|

|

|

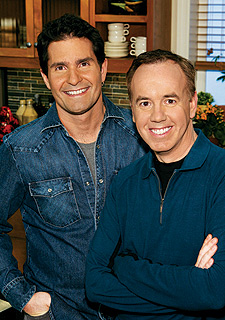

There is some drama in the kitchen, and it has to do with the mushroom-hazelnut pâté. “It doesn’t look right,” says Steve McDonagh. We are in the studio of the food photographer Laurie Proffitt, and standing around the kitchen island are Proffitt, the food stylist Josephine Orba, the book designer Susi Oberhelman, McDonagh, and the chef Dan Smith. Together McDonagh, 42, and Smith, 44, are the Hearty Boys: caterers, restaurateurs, hosts of a TV show on the Food Network, and-if things go right here-authors of a cookbook due out in September. Smith is the taller one with the beefcake looks; McDonagh has the friendly face and quicker wit. both of them have gleaming white TV-perfect smiles.

|

But right now the pâté looks strange. It’s a neat little loaf, but it isn’t photographing well. Orba has tried many different approaches: slicing it into squares and stacking each square on a cracker; crumbling it into chunks that fall off the loaf; scooping a helping of it onto a wooden serving spoon. But so far, the pâté, which tastes amazing, cannot be captured in an appealing photograph. Crumbled or sliced, it looks dense and gray, like a disintegrating marble or a patch of carpeting.

—

“Maybe it’s the crackers,” says McDonagh. “Maybe we need handmade crackers.”

Silence. Obviously, no handmade crackers are in the house. “How many pâté loaves do we have?” asks Orba.

“I made four,” says Smith, “so we have two left.”

The moment perplexes in part because the photo shoot has gone beautifully so far. The skewered pork roulade with roasted tomato cream looked moist and inviting. The smoked salmon canapés with orange butter and capers had a certain whimsy, thanks to Orba’s orange peel curlicues on top. Ham on Cheddar shortbread, chocolate cream cheese cupcakes, glazed duck with Provençal olive tartine-all perfectly mouthwatering.

While Proffitt changes the light filters, Smith and McDonagh take a break, sitting down to chat about the swirl of professional activity around them these days. For almost ten years, the Hearty Boys have been dishing it out to Chicagoans: first as a catering business, then with a takeout gourmet business, then at their restaurant, HB, on Halsted in the heart of Boys’ Town. There is the upcoming cookbook, Talk with Your Mouth Full, being published by Stewart, Tabori & Chang in the fall of 2007.

“And in the spring, we will be opening a new restaurant on Broadway,” says McDonagh. “The name will be Frill, as in frill pick,” those toothpicks with tasseled ends used on canapés, “and it will be an all hors d’oeuvres restaurant.”

“We were going to call it Hors d’Oeuvres,” says Smith, “but we figured no one could spell it.”

—

Still, even with all their ongoing ventures, Smith and McDonagh probably remain most excited about something that happened a year ago-winning a food competition called The Next Food Network Star on the cable television Food Network. The victory gave them their own 30-minute show, Party Line with the Hearty Boys, which began airing in September 2005 and took their cooking and entertainment ideas into households every Sunday morning; it also made them the first gay couple to have a TV series. (Last year, The Advocate, a national gay magazine, asked the question, “What took so long?”)

“We couldn’t be happier,” says Smith.

|

That’s good, because not everyone is impressed. In a recent article called “TV Dinners: The Rise of Food Television” in The New Yorker, Bill Buford, a best-selling author, wrote that the Hearty Boys had “an anachronistic, almost blithely oblivious aesthetic: their meals seem like something someone’s parents once ate, a campy ‘Joy of Cooking,’ or a display at a MOMA exhibit.”

“Oh, yeah, we saw the article,” says Smith with a laugh. “Our first reaction was, Do you know what ‘anachronistic’ means?”

“I guess that’s true,” says McDonagh, but he doesn’t sound convinced.

