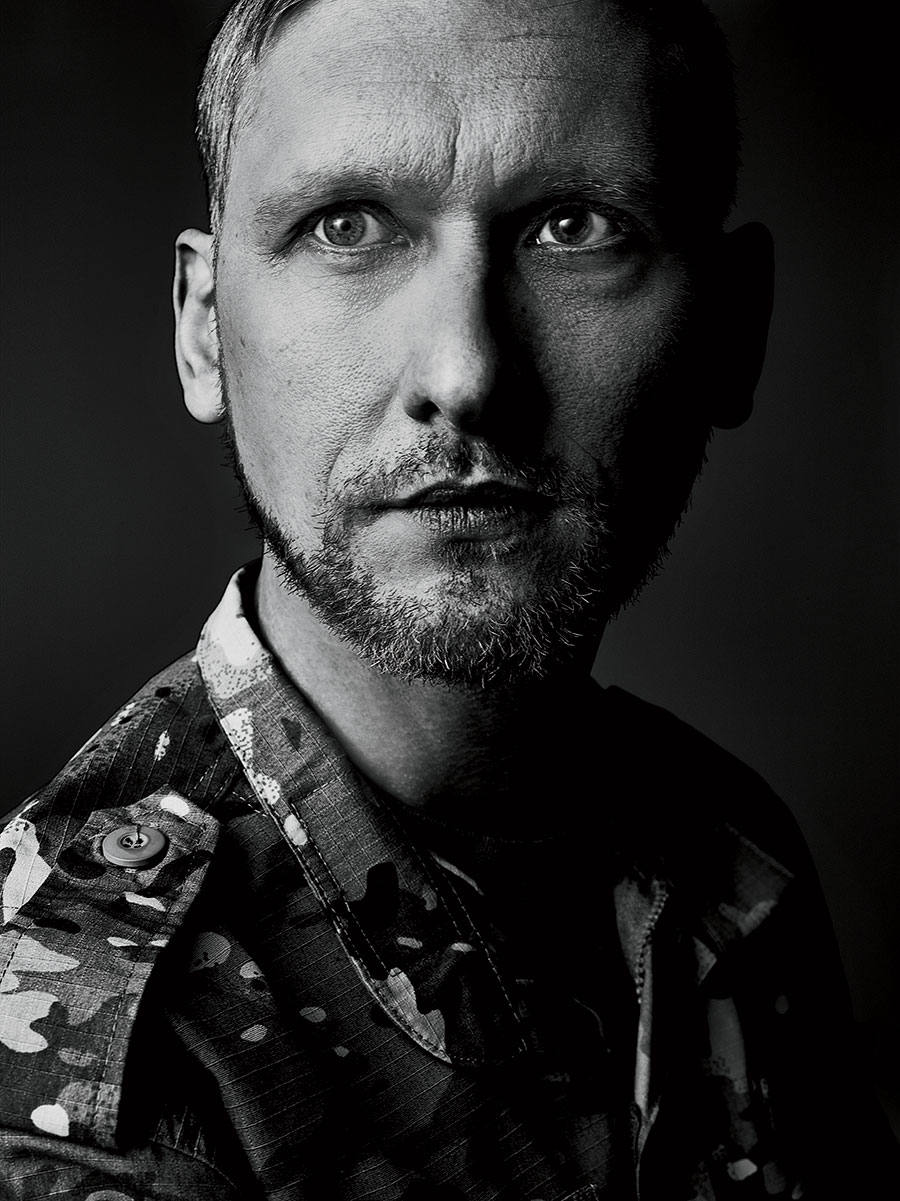

The Soldier

Serge Senik, 44, Bannockburn

On February 24, I was on my way to Zurich for a job for my private investigation business. My wife called me from Kharkiv and stuck her phone out the window so I could hear the explosions. I immediately turned back.

I’m a senior lieutenant and pararescue jumper in the Ukrainian Air Force, and my job is to recover and evacuate injured Ukrainian pilots in occupied territory. During one of these operations in central Ukraine, I was injured in a missile explosion. I was one of only two in my unit who survived. Being alive when your friends are dying next to you is even scarier than dying. I consider myself very lucky that I was found and rescued, though I have no memory of how long I was down there under concrete debris, waiting to die.

