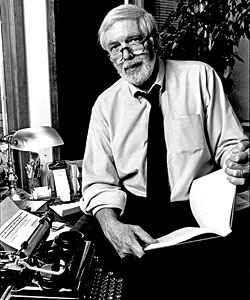

Curt Johnson: “It’s my magazine.”

Last year, in her acclaimed biography of the writer Raymond Carver, Carol Sklenicka zeroed in on the little Chicago literary magazine December, which had published Carver during his long, impoverished apprenticeship. Sklenicka also introduced the magazine’s publisher, Curt Johnson, as the great champion of Carver—and of struggling would-be writers everywhere.

I consider myself fairly knowledgeable about Chicago’s literary past, but I had never heard of Johnson, who died in Highland Park in 2008. It turns out I had much to learn about this remarkable character, a variation on the archetypal writer/editor who publishes relentlessly but lives in virtual obscurity. Holding down journeyman writing jobs by day, Johnson turned literary at night. Shrouded in tobacco smoke and seated in front of a typewriter or yellow legal pad, he composed novels, essays, and scores of short stories. From 1962 until his death, he also oversaw December: A Magazine of the Arts and Opinion, as well as books released by his December Press.

For the most part, the literary establishment ignored Johnson, and that (to use his own expression) pissed him off. It especially irked him that Chicago turned its back on him, though time and his own quirky humor eventually tempered his anger. Says his friend and collaborator R. Craig Sautter, who teaches at DePaul University: “Curt would find it infinitely amusing that Chicago magazine is writing a story about him after he’s dead.”

* * *

In his 2004 memoir, Little by Little, or How I Won the War, Johnson recalled a boyhood that was both “nothing remarkable” and “idyllic.” He was born in Minneapolis on May 26, 1928, and grew up in a white two-story house on Minnehaha Avenue not far from the Mississippi River. Money was tight—Curt’s father, an employee of the Ralston-Purina Company, took some Depression-era pay cuts—but there were regular visits to the state fair and the Walker Art Center, and, occasionally, movies and big bands at the Orpheum Theatre and chocolate malts at Bridgeman’s. At school, teachers praised the boy’s academic skills, which left him with the impression that he was (as he later wrote) “truly a superior child.”

But the persistent dark circles beneath Curt’s eyes hinted at a less rosy reality, one colored by Lutheran guilt, the Nazi threat in Europe, and the boy’s inability to meet the high expectations of his mother. “In later years he was consistently trying to frame her as being a really good mother,” says Johnson’s daughter, Paula. “But it was clear she had been an extremely frustrated person and so hard on my dad. She was just very unhappy and didn’t hide it.”

After two years in the navy, Johnson earned a bachelor’s in English and a master’s in American civilization at the University of Iowa. While there, he occasionally stopped by the famous Iowa Writers’ Workshop and picked up the students’ stories. “I’d take a copy home and read it and almost always say to myself, ‘I can do better than that,’” Johnson recalled in later years. “Eventually I had to put up or shut up.”

Following graduation, Johnson lit out for Chicago with his wife, Jo Ann Lekwa, whom he had met in college. “She wowed him,” says Paula. “She was one of the most beautiful people my dad had ever seen.” A writer and editor, Johnson landed at Popular Mechanics, which in 1954 published his first book, How to Restore Antique and Classic Cars (written with George Uskali).

After their son, Mark, was born, in 1956, the Johnsons moved to Western Springs. “We had this funky house, built in the late 1800s,” recalls Paula, who was born in 1959. “My parents were the great unknowns in the community,” she says. “They didn’t go to church, didn’t go to school functions”—but when their elderly neighbors wanted a patio, Curt Johnson built them one.

Over the years, Johnson worked for Britannica Press, the textbook company Scott Foresman, and the conservative publisher Regnery Gateway. He wrote a couple of chapters for The Chicago Manual of Style, composed ad copy touting tchotchkes for the Bradford Exchange, and spent two years as a staff writer for the lurid Candid Press. Most of the time he worked as a freelancer (as did his wife, doing editing and indexing jobs), and he often rode the Burlington commuter train downtown to meet with employers and clients. Like other writers, journalists, and ad execs, Johnson hung out at Riccardo’s, the Wrigley Building Restaurant, the Billy Goat, and O’Rourke’s. Eventually his drinking got out of hand, and he occasionally got into alcohol-fueled fistfights. “If someone said something idiotic or prejudiced, he’d snark back and it would take off from there,” says Paula.

All this took a toll on Johnson’s marriage, as did his adulterous trysts. (Johnson tracked the similar collapse of a marriage in his 1984 novel, Song for Three Voices.) “Those last years, when [my parents] were trying to decide what to do with one another, were very unpleasant,” says Paula. Curt and Jo Ann finally divorced in 1974, and Paula eventually made peace with her father. Her brother, Mark, told me: “Like everyone, my dad had good times and bad times. I always try to remember the good things.”

