Editor's note: Since this story went to press, two new witnesses came forward to further implicate Michael Gargiulo in the murder of Tricia Pacaccio, and on July 6th, Chicago learned that Cook County authorities would charge him with killing the Glenview teen. Read the latest update in the following 312 blog posts: "Michael Gargiulo to Be Charged with Killing Tricia Pacaccio" and "Pacaccio Parents Blast Cook County State's Attorney's Office." PLUS: More details, including an exclusive interview with Temer Leary, one of the witnesses, here.

The mother and father mount the stairs in silence. They trudge to the second floor of their modest two-story house in Glenview and stand before the bedroom just to the left. They have visited this room many times over the years, but each time they pause for a moment at the door, like mourners collecting themselves before entering a funeral parlor. The father’s eyes are fretful, searching. The mother turns the knob with a trembling hand.

The room is heartbreaking. All pastel pinks and powder blues. Porcelain clowns line a set of shelves. The words “Happy Sweet 16” shimmer on a piece of poster board, the letters made of glitter glue.

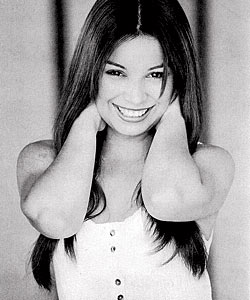

“Everything is just the same,” the mother says. She pauses, spots a framed photo of her daughter. The girl’s dark hair, parted on the left, falls gently over her shoulders. Her smile is girlish, sweet, tinged with yearning. “She’s got a beautiful face, this girl,” the mother murmurs. “A beautiful, beautiful face.”

The father lets out a sudden sharp sob. He turns and waves at the air, as if beating back an attacker. He staggers toward the door. “I gotta go,” he says.

Eighteen. That’s how old she was when it happened—and the number of years that have passed since that night, August 14, 1993, when, between 1 and 2 a.m., someone approached the petite girl with the beautiful face, twisted her left arm so hard it snapped, then plunged a knife into her half a dozen times on the stoop of the side door to her home. By the time the killer was finished, Tricia Pacaccio had been stabbed in the heart, the lung, the abdomen, the arm, the collarbone, and the back. Rick Pacaccio, her father, found her slashed, blood-spattered body the next morning. He was coming out to walk the dog. “Actually, what I first saw were her two little tennis shoes sticking up,” he says, his voice catching. He fell to his knees that day and screamed. His cries echoed through the cul-de-sac. Diane Pacaccio, the mother, blacked out. Both parents were taken to a hospital in shock.

On a stormy Sunday this past March, they sit at their kitchen table and tell you the story with haunted eyes, their anguish punctuated by the occasional nerve-rattling stab of thunder. You listen to the tragic, incredible, baffling tale—of her death and their desperate search for justice—realizing you’re sitting just a few feet from where it happened. And you begin to understand why their pain is still so fresh, why for them the moment is frozen in time, like the room upstairs that they refuse to alter, the shrine to their suffering.

Eighteen years. And they’ve wanted but one thing: Catch the guy. Charge him. Let a jury, the world, decide whether he’s guilty. Their best hope: foreign DNA found on their daughter’s fingernails. For years they waited: through the first frustrating leads that faded, the trail that went cold. They waited through the string of detectives who came and went, who were reassigned or transferred or who resigned.

Then, in 2006, a Hollywood homicide detective called. He was in Chicago investigating the similarities between Tricia’s death and the 2001 stabbing murder of a Los Angeles woman named Ashley Ellerin, who was linked romantically with, among other celebrities, Ashton Kutcher. During the conversation, the detective, Tom Small, dropped a bombshell: Were the Pacaccios aware that in 2003 the DNA of a suspect in Ellerin’s murder—a man named Michael Gargiulo—had been matched to DNA found on Tricia’s fingernails?

The parents were not. They had no idea. No one had told them. They were furious—and elated. Before he moved to L.A. in the late 1990s, Gargiulo (pronounced gar-ZHOO-loh) had known the Pacaccio family. A friend of Tricia’s younger brother, Doug, he had even been in the house a few times. Although Gargiulo and Tricia attended Glenbrook South High School at the same time, the two were never friends and could barely be called acquaintances. One other thing made sense: Gargiulo had a reputation around the neighborhood as a short-fused bully with a violent, volatile temper.