“I was one of only two in my unit who survived.”

My right knee was torn, my left shoulder was ripped apart. I underwent two surgeries in Europe. A friend from high school I hadn’t seen in 25 years, who runs Wellness Club, a physical therapy clinic in Bannockburn, Illinois, found out I was wounded. It took her a couple of months, but in September she finally persuaded me to come to America on a medical visa for rehabilitation, with the help of Revived Soldiers Ukraine. She works with me daily, but despite that, another surgery on my shoulder may be needed.

While I undergo treatments, my wife and two children are in Poland. I’m counting down the days until I can pick up weapons and return to service. I feel guilty that my teammates are there while I am here. Sometimes I feel like I betrayed them.

If it weren’t for the military support of the United States and the European Union, there would be no Ukraine by now, even though we would fight until the very end. We are thankful, but we need more. Only the authority of NATO and closing the sky above Ukraine could send the right message to Russia to stop the war. Americans must understand that the defeat of Ukraine would lead to Russian expansion into Europe, maybe even a world war.

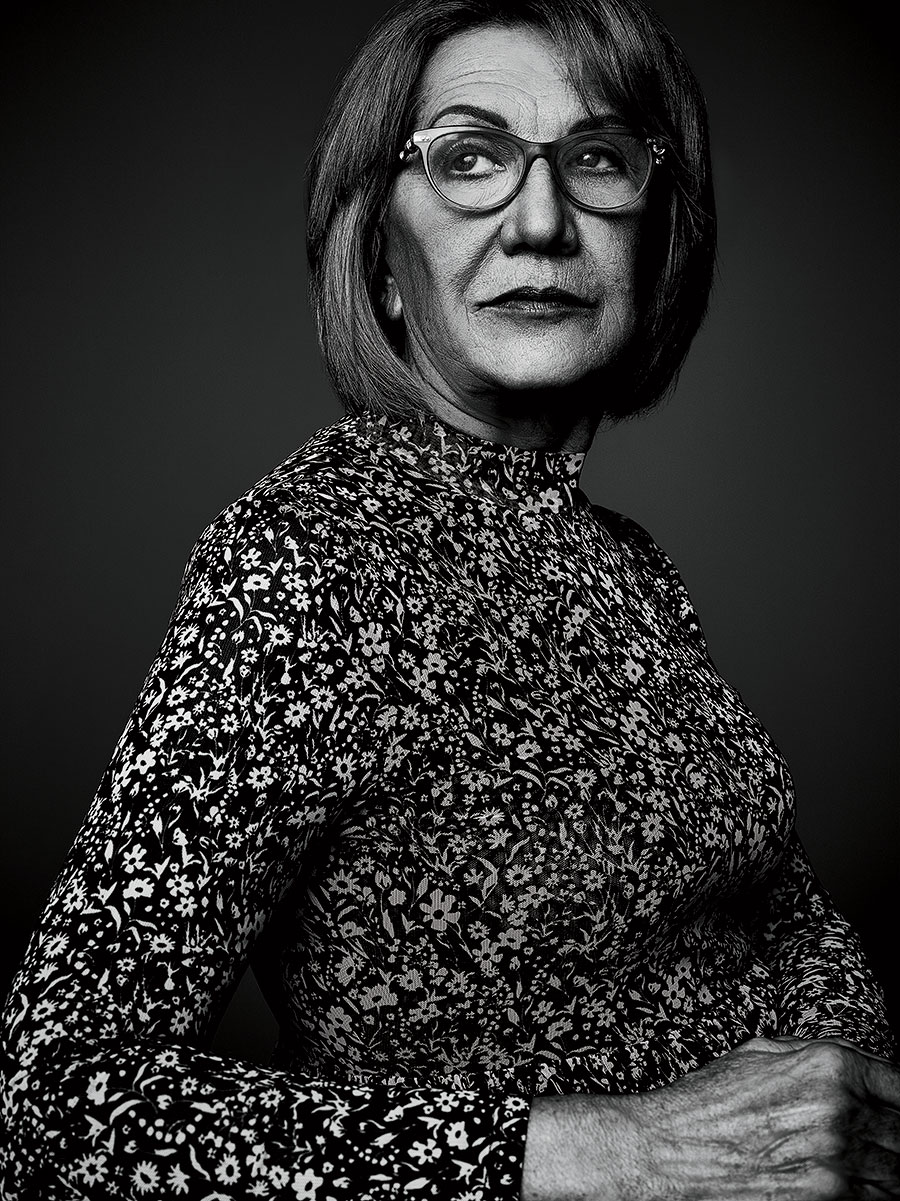

The Retiree

Valentyna Averkova, 65, Humboldt Park

I had a good life. For 34 years, I was a chief technologist at the tannery in Voznesensk, a small town in southern Ukraine known all over Europe for its leather goods. I had a beautiful house with a garden full of roses and a nice car. I enjoyed my retirement.

When I heard explosions in the distance, I was in disbelief. We all thought it would be over in a few days. Instead, war became closer and more real. Voznesensk was strategic to the Russians because of its bridge on the way to a nuclear plant. When our army destroyed that bridge to cut off their path, Russians started firing into my town from tanks. They hit my brother’s house. Luckily, no one was there. My son, who has lived in Chicago the last three years, told me I could not stay there any longer.

“I miss everything — my house, my friends and relatives, my language, my hairstylist.”

So I took a small backpack and a friend with her pregnant daughter and another child and drove to Lviv. I crossed the border to Poland, but there were no appointments available at the U.S. consulate for the rest of the year to get a visa. I flew to Spain, then Mexico City, then Tijuana, where church volunteers helped Ukrainians like me enter the U.S. on humanitarian parole. I traveled alone, sometimes didn’t understand the language, but I met so many kind and helpful people to whom I will always be grateful. By mid-April, I was in Chicago.

Though I am happy to be with my son, life in America is very different. Chicago is such a big city. At first, I cried all the time. I miss everything — my house, my friends and relatives, my language, my hairstylist. I am learning English at Wright College Humboldt Park, but it is so hard to remember new words. I tried working as a cleaning lady, but it was very challenging, physically and mentally. So now I spend my days walking around Chicago. I’ve discovered charming streets. Maybe one day, when there is victory, I will return to Ukraine.

The Mother

Khrystyna Hrytsenko, 33, Gurnee

At 5 a.m., I woke up my son with words I never thought I’d say: “David, the war has started.” We had just one hour to pack. David took three toys. I opened the windows to our apartment in Irpin and heard the explosions. There was already panic in the streets. People ran to their cars, to stores, to gas stations. I remember thinking, Will they shoot us on the way?

Just 10 days earlier, we celebrated David’s eighth birthday. My husband worked for a building company, so I could afford to stay at home. We had a good life and big plans for the future in Ukraine. I thought our country was going in the right direction.

“I remember thinking, Will they shoot us on the way?”

We drove to Lviv, where my parents live. Over the next few days, I heard stories of what was happening in Irpin and nearby Bucha to the people who couldn’t leave. Our towns were shelled. The bridge was bombed. There were Russians in the streets, shooting at cars with children in them. In the evenings, they were drunk and went from house to house looking for women. One of David’s friends died as she tried to leave with her parents. It felt like a Hollywood movie. After a week in Lviv, we decided to go to Poland.

Irpin was liberated at the end of March, and on my birthday, May 17, we returned. I was happy to be home, but I was scared all the time. I cried, couldn’t sleep, and started having panic attacks. On the playground, there were still pieces of glass. Then Putin started talking about a nuclear bomb. I told my husband, “Please, take me away from here.”

Just when I thought about going back to Poland, my aunt, who lives in the Chicago area, applied for us to come under the Uniting for Ukraine program. We arrived in August. I believe this is the best place for us right now. Not only are we safe, but we can speak out about Ukraine and call other countries’ attention to it. I do it through singing traditional songs at Ukrainian events. I used to sing a little in Ukraine, but now I have this sea of emotions that need an outlet. The world must hear our voices.