Her clothes are like wearing air—air that flatters your figure and wraps you in the glamorous luxury of silver-shot tulle, python-printed lace, or acid-washed shantung. Her Italian leathers and Japanese wools are so soft and pliable that they could be used for baby bunting. The sumptuous, sensual moment when grace and function stylishly merge—that is Maria Pinto’s métier. No wonder that her studio and workspace on North Elston Avenue are filled with breezy energy and light.

In spite of her rarefied fabrics and sophisticated designs, Pinto, 51, one of the city’s foremost women’s fashion designers, is down-to-earth friendly. She wears a gray cashmere sweater, a black skirt of her own design—with her trademark intricate workmanship creating an effortless silhouette—and knee-high boots with low chunky heels that still add a boost to her petite stature. Her constant best accessories: her shoulder-length raven-colored hair and an engaging smile.

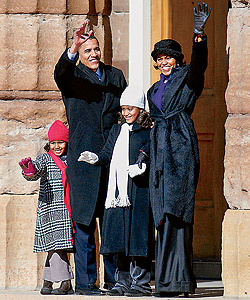

Sasha, Malia, and Michelle Obama in coats by Pinto when Barack announced for the presidency last year |

“There is a client here right now,” she says sotto voce as she leads the way past floor-to-loft-ceiling white drapes that mark off her showroom and fitting area from the design, cutting, and sewing space. The curtains billow slightly as Pinto passes by, but the guest remains anonymous. She could be one of Chicago’s high-profile CEOs or socialites who have been wearing Pinto’s creations since she started designing accessories for evening in 1991. (Like many of her clients, Pinto serves on nonprofit boards and committees, those of the Joffrey Ballet and the Art Institute of Chicago.)

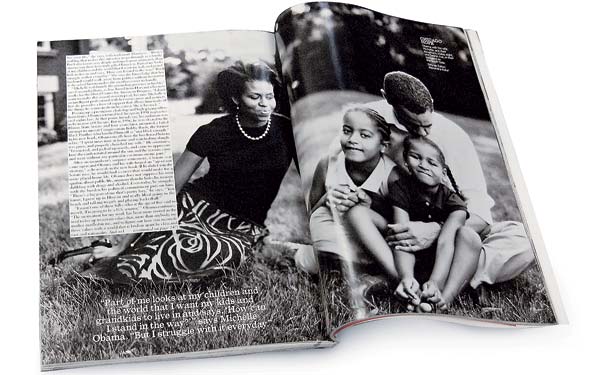

Or it could be Michelle Obama, the wife of the junior senator from Illinois and Democratic presidential candidate. She was referred to Pinto by another client in 2004, a few months before her husband was sworn in as a senator. When Vanity Fair anointed Michelle one of the ten best-dressed women of 2007, she in turn named Pinto as her designer of choice. She has been photographed for the pages of Vogue and WWD wearing Pinto’s designs. “Every designer wants to dress a celebrity,” says Pinto, who quickly admits that the connection has pulled her clothes into the spotlight. “But I’m proud that she is such a person of substance and accomplishment.” In February 2007, when Barack Obama announced his presidential campaign standing outside in the subfreezing temperatures of Springfield, his wife and their two daughters wore coats designed by Pinto—captured in a front-page photo in the Chicago Sun-Times. Michelle Obama also wore a Pinto jacket—with wide lapels and a nipped-in waist—when she and her husband appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show. Even Winfrey herself recently hit the red carpet, for the première of a Denzel Washington movie, wearing a Pinto-designed long cognac-colored leather skirt.

The time is right for Pinto—an incredible rebound from a difficult decline. In 2002, she closed her business following the embezzlement of hundreds of thousands of dollars by a long-term employee. The post-terrorist economic downturn was another factor. Pinto’s designs previously had been carried by Neiman Marcus, Bergdorf Goodman, and upscale boutiques.

A short time later, after laparoscopic surgery, Pinto developed peritonitis. She was hospitalized for more than three weeks and then bedridden in her Gold Coast apartment for six months. “It was the worst time I could have ever imagined,” Pinto says. “But I knew I was coming back. I knew it the day I closed my doors.”

Oprah Winfrey in Pinto’s Letta lamb leather skirt at a 2007 premiere |

While recovering, Pinto took painting, computer, and business classes to help her bounce back. And thanks to a group of investors and a business plan as meticulously detailed as one of her cocktail dresses, she relaunched her label in 2004. But she scaled down this time, reducing her overhead as well as the number of employees (from 30 to 18) and the venues where her designs can be purchased. (In Chicago, her accessories are now carried by Saks Fifth Avenue and Barneys, and her ready-to-wear line is sold exclusively at her Elston workspace; in New York, her collection is available at the ultrasophisticated Takashimaya.) She kept her signature concentration on eveningwear while expanding her daytime line to include lacquered linen jackets, pinstriped pants, asymmetrical blouses, and metallic-sheen trench coats.