Having met with Small, the Pacaccios demanded answers. After the DNA match, why hadn’t Cook County charged Gargiulo? There wasn’t enough evidence, insisted prosecutors from the office of the Cook County state’s attorney. Because Gargiulo had occasionally been in the Pacaccio house, it’s possible that the DNA could have wound up on Tricia’s fingernails through casual contact, they said. “I was so insulted,” says Diane. “I don’t know how they want to twist and turn it, but they know his DNA shouldn’t have been on her.”

Gargiulo was eventually arrested—in 2008 in Los Angeles. Now 35, he awaits trial in L.A. County jail for the 2001 murder of Ellerin, the December 2005 stabbing death of an El Monte woman named Maria Bruno, and the vicious 2008 attack on a Santa Monica woman named Michelle Murphy. L.A. detectives call him a serial killer and suspect he was involved in as many as ten slayings—including homicides that may have occurred after the 2003 decision by Cook County prosecutors not to charge him. The office of the Los Angeles County district attorney says that it will seek the death penalty. Gargiulo has adamantly denied any involvement in the L.A. killings and the death of Tricia Pacaccio. His lawyer, Charles Lindner, did not return calls for this story.

The Pacaccios have found some solace in the fact that Gargiulo is behind bars. “When the California detectives called and told us Mike had been arrested, I can’t even tell you what a load was lifted,” says Diane. “We just want the same justice for our daughter.”

After nearly two decades of waiting, they may get it. In late May, as the July 2011 issue of Chicago went to press, word surfaced that two new witnesses, responding to a CBS 48 Hours Mystery episode about the case, had come forward claiming that, sometime in the late 1990s, Gargiulo told them that he killed Tricia. Chicago learned that the two witnesses are Temer Leary, 37, of Lake Luzerne, New York, and Anthony Dilorenzo, also 37, of Van Nuys, California. In an exclusive interview with Chicago, Leary confirmed that Gargiulo had told him and Dilorenzo that he killed Tricia Pacaccio. Leary also revealed that Cook County detectives had flown him and Dilorenzo to Chicago and that both of them had told their story to an investigative grand jury here. A source close to the investigation says that the two witnesses are “rock solid.”

And finally, this new evidence prompted Cook County state's attorney Anita Alvarez to charge Gargiulo with Pacaccio's murder. On July 6th, 2011, Chicago learned that authorities would announce the charges the next day.

The news is bittersweet for Tricia’s parents. Although their long wait for justice may finally come to an end, this recent news has not extinguished a question that still smolders—and not only for the Pacaccios. Two Los Angeles detectives, as well as two former Cook County detectives who investigated Tricia’s case in the late 1990s, have openly denounced what they call a lack of will by the Cook County state’s attorney’s office to take action when it really counted. Why, they all wonder, was Gargiulo not charged in 2003 when prosecutors had a DNA match—and when Maria Bruno was still alive and Michelle Murphy had not yet experienced the horror of a man trying to stab her to death? “I can’t put a happy face on this, because we dropped the ball,” says John Reed, one of the Cook County detectives. “No ifs, ands, or buts about it.”

Tom Small, the Hollywood detective, agrees, as he told me over lunch in L.A. last March. “I’m not privy to everything [Cook County prosecutors] have. [But] I gotta say—” He paused, chuckled, rubbed his neck. “If I’d had evidence like that, you’d bet that [the L.A. district attorney’s office] would have had a filing. And these other girls wouldn’t be dead. Plain and simple. They wouldn’t be dead.”

When the investigation began, the detectives did seem to have a few good leads. For starters, the normally peaceful cul-de-sac off Huber Lane teemed with potential witnesses that night in 1993, thanks to a pool party at a neighbor’s house across the street. Police collected physical evidence, including Tricia’s key chain, which they found next to her, and her fingernail clippings. They also found a man’s shoe print.

Then, too, there was the nature of the attack itself. Stabbing murders are rarely random, experts say—the attackers usually have some association with their victims. That meant a ready list of potential witnesses and suspects to interview: Tricia’s friends, her fellow students, her current and ex-boyfriends, people who lived in the neighborhood. Surely someone had seen or heard something.

Because the crime occurred in unincorporated Glenview, Cook County sheriff’s police assumed control of the case. But as weeks stretched into months and months into years, each of those promising leads seemed to evaporate. Detectives interviewed guests who had been at the pool party, only to find that none had seen anything—a thick fog had cloaked the neighborhood in an impenetrable blanket of white that night.

Several of Tricia’s friends, meanwhile, refused to talk, says Mark Baldwin, who worked the case from 1997 to 1999 as a detective with the sheriff’s police. “The parents would say, ‘Listen, the cops are here. You don’t have to talk to them.’ [The detectives] were having doors slammed in their faces.”