Certainly, some of the food Smith and McDonagh have done on their television show-pigs in blankets with curried ketchup, a veggie basket with ranch dip, homemade lollipops encasing gummi worms and Swedish fish-do not seem to have the same level of sophistication as the food at this photo shoot.

“It’s a complicated issue,” says McDonagh. “You’re not cooking for just your friends anymore when you’re on the Food Network. You’re not even doing a fun party or a great wedding. You’re talking to more people in more places than you can imagine. I guess our food is a throwback.”

“I like retro food,” says Smith. “We don’t have to apologize for our food.”

Any further discussion is postponed because Proffitt has solved the pâté problem. With adjustment of the lights, the crumbled pâté on a wooden spoon now has depth and texture. The computer screen hooked up to the camera shows a dish that looks as good as it tastes. “Serve it up,” says Smith. “That’s our style.”

***

Growing up in Long Island, New York, Dan Smith lived in a two-generation household. His family-which included his father, who was in the Army National Guard; his mother, who worked in the local school systems; and two older brothers-had one floor, and his maternal grandparents had another. “It was a big, loud Italian family that revolved around food,” Smith says. One of his earliest memories is of eating six meals every day: He would start with breakfast with his parents, then go downstairs and have another breakfast with his grandparents, and so on throughout the day. “Sunday dinners started at 1 p.m. and didn’t finish until around 6 p.m.,” he says. “When you were eating lunch, you were talking about what you were going to eat for dinner. And when you were eating dinner, you were talking about what you were going to eat for dessert.” His grandmother and mother did all the cooking, including handmade ravioli, and they didn’t use measuring utensils or recipes for anything they cooked.

Smith majored in theatre at Marymount Manhattan College, in New York City. “My father always stressed education,” he says. “One of my brothers is a priest with a Ph.D, and the other one is a doctor. So my father used to always say to me, Can’t you add a second major? But now, with a TV show, this degree is finally paying off.” After graduation, while trying to make it as an actor, he supported himself by doing the cater-waiter routine, rather than working in a restaurant, and from that, his interest in food grew. When he was 28, he started fooling around in the kitchen. The first time he ever made meatballs, they tasted just like his mother’s. “It was in the genes, I guess,” he says. He then apprenticed with Francine Maroukian, a small New York caterer who gave parties for Fifth Avenue residents and editors at Town & Country magazine.

McDonagh grew up in Wayne, New Jersey. His parents-British immigrants who moved to the United States in the early 1960s-divorced when he was young. Dinners consisted of basic working-mom fare: meat, potatoes, vegetables. “Always three items on the plate,” says McDonagh. As a teenager, he started cooking for the family-he has one sister. “I was never afraid to be in the kitchen. If you can follow directions, you can cook. But you have to be able to follow the directions of a recipe. It’s when people with no food sense start winging it that disasters occur.” After attending William Paterson College in his hometown, McDonagh left to study acting in Manhattan. He, too, supported himself there as a cater-waiter.

In 1986, Smith and McDonagh met at an audition for a road show of The Fantasticks. They both got cast [Smith as El Gallo and McDonagh as Matt] and started dating. When the show ended, they went their separate ways. Five years later, they ran into each other on the sidewalk outside McDonagh’s New York apartment. Both were in other relationships, and both were headed in different geographic directions: McDonagh was moving to Florida for acting gigs, and Smith was heading to Maine to open a café and a small catering business. They decided to keep in touch and so a letter-writing relationship began.

“I had always thought that maybe he was the one I shouldn’t have walked away from,” says Smith. In 1993, McDonagh and his partner at the time moved to Chicago so McDonagh could pursue stage work. A few years later, the relationships of both Smith and McDonagh ended, and Smith flew out for a heart-to-heart. For a year, they had a long-distance romantic relationship. “I had a business in Maine I couldn’t just walk away from,” says Smith. “But also we both really wanted to be sure that this relationship was what we wanted.” In 1998, Smith moved to Chicago, and the Hearty Boys-a name that plays on both the boys’ book series The Hardy Boys and the idea of abundant food-was born.

