For more than five years in the early 1990s, Sudhir Venkatesh, a graduate student in the University of Chicago’s Department of Sociology, practically took up residence in the Robert Taylor Homes, widely viewed as the poorest and most dangerous public housing in the country. He was there to gather data for a dissertation on the underground economy operating in the shadow of the Chicago Housing Authority. (His findings on the economics of drug dealing became the basis for the chapter “Why Do Drug Dealers Still Live with Their Moms?” in Freakonomics, by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner.)

For more than five years in the early 1990s, Sudhir Venkatesh, a graduate student in the University of Chicago’s Department of Sociology, practically took up residence in the Robert Taylor Homes, widely viewed as the poorest and most dangerous public housing in the country. He was there to gather data for a dissertation on the underground economy operating in the shadow of the Chicago Housing Authority. (His findings on the economics of drug dealing became the basis for the chapter “Why Do Drug Dealers Still Live with Their Moms?” in Freakonomics, by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner.)

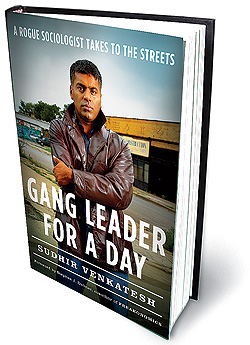

In the process of his research, Venkatesh forged a remarkable friendship with a man he calls J.T., a charismatic, college-educated leader of the Black Kings, a crack-dealing gang that ran the 16-story high-rise that was the focal point of Venkatesh’s work. A product of the Robert Taylor Homes—his mother still lived there—J.T. provided Venkatesh with unprecedented access to gang life in the projects, as well as entrée into the lives of hundreds of tenant families and “off-the-books” squatters. Venkatesh—now a professor of sociology and journalism at Columbia University in New York—presents a highly personal account of his experience in his new book, Gang Leader for a Day (being published in January by Penguin Press).

Raised in the predominantly white, privileged suburbs around universities in Syracuse and Irvine—his father is a business school professor—Venkatesh, now 41, had had little contact with African Americans or poverty before moving to Chicago. By his own account a geek in college, in graduate school at the U. of C. he came under the tutelage of the sociologist William Julius Wilson (now at Harvard), who helped educate him about race and poverty.

The start of Venkatesh’s fieldwork was predictably rocky. In the first building he tried to canvass, J.T.’s soldiers waylaid him at knifepoint and held him prisoner for nearly 24 hours, thinking he was a spy for a rival gang. Before ordering his men to release the shaken researcher, J.T. offered a bit of advice: In the projects, you’ve got to get to know folks before asking a lot of personal questions. Venkatesh returned to J.T.’s building that same afternoon, and he kept going back until J.T., impressed by his gumption, brought him into the heart of his veiled, complex world. Along the way, Venkatesh witnessed crack deals, drug abuse, assaults, and drive-by shootings—as well as acts of extraordinary generosity and sacrifice.

He discussed his experience at an apartment not far from his office at Columbia. This transcript has been edited, and, as in the book, the names of people and of the gang have been changed.

Photograph: Peter Ross

Q: When you first began researching in the projects in September 1989, did you have any idea you’d still be there six years later?

Q: When you first began researching in the projects in September 1989, did you have any idea you’d still be there six years later?

A: No. I had a survey in my hand. I thought if I could talk to 50 kids growing up in different neighborhoods, I could get an understanding of young people’s lives and go back to my office after a week or two and go get myself a job.

Q: At what point did the scope of your research change?

A: When I met the parents of these young men in the gang. To this day I’m trying to grasp how they were able to keep their families together while trying to deal with these issues of poverty, crime, people bringing drug money into their home. And I didn’t see that my sociology training offered any tools at the time. By that, I mean I was being taught that these were isolated families, families outside American society, and it just didn’t look like that to me. These parents were doing all the things my parents were doing, all the things that most parents are doing.

Q: What kinds of things are you talking about?

A: When I met J.T.’s mother, Mrs. Mae, I didn’t see a mother who was dealing with a gang leader. I saw a mother who was dealing with a son who had a college degree and who wanted him to be a better person. For example, there was a time when J.T. had beaten up his cousin. [J.T. explained to his mother] that his cousin had stolen drugs, and she sat there and on his terms tried to find a more appropriate way for him of dealing with this. So she said, “Is he a good worker?” And he said, “Yeah, he’s a very good worker.” “So would you say he made a mistake?” “Yeah, he made a mistake.” “Well, you don’t want to lose your good workers when they make a mistake, ’cause the world’s not filled with very good workers.”

So I sat there listening, and I was just perplexed that she was dealing with these issues the way any mother might deal with her children’s problems at school or work. I’d been taught this idea, which is what sociologists have, that there’s this kind of predator-prey model of a law-abiding element and a criminal element, and they’re battling it out in the streets. Well, here we were in one home, and I realized it’s a much more complicated process.