As for the physical evidence, the key chain and fingernail clippings were examined, but the testing methods of that time—unsophisticated by today’s standards—yielded nothing of use. The shoe print, it turned out, belonged to Rick Pacaccio. He had left it at the crime scene in the first frantic moments after discovering his daughter.

That left motive. Sexual assault was out. Tricia had been discovered fully clothed with no sign of such injuries. Nothing had been taken from her, so robbery didn’t fit. The brutality of the crime suggested personal animus, but investigators could not find anyone who harbored the slightest ill will toward Tricia.

Pretty and popular, raven-haired Tricia Pacaccio was a parent’s dream and a friend’s good fortune. She was a straight-A student, a math whiz, and a debate team champ—the girl who wrote in her Glenbrook South High School yearbook how much she “liked meeting interesting people who had the same desire as me, to save the world.”

“She was a beautiful person, inside and out—full of energy, full of life, always happy and cheerful,” says Karen Isenberg-Jones, a close friend of Tricia’s and one of the last people to see her alive. “In high school you’ve got cliques, you’ve got girls who are snobby, you’ve got girls who are insecure, and they take it out on other people. She just was not one of those people. She was genuinely nice to everybody.”

The night of her death, Tricia and a group of her friends, including Isenberg-Jones, had gone on a road-rally scavenger hunt as a last hurrah before leaving for college—in Tricia’s case, to study engineering at Purdue University. After a late dinner at T.G.I. Friday’s, the group hung out in the parking lot. Later, according to detectives, Tricia dropped off two friends at their cars, then drove home. Police believe she was murdered sometime after 1 a.m.

For the next four years, the Pacaccio family—Rick, Diane, and Tricia’s two brothers—could not bear to live in the house. They lived instead with Diane’s mother. Rick returned occasionally to water the plants and mow the lawn. “I didn’t want anyone to know we weren’t here,” he says.

The Pacaccios did not, however, give up on their daughter’s case. Diane visited detectives several times a week. She was so persistent that they began to put her off, says Rick. “One time I remember [a detective] calling and saying, ‘You better come get your wife.’ They wouldn’t let her in. They had her sitting outside. You wouldn’t treat a dog like that.” (The office of the Cook County sheriff declined to comment on the case, citing its open status.)

Still, the Pacaccios pushed. And in 1997, Michael Sheehan, then sheriff, assigned a new investigative team, including the detectives John Reed and Mark Baldwin (both retired now). “The case had pretty much been in a dormant status,” recalls Baldwin. “We went out and beat the bushes and relocated the people who had been approached back when the homicide went down. We hoped with the passage of time and the maturity of some of her classmates that they might be more forthcoming with information.”

They were. And within months, Baldwin and Reed had a prime suspect. It wasn’t Michael Gargiulo, however. It was a former classmate of Gargiulo’s at Glenbrook South High School who also knew the Pacaccio family, says Baldwin.

At the time, Baldwin and Reed say, they suspected Gargiulo might have been involved in the crime. Accordingly, they interviewed him several times but did not delve deeply into his background. Had they done so, they might have heard some disturbing stories—namely about what witnesses would later describe as Gargiulo’s dark, explosive temper.

“To watch him in action was something else,” says Scott Olson, who played in a band with Gargiulo. “This guy would go from normal to crazy in, like, a second. If he had something he wanted to do and something got in his way, he would go completely nuts. The switch would flip, and he would just become almost inhuman.”

As it was, detectives discovered several peculiarities. Born in 1976, the lean, athletic, dark-haired Gargiulo lived with his parents and siblings five houses away from the Pacaccios. Like many neighborhood kids, Gargiulo spent time at the Pacaccio house. “The dad was always working on a car, and he would show some of the boys in the neighborhood how to tear an engine apart,” says Baldwin. “Mom was always cooking something. This is a household where it wasn’t unusual in the middle of the afternoon to have two or three of their sons’ friends pop in: ‘Hey, Mrs. P., what are you cooking?’”

Unlike the other visitors, however, Gargiulo never seemed comfortable in the home. Diane told detectives that she would set some food in front of him, “and he’d pick it up and he’d start pacing back and forth like a caged animal,” Baldwin says. “She’d say, ‘Why don’t you sit down with everyone else?’ and he’d say, ‘Well, I can’t.’ And he’d take off out the door.”

Gargiulo’s social awkwardness wasn’t the only oddity that piqued the detectives’ curiosity. Shortly after Tricia’s murder, he began sending gifts to the Pacaccios. “I hardly knew this guy, but he sent me flowers. He bought Rick a shirt,” Diane recalls. “He sent us a coupon for a restaurant. It was weird.”