At first it was a catering operation they ran out of the kitchen of their Lake View apartment, drumming up business by hanging signs on bulletin boards in their neighborhood Jewel and at the local gym. They concentrated on the gay community because that’s what they felt they knew. “If you are a gay couple entertaining in your home, you don’t want staff or caterers coming in and being judgmental,” says McDonagh. “So we tried to bring a comfort level to our community. And it turned out we hit a niche market.”

Quickly, they established their own style of entertaining. They wouldn’t do fancy-schmancy swagging of tables; instead they encouraged their clientele to go with straight-lined linens on the tables. They considered silver platters too outré; instead they collected serving trays, some colorful, others vintage. And they banned tuxedoed waiters. “Having been cater-waiters ourselves, we knew all about those tuxedos,” says McDonagh. “Waiters don’t have the money to get them cleaned, and they carry them around stuffed in their backpacks. Take a close look and you might lose your appetite.” Instead they told their staff to wear their own black clothes.

“We’re a gay couple, and you should really think about that, because the gays right now, they’re hot.”

From the beginning, it didn’t hurt that the Hearty Boys’ waiters were handsome and hunky. (Their business’s slogan is “Good stuff, not stiff, cute staff.”) And Smith and McDonagh displayed a sense of humor in their marketing: for the annual Gay Pride Parade, the Hearty Boys’ float featured characters dressed like Donna Reed homemakers. Retro with a twist was their stock-in-trade-macaroni and cheese on a stick, beef Wellington, ice sculptures-and they carried the retro feel onto their Web site with kitschy graphics from the forties and fifties. They catered some gay and lesbian weddings, and then heterosexual couples wanted their weddings done by the Hearty Boys, too. “We couldn’t have asked for better caterers,” say Rhonda and Ed Bartosik, who, after taking a cooking class from Smith, asked the Hearty Boys to cater their June 2006 wedding reception at the Newberry Library. “They listened to us and translated what we wanted into a wonderful reception.” For the past five years, their wedding business has risen by 30 percent annually. “We haven’t had any awful brides,” says McDonagh, “because if you want a certain kind of reception you aren’t coming to us in the first place.”

In 2000, the Hearty Boys opened a takeout gourmet food store on Halsted Street featuring whatever they had concocted in their kitchen that day. “I used to stop in every night,” says Michael Conklin, a service representative at Knoll, a show room in the Merchandise Mart. “They do creative but not over-the-top food. It’s like what you grew up with, only much better.” After a couple of years, the takeout place turned into a panini café, and then, in 2004, the space was transformed again-this time into a more elegant dinner spot called HB.

Things were going their way when, in November 2004, McDonagh and Smith decided to enter a contest to name The Next Food Network Star. It was a larky, last-minute decision. Contestants had to send in a three-minute audition tape of themselves cooking and completing a dish; finalists would spend two weeks in New York competing in auditions, with the winner getting a contract for a six-week show on the cable network. Smith and McDonagh decided to do one of their signature cheese terrines.

On the night before the deadline, they bought a video camera and set it up in their catering kitchen. The lighting was darker than a bat cave, but a viewer can still see what would become their trademark on-air near-frantic energy. The audition tape also shows both of them at times endearingly stumbling over their lines. At one point, McDonagh looks at the camera and says, “We’re a gay couple, and you should really think about that, because the gays right now, they’re hot.” It’s hard to interpret his tone: Is he serious? Or is he riffing on society’s search for the next big thing?

“My first reaction to their audition tape was, They could win this thing,” says Bob Tuschman, a senior vice president of programming and production at the Food Network. “They were funny, and the camera loved them. You just got the feeling that they were being themselves. The only thing we didn’t want to do was praise them so much that they wouldn’t grow.”

Tuschman says that the number of complaints about an openly gay couple being on the Food Network “have been so minor as to be dismissible.” As for Bill Buford’s article in The New Yorker, which called Smith and McDonagh’s style anachronistic, Tuschman is unfazed. “I feel that the Hearty Boys have an incredibly accessible aesthetic. They live in Chicago, they live in the heartland, and they understand the kind of food people want to make and people want to eat.”