Photograph: Courtesy of Paula Johnson

* * *

For Mark and Paula, one of the good memories was the sound of their father’s typewriter late at night. Ultimately Curt Johnson would publish six novels, starting with Hobbledehoy’s Hero, a coming-of-age tale set in Iowa that Pennington Press, a new Chicago publisher, issued as its first release in 1959. Two of his many short stories garnered special accolades. “Trespasser,” about an old Arkansas squatter’s battle with the phone company, appeared in the 1973 edition of the O. Henry Prize stories, while “Lemon Tree”—described by one reviewer as a “story of sordid-sordid-sordid extramarital involvement”—found a place in Best American Short Stories 1980.

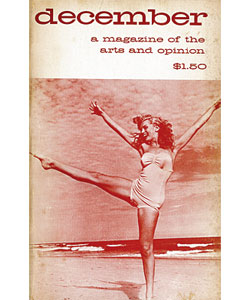

A 1966 issue of December, with Marilyn Monroe cavorting on the cover, featured Raymond Carver’s breakthrough short story, “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?”

Beginning in 1962, Johnson became the editor and publisher of December, a little magazine that had started at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1957. When the Chicago postman who had inherited the periodical could no longer afford to run it, he passed the magazine to Johnson, who nurtured it over the next 40-plus years. “It was very important to Curt to publish writers that he saw weren’t being published elsewhere,” says Diane Kruchkow, Johnson’s coeditor on Green Isle in the Sea: An Informal History of the Alternative Press, 1960-85.

Johnson invested his own money in December—by the mid-1980s, he estimated he had spent $96,000 on the magazine and taken in only $51,000—and enjoyed the freedom that allowed. “It’s my magazine,” he told a friend—the writer Norbert Blei—in a 1977 interview. “A lot of the stories are about lower-class people or men and women in desperate marital situations, a lot of them traditional in approach . . . but I happen to like that kind of story.”

December had its triumphs, publishing stories and novels by Blei, John Bennett, Jerry Bumpus, Jay Robert Nash, and others. “By the River,” an early tale by Joyce Carol Oates, appeared in 1968 and was included in Best American Short Stories 1969.

But the magazine’s greatest success was undoubtedly Raymond Carver, who in 1963 was a struggling 25-year-old father of two when he made his first appearance in the magazine with the story “Furious Seasons.” Carver published several pieces in December, including his breakthrough tale, “Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?” After appearing in a 1966 issue, it was included in Best American Stories 1967 and served as the title for Carver’s first story collection.

Johnson and Carver finally met in May 1968, when Johnson was in California attending a little-magazine conference. By then, Carver was on the December masthead as its associate editor, alongside its special editor, Gordon Lish. Over lunch, Johnson introduced the two editors to each other. A year later, Lish had become the brash young fiction editor at Esquire magazine, and one of the fresh new writers he promoted was Raymond Carver.

Johnson continued to mentor and champion Carver. In the winter of 1978, he let him use the rustic, snowbound cabin he owned near Galena—though Carver fled after a week, spooked by the place’s oppressive isolation. As Carver’s fame and income increased, the two men grew distant. They had their final meeting in Chicago when Carver, now a superstar, appeared at a 1986 fundraiser for Poetry magazine. Two years later, he died from lung cancer.

In a 1994 essay, Johnson, though of the opinion that success had had a deleterious effect on his old friend, was unstinting in his praise for Carver. “In the territory of fiction he staked out for himself he was absolutely honest,” Johnson wrote, “and in that territory no American writer can touch him. He can truly break your heart.”

* * *

After his divorce from Jo Ann, Johnson married—and divorced—two more times. Though he claimed to love women, he once described himself as a misogynist. In his 1995 novel, Thanksgiving in Vegas, he wrote: “The thing to keep in mind was that if you grew too dependent on [women], or trusted them too far, they left you in the lurch, betrayed you in some way. That much about them was predictable.”

In 1990, Johnson bought a little white house in Highland Park. He built a deck out back and installed a Zen garden. His closest companion was a big beagle named Rocky. In 2007, Norbert Blei’s Cross+Roads Press published Salud, a compilation of Johnson’s writings. When Blei visited the Highland Park home to deliver a copy, he found the once-vital Johnson a “ravaged hulk”—he had lost a lung to cancer in 1997—who forced back tears when he saw the book.

On June 9, 2008, two weeks after his 80th birthday, Johnson died alone in his bed. Paula organized a heartfelt memorial service for her father, and after he was cremated, she spread his ashes at a location she prefers not to disclose. “I admire what my father did,” she says. “I admired it as a kid, and now I admire it even more. He was very successful in seeing through what he believed in, and he didn’t compromise. And that was very cool.”

PRINTERS ROW LIT FEST

June 12th-13th

Stop by Chicago’s booth to pick up our list of the Top 40 Chicago novels of all time.

Photograph: Courtesy of Paula Johnson

Comments are closed.