EDITED BY DAVID ROYKO

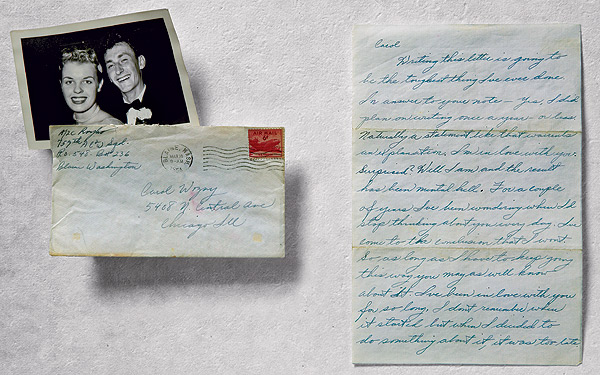

Left: Carol and Mike Royko in the mid-1950s. Right: The letter (written before Carol reverted to her maiden name) in which Royko confessed his love. View the gallery >>

A week after my father, Mike Royko, died in 1997, a slightly heavy envelope arrived with the scores of other cards and letters that had been pouring in. When I opened it, several snapshots tumbled out.

The message came from a man named Don Karaiskos, who had been my father’s roommate and buddy in the air force while they were stationed in Blaine, Washington, where my father had been sent after serving overseas during the Korean War. The photos had been taken with an old camera that leaked light, which meant the pictures were on the dark side, and also had faded a bit in the 43 years since they had been taken. But they were wonderful, showing my father back in the days when he was a skinny 21-year-old in a uniform. One of the pictures had my father standing in front of a car on a mountain road, and on the back was written, “Mt. Baker, Easter.” I made a mental note to find Mount Baker on a map.

After a few minutes, I put the pictures back in the envelope and began looking through one of the many boxes that my father had left behind. I was just beginning to realize he’d saved everything—photos, canceled checks, paintings, costume jewelry, clothing, knickknacks, everything. As I moved things around, I uncovered a smaller cardboard box containing letters, maybe a hundred or more, all neatly packed. I pulled one out and looked at the postmark: Blaine, Wash, April 22, 1954. As I began reading, the words described a day trip to Mount Baker on Easter Sunday. It provided the story to the photo I had just seen.

That degree of serendipity should have floored me, but it took a back seat to my astonishment over something else: These were the letters. THE letters. The holy grail of my nuclear family. The place where it all began. My mother had told me about them, but I had come to doubt they still existed; I had even begun to wonder whether they ever had, at least in the way my mind had held them. But here they were.

My father was born September 19, 1932, and my mother, Carol Joyce Duckman, November 21, 1934. By the time “Mickey,” as he was then known, was ten, he was secretly in love with my mother. She liked him, but not in the way he loved her. His feelings only deepened with time, but he could be painfully shy, especially in the area of romance.

She grew up to be a stunning beauty, five feet, nine inches, blonde, and possessing an intelligence and gentle charisma that attracted men by droves. He, on the other hand, was a skinny guy with a large Adam’s apple and a larger nose. That his already huge wit and mind dwarfed these physical attributes did little to boost his self-image, and he suffered the torture of being her close friend and having to listen to her talk about the positives and negatives of the various “boys” that she dated. She had no idea how he really felt about her.

In 1952, my father enlisted in the air force, and as he was about to head to Korea, he received the terrible news that Carol was getting married. His dreams of what might someday be were over. She was 17, and Larry, the man she was marrying, was a few years older, one of the many neighborhood guys who adored her.

When Dad returned from Korea, he stopped in Chicago before going to Blaine. Even though a visit to the Duckman house would have been expected—the entire family enjoyed him—he couldn’t bring himself to confront the reality of Carol’s new life. He stayed away. Once in Blaine, he wrote a letter to the Duckmans, betraying none of the anguish he felt, instead resorting to humor: “I guess I should apologize for not coming over during my leave,” he wrote, “but I lost so much weight in Korea that I thought Bob [Carol’s undertaker brother] might not recognize me and toss me in a pine box.”