Although the Food Network does not reveal the ratings of its shows, Tuschman says that the viewership for Party Line has been “consistent from the beginning. The guys built a base during the competition, and they have kept it.”

Until the 1990s, televised cooking shows were the territory of PBS. That is where Julia Child’s The French Chef aired for years; during the 1980s, the most widely watched cooking show in the United States was The Frugal Gourmet with Jeff Smith, another PBS standard. But in 1993, Reese Schoenfeld, a cofounder of Cable News Network, saw food less as a culinary experience and more as a cultural one. He created the cable television Food Network, at first airing little more than shows like The Essence of Emeril, with the excitable Emeril Lagasse, and Chef du Jour, featuring a different chef every week. By 1997, the appeal was narrow: only 19 million households were watching anything on the Food Network. A change in direction occurred a few years later, with an emphasis on personalities over chefs, and on entertainment and practical tips over gourmet cuisine. Now 90 million households watch shows on the Food Network, and about half the viewers are men.

—

|

Photography: Michael Roberts |

| >>Lobster-stuffed eggs and cupcakes, items to be featured in Talking with Your Moth Full, a cookbook by the Hearty Boys |

|

Once Smith and McDonagh received word that they were finalists in the Next Food Network Star contest, they started practicing for the two-week final auditions.

“We’d have JonCarl Lachman, our executive chef at HB, put together a mystery box of ingredients for us,” says McDonagh. The exercise is standard fare on cooking show competitions: open the box, be surprised at the strange mix of ingredients, create something wonderful using everything in a set amount of time. “For our practices, we got the craziest stuff, like ice-cream cones, beets, and mandarin oranges,” says McDonagh. “Or ground veal, lingonberries, and sweet peas.”

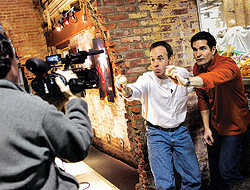

Practice helped, but it didn’t cover every possibility. During the New York audition challenges, Smith and McDonagh, the only couple, had to compete against seven other contestants in Teleprompter readings, mystery basket cooking, and booby traps. “We were supposed to be icing a cake and, unbeknownst to us, the producers had deliberately frozen our frosting, just to see how we’d deal on camera with a disaster,” says McDonagh. “Dan aced it. He just mimed how you’d frost the cake.”

After Smith and McDonagh won the contest, the Food Network offered them a contract for an additional 26 weeks following the promised six. The show would focus on entertaining, and, naturally, Smith and McDonagh already had a retro name in mind: Party Line. They spend a day and a half in New York every other week filming the show, which appears at 8:30 a.m. on Sundays. In each episode, they complete three recipes in just 17 minutes, and McDonagh offers a tip on entertaining culled from his catering experiences.

“We don’t do it for the money,” McDonagh says. “We do make money on the ancillary things-appearances, et cetera-which push everything into the five figures.”

On the Food Network promos, Smith and McDonagh face the camera, sitting on a couch and talking about how they like to entertain. At one point, Smith says, “There are two of us [on this show]. We’re like the American version of Two Fat Ladies,” a reference to a popular British cooking show from the late 1990s.

McDonagh gives the camera a wide-eyed look. “You just called me fat,” he says.

***

Someone is in the kitchen with Smith and McDonagh; it’s Hutton, their Lab-chow mix. Nate, their 15-month-old adopted son, has just gone to bed, and it is time to open a bottle of wine and kick back a bit. In their two-story Rogers Park house, everything is perfectly arranged: beautifully restored furniture from the twenties and thirties; a vintage French poster on the main wall of the dining room, which is painted a pumpkin color; and the kitchen, freshly renovated with stainless-steel Viking appliances, cherry cabinets, pale sea-green glass tile backsplashes, and an island with a pristine butcher-block counter. “I can’t wait to get this marked up with use,” says McDonagh.

