The past: his prime. Sabin is breathing new life into vintage television.

This—the following few thousand words—is about him. Which is also to say that this is about This, the name of the Chicago-based television network he created late last year that is already available to more than 60 percent of the country. Any story about him must also include U and Me—or, given one’s preference, U and Me and Me-Too. After all, nearly everything that comes next has to do with Me. (Doesn’t everything?) Although to be fair, a true and total accounting of his work (recently, at least) involves U, Me, Me-Too, and This. But not so much yet about That. At the moment, he is unsure what to do about That. (More on That later!)

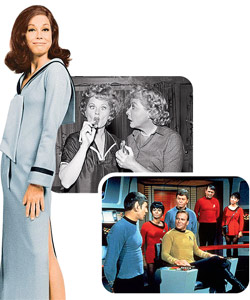

For now, meet him—52-year-old Neal Sabin—nationally revered broadcasting impresario. While he lives in the present, he works almost exclusively with television from the past. On his stations, you will find more than 100 vintage TV series that stretch, in generational terms, from the start of the baby boom to the close of Generation X. The Jack Benny Show; Perry Mason; Alfred Hitchcock Presents; 77 Sunset Strip; The Man from U.N.C.L.E.; Bewitched; Barney Miller; Police Woman; The Incredible Hulk; Cagney & Lacey; The A-Team; and so on.

Per official duties as executive vice president of Weigel Broadcasting, Sabin oversees, programs, and invents and nurtures the personality (or “stationality,” in his parlance) of four local stations. The U (as in WCIU–Channel 26) is his general-market station with urban skew and freshest programming choices (The Bernie Mac Show, The Insider, selected Cubs, White Sox, and Bulls games). Meanwhile, Me-TV (as in “Memorable Entertainment”) and its spinoff, Me-Too, are his retro offerings. Their promos arrive in a thunderbolt of mock egocentrism, unfurling a breakneck cavalcade of iconic television characters celebrating themselves: “Who—me?” asks Arnold Jackson (Diff’rent Strokes). “Goodness me!” shouts Shirley Feeney (Laverne & Shirley). “Me! Me! Me!” whines Lucy Ricardo (I Love Lucy). “Woof!” barks Lassie (Lassie). The superimposed translation: “Me!”

Venture number four and Sabin’s latest brainchild, This, is the movie network that he runs in partnership with MGM—every flick therein from the MGM vault. All four stations are available both to the noncable world—no monthly purchase required!—and to Comcast and RCN subscribers; DirecTV and the Dish Network, however, offer WCIU and Me-TV only.

As for sequence, Sabin’s success with WCIU begat Me-TV in 2005, which begat Me-Too in March of last year, which begat This eight months later. WCIU itself originated in the 1960s as a UHF outlet—typically hardscrabble, ever-disappearing stations infamous for airing the acutely offbeat and niche ethnic programs. Three choice listings from WCIU’s unruly formative years: Bullfights (“Entire corrida of six fights from the Plaza Monumental in Mexico City”); The Phil Lind Show (“Phil looks at new methods for treating the mentally ill and talks with former mental patients”); and The Swinging Majority (“Art Roberts hosts a teen-dance show”). Still under family ownership more than 40 years after its inception, Weigel Broadcasting stands as the last independent television outfit in the city and one of the last in the country. So while the network affiliates in town (WBBM, WMAQ, WLS) blare forth with new, expensively created fare, Weigel’s channels beam with Sabin’s intuition and pluck. “Neal is doing the best television in Chicago with the least amount of resources and the toughest obstacles,” says the former Chicago Sun-Times columnist and local television/radio sage Robert Feder.

Some compelling anecdotal evidence: First Lady Michelle Obama told the Daily Show host, Jon Stewart, during the presidential campaign that she ignored the debates in favor of watching The Dick Van Dyke Show. She never said on which channel exactly, but it airs only in Chicago—courtesy of Sabin’s ability to persuade mystified big shots at the William Morris Agency to allow him to showcase it locally—and approximately in the time slots during which the candidates were having at each other. (The first lady’s press office did not respond to inquiries.) Carl Reiner, The Dick Van Dyke Show’s creator, says, “A couple of weeks after she made the comment, it occurred to me—she was talking about the fact that your guy Sabin made it possible for her to enjoy the show on those nights.”