In the summer of 1997, detectives saw an opening. Gargiulo had been charged with felony vehicular burglary. If he would divulge what he knew about Tricia’s murder, Baldwin and Reed told him, they’d make sure the charge was knocked down to a misdemeanor—with no jail time. “Gargiulo’s lawyer was ecstatic,” says Reed. The detective wrote down a few questions he had and gave them to the attorney. “That’s it,” Reed says. “We weren’t trying to trick him or anything.”

When Gargiulo refused to talk, Reed was dumbfounded. “He turned down what was basically a walk-out for a felony conviction that will stick with him for life,” says Reed. “That’s when the [prosecutor] said, ‘Have you looked at this guy? We should look at him a little more.’”

The Pacaccios, meanwhile, had their own odd encounter with Gargiulo—one that today gives them chills. On a fall day in 1998, Diane says, she heard a knock at the side entrance. When she opened the door, there, standing on the stoop where the murder had occurred, was Gargiulo. “Is Mr. P. home?” she recalls him asking. When Diane said her husband was still at work, Gargiulo asked if he could wait.

“I was shocked,” Diane says. “He had never been in this house for more than five or ten minutes. But he sat down in this chair, in this kitchen, and he waited for over an hour.” When Rick arrived home, he, too, was surprised to see Gargiulo. But he was also hopeful. Did he know something? Were they finally going to get answers? Just as Gargiulo began to speak, however, the young man’s dad and sister burst through the door. “They didn’t knock or anything,” Rick recalls. “They just opened the door, came in, and grabbed him.”

The Pacaccios looked at each other—both shocked and crestfallen. “I said to Diane, ‘Did you see his face? It looked like he wanted to tell me something,’” Rick recalls. “I immediately got on the phone and told Cook County detectives what happened.”

It was the last time the Pacaccios saw Gargiulo, who they were now convinced was involved in their daughter’s death. Almost immediately after that encounter, Gargiulo moved 2,000 miles away, to a new life in Los Angeles.

A few months later, detectives here persuaded Gargiulo to fly back to Chicago and appear before an investigative grand jury. According to Reed, Gargiulo made a stunning claim in an interview before he was scheduled to give his testimony. He said that the day after Tricia’s murder, his friend—the one the detectives were looking at as a suspect—had admitted to killing Tricia. Today, Baldwin remembers the conversation a little differently, but at the time, he and Reed felt certain that Gargiulo’s friend was their man. But, according to a source close to the case, when Gargiulo was brought before the grand jury to repeat the story, he backed off the claim, making it sound like the friend was joking.

Gargiulo’s friend moved out of state and was never charged. Baldwin says that he tracked him down and tried for six hours to persuade him to talk. The friend demanded immunity, which Cook County prosecutors refused to grant. Gargiulo apparently was also done talking—at least to police. After his grand jury testimony, Reed says, he all but fled the building. Not long after, Gargiulo returned to L.A., and Reed and Baldwin became the latest detectives to leave the case.

Though they never knew each other and ran in different circles—in vastly different cities—Tricia Pacaccio and Ashley Ellerin were in many ways very much alike. Both were pretty, sweet, feisty, likable, and fun-loving, and they attracted friends in bunches. Ellerin was the far more worldly and adventurous of the two. Having moved from Northern California to a Hollywood bungalow within walking distance of the Kodak Theatre and the fabled Walk of Fame, she had enrolled in the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising, hoping for a career both creative and glamorous. What’s more, the gorgeous 22-year-old blond had been romantically linked to the actors Vince Vaughn and Vin Diesel. In the winter of 2001, she was dating Ashton Kutcher, then a rising star on the sitcom That ’70s Show.

As different as they were, Tricia and Ellerin shared the same blind spot: The two young women were trusting to a fault, say those who knew them. So it wasn’t surprising that Ellerin welcomed the help of a good-looking dark-haired stranger who appeared in front of her house one day while she and a friend, Christopher Duran, were fixing a flat tire.

The man introduced himself as Mike and gave the two of them his card, saying he was a heating and air-conditioning repairman. Soon he was showing up, often unannounced and uninvited, to parties, trying to ingratiate himself with Ellerin and her friends.

Ellerin didn’t seem to mind. But several in her circle were uncomfortable with Mike’s sudden presence—particularly after a number of disturbing incidents. For example, Ellerin’s former roommate, Justin Peterson, was giving Mike a ride one day when Mike, for no apparent reason, suddenly grabbed his hand and stared at him angrily. Hours later, back at home, he saw Mike sitting in a running car across the street with the lights off. Peterson grew even more uneasy.