Carol wrote back, apparently chiding Mick gently for not stopping over and not writing. She also revealed that she and Larry had separated and would divorce. The marriage had been a mistake. (Carol’s letters to my father have not survived.)

This was my father’s opening. He wrote back in a letter dated March 16, 1954, and for the first time, he told her the truth about his feelings.

These letters are selected and in some cases abridged from a collection of 112 letters sent by Mike to Carol between February 1954 and January 1955. The originals were all handwritten. We have not changed the original spelling and grammar.

|

Writing this letter is going to be the toughest thing I’ve ever done. In answer to your note—yes, I did plan on writing once a year—or less. Naturally a statement like that warrants an explanation. I’m in love with you. Surprised? Well I am and the result has been mental hell. For a couple of years I’ve been wondering when I’d stop thinking about you every day. I’ve come to the conclusion that I won’t. So as long as I have to keep going this way you may as well know about it. I’ve been in love with you for so long, I don’t remember when it started but when I decided to do something about it, it was too late. I was home for 30 days and at times the urge to go to you was overpowering. I drove by your house time after time but couldn’t stop. I can’t write anymore. Anything else I say would be a futile attempt to elaborate on a complete statement. I love you. I don’t harbor much hope but please answer or I’ll be forced to call you on the phone. I don’t want to do that until I hear from you. Love, Mick |

Photography: Michael Boone Photography/Courtesy of David Royko

A photo of Carol that Royko cherished while stationed in Blaine, Washington

In our day of cheap cell phones and e-mail and instantaneous communications, it’s easy to imagine the torture my father must have felt as he waited in 1954 for his letter to cross two-thirds of the continent and hers to return. But when her reply came, the message was clear: Even if she did not reciprocate his feelings in full, she did not reject them either.

Serious fans of my father’s know of his love for the tale of Cyrano de Bergerac, the man with the big nose and brilliant way with words. Cyrano wooed his beloved with prose that he provided to a callow but handsome suitor, watching her fall for a dolt because of the words Cyrano put into the other man’s mouth. Cyrano could say what he felt only when hiding from her sight. He was my father’s hero, and Dad would now follow suit, wooing Carol from 2,000 miles away. Reading his letters is to watch the die being cast as he applied, for the first time, his wit and facility with the pen to a practical purpose. My father was always pragmatic, and these circumstances brought his writing and pragmatism together for the biggest challenge of his 21-year-old life.

The letters also show a different side of my father from what the public later saw in his columns for the Chicago Daily News, the Chicago Sun-Times, and the Chicago Tribune—or, at least, a side that was rarely exposed. Though my father wrote with sensitivity, he only occasionally laid bare his tender streak. It appeared in print most famously in 1979, when Carol died suddenly and unexpectedly, and he was shaken to the core. His column, “A November Farewell,” described the end of their great love. (To read it, go to suntimes.com/news/royko and select “A November farewell.”)

These letters illuminate the beginning.

|

April 8, 1954 The ’42 Olds I mentioned is the car I recently bought. The main feature of the Olds is that it continually provides me with laughs. Last week the horn decided to blow. I was on a quiet country road when it happened and it took five minutes for me to find the cause. While I was looking, the farmer whose sleep I had disturbed arrived on the scene fully armed. He stood there yelling “Turn it off!” and his dog sat on the ground and barked. When I fixed the horn he told me to “git!” I gitted. I’ll probably be able to get three weeks leave in September. How much time will we be able to have together? I’m taking the leave for only one reason. To see you. My last leave was spent just killing time and thinking about you. When I arrive in Chicago in Sept., I’ll stop at home long enough to say Hi, then I’m going to establish squatters rights on your doorstep. |