On the flip side, some hard empirical evidence: WCIU’s afternoon block of court shows (Judge Mathis, People’s Court, et al.) often put the station number two in the market during the daytime, behind only the ratings supernova WLS–Channel 7. And per Nielsen’s November 2008 sweeps book, Me-TV tied or bettered in overall area viewership the cable networks Animal Planet, Bravo, CNBC, Oxygen, Sci-Fi, the Cartoon Network, the Travel Channel, and TV Land, a conceptual cousin that lately has decided to forgo some of its throwback slate for newer series (the reality show High School Reunion, for instance) aimed at a younger demographic. In raw numbers, about one out of every three Chicago households watches Me-TV for at least 15 minutes a month.

“My fantasy is that Channel 5 will let Neal hire me to host an occasional all-night special [on Me-TV] where I’m sort of a video DJ playing episodes from my favorite shows and commenting during the breaks—you know, taking phone calls, reading e-mails,” says Bob Sirott, WGN radio midday host, NBC5 news anchor, and ardent devotee of The Honeymooners (Me-TV, weeknights, 11 p.m.).

* * *

Photograph: Lisa Predko; Television provided by www.predicta.com; Stylist: Lisa Perry; Grooming: Karen Brody

|

|

He makes television from an expansive former print factory due east of Oprah’s Harpo headquarters in the West Loop. Persistent arm-twisting of City Hall earned the building the address of 26 North Halsted (as in Channel 26)—a designation not exactly reflective of its location on the city’s grid. An oversize winding staircase takes visitors from the street-level entrance up to Weigel Broadcasting’s second-floor administrative nerve center. In the Spartan lobby, a movie theatre–style popcorn machine provides snacks for waiting guests. Publicity photos of the stations’ marquee personalities hang everywhere. Chief among them—Svengoolie (a.k.a. Rich Koz), the comically greasepainted and bewigged horror movie host whose fabled program Sabin resurrected in 1995. (Fourteen years later, it continues to air every Saturday night on WCIU.) “Neal jokes that the only reason he keeps me around is because I remember all of the comedy lines that he uses from old TV shows and movies,” Koz says. The Svengoolie set—imagine the main room at Zanies if it were relocated to purgatory—is kept safely in the concrete bowels of the Weigel building, where all original programming is shot.

Like the rest of the premises, Sabin’s office is awash in blue-collar décor and ethos. His desk, chair, and guest accommodations (small couch, coffee table, stack of newspapers) are Ramada Inn basic. On a nondescript bookshelf across from his desk sit a quintet of 15-inch television monitors (sound down, incessantly glowing), where his eyes stray often and which occasionally spark his innate local pride. “It’s interesting to watch the opening of The Bob Newhart Show,” Sabin tells me when one screen flickers with a nightly Me-Too broadcast of the droll comedian’s first sitcom, set in Chicago. “Marshall Field’s is gone. The Wrigley Building is still there, but the National Association of Realtors Building has been redone like three times.” In his Lake View dwelling, nearly every room comes complete with a television set (nine in all). He watches them as might a normal televiewer solely when they are tuned to the premium cable channels (HBO and Showtime, to be precise, and the shows Weeds, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and Dexter specifically). “There are no commercials in those shows,” he explains. “When I watch shows with commercials, I’m writing down all of the sponsors to see if they’re buying ad time on our stations.” He makes it a point not to watch his stations before bed for fear that any on-air blunder (usually perceptible to him alone) may render sleep fitful and his blood pressure elevated.