Q: Why do you think J.T. was willing to take you into his confidence?

A: I think he was looking for legitimacy from a world that he thought had shunned him, and I was coming from that world that he had just left. [J.T. had worked downtown in a sales job but quit to join the Black Kings because he felt his background was blocking his chances for promotion.] He felt very bitter toward that world. He looked at me as someone who would publicize his opinion, give him a voice.

That changed in two ways. First, I think explaining to me how complicated his decision making was made him feel as though he were more skilled and more adept than even he thought he was. And he was already very egotistical.

The second thing occurred five or six years into my research, around the time the feds began investigating the Black Kings. He came to believe he was going to die or go to jail for the rest of his life. I think it was at that point he became a little more interested in my telling his story than in my being just his spokesperson.

Q: How did you feel about what J.T. did for a living?

A: When I started I thought what J.T. did was heinous. But then my affection for J.T. made me overlook his flaws. Also, I knew if I alienated J.T., I couldn’t walk back into the projects. My entire project depended on his goodwill. I was caught up in going deeper and deeper.

The way I justified it was access—a small price to pay. But then I realized J.T. was part of a larger structure, the [political] machine and the citywide gangs, that was raping Chicago’s public housing. He was playing along to get along. He kept saying the gang was going to help the community, but I just didn’t see it. I found that mythic and irresponsible.

Q: What did you learn about the gang members that surprised you most?

A: First, what they were scared of. These were people who were ready to use violence at a moment’s notice but were terrified of being called on by their teachers at school. And, second, how much they wanted to get out of that [gang] life but were scared to admit it to their friends.

Q: Why do you think they wanted to get out so badly?

A: I think partly it was the corporate nature of the work. I was struck by how routinized and predictable daily life in a street gang turned out to be. But mainly it was the money. Probably the first stereotype I had to question was whether being in a gang was monetarily rewarding. I discovered that three-fourths of the gang members were holding money that belonged to others higher up. The idea of big earnings—or even a decent wage—was a grand illusion that rested on the fact that only the higher-ups were making real money.

Q: So why did so many young people join the gangs?

A: Other than status and a sense of belonging, being in a gang meant you were working—and working in the context of a community where 90 percent of folks weren’t working. Membership in the gang gave not only status but a sense of purpose and self-esteem. I must have witnessed countless scenes where kids would suddenly pick up and say to their mothers, “I gotta go on my shift.” It was like watching one of those 1950s TV shows when the man of the house leaves for work.

Q: According to your book, nearly everyone in the projects was implicated in some kind of illegal activity. Did that affect the way you thought about the gangs?

A: After about three or four years in the projects, I began thinking of these folks as victimized and not as criminals, which was equally inaccurate in some ways. I defended them at all costs and took a very romantic view, writing of their crimes as the actions of people who had no other choice.

Then Mrs. Mae and other community leaders asked me to meet with some reporters from the Tribune. I’d marshaled these statistics about poverty and the neglect of the Housing Authority, and I immediately started defending the street gangs, and Mrs. Mae and the other leaders were shocked. They took me aside and they said: “Don’t ever pity us again ’cause we’re not here to be pitied. You don’t have to make excuses for our sons. We’re not asking them to go kill people.”

So I had to figure out a way to not victimize them, and I decided a better way to write about these folks is to pay attention to their aspirations, their dreams. This may sound trite or silly, but sociology has no place for dreams. Sociology tells us we get pushed around by social forces that are outside our control; we’re largely not thinking, dreaming, feeling human beings. And so I spent the better part of 18 months getting people to explain to me where they wanted to go in life and what they hoped to achieve.

The first time I got a glimpse of who these folks really were was when these street gang leaders told me they wanted to mow their lawns on Saturday mornings. They’re sitting in this project, but what they really want to do is put fertilizer over this suburban lawn. They had this vision of Americana. It sounded like they wanted a sense of ownership—not even ownership in the sense of a house, but ownership over their own life and how it was going to grow, [the feeling] that they could in some sense determine their fate.

After a year or two under J.T.’s aegis, Venkatesh began cultivating other sources, most notably Mrs. Bailey, the formidable tenant leader who ran her building with the same ruthless efficiency that J.T. employed on the street. Gang Leader portrays her as both a pragmatic, hands-on executive who bent the law to protect her constituents and a bully who exploited her leverage with the CHA and the police to extort bribes from tenants needing building services and get kickbacks and rent from the squatters and prostitutes.

Q: You seemed conflicted about Mrs. Bailey and her role in the community. How do you feel about her in hindsight?