Her designs range from $350 for a simple shell to $5,000 for gowns; her typical customers range in age from 35 to 60 and in size from 2 to 16. “I’m not about one body type,” Pinto says. “And I love creating those make-an-entrance evening dresses. But we all have daytime lives. Women need clothes that work but also look wonderful.” Pinto also made a concerted effort to rein in her drive to do it all. (She says that green tea, yoga, and a great acupuncturist have helped.)

By scaling back her business, Pinto has rebounded in a big way. Currently, her company is experiencing an annual revenue growth of 300 percent. “It is wonderful that a Chicago-based designer is being recognized as an important force in fashion industry markets like New York,” says Ikram Goldman, the owner of the internationally known Chicago boutique Ikram.

“She has come back with a bit more edge and a bit more sex appeal while keeping her luxury style,” says Stacey Jones, the fashion director of Chicago magazine. Some of her regular clients agree.

“This is some pretty sexy stuff,” says Jan Melk, a private investor whose eveningwear purchases for the past three years have been exclusively Pinto designs. “That extends into her daywear, too, like these unbelievably lightweight laser-cut leather jackets.”

“I always feel very glamorous and very sexy in Maria’s clothes,” says Melinda Jakovich, a Gold Coast realtor who has worn Pinto designs for the past five years. “She doesn’t want to just sell you a dress. She wants you to look your best.”

In May 2008, Pinto’s sales potential will increase when she opens her own 2,000-square-foot boutique, with workrooms upstairs, in the West Loop. “Today you can buy almost anything online,” she says. “So people come to you for your experience and your eye. Add a cup of espresso or a glass of Champagne and a beautiful environment, and you have a memorable hands-on experience.”

* * *

Photography: (Image 1) Erika Dufour; Hair and Makeup: Krista Gobeli

Michelle Obama, in Men’s Vogue, September-October 2006, wearing Pinto’s Simona burnt-out-organza skirt

At the opening of the restaurant Sepia in 2007: Pinto in her Trisna French lace dress and Michelle in Pinto’s Sudara silk-taffeta dress |

The experience of today is the fall 2008 collection, which will have about 60 pieces, some available in two or three fabrics. Pinto takes her inspiration where she finds it, and pinned to a wall by the cutting tables are the muses for her current vision: color photographs of nomadic tribes in Ethiopia. “Aren’t these great photos?” says Pinto. “Look at how they drape animal skins over their bodies, how they use these organic forms, like shells, as embellishment.” At first glance, nomadic tribes of Ethiopia may seem like a long reach for the fabulously chic women of Chicago and New York, but Pinto makes it work. “Of course, I’m interpreting it,” she says, showing off fabric samples of black-on-black Japanese wool, silver and gray hand-beaded chiffon from India, dark-brown leather lined with crinoline.

Then Pinto begins picking up samples from the fall 2007 collection: corded silk skirts with tiny bands of horsehair sewn into the hems so they float away from the body; cashmere and alpaca coats lined with charmeuse; and, instead of tribal shells, custom-blackened silver beads for embellishment. These designs can be mixed with pieces from her 2008 fall collection, which was inspired by the work of the sculptor Richard Serra: blouses overlaid with raw-edged chiffon squares, dresses of tulle with copper finishing, jackets with ruched sleeves, satin dresses with racy asymmetrical cutouts in back. “Whatever disposable income we can put toward clothing,” Pinto says, “I think we should get the best we can.”

* * *

Pinto was born in Chicago, near Chinatown. Her father worked for the city’s department of streets and sanitation, and her mother was a caterer. The youngest of seven children, Pinto got her first sewing machine at the age of 13. “I didn’t have any intense or special exposure to fashion,” she says. “But I was always interested in the construction of clothes. She made her own high-school prom dress: a Halston pattern with a fitted bodice and a full skirt.

In the early 1980s, Pinto’s family opened an upscale Italian restaurant at Erie and Wells streets called Sogni Dorati (translation: Golden Dreams). She felt committed to the business—her brother Silvio was the head chef, and the restaurant garnered rave reviews (it closed in 1987 when her brother became ill). But when she was 30, she decided to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and major in fine art with a focus in fashion. There she continued to develop what would become her signature style: body-conscious construction with high-quality fabrics and intensive detailing.