The next day, when Mike appeared at the door, saying he needed to come in to look at Ellerin’s furnace, Peterson confronted him. “I looked at him and asked what the heck he was doing in front of my house at three in the morning,” Peterson later testified. Mike “started stuttering” and then said that he couldn’t go home because Chicago investigators “were waiting to collect DNA samples from him [because] his best friend’s girlfriend had been murdered.”

“If you’re innocent . . . why aren’t you over there confirming this?” Peterson said he asked. Mike then pulled up his pant leg and unsheathed a jagged knife from a case strapped to his shin. “I rushed him out of the house and told him I didn’t want anything to do with his business,” Peterson testified.

For Ellerin, the night of February 21, 2001, began full of promise. Kutcher told her he was going to watch the Grammy Awards on television with a friend but asked if she wanted to meet him for drinks afterward. She agreed, and the two spoke twice by phone that evening: once at 7:30 p.m. and again an hour later.

Kutcher later called Ellerin’s cell phone, then swung by her bungalow at around 10:45 p.m. The lights were on, and her maroon BMW was in the parking lot. He knocked on the door, and when she didn’t answer, he tried the handle. Locked. He then peered through the front window, according to later testimony. The place was in disarray, but that was to be expected since Ellerin was in the midst of remodeling. Kutcher also saw a dark red stain that looked like someone had spilled wine near the entrance to her bedroom. Assuming she had brushed him off, he gave up and left.

Half an hour earlier, Ellerin’s new roommate, Jennifer Disisto, had also dropped by the apartment. She had left her keys in her boyfriend’s car and was hoping Ellerin would let her in. Spotting Ellerin’s car in the parking lot and the lights on in the bungalow, she knocked at the door. When there was no answer, she went back to her boyfriend’s house. She returned the next morning around 8:30, having retrieved her keys. A few steps into the bungalow, she came upon a gruesome scene.

Dressed in a turquoise terry cloth robe, silk boxer shorts, and a camisole, Ellerin lay sprawled in a large pool of blood on a carpeted landing leading to the bedrooms, her face already slightly blue. A medical examiner would later testify that she had been stabbed 47 times, including a gaping wound to her neck, so deep that only her spinal cord kept her head from being severed. The rest of her body was covered with deep puncture wounds—to her chest, stomach, and back—some up to six inches deep. One of the blows “actually penetrated the skull and took out a chunk of skull like a puzzle piece,” Tom Small, the Hollywood detective, would later testify. Small noticed something else: The position of the body seemed odd, as if “the victim was moved, possibly posed.” To Small, all the signs pointed to the disturbing possibility that the murderer was a serial killer.

Small began eliminating suspects. Kutcher was quickly ruled out, as was Mark Durbin, the manager of Ellerin’s rental house and a man with whom Ellerin also had carried on a flirty relationship, which had become physical just that night. The two had sex, in fact, sometime between 7 and 8 p.m., despite the fact that Ellerin had a date later with Kutcher. Durbin, who lived nearby with his girlfriend, left Ellerin’s house at about 8:15 p.m. Around 10 p.m., he glanced out his window and saw a figure walking back and forth in front of Ellerin’s.

One person who could not be eliminated was the mysterious “furnace guy.” Through dozens of interviews, numerous leads, and a little bit of luck, Small eventually put a name to the stranger who had inserted himself into Ellerin’s life: Michael Gargiulo. Armed with a driver’s license photo, Small began reinterviewing witnesses. With each person he talked to, he moved Gargiulo another rung higher on his ladder of potential suspects. “It’s one of those things where you get a little itch in the back of your neck, and it kind of bothers you,” says Small. “Who is this guy? What’s his connection? Nobody seemed to know, and yet, as we progressed further into the case, we came to learn that he had been to the house a number of times.”

Small began to build a profile. Six feet two, with a dragon tattoo on his back, Gargiulo was both good-looking and imposing. His arms coiled with muscles, he boxed and worked out at a local gym and also practiced martial arts. He had tried his hand at acting, landing a role in a student movie, but that seemed to be the extent of his film career. In 1999, he took a job as a bouncer at the Rainbow Bar & Grill on the Sunset Strip—a gig he was later fired from after allegedly decking a customer.

