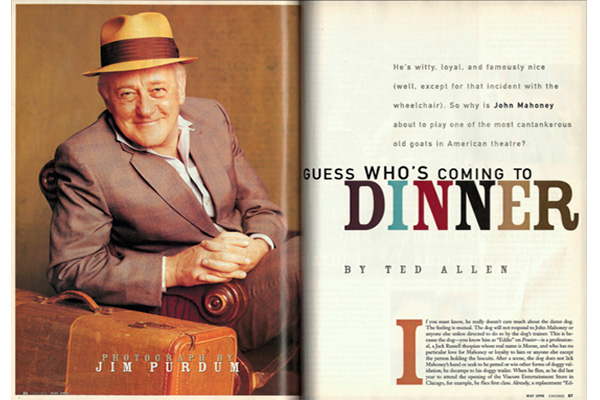

John Mahoney, the iconic Chicago actor, died Sunday at the age of 77. A late bloomer, Mahoney didn’t begin acting professionally until his late thirties, when John Malkovich recruited him to join Steppenwolf Theatre. In 1998, at the height of Mahoney's run on Frasier and ahead of his performance in The Man Who Came to Dinner at Steppenwolf, Ted Allen wrote this profile for Chicago.

If you must know, he really doesn't care much about the damn dog. The feeling is mutual. The dog will not respond to John Mahoney or anyone else unