Calling Chuck Todd, 42, a political junkie is like calling Rahm Emanuel a control freak. While Todd’s latest platform, NBC’s Meet the Press, remains stuck in third place against its Sunday morning rivals, my hunch is that Todd, NBC news political director since 2007, will catch on by virtue of his knowing every detail and stat of domestic politics.

He brings all of that to bear in his just-published Obama bio, The Stranger: Barack Obama in the White House. His chapter notes list by name just a few Obama staffers whom he interviewed, none of them the Chicagoans who figure so largely in these pages: Rahm, David Axelrod, Valerie Jarrett, Bill Daley). A citation "interview sources" indicates to me that some of the aforementioned likely talked to Todd, but not for attribution.

"Not so secretly," Todd writes about Rahm Emanuel’s tenure as Obama’s Chief of Staff, "Rahm hated the job." He had succumbed reluctantly to the President-elect’s entreaties that he give up his congressional seat to take the COS job. Emanuel desperately wanted to be the first Jewish Speaker of the House; he had, Todd writes, "barely concealed designs on [Nancy] Pelosi’s speakership."

For Rahm, West Wing life wasn’t happy. He recognized that Obama, who tried, in a sense, to be his own COS—a possibility in the Senate, but an impossibility in the presidency with its massive number of moving parts—"had regularly encouraged others to go around the COS…He didn’t see his sphere of influence within the White House expanding," He had become "frustrated by what he saw as the President’s inability to centralize internal power," not to mention Obama’s insistence on tackling national health care when Rahm knew that the ACA would be big trouble. He tried repeatedly and unsuccessfully to persuade the President to tackle financial reform first.

Rahm was both bored and offended by Obama’s attempts to regulate him. He disliked having to listen to criticism that he "fought too much with his coworkers," that the White House had become a "sexist boys club," and that Rahm “didn’t get along well with senior female members of the staff, Valerie Jarrett first and foremost among them.” Todd reports, in Rahm’s defense, that the COS was known to scream as much at men as women. "…he didn’t care…about the gender of the person on the other end of a 'fuck you,'…"

When Rich Daley announced he was done being mayor, it took Rahm "about a minute," Todd writes, to announce he was heading back to Chicago, to win a job that he "coveted" almost as much as Pelosi’s speakership.

In Todd’s entertaining, enlightening portrayal, Rahm emerges as a man who cares most of all about one thing: winning. Todd describes Rahm as arguing repeatedly against sending Obama to campaign for any candidate, no matter how far out on a limb he/she had gone to support the President on tough votes, if that candidate was likely to lose. “Appearing with a loser,” Rahm argued, "…only made Obama look weak…Why waste the political capital?"

For all Rahm’s harsh edges, he comes off as the most valuable player in this West Wing drama. Todd reports that Obama and Rahm recognized before the 2009 inauguration that the CIA wasn’t acting forcefully enough to capture/kill Osama bin Laden. Thereafter, then CIA chief Leon Panetta "would travel [once a month] to the White House to brief Obama specifically on the hunt…Emanuel made sure Obama had 45 minutes blocked out every month for a meeting about bin Laden—a further sign to the intelligence community…of the President’s priorities."

Todd writes that Rahm also recognized, after a status meeting in his office, in October 2010, that then HHS secretary Kathleen Sebelius was not up to the job of administering, engineering, and launching the ACA. As Sebelius left Rahm’s office, "the cold-blooded operator that is Emanuel had wondered aloud whether Sebelius was up to the task."

David Axelrod, Obama’s first-term chief messaging guru and strategist comes off in Todd’s telling as a more a soulful type who believed, unlike Rahm, who comes off as almost insanely pragmatic, that Obama needed to keep his campaign promises and abide by the values he brought with him to the White House.

Todd describes an Oval Office meeting on the ACA, in which Obama "stopped a debate between Emanuel…and Axelrod, who retained a sense of purity about the president he had helped elect…"

Axelrod: "One of the problems is, we’ve made all these deals…We used to attack the insurance companies, and now we’re making deals with them."

Emanuel: "We decided to make these deals because we wanted to pass a bill."

Unlike Rahm, who retains strong ties to both Barack Obama and the Clintons, Axelrod’s loyalties were strictly to the Obamas. Todd notes that Axelrod (and press secretary Robert Gibbs, another hyper-Obama-loyalist) opposed the selection of Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State. When Obama’s senior advisors, including Axelrod, made a pilgrimage to Harlem to meet with Bill Clinton and try to salve some of the primary campaign wounds, an unidentified person in the room told Todd that Bill Clinton obviously "was uncomfortable with [Axelrod’s] presence…. Clinton wouldn’t even make eye contact with Axelrod."

And then there’s Valerie Jarrett. Getting on Jarrett’s bad side, not bothering to hide his disdain for her abilities, Todd writes, was not a smart move for Rahm. Jarrett was the "first friend…the one person who knew Obama before he was Obama…" Todd notes that Axelrod also didn’t think "well" of Jarrett and had "run- ins" with her but could "hide his annoyance better than Rahm or…Robert Gibbs." Both Gibbs and Emanuel, Todd reports, believed that Jarrett failed at one of her assigned responsibilities—"building relationships with the business community…They didn’t get why she didn’t pay a price." (The answer, as many other writers, including this one, have noted before is that Valerie and Michelle are close friends, and the President didn’t dare cross Michelle; from the start of their marriage, she wanted her husband to make big bucks at a law firm and not pursue the seemingly impossible goal of becoming president.)

It was Axelrod and Emanuel, Todd writes, who pushed for Bill Daley to take Rahm’s place as COS. But "almost from beginning, Daley proved a poor fit." Obama and Rahm weren’t close personally, but they shared enough to form a bond. Daley and Obama did not know each other in any depth and, Todd writes, "the two had little real rapport." Also Daley was skeptical from the get-go that he would succeed as COS because he inherited his staff—he was allowed to bring only one person with him—and "wondered just how much power he would have over a staff someone else had built." The staff, especially the younger people, were miffed that Daley canceled the regular 8:30 morning meeting that gave junior staffers an opportunity to learn and to show their stuff. They found Daley "cold and corporate." Outside the White House, Daley’s relations with top democrats such as Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid were almost as toxic as his relations with Republicans—Speaker John Boehner, for instance. In other words, Daley didn’t have much to offer the President and the President didn’t have much to offer Daley.

The two men had an understanding that Daley would stay as COS through the 2012 reelection; Daley left having served barely a year when, in the summer of 2011, "it became clear that he wouldn’t have a major role in crafting the campaign…"

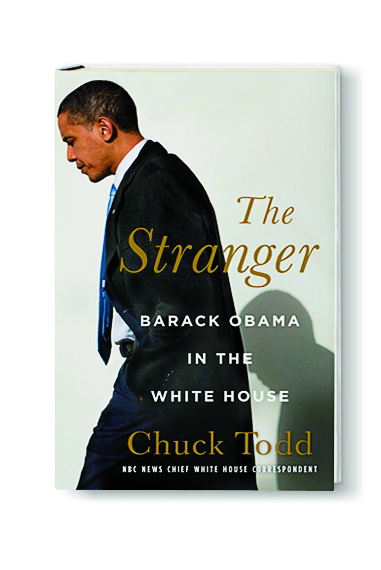

Last September President Obama gave Todd a sit-down interview for his debut as Meet the Press moderator. (That was the one and only time that Todd topped the ratings.) There probably won’t be a sequel any time soon. Obama Inc. is reportedly not happy with the CEO’s portrayal in The Stranger. No one in the Obama camp could be happy with the cover photo, which shows a slouching, downcast, peeved—his expression suggests acid reflux—President. While that guy makes many appearances in the book, so does the highly intelligent, articulate man who managed against some steep odds to rise from an unmemorable, short stay in the U.S. Senate to win the nation’s office not once, but twice.