A: She was a very, very good Chicago politician. If that means I’m still unable to adequately resolve her selfishness vis-à-vis acting only on behalf of the constituents in her tribe—well, so be it. I want to either love or hate her, but I can’t, for the same reason I can’t either love or hate this city.

Q: In your book you describe Mrs. Bailey charging tenants for CHA services that are supposed to be free. How can that be the system’s fault?

A: Because public housing was neglected by everybody. Bailey, and J.T., too, were filling a void, and there’s no reason to expect that it would have been filled if they weren’t there, because no one gave a damn. If Mrs. Bailey had become more selfish, she would not have been a leader. But if she had become more philanthropic, she would have been kicked out of the very structure that was giving her resources. So she got along to get along. There’s an old Chicago expression: “Don’t make no waves and don’t back no losers.”

Gang Leader goes on to describe a world, reminiscent of some early immigrant communities, in which the gangs provide residents with their first line of security, and an underground economy, regulated and taxed by J.T. and Mrs. Bailey, predominates. Yet amid the discord and venality, Venkatesh depicts the subsistence of a strong, viable community—residents pooling resources, helping one another through family emergencies, and celebrating their lives together with a constant round of barbecues, picnics, and holiday fests.

Q: At times you seem to be describing a paradox. Just when you think the community is collapsing into chaos or gang war, it rises up and reasserts itself. Can you explain how that happens?

A: The best example of that was the drive-by shooting. A few years into my research, there was an incident in which an enemy of the Black Kings gang drove by in a beat-up old car, several shooters in the car, and shot randomly at the building. It was a hot summer day, and there were all these people outside on the lawn in front of the building, and one of the officers of the Black Kings gang named Price got hit. So I and a couple of other people actually ended up taking Price and dragging him inside and then also helping get mothers and children and everyone else inside the building. And it really rattled everybody. It rattled me because I still wasn’t used to knowing what to do in these shootings, which is that you bend your knees and you duck. I just sort of stood there like a tree.

In the aftermath a number of things occurred. First, the residents did not make a 911 call to the police. Price was a gang leader. They had to find a way to take him to the hospital without involving the police. [A tenant drove him and he later recovered.] But I think there were a couple of other older women in the building who were traumatized, and they had to get them help. They were having panic attacks. So they called these empathetic police officers to call the ambulance to come and meet them.

Then the street gang and the community leaders got everyone inside and made sure that everyone had what they needed for the next 24 hours, because there was fear that the shooters were coming again. So they went to the store, got water and food for everyone in the building, and, mind you, all of this is occurring without the police.

[After 24 hours] they call the police and try to get them to have officers on patrol, so that the kids can get to school. And then they set up a meeting behind closed doors with the three gangs that are fighting and the tenant leaders, some of the empathetic police officers, and a pastor that has the respect of those three gangs—and they figure out why the gangs are fighting each other and what it’s going to take to stop this war.

That made me wonder: OK, what is this place? Well, certainly it’s gang infested, but that only tells us 25 percent of who these people are and what it’s like to live there. [The residents are also] resilient, courageous, in some sense democratic. They’re creating a place where they can debate each other and figure out how to protect their home community.

Q: But what difference does it make if they can’t prevent these kinds of public shootings in the first place?

A: Most social scientists who look at this community just look at the fact that the crime occurred and say there’s nothing we could do. We need to tear the community down. We need to get rid of the gangs and so forth. But what we could also do is find the people who in the days and weeks after the drive-by kept life relatively stable and use them as community leaders, as places to give money and to invest resources and to build programs.

But that’s exactly what the Housing Authority did not do when they tore down J.T.’s building a few years later. I’ve been following 400 families who were relocated from the South Side projects. Ninety percent of them have been moved into equally poor segregated housing—but now they’re isolated from former neighbors and helping networks—in the southern reaches of the city, where there’s not even a hope of churches and settlement houses replacing the services they lost.

As Venkatesh extended his stay in the projects, he became increasingly involved in the lives of his subjects. Against Mrs. Bailey’s advice, he helped a crack-addled single mother. J.T. made him gang leader for a day, and Venkatesh participated in a kangaroo court judgment that resulted in a gang worker’s beating. The researcher clearly crossed the line between sociologist and subject in the wake of an assault on a young woman resident, an aspiring model named Teneesha, who was beaten and raped by her self-appointed manager, a squatter known as Bee-Bee.

Q: What happened in the incident with Bee-Bee?

A: I was in the stairwell, and there’d been a report that a woman had been beaten up and the perpetrator was still in the building. I was told by Mrs. Bailey to leave, but I stayed anyway. Meanwhile, she rounded up the squatters in the building as a militia. This was a practice 30 years old, that the squatters and the people living off the lease had to answer to Mrs. Bailey and protect the women in the community.