|

April 15, 1954 The mailroom doesn’t open until 11:30 so lately I’ve been phoning the mail clerk at 10:30 to see whether I received a letter. When I called this morning he told me I didn’t receive any mail so I slumped down at my desk in as deep a mood of depression as I’ve ever been in. A few minutes later the phone rang and he said “I was only kidding, you have a letter.” The things I said to him will be left unmentioned, but I’m sure that for the sake of his right ear he won’t joke anymore. I dropped what I was doing, hopped in my car and violated half the base traffic laws in driving to the mail room. Thirty pages. The library has lost a customer. By three this afternoon the officer in my section asked me if I was trying to memorize every page so I showed him the picture you enclosed. That shut him up. I’ve worked out a pretty good schedule for reading your letter. I read it before and after lunch, while I’m working, before I go to the golf course, before I start my evening job and before I go to bed. The schedule changes in the morning because I usually oversleep and only have time to look at your pictures and bid you a telepathic “good morning.” I’ve just had a good idea. When I get home the weather should still be warm. Lets go on a picnic. For two years I have been living in a crowd. Barracks, work, planes, boats—always a crowd of people. Lets go to some quiet place where there isn’t another human being in sight. You can sit in the shade, relax, and I’ll sit and tell you how wonderful you are. Deal? Were you eight when we met? It doesn’t seem that long ago. I guess I’m the most haywire suitor that ever lived. When we were kids I used to cut my own throat by bringing you boyfriends, then I just stayed away, now when I’m across a continent I find my voice. Some people must be destined to do things the hard way. |

|

April 22, 1954 Today I discovered that anything is possible in the service. For two years I have been getting extra time off by conjuring some of the most fantastic excuses imaginable. This morning my mind was a blank so I did what every good airman knows is the wrong thing to do—I told the truth. I told the woeful creature who is my boss that I wanted the morning off to write a letter. The ridiculousness of my request must have dulled his little brain because he said OK. That’s twice in the last two days that I have told the truth in the so called line of duty. Yesterday it had the opposite effect. I met a promotion board (a group of men who’s IQs range from idiot to moron, gathered together to determine whether my mind has become stagnant enough to assume the lofty title of “sarge”) and flunked with flying colors. I spent one full hour answering questions correctly. This was easy because they don’t use any specific list of questions. They ask only what their limited knowledge allows them to ask. Finally one sly little sergeant created my downfall. He asked me if I would order one of my friends to shine his dirty shoes in the event that I were promoted. I’ve established a reputation for being non military so every man on the board knew that I couldn’t give such an order. I spent a full minute debating with myself whether to tell an obvious lie or the truth. I said “no” quite emphatically. That ended my interview and also my chance for promotion this month. In the afternoon the results were posted and I was bypassed because of “Inability to assume responsibility.” This caused the officer in charge of my section to feel that I had put a black mark on his record so he gave me a long winded lecture. I took the lecture OK but when he asked me if I planned on reenlisting I blew my stack. The profane eloquence of my answer rocked the building and unnerved him completely. Apparently he was still “shook up” when I asked him for the morning off. What did you do Easter? All the while I [was] driving up Mt Baker I kept trying to imagine what you were doing. . . . On the way up we took three rolls of pictures and I’m pessimistic about the results. I think the camera we used is the granddaddy of all cameras. It passes more light through the cracks in its sides than through the lens. The only thing that made the trip worthwhile was the effect we had on the skiers at the lodge. Everyone up there was dressed in ski togs so when we entered the lodge dressed in suits & white shirts we stood out like sore thumbs. After dinner we returned to the car, took out our golf clubs, strolled casually to the edge of a cliff, teed up the balls in the snow, hit them, and walked back to the car. Everyone stood around looking bewildered so before they could summon the men in the white suits, we departed. |

|

April 26, 1954 I have one picture that I took mainly to preserve the sight of what is laughingly referred to as the “green hornet”—alias, my car. The ornament on its hood is partially glass and at night it glows with a ghostly green light. This plus the unusual noises emitted from its engine give it a supernatural appearance at night. Sometimes, when returning to the base, I floor the gas pedal, causing it to reach its maximum speed—50 to 60. This sends the local rustics fleeing to their cabins to tell their bonneted wives that the spirits are prowling. The people up here are, by Chicago standards, pretty backward. The idea of a lively Sunday is to go clam digging. Our base is surrounded by farms and recently we had what would be called a “shotgun wedding.” Everyone is still laughing. Due to the pressure applied by his new father-in-law, the young airman involved now arises at 3:30 to milk cows and perform other chores before coming out to the base. He is from New York and had never seen a cow until his marriage. That last sentence sounds ridiculous. |