Gargiulo also had a tendency to tell tall tales about himself. One was that he was an air-conditioning and heating repairman who had once been electrocuted on a job. Another was that he was a boxer training for the Olympics. “He had an apparent habit of making himself bigger than he was,” Small told me. “He wanted to control people and impress them.” The other, more disturbing tale involved something that had happened in Illinois. According to court documents, Gargiulo told several people either that Chicago police were trying to frame him for a murder he didn’t commit or that they were after him for his DNA.

The more information Small gathered about Gargiulo, the further the detective’s suspicions deepened. But it wasn’t until the fall of 2002—and a visit from two Cook County detectives reinvestigating a 1993 Illinois murder—that Small felt he had hit pay dirt.

The detectives, including Lou Sala from the Cook County sheriff’s cold case division, had taken over for Reed and Baldwin in 2000. One of the first things the new investigators did was submit the physical evidence recovered at the Pacaccio murder scene—including Tricia’s fingernail clippings—for DNA testing at the Illinois State Police crime lab.

The hope was that newer, more sophisticated scientific methods would succeed where the initial examination had failed. And, indeed, the tests did detect DNA from two people on Tricia’s nail clippings: her own and that of an unidentified person. Armed with the information, Sala tracked down and collected DNA samples from more than 20 witnesses in the case—including the friend of Gargiulo’s who initially had been Reed and Baldwin’s prime suspect. None matched.

By the fall of 2002, only one person remained on the list: Gargiulo. Sala and his partner flew to L.A., where they contacted Small in hopes he could help them locate Gargiulo, who had been tough to find since he never seemed to put leases or utilities in his own name. When Small heard whom they were looking for—and why—“bells and whistles went off,” he says.

“The type of attack was similar, the type of victim was similar,” Small adds. “The type of weapon, the manner and method of the attack—the stabbing, the locations—everything is so similar that we all believed it’s gotta be our guy. That’s when we began to work a parallel investigation.”

They tracked Gargiulo to an apartment listed under the name of his latest girlfriend. Search warrant in hand, they found his van, and in it they discovered three knives, binoculars, and a backpack containing a Halloween mask and a handgun. Authorities apprehended Gargiulo when he arrived home and drove him to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center to collect DNA samples. According to sources, a livid Gargiulo fought with detectives and had to be taken to the emergency room. But what really raised eyebrows were comments he volunteered.

“What if my DNA was on a key chain that was left at a crime scene?” he asked, according to later testimony from Michael Pelletier, a Los Angeles police detective who was with Gargiulo during the testing. “They can’t find my DNA from ten years ago at a crime scene, can they?” he also asked, according to Pelletier. “What if my hairs were at a crime scene in Chicago? . . . Can they book me for that?” When Pelletier asked Gargiulo what he was talking about, Gargiulo replied, “Never mind.”

Allowed to remain free pending the outcome of the tests, Gargiulo began a relationship with Maria Gurrola, whom he met while fixing her air conditioner. By February 2003, the two were living together, but things didn’t last. Gargiulo once struck her so hard she wound up with a detached retina, according to testimony. He also allegedly stalked and threatened her, saying he had a degree in forensics and thus knew how he could kill her and get away with it. Gurrola kicked him out and filed a restraining order after a confrontation in a supermarket parking lot.

In September 2003—nearly ten years after Tricia Pacaccio had been killed—the DNA results finally came back. The foreign DNA on Tricia’s fingernails belonged to Michael Gargiulo. Still, Tom Small, lacking any DNA evidence from the Ellerin crime scene, felt he could not charge Gargiulo. His hope was that Cook County prosecutors would help his case—not to mention get Gargiulo off the street—by doing so instead.

At the time, Dick Devine was the Cook County state’s attorney, but it was one of Devine’s prosecutors, Scott Cassidy, who recommended that Gargiulo not be charged. The reasoning emerged in statements to the media following Gargiulo’s eventual arrest in L.A.—and in answers to several questions I e-mailed to Sally Daly, the spokeswoman for the current Cook County state’s attorney, Anita Alvarez. (Cassidy refused requests from Chicago to speak publicly about the case.)

The state’s attorney’s office says that procedures used to gather the DNA from Tricia’s fingernail clippings made it impossible to determine whether the genetic material came from the tops of the nails or under them. Because of that, the office says, experts have not been able to rule out the possibility that the DNA found its way onto Tricia through casual contact—particularly since Gargiulo was known to have occasionally visited the Pacaccio house.

Prosecutors also point to an incident that occurred the day before the murder. Tricia had been walking down her street on the way to her boyfriend’s house when Gargiulo, driving his father’s van, pulled up and offered her a ride. Scott Olson, Gargiulo’s friend and bandmate, was in the passenger seat.