Again, they didn’t call the police first, but they had to get this guy out of the building, and they found out he was on a top floor running down. There were 16 stories. I was in back of these squatters and they were in the stairwell and you could hear slowly the rumbling of somebody coming down. It was terrifying ’cause I wasn’t sure what they were actually going to do to this guy. And I didn’t know whether he was armed, whether he had a knife or a gun, and they were worried about the same thing, too.

So he runs out and they try to tackle him because he’s a big guy. He’s a young guy and he has a football player kind of build. Very menacing. And he looks like he’s high. So I’m very nervous. These folks look nervous, too, but they immediately try to pounce on him, and he gets one of them in a kind of chokehold, preventing him from breathing. Instinctively—I never actually did this before—I think I kicked him and I managed to help wrestle the chokehold off. And they get this guy, and they take him into a room where Mrs. Bailey comes, and they ask me to wait outside. And then you could hear the beating. It was very eerie to listen to the sound of fist on bone, the kind of muted grunts over time when someone is losing their capacity to feel pain.

Q: Did it occur to you to try to intervene?

A: I was dizzy and I was seated on the floor. I couldn’t really. I was having trouble breathing. I was really kind of shook up by this whole thing.

Q: More than any other event you describe in Gang Leader, the Bee-Bee incident signaled to me that you had become a participant in your own research. How did you feel about it at the time?

A: The 24 hours after this I had several thoughts. The first was that J.T. and Mrs. Bailey were going to kick my ass basically for not leaving the building. Because they had been doing everything they could to try and protect me and make sure that I wouldn’t become involved in this way, and I felt this was the time where I would not be able to come back in the building again.

The second was, I really started to worry that I was an accessory. It was one thing watching a drug dealer’s exchange. In some ways you’re not going to be able to avoid that. Another thing is actually kicking somebody and getting involved in physical combat. I thought I had crossed the line in some way.

Q: What happened?

A: For about 48 to 72 hours I remember thinking, You know what? At the end of the day you went after a guy that had been abusing these women. And I started realizing at that moment—that’s when the shivers and the chills came over me—that I was actually going through the same rationalization process as the people that I was studying, that I was embracing what was good and what was bad about their lives.

Q: How did that make you feel?

A: I think I’d had a real problem feeling human. And that’s what it made me feel. They—J.T., Mrs. Bailey, other residents that I got to know—would consistently tell me that I’m no better and no worse than them, that I was hustling just like they were, using them to get ahead. And I think they were right: I couldn’t hide behind my academic guard any longer.

As he withdrew into the world of his research, Venkatesh also became alienated from many of his professors and colleagues, who took a dim view of his participatory brand of sociology as subjective and narrow. Sometimes called urban ethnography, Venkatesh’s approach had been pioneered at the University of Chicago but had fallen into disfavor by the 1960s, when mainstream sociologists embraced the breadth and rigor of large-scale surveys and quantitative analysis.

Venkatesh’s adviser, William Julius Wilson, did try to encourage his efforts, but when Venkatesh outlined his actions in the stairwell, even Wilson told him to take a time-out.

Q: Why did Wilson tell you to stop?

A: I think he felt I was getting too close to the material. I was becoming angry, depressed—keeping everything in.

I felt I wasn’t doing academic work, that it wouldn’t be viewed as scientifically rigorous or even as sociology.

Q: Do you think you could have accomplished as much without getting as involved as you did?

A: The only way to begin learning about another world is to understand that you have an emotional stake in it. That’s where it has to start. I think that’s what I discovered after doing this research.

Q: Do you think your approach led you to understand the world of the projects?

A: Where most sociologists were looking at causes of crime, I was blessed to look at reactions to crime. We were all trying to prevent the ill effects of poverty and dysfunctional public housing. But I was able to see how folks actually responded to those conditions, how the community functioned—and that here was a community.

Social science defines the poor by what they don’t possess—no jobs, no fathers at home, no safe streets. And what I saw, what I looked at, was what was in place, not what was missing, and we can learn from that.

* * *

After her building was demolished, Mrs. Bailey moved to another low-income neighborhood, but she lived out her remaining days without ever regaining the power she had held at the Robert Taylor Homes. J.T. retired from the drug-selling business a few years after Venkatesh ended his research in the projects. J.T. currently manages several small businesses owned by relatives and lives off the money he saved while working and consulting for the Black Kings.

Venkatesh says that the citywide gangs operating during the era of his research have largely fragmented into smaller groups whose members tend to age out after high school. The demand for drugs, especially crack, has declined, and the population of users once concentrated in the high-rise projects is now dispersed throughout the city.

Today, while continuing to examine the Chicago Housing Authority, Venkatesh is researching a book on the veiled worlds of Arab immigrant communities in France and cocaine dealers and privileged youths in New York.