|

May 11, 1954 Six hours ago, as I was sitting down to write, sirens started wailing all over the place. It seems that someone decided that we should have a practice alert. That was at 4. Its 10:15 now and I have finished my little tour of guard duty. When I got down to the guard office I was assigned the job of guarding a little building that contains nothing. To assist me in this important mission were two apple cheeked young lads of 17, both of whom joined the AF 2½ months ago. When the three of us reached our little line of defense, I explained to these boys in my best old soldier manner that we must have a system. This system consisted of their staying on the outside and watching for any people that might be snooping around and me staying in the building as a one man reserve unit. When I explained to them that this was the system used in the battle sectors they readily complied so I entered the building, found a comfortable table and curled up for a six hour siesta. Just as I was dozing off, one of them came in and asked me what he should do if an enemy approached. Yell “halt” I said. Naturally he wanted to know what to do if the “enemy” didn’t halt so I told him to engage in hand to hand combat. When the sun went down it became very dark outside since we were at the remotest part of the base. Apparently they were afraid of the dark because every little while they would enter and tell me that they see something moving in the shadows and want to go have a look. To help ease their minds I told them pleasant little stories of guards being found with slit throats and that if they kept a constant vigil they had nothing to worry about. When we were relieved both these “heroes” looked like they had been through an attack on Heartbreak Ridge [site of one of the most brutal battles of the Korean War] and I can imagine the grizzly tales that will be written to their families this evening. One of them was so impressed with everything that he kept calling me “Sarge” and talking like one of the characters in an old war movie. Three months ago they were flighty young high school boys. Now they are hardened, calloused veterans of a harrowing combat mission. |

|

May 26, 1954 We’re having a party in the barracks. It’s a special type of party known as a G.I. party and required special equipment such as mops, brooms, brushes, soap and other cleaning utensils. This morning the lad who was assigned the job of cleaning the halls, windows and such did a 2 hour job in ½ hour then dashed off to the golf course. The inspecting officer decided that the job was incomplete so we were confined for the evening. Now everyone is calling the negligent airman names and accusing him of causing them all this work. An evening in the barracks will do them all good. By the way, I was the guilty party. |

|

June 6, 1954 One little word you used in your last letter has had me floating all over Washington. One word and I’m completely “shook up”. You called me “Hon”. Maybe you didn’t realize what an effect it would have when I read it. I was reading your letter as calm as usual. That means I was chain smoking and my heart was going at twice its normal pace, when suddenly that word hit me in the eyes. Believe me, it was as if you had been right here and kissed me. I wasn’t the same for the rest of the day and I’m afraid to read the letter again because of the unnerving effect that one word has on me. If a one syllable, 3 letter written word can effect me that much I can imagine how being with you will be. Who says I have to die to go to heaven! |

|

July 1, 1954 If ever it should look like I’m out of the running [with you], I could never make Chicago my home. It would be too painful. I’d probably get an officers commission and stay in the service. It wouldn’t make much difference what I did because I’d just be going through the motions of living. With you I think I could not only set the world on fire—I’d melt it. Most people never realize their full potential because they lack a sufficient incentive. If a person has that motivation then he’s unlimited. You’d be the incentive. I could do anything. That may sound a little over confident but I know the extent of my own capabilities and I also know the limitations of my own personal ambition. For myself I don’t want anything. I could probably go through life hitting a golf ball and wishing I had you. Every person has unused, dormant reservoirs of ability that never come into use because they lack the spark that can only be provided by some strong emotion. Love, hate, fear—In my case loving you isn’t enough. I can love you and still have no necessity for success because the love is one sided but if ever the situation changed there’s nothing I couldn’t do within reason. |

|

August 23, 1954 Carol, to me the future without you is no future at all. Life wouldn’t have any meaning. Anything I accomplished would be worthless, I’d have no incentive. I can understand why so many men have joined the Foreign Legion because of a woman. That probably sounds silly but believe me, I don’t know what I would do without you. I wouldn’t join the Foreign Legion of course but I doubt if I’d ever return to Chicago. |