Even though Olson insists there was never any physical contact between Gargiulo and Tricia—and says he was willing to testify to that in court—prosecutors remained unwilling to bring charges. For starters, they say, Olson was equivocal when initially interviewed by police. (When I talked to Olson, he acknowledged that it was possible the two somehow came in brief contact, but added, “I never saw them touch. That’s what I can testify to.”) Prosecutors also argue that Tricia could have gotten the DNA on her by brushing up against something in the van. The bottom line, the office says, is “there are no lab analysts who are willing to take the stand and testify in court that the DNA gathered could not have come from casual contact.”

To the Pacaccios—and to the L.A. detectives who have looked into Tricia’s murder in support of their own case—the argument is hogwash. Even if Tricia had brushed the back of the seat and somehow picked up some of Gargiulo’s DNA, she took a long shower the next night before going out, they say. What’s more, witnesses told police that the night of her murder, Tricia came into contact with some two dozen of her friends, including her boyfriend, whom she both hugged and touched. Yet only Gargiulo’s DNA was found on her.

In a corporate-looking suite of offices just outside of Los Angeles, Mark Lillienfeld, a detective with the office of the L.A. County sheriff, shook his head when I asked him about the casual contact theory. “Is it possible?” he said. “Yes, and it’s possible that Barack Obama is going to appoint me head of Homeland Security and Cindy Crawford is going to leave her boyfriend for me. I haven’t gotten my letter from the president, and Cindy Crawford isn’t banging at my door.”

The standard necessary to convict, Lillienfeld says, is not proof beyond a shadow of a doubt, but beyond a reasonable doubt. “I think sometimes people are unwilling to take a risk professionally,” he says. “Every prosecution is a risk. Sometimes you’ve got to do the right thing and not worry about the consequences”—such as potentially losing a case. “To me, [charging Gargiulo] is a no-brainer.”

Small agrees. “Stupid me, I thought they [were] going to arrest him—confront him with evidence and see what he had to say,” says Small. “That’s what I thought, but it didn’t work out that way.” Reed is equally blunt in his criticism. “It troubles me enormously,” he says. “Those young women in California are dead because we dropped the ball.”

“Some police officers, family members, and journalists have second-guessed or criticized the state’s attorney’s office for not bringing charges in this case, and they are certainly entitled to their opinions,” responded a spokesperson for the Cook County state’s attorney before the new witnesses came forward in late May. “We understand and to some extent share those frustrations. But ethical guidelines prohibit the charging of a case without evidence in hand that will enable us to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Two years after the DNA match, on the night of December 1, 2005, a killer climbed through the kitchen window of an apartment in El Monte, a working-class suburb of L.A. The striking young woman who lived there, an aspiring model named Maria Bruno, had been uneasy in the days leading up to that night. A “weird guy” had been watching her, she told friends. Once, the dark-haired man, wearing a hooded sweatshirt and a baseball cap, had followed her into her apartment without her realizing it, according to witness testimony. A few seconds later, he backed out, saying, “OK, I’m leaving,” and she shut the door in his face.

Bruno was attacked sometime that December evening. The intruder grabbed a butcher knife on her kitchen counter and, in a frenzied attack that police believe may have spanned several minutes, stabbed her 17 times, causing deep wounds to her chest, arms, and stomach. As with Ellerin, Bruno’s throat was slashed so deeply she was nearly decapitated. The killer also sliced off both of Bruno’s breasts and put one of them in her mouth. Several of the wounds were inflicted after Bruno was dead, Lillienfeld says. As with the Ellerin case, the killer appeared to have changed Bruno’s body position. Also, like the Pacaccio and Ellerin murders, both robbery and sexual assault were ruled out. Like Small, Lillienfeld thought the attack had all the markings of a serial killing. Unfortunately, he had little to go on beyond a description given to a sketch artist of a young, good-looking, dark-haired man and the “weird guy” who had been paying attention to Bruno. Lillienfeld did discover one intriguing piece of physical evidence: a blue medical bootie, found outside Bruno’s apartment.