He is aided, abetted, indulged, enabled, and, most important, financed by the Shapiros, who have owned Weigel Broadcasting since the late 1960s. Howard Shapiro, the 83-year-old paterfamilias, took control of WCIU from John Weigel—father of the late sportscaster Tim Weigel and tsunami of tumult—soon after the station launched. Until Sabin arrived in 1994, it remained the province of stock-market fanatics and telenovela enthusiasts—its format a hybrid of business, Spanish, and foreign-language programming. Howard’s erudite son Norman tasked Sabin with ameliorating the family’s chronic format challenges, luring him away from Channel 50, where, as whiz kid program director, Sabin had spent the previous 11 years. One standard (and affectionate) Howard Shapiro quip: “Meet Neal Sabin. He is making me a millionaire. I used to be a multimillionaire.” Today, both the Shapiros and Sabin are Midwest media moguls; Weigel Broadcasting also controls seven other regional television properties (four in Milwaukee and three in South Bend) in addition to the four stations here in Chicago. The total number of people in their employ—about 240.

When fashioning business strategy, Sabin favors the wisdom of Looney Toons characters over Sun Tzu or Jack Welch. To wit, at the edge of his desk a snarling visage of Daffy Duck demands, “Bigger. Better. Faster. Cheaper.” And when setting priorities, Sabin often considers a line from an old Bugs Bunny cartoon: “Is this trip really necessary?” He reasons, “I’m probably the only person who runs a TV station that has a Bugs Bunny–as–Carmen Miranda cookie jar in his office.” Sans cookies, the neon-bright jar shares a shelf neatly lined with ratings books. Wherever Sabin goes, ratings seem to follow. He scored his first detectable numbers with a music video show in the nascent days of Channel 50. Ever since, the daily Nielsen tallies have been his dirty, horrible, no-good vice. “The ratings are my drug,” he says. His highest marks—past or present—still stir within him a warm delirium. (He recites them so often that it can inspire an altogether different delirium in those around him.)

One day he pledges to me that he will write the book Everything I Needed to Know I Learned from the Three Stooges. “To this day Moe’s words, ‘Quiet, numbskulls, I’m broadcastin’,’ are far more memorable than those of my radio-TV-film mentors at Northwestern,” he swore in a guest column he wrote for the Chicago Tribune in 1993. Like Curly, he sports a nearly bald dome. Whiskers, though, perpetually cover half of his face. He and the chief Stooge, Moe Howard, share a beleaguered leitmotif. “When did you first feel successful?” I ask. “Soon, I hope,” he responds half seriously. As a result, he demurs reflexively. His most cherished career artifact—an elegantly framed replica Superman cape—is kept at home rather than the office. The Shapiro family gave it to him for his 50th birthday. The accompanying card read, “For us, the ‘S’ stands for ‘Sabin.’” He has lived life entirely in the northern regions of the city and beyond—growing up in Skokie and taking up postcollegiate remodeling projects in Roscoe Village, Lincoln Square, Evanston, and, now, Lake View. He cohabitates there with his longtime partner Jeff Jacek, a senior corporate global compliance auditor at Abbott Laboratories. If the television thing hadn’t worked out, Sabin is certain he would be selling real estate—probably happily.

Worry jolts him awake every morning at exactly three. “People always tell me not to take things personally, but I can’t figure out how to divorce myself from work,” he says. “How do I not be personally hurt when we’re not doing well?” This could be why the other piece of advice everyone gives him is “Try yoga.” He borrows further life wisdom from the anthem to the guilty-pleasure film Flashdance, “What a Feeling.” Its signature lyric: “Take your passion, and make it happen!” “That’s my corny theme song, because that’s what I do—take my passion and make it happen,” he says.

Regarding that passion, his five-foot eight-inch frame was quite possibly hard-wired with coaxial cable at birth. A common occurrence throughout his childhood: “I broke the tuner on my parents’ old Motorola furniture television so many times, switching between all of the channels and shows I wanted to watch, that it got to the point where the repairmen took the set out of the house because they wanted to try to better understand what I kept doing to it.” And: “My father was a corporate attorney who traveled a lot for business. I would ask him to bring back TV guides from the cities he went to so I could see the lineups that other cities had. Then I would write them all down and make up my own lineups. I even made up some of my own shows—a talk show or whatever. This was when I was ten years old.” Two years later: “My parents helped me start a business showing cartoons at kids’ birthday parties. I would watch the kids’ reactions to different cartoons as they were shown, and I’d note which shorts got the best reaction. I’d revise the order of the cartoons so I’d deliver on my promise to the moms—‘One hour peace and quiet’ during the party.”