Photograph: Courtesy of David Royko

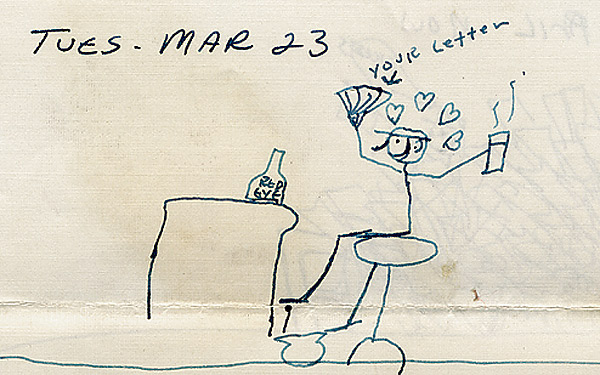

Part of a cartoon in which Royko depicts his joy at the receipt of Carol’s latest letter—and his struggles to craft a worthy reply. Click here to see the cartoon and other images.

On leave in September, Mike proposed and Carol accepted. She would come out to Washington in November and they would be married that month. After a brief honeymoon, she would return to Chicago and he to the posting at Blaine. Her agreement to become his wife did little to calm his insecurities.

|

September 23, 1954 My darling, as soon as possible be with me again. Nothing has any meaning, the world is empty without you. Life is too short to spend away from you. Write often. Tell me you love me. I can’t hear that often enough. I love you so much that if I lost you all that would remain is death. Leaving you made me realize that I couldn’t live without you. Death would be more meaningful than life. Goodbye for a little while baby. Once more I’m 2000 miles away with my love for you as my only companion. I love you, I love you, I love you. |

|

September 23, 1954 Forty minutes ago I mailed a letter and if this arrived with it I hope you read that one first. After I mailed it I noticed that I had two hours to wait for my train . . . so I called up the marriage bureau and checked with them. Baby, we can be married as soon as you get off the plane. No blood test required. I can get the marriage license, mail it to you, you fill out your part in the presence of a notary public, mail it back to me and that’s it. As soon as you arrive, we’re off to a Lutheran church for the ceremonies. When I get to Blaine I’ll check with some Seattle boys and find a nice place for a honeymoon. . . . There must be a quiet lake nearby, with a cozy cabin and a lot of solitude that doesn’t cost lots of money. This isn’t the vacation season so that shouldn’t be difficult to find. Oh my sweet, how I’m longing for you and the day you’ll arrive. I’m going to have everything prepared so that everything is as perfect as can be. My darling it will be the most perfect week two people ever had together. |

|

September 24, 1954 Everyone seemed happy to see me back. The C.O. said “welcome home”. I saluted and said “home hell! I just left home.” He thought I was joking. Back to work now. They allowed everything to pile up. |

|

September 26, 1954 I’ve been trying to read but all that’s available are recently written fiction novels and they have the same types of plots. Romance. I’m the last person who would be against romance, but baby they all sound so shallow and weak. I’d like to write our story. I wonder if it would sell. It’s got the ingredients. First we take a boy, a very mixed up boy who has a crush on a girl. The girl has already shown indications of someday being a beautiful woman. Then we take the conflicts. The boy feels inferior and never voices his love. Time passes and someone else appears. The boy accepts this because he is young and the young heal very easily and in the young there is hope. Then one day there is no longer any hope and the new wounds hurt and they don’t heal. Then the boy goes to war and he carries with him pictures. Pictures in his bag and pictures in his mind. The pictures in his bag are pretty but the pictures in his mind aren’t. Now we have a boy become a man. A broken heart and war can make great changes. He comes back and he hides. He hides from the thing he loves more than anything else. Then one day there is hope again and the hope becomes promise and the promise becomes love and love like theirs can only have one consummation—they lived happily ever after. So I could write a wonderful love story—if—I were a writer but since I’m not, the world will have to suffer along its way without knowing about us. |

|

September 27, 1954 I’ve got to pinch myself. A man can want something so badly all his life that when finally it’s within reach it’s still hard to believe. You, the girl of my dreams, the most important person in my life, you are going to be my wife. When we’re celebrating our 30th anniversary I’ll still be a bit amazed and I’ll still be the luckiest guy to ever walk the earth. |