Three years later, on an April night in 2008, Michelle Murphy, a petite, beautiful 28-year-old blond, finished her laundry, turned out the lights in her Santa Monica apartment, and went to sleep. She awoke sometime after midnight in a fight for her life. A man wearing a hoodie and a baseball cap was straddling her body, stabbing her in the chest. She grabbed the blade, the steel slicing her palms. She kicked wildly at the man, her blood-slicked body making it hard for him to hold her. At some point, the man cut himself, and Murphy, seizing the moment, pulled her feet to her chest and vaulted the attacker off of her. The man fell against the wall. “I’m sorry,” he said, and staggered out. As he fled, he left a trail of blood. The spatters led down Murphy’s steps and across the alley toward an adjoining apartment complex. It was the same complex, detectives later learned, where Michael Gargiulo—by then married to a woman named Ana Luz Gonzales—had lived since around 2007. His second-floor apartment, in fact, had a direct view across the alley into Murphy’s.

For Sergeant Rich Lewis of the Santa Monica Police Department, the next step was obvious: Test the DNA collected from the blood left at the scene, enter it into a national police database, and hope for a hit. A month later, he got it. The attacker’s DNA was the same as that found on the fingernail clippings of a 1993 murder victim in Glenview, Illinois, named Tricia Pacaccio. The DNA belonged to Michael Gargiulo.

The Santa Monica Police Department arrested Gargiulo in a Rite Aid parking lot on June 6, 2008. A search of his car produced a bag with some tools and blue medical booties. He was charged with the attempted murder of Michelle Murphy.

Soon other dominoes began to tumble. The DNA match made Lewis think of a murder he had discussed months earlier with Lillienfeld—the Bruno slaying. On a hunch, Lewis called Lillienfeld, who, armed with a name and a face, began reinvestigating Bruno’s death. He discovered that Gargiulo had lived in the same complex as Bruno and, according to witnesses, had made several statements about how attractive he found her. Lillienfeld returned to Gargiulo’s apartment, now vacant, hoping to find some remnant of physical evidence. After searching the rooms, he checked the attic. There, in a plastic bag, was a single medical bootie—the same make and manufacturer as the one he had found at the Bruno murder scene. A test of skin cells on the bootie matched the DNA to that of Gargiulo.

With DNA linking Gargiulo to two murders and one attempted murder, Small and Lillienfeld had enough evidence to file their own cases with the L.A. district attorney’s office. Already in jail for the alleged attempted murder of Michelle Murphy, Gargiulo was charged in September 2008 in the Ellerin and Bruno killings. After a two-week preliminary hearing in June 2010—at which the judge allowed evidence of the Pacaccio murder to be introduced—Gargiulo was ordered to stand trial. At the time this story went to press, a trial date had not yet been set. Among those expected to testify was the actor Ashton Kutcher, who would help establish the time of the Ellerin attack.

If a Los Angeles judge allows it, Lillienfeld and Small say, the Pacaccio murder will be recounted when Gargiulo is tried for the killings of Maria Bruno and Ashley Ellerin, as well as the attempted murder of Michelle Murphy. As with the preliminary hearing, the evidence would be introduced under California’s “prior bad acts” statute. The law allows allusions to crimes that are substantially similar in motive and method to the offense that’s been charged, provided the judge rules there’s a reasonable likelihood the defendant committed both crimes. A similar law does not exist in Illinois.

As tough as they have been on the Cook County state’s attorney, the L.A. detectives and the Pacaccios both praise the efforts of Lou Sala and the other Cook County sheriff’s cold case detectives who continued to investigate Tricia’s death. “Since I started working with the Cook County sheriff’s police in 2002, the guys that I’ve dealt with and worked with are first-class detectives,” says Small. “I have nothing but good things to say about them.”

As for the state’s attorney’s office, Lillienfeld, Small, Reed, and Baldwin remain harsh critics. “All I know is, if I were [the Pacaccio] family, I would be beyond outraged,” Small says. “Because I know what the Ellerin family went through. All those years of being patient and wanting to know what happened to their daughter.”

Nightfall looms in Glenview when I pay my last visit to the Pacaccios. The mother and father, sitting at the kitchen table, are weary after a long day of work. I glance again at the door that leads to the stoop where it happened, where Rick found his daughter, the entrance that they no longer use. I look back at their stricken faces.

The Pacaccios are grateful about the late May development—the two new witnesses who have come forward saying that Gargiulo confessed to killing their daughter. They are pleased at the thought that justice may finally be at hand for the girl whose room they keep exactly as it was 18 years ago. But for them the notion of closure—or forgiveness—is as foreign as the traces of Gargiulo’s DNA found on their daughter’s fingernails.

“There is no such thing,” Rick says, his voice rising. “What was done to this family can’t be erased. That will stay with me until I die.”

For a moment, they are both silent. They look at me with beseeching, red-rimmed eyes. Outside, thunderclouds gather. The rain comes in torrents.