After graduation, Pinto moved to New York City and started working for the fashion icon Geoffrey Beene, in his Fifth Avenue shop, where she handled some of his high-profile clients, and in the design room, where she studied Beene’s style of construction. He had a medical background, and his construction was closely connected to the body’s musculature, following the line of an arm or the curve of a hip. In 1991, Pinto moved back to Chicago and started sewing. Her first projects were luxe evening wraps and scarves. She sold them by calling on stores; her first order came from Joan Weinstein, then the owner of Ultimo, the Oak Street boutique. Other city and suburban stores followed. Pinto also got orders from Barneys and Bergdorf Goodman in New York. Her accessories remained one of the top sellers in Bergdorf’s catalogs until she closed her business in 2002.

After almost two years of designing accessories, Pinto began to branch out, making jackets and outfits to match her wraps. Along the way, she translated what she had learned from Beene into flattering, entrance-worthy clothes based on draping, bias cuts, and seaming. “There are so many little tricks of cut,” she says. “It may not be a big thing, but it can make all the difference in the world in terms of having a dress look OK but not really work, and having a dress fit perfectly.”

The business started flowing, too. Pinto established a customer base among executives and socialites—people who attend at least several black-tie events a season. Her luxurious gowns of panne velvet and double-shot taffeta, her crystal-studded stoles, and her black beaded lace skirts proved irresistible to the chic set, and by 1996 Pinto had a South Michigan Avenue production center. Her collections included both couture and ready-to-wear; in the spring of 2000, she introduced a more informal Pinto Studio line. She and her two assistants made monthly trips to New York to sell her designs.

Then, at the end of 2001, there was trouble. Because of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, retailers canceled pending orders and new orders slowed dramatically. At the same time, Pinto discovered that a long-term employee had embezzled hundreds of thousands of dollars. (That person served a two-year prison term.) “I kept thinking, How could I have missed this?” Pinto says. “She seemed like a lovely lady who came to work every day. I knew I had to regroup.” In January 2002, Pinto closed her 11-year-old business. The letter she sent to retail customers at the time said that she had no choice due to “a series of setbacks . . . including embezzlement by a trusted employee and a contracting economy.”

* * *

From Pinto’s spring 2008 collection: A laser-cut leather halter wrap top lined with silk and Mercedes Italian cotton high-waisted pants |

High in a Gold Coast high-rise, Pinto’s apartment is the embodiment of Zen. The living room is filled with lacquered Asian furniture, white orchids, and two lounging cats. Her iPod is hooked up to a stereo system playing soothing music. And Pinto is serving mint tea in Japanese porcelain cups sitting on saucers that look like leaves.

Even here, in the peaceful atmosphere she has created for herself (Pinto has never been married), work is not that far away. Sometimes she watches the reality television series Project Runway. Closer at hand, in the dining room, one wall holds books covering a range of interests: Givenchy, Schiaparelli, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, anatomy, fish. Cloth-covered pin boards that display more Ethiopian photographs and fabric swatches hang on another wall. Pinto travels to Paris twice a year for fabric shows; her designs for beaded work are constructed in India. “I am a nut for fabric,” she says, picking up swatches from her dining-room table and rubbing her fingers over the material. “You have to feel this. Isn’t it the softest, most enticing fabric you’ve ever felt?”

From Pinto for spring: a Rachel pinstriped cotton shirt with square-cut pieces layered to create a collar and a Komang laser-cut leather gored skirt lined with silk |

This passion—her self-defined “hypercreativity matched by hyperorganization”—fuels her plans for the new store. “Now, with a store’s buyers picking out these pants, this coat, and certain material for dresses, my vision gets splintered,” says Pinto. “In my store, I can create an environment that presents the brand and the experience of shopping as I think it should be.” The architect for the store is Elissa Scrafano; Pinto’s brother Joe, a self-taught designer, is doing the façade; and the interior design will be by Scott Heuvelhorst. “It was an old deli,” Pinto says. “We are going to refurbish the staircase in bamboo flooring that will run up the back wall. Part of me loves richness and embellishment, but I also like clean, beautiful lines. For this space, we’re going with what I call ‘opulent minimalism.’ You know, steel and glass and comfortable, sizable dressing rooms.”

The bad times of a few years ago seem far behind her. Yet she hasn’t forgotten them. “It would be easy to get all caught up in thinking, Why this? Why that?” says Pinto. “But I try to look at what happened as lessons.”

So what has she learned?

“Not to take things for granted.” She pauses to think. “And to concentrate on what is important. Sometimes I have to rein myself in. For example, I love handbags. So I could get all caught up in making handbags. Or jewelry—I love jewelry, too. But I’m not going to do that now. It could be easy to get lost.” Sitting here, over her cup of tea, Pinto is clearly wearing her confidence. And she wears it well. “I don’t want to dilute myself and have everything be just OK. I don’t want to be too big and just passable. I have learned that I want to do what I’m doing and be fabulous.”

Photography: Erika Dufour