Nnedi Okorafor goes to the gym to rest. Not to bulk up or slim down, not to seek strength or flexibility. Okorafor, an award-winning science fiction writer, works out daily to halt her propulsive mind. And what a mind it is — her brain has brought forth 18 works of fiction, including novels for children and adults, a short memoir, and five comics. Soon her storytelling will shift to the screen: HBO is developing her postapocalyptic novel Who Fears Death into a drama series, with Game of Thrones creator George R.R. Martin as executive producer. Hulu is adapting Okorafor’s outer-space coming-of-age novella Binti.

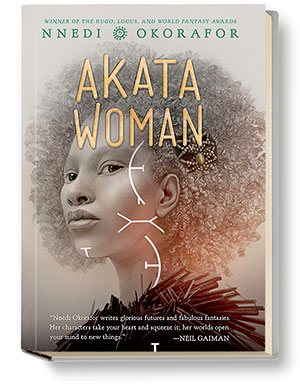

Her newest work, Akata Woman, the third book in the Nsibidi Scripts series, hits shelves this month. The YA series follows a 12-year-old Nigerian American girl who discovers she has magical powers and embarks on high-stakes missions with her friends. It comes just two months after the release of the popular writer’s latest adult title, Noor, about a woman in Nigeria in the near future whose body is extensively augmented with biotechnology.

Nigeria is the setting for most of Okorafor’s novels. (She defines her work as Africanfuturism, not to be confused with Afrofuturism. The former is science fiction that’s rooted in Africa; the latter centers on African Americans.) The U.S.-born child of Nigerian immigrants who never lost sight of their heritage, Okorafor was raised in suburban South Holland and Olympia Fields, but her family visited Nigeria annually.

While West Africa has always occupied her heart and imagination, writing came later. At age 20, Okorafor underwent surgery to correct severe scoliosis. The procedure left her temporarily paralyzed from the waist down. In the hospital, she picked up a pen and wrote a story. She never stopped.

I spoke with Okorafor, 47, over the phone about her writing process, her hopes for the future of science fiction, the book that transformed her, and, yes, the gym.

What is your process like? Your output is amazing.

I love writing. I’ve loved it since I discovered it in the hospital. I enjoy it. It’s not suffering to me. It’s a release, it’s a joy. It is work, but it’s good work, and very, very fulfilling. I’ve written so much that a lot of things are intuitive now, like writing a novel. I don’t need to think about structure because it will take care of itself. I don’t outline, I don’t plot. I just write when it comes. My process is really chaotic. It’s organized chaos. Lately, I’ve been meditating in the morning. I use apps like Headspace and Calm. Then maybe I’ll work on a chapter or a scene. And then I’ll go on social media and mess around, cause some trouble. I go on there to decompress when I feel too much pressure. After, I’ll finish that scene.

I don’t need deadlines because I am harder on myself than any deadline can be. I want to see the finished work. If I look back on all the deadlines for my novels, I hit them all early, probably a month before. I murder deadlines. They have no chance against me because I have that internal pressure. I really want to know what happens to the characters, and I don’t know until I’ve written it. I also like finishing things. It’s very addictive.

When do you rest?

Rest? What’s that? That’s why I go to the gym. [Laughs.] Rest is the gym. It really is. I watch movies there. I listen to music. I love the atmosphere. A lot of people go to the gym for cosmetic purposes. For me, it’s mental. I do need to learn how to rest better. I do.

Which of your books was the most difficult to write?

Who Fears Death. I hope nobody expects me to write something like that again. I was in a very dark place. The book was inspired by the passing of my father, which was extremely traumatic. My father was a cardiovascular surgeon — top of his class, top athlete, just like my mom. My dad was a chief of surgery on the South Side of Chicago [St. Bernard Hospital]. Then he got Parkinson’s disease and debilitating diabetes. Parkinson’s makes your hands shake — a heart surgeon with shaking hands, are you kidding? He eventually passed from congestive heart failure, after spending his life repairing other people’s hearts. I was very, very angry. The night of his wake, I wrote the beginning of Who Fears Death. The first scene is basically autobiographical — before the mystical aspect comes in.

In your 2017 TED talk, you said, “Science fiction is one of the greatest and most effective forms of political writing. It’s all about the question ‘What if?’ ” What’s the “What if?” you want readers to consider when engaging with your work?

What if Black women were truly powerful? I’ve read a lot of African literature, especially when I was in graduate school at Michigan State. I found the African literature section at the library and read everything on the shelf. I came away feeling like I wanted to see Black African women be powerful, I wanted to see them win. In so many of those books, they did not win. I was reading realism. I thought, What if they won? And what if they were so powerful that sometimes they destroyed shit? What if they used their valid anger, and what if it wasn’t in the most acceptable way? I wanted to see that. I wanted to dismantle the patriarchy. But my writing is not just about race and gender. I love creatures. I love immersive worlds. I love dwelling in those worlds. The women’s stories are big, but the worlds are big as well.

Your novels are about the future. What do you hope the future of science fiction as a genre looks like?

It’s cheesy, but I hope that diversity becomes the norm so we don’t have to even say “diversity” anymore. I don’t want to be called a “diverse writer.” Just call me a writer. I don’t hope that there will be no white men writers or no stories about white men. I want stories by them, but I want stories by other people, too. I want it to be easy to find whatever type of story you want to read.

What are some of your favorite books?

Wizard of the Crow [by Ngugi wa Thiong’o], The Talisman by Stephen King [and Peter Straub], Life of Pi [by Yann Martel], and Ben Okri’s The Famished Road, which is like a dream, so psychedelic. It’s probably the most influential book for me. It’s about a young boy who was born with spirit friends, but it’s an adult novel. He views the world in such a way that the mystical and mundane coexist. It’s set in Nigeria during a very politically tumultuous time. Akata Woman, my new book, pays homage to The Famished Road. The first time I read it, I was an undergrad. This guy I was dating had gotten it for an African studies class and I just stole it from him. He didn’t care. He didn’t even read it. For me, it changed everything.

In 2011, you became the first Black person to win the World Fantasy Award. The trophy was modeled after the famous 20th-century horror and fantasy writer H.P. Lovecraft. You later learned about the extent of his racism and wrote a blog post that ultimately led to the trophy’s design being changed. But you’ve also said that you don’t simply want to erase ugly history. What are your thoughts on cancel culture?

My thoughts are complex. I’m all about dialogue. With the Lovecraft statuette, I wasn’t demanding that they change it. If I just made that demand — especially back then — that’s all the story would become. I wanted there to be conversation about the fact that this racist, antisemitic writer was upheld, and upheld by a lot of my favorite writers. They weren’t talking about his racism; they weren’t dealing with it. None of this is going to get any better if we don’t face the issues, the ugliness. Facing it is not fun. It’s painful, it scars. But in the long run, it heals. I’m not about erasing or replacing. I understand cancel culture. I know that there are things that it has solved. But it’s not perfect. We have to have painful conversations, and those conversations involve hearing terrible things. That’s part of the process, unfortunately. There’s going to be more pain before the healing comes.