|

October 2, 1954 Someday honey, someday, when I’m a success in other peoples eyes I’ll be asked how success is achieved. I’ll have an answer all ready. By wanting it for someone else’s sake more than for your own. All these things we want, I’d never give a thought to without you. |

|

October 2, 1954 It’s still Friday night and its been two and one half hours since I finished the last letter I wrote. After I sealed the envelope, I took a shower, shaved, and heard music coming in through my window. I dressed and walked down to the source of the music—the club. When I walked in the door, a sudden and very surprising cheer went up. It took a few seconds for me to realize that the cheers were for me. Someone handed me a drink and the ribbing started. The news that I’m getting married spread around the base like wild fire and everyone was getting their two cents in. One of the guys was making long speeches against marriage. Someone yelled “show him her picture”. It was one of the guys from this barracks and one of your sincerest admirers. I showed him your picture. He could say no more. It was a pleasant two hours. I had three free drinks, sang in a make shift quartet and to top it off, won two dollars in my favorite bet. A new lad thought he was quite a bass and was low noting all over the place. A two dollar bet was made and I left him somewhere up among the baritones—easy money. |

Photography: Michael Boone Photography/Courtesy of David Royko

In mid-October, my father wrote a wrenching letter begging my mother not to hold out hope that he could get an early transfer back to the Chicago area. “The service is a pretty cold, heartless organization and they have frightening disregard for the feelings of the individual,” he said, admitting that “480 nights [until discharge] of lying in my bed in a dark empty room and feeling like I’m living for the sake of occupying space . . . seems impossible. It’s so awful that I tell myself very often that it can’t happen but then I stop kidding myself and try to accept it.”

|

October 20, 1954 Two weeks and we’ll be married. Married! Honey, it’s all true. It’s the most wonderful thing that ever happened. It’s a fairytale in real life. Carol Joyce Royko. Carol Joyce Royko. That sounds like music. Baby, can you imagine what it feels like to have a life dream come true? To be on the threshold of a life of happiness—sublime happiness? Baby, you’ve done all this. You’ve made me the happiest, luckiest, most fortunate guy in the whole wide world. Oh sweetheart, thank you for being you. |

|

October 25, 1954 We will have the most unusual group of people imaginable in attendance [at the wedding]. I’ll tell you about them. Joe Kahwaty, a Syrian boxer from Brooklyn, 3 years of college, dark, handsome, and a very good friend. George Shoff, a card shark from anywhere and everywhere. Ermono Gurrucchi, an Italian from Connecticut, 270 pounds, 5′ 10". Ralph Peterson, best man, electronics engineer from Chicago. Bill Varns, my boss, and another officer who is a farmer from Ohio. Variety? We’ve got it. Baby, the only thing that they all have in common is that they are all good eggs, good friends, and though extremely different, they are alike in that they are gentlemen. |

|

October 27, 1954 Baby, this is going to be difficult for me to write but I’ve got to do it and I’ll explain why. Honey, I don’t want to wear my uniform at the wedding. You know how I feel about the air force. If I wore the uniform it would be hypocrisy on my part. I don’t like the AF. It’s caused me nothing but trouble. It’s separated us, it refused to transfer me, and when I’m with you, I want to be your husband, and I don’t like to think of myself as a husband while decked out in those blue rags. No one else will be in uniform and I’d feel like a fool. Baby, this wedding is the big moment of my life. Being in uniform would detract from it. . . . Honey, I’m going to wear a suit. I’ll be a nondescript looking civilian but I’ll feel a lot better. I know that you want me to wear my blues baby, but that uniform would disgust me much more than it would please you. |

|

November 1, 1954 Just received the application, the bond and your letter. Congratulations honey. Just think, one week of being Miss Duckman, Then Mrs. Royko. |

They were married on November 6, 1954. After the honeymoon, he returned to Blaine and his letters continued, but fate soon smiled upon them, although in deeply bittersweet fashion. Due to his mother’s terminal cancer, the air force showed some compassion. Dad was granted a transfer to the base at O’Hare airport. The last letter in the box is a telegram.

|

1955 Jan 14, Everett Wash |