These days, though, dinner is most often something that Smith brings home from the restaurant. Life is busy. Last week, they were in Napa Valley, judging the Build a Better Burger contest at the Sutter Home winery. The contest was filmed for the Food Network. It gave Smith and McDonagh face time with James McNair (“You know who he is, right? The king of single-subject cookbooks”) and a nice break from their routine in Chicago. Surprisingly, while there they didn’t try to make reservations at The French Laundry, one of the most prestigious restaurants in the country today.

“Because my memory sucks and why should I pay $250 for one meal I won’t remember?” says McDonagh. “Instead we went to a great French bistro.”

“This is one way we differ,” says Smith. “I feel the need to go out more because it gets my mind working. I’m sure if we had gone to The French Laundry, I would have pulled a lot from that, too.”

“Like the silverware?” McDonagh shoots back.

“We get to reach so many more people than we ever would any other way.”

The Food Network’s move away from culinary school–trained chefs and toward cooks-cum-entertainers is not lost on the two men. Discussing the change, they pepper the conversation with the first names of Food Network stars. “Certainly the Food Network is evolving into something other than what it began as,” says Smith. “Sure, Bobby [Flay] and Mario [Batali] are still there, and they are chefs who have come out of the traditional mold: go to cooking school, work your way up through kitchen after kitchen. But more and more now, what the Food Network is interested in is people who didn’t come up the traditional way. Giada [De Laurentiis] didn’t work in kitchen after kitchen. Rachael [Ray] didn’t, either.” De Laurentiis is the host of Everyday Italian; Ray, of 30 Minute Meals.

“We know all these people now,” says McDonagh. “My knife skills are not as good as a chef who works in our restaurant. They just aren’t, even though I practice. But then the other day Rachael was saying that she doesn’t cut an onion ‘the right way.’ But she knows how to reach people. And that’s what we do as well. I’m always very careful in comparing myself with the chefs because they have different skills, and we can do things they cannot.”

—

“I’m a chef,” says Smith.

“But cutting an onion the way you’re taught in culinary school is hardly that important in real life. Even in TV life. Who’s to say what’s right and what’s wrong? In the end, either way you end up with chopped onion.”

Did either of them ever watch any of Julia Child’s shows?

“Not really,” says Smith. “As a kid, I remember seeing some of The Galloping Gourmet.”

What do they think of Martha Stewart?

“I’d be a little intimidated to be cooking with Martha on her show, wouldn’t you?” asks McDonagh.

“She’s driven, but that’s not a bad thing,” says Smith. “I think it would be fun.”

Ina Garten, the Hamptons-based Barefoot Contessa?

“She’s endearing,” says Smith. “She has a connection with the camera.”

Paula Deen, the queen of Savannah cooking?

“We love her,” says McDonagh.

|

“When we met her, she said, ‘Hug me like y’all mean it,'” says Smith. “And she’s inspirational. She didn’t start cooking professionally until she was 42.”

Early in 2007, Smith and McDonagh should have the word on whether their show Party Line on the Food Network will be renewed. “I think we have a good chance,” says Smith.

“And, worst case scenario,” says McDonagh, “there is Bravo and TLC. But don’t get me wrong. I love the Food Network.”

Still, the two admit that they have had to change things a bit for television, partly because of potential advertising conflicts. “First of all, you can never say anything that’s a brand name, no matter how integrated into the language it is,” says McDonagh. “Like ‘Ziploc bag’-you can’t say that. That’s a brand name.”

And they have had to change ingredients sometimes, like eliminating rose water from a recipe because, can people in the Ozarks get that? “You have to focus on food for everyone,” says McDonagh. “And for our Mediterranean show, we couldn’t use Israeli couscous-you know, the big kind?-because that’s not available everywhere, either. Some people call this ‘dumbing down’ the food, but I don’t think so. We have to be able to connect with people all over the country now. Dan, do you call that ‘dumbing down’?”

“We get to do things we like, we get to reach so many more people than we ever would any other way, and we get paid for it,” says Smith. “I call that lucky.”