Says Feder, “That’s what he’s doing today, only it’s a much bigger projector, and he’s got a lot more cartoons.”

* * *

And now, a word from the competition: “I guess this is unusual—me singing the praises of my competitor,” says Ed Wilson, president of Tribune Broadcasting, owner and operator of WGN locally and 22 other television stations nationally. (Chicago magazine is also a Tribune Company holding.) In Las Vegas a week or so earlier at the massive annual industry gathering NATPE (the National Association of Television Program Executives), Wilson expressed similar admiration for Sabin during a lunch panel entitled “How Broadcasters Thrive in This Economic Climate”: “I take my hat off to Weigel in Chicago. We watch them every day, and we hope that we can emulate them.” Later he confided to Sabin, “Everyone is rooting for you, Neal.” Wilson tells me, “He’s done a very good job of creating brands. In this new world of 300 channels, you’ve got to have a brand. And when you go to Weigel’s channels, you immediately get a feel of an attitude and brand.”

* * *

Photography: (The Mary Tyler Moore Show) © Twentieth Century Fox. All rights reserved, (I Love Lucy and Star Trek) © Paramount Pictures

|

|

This much is certain—he is being closely studied at the moment, which is fast becoming the moment of Neal-TV. In broadcast annals at least, the moment is most historic. On June 12th, the next television epoch officially dawns—the much-discussed post–analog age. A brief digital TV primer: For cable and satellite customers, nothing will change. But for the cable-less, who possess a mere television and standard digital converter box (free with government coupon!), a new TV galaxy will open, complete with clearer picture and more channel selections, each network affiliate and over-the-air broadcasters such as Weigel able to beam extra “subchannels” into local homes along with their flagship feed.

Because expanding the television universe further seems needless and burdensome, many planned subchannel offerings are the TV of Dullsville. Currently, WMAQ has a weather map. WLS has a repeat of the nightly news. But Sabin saw this unstoppable future some time ago—okay, around the year 2000. To arm himself properly for what he was sure would come next, he began readying his Me-TV time warp, which ultimately became WCIU’s first subchannel and which debuted on January 1, 2005. (In noncable households, Weigel’s stations arrive as a package deal—WCIU appearing as Channel 26, Me-TV as Channel 26.2 in the revamped television lexicon, Me-Too as Channel 26.3, and This as Channel 26.4.) “Me-TV is our way of being different from other stations,” he says. “Even the cable networks are shying away from older shows because it’s not demographically desirable. But I think that is a real blunder because there are so many baby boomers out there who are familiar with them.”

The Me-TV lineup on a random Saturday—Get Smart, Black Sheep Squadron, the original Battlestar Galactica, Buck Rogers, Knight Rider, and The Greatest American Hero. Sabin excavated each from its Hollywood studio tomb shrewdly and furtively. “When I would buy a major acquisition for WCIU such as The Doctors, I’d also say, ‘Let’s look in the library,’” he says. “A lot of that stuff, I had to tell the syndicators, ‘It’s there! You own it! Find it!’”

“At one point, I was selling him the rights to King of Queens for WCIU,” testifies Tom Warner, formerly of Sony Pictures Television and currently executive vice president of Litton Worldwide Distribution. “He kept pushing King of Queens aside to talk about renewals on all of this library product as well as picking up obscure library shows such as The Flying Nun. I was thinking, ‘What’s going on here?’ But eventually all of that became Me-TV. I’ve told him, ‘You should be working for Warner Bros. because you know more about their library than they do.’” Sabin’s surplus of shows is such that in March 2008 he launched Me-Too. “That’s right; now there are two Me-TVs chock-full of classic TV day and night,” decree the promos.

He gives careful consideration to the arrangement and packaging of his bounty, thus setting apart his branded nostalgia trip from others available via download (on Hulu, for example) or special-edition DVD set. On Me-TV and Me-Too, black-and-white noir (Peter Gunn, jazz-loving L.A. private eye) is paired with other black-and-white noir (Naked City, the gritty exploits of New York City cops). “Black-and-white is a dirty word to anyone else,” says Feder. “But Neal celebrates it.” Any Technicolor disturbance during this slate, dubbed “Sunday Night Noir,” is considered blasphemy—except, of course, for commercials, for which an exception is made since they pay the sacrosanct freight. (As a bonus delight, Sabin mixes in retro commercials such as memorable Dr. Pepper and Coca-Cola sing-along jingles.) Me-TV’s funny business is also as the television gods have ordained. Madcap workplaces (The Bob Newhart Show, doctor’s office) are bundled with other madcap workplaces (The Mary Tyler Moore Show, television newsroom). Genres and eras are betrayed only when Sabin’s gut orders it so. “I put on The Odd Couple after The Honeymooners because there’s something about the Ed Norton/Ralph Kramden interplay that’s sort of like Felix and Oscar,” Sabin explains. “It’s a different era and a different setting, but it just felt right.” Short of common theme or time period, things can get straight-up Pavlovian. For instance, Carson’s Comedy Classics once aired on Me-TV every weeknight at 10:30 p.m., the exact time at which Johnny Carson had crossed through a multicolored curtain to a bowing Ed McMahon. “He does more than just throw on a bunch of reruns,” says Phil Rosenthal, the Tribune media columnist. “He’s more of a showman than that. He’s a better producer than that. And he’s a better marketer than that.”

* * *

About his regularly scheduled programming: “There are certain shows that we have on Me-TV such as Route 66 and Rat Patrol that don’t add exponentially to what we’re doing, but they do add to our credibility of being a place for truly classic television. . . . I run That ’70s Show on Me-TV because in certain time periods, I need a younger demographic. And if that demographic sticks around, I can bring them into the classic television tent. . . . With people 50-plus, we rock! . . . I like to remove shows from the schedule before they burn out. I call it The Mary Tyler Moore Show way of doing things—leave on top; don’t run it into the ground; make people want more. . . . I did well with Police Woman at Channel 50. Men like this one. Angie Dickinson still works for them. For a while, I had In the Heat of the Night next. But the numbers dropped. So I said, ‘What do I have in the library that’s in the cop drama category and appeals to men?’ Easy—Charlie’s Angels. . . . Lately, Leave It to Beaver has been one of Me-TV’s strongest shows. Sometimes it even beats WCIU in women and comes in number two or number three in the market with women. Leave It to Beaver! . . . I like The A-Team. No one will ever spend that kind of money to blow up cars and make a live-action cartoon again. It doesn’t do that well, but it’s traveled with me. There will probably be a set of A-Team tapes in my grave.”

* * *

Now let us turn our attention back to That, as in the nascent station on the drawing board, whose content he continues to plot. Already the copyright has been secured by the Shapiros and merely awaits the Sabin stamp. After all, he muses, “That is a classic!” Of course, such proclamations are endless for all of his stations—exactly his aim. “‘Stay here for This!’” he declares giddily. “‘This is a great channel!’ ‘Have you seen This?’” Better still, he adds, “Every time my competitors use the words ‘you’ and ‘me,’ I’m sure it isn’t fun.” Even within his own empire the names can cause trouble. “Do you like the idea conceptually?” Weigel Broadcasting’s director of marketing and promotions, Molly Kelly, asks him during a departmental meeting a few weeks ago.

“Yeah,” he responds.

“Me, too,” she agrees.

“Not Me-Too!” he scolds with faux outrage. “We’re talking about WCIU now!”

A familiar resignation fills her voice. “It gets so confusing here sometimes.”

Photograph: Lisa Predko; Television provided by www.predicta.com; Stylist: Lisa Perry; Grooming: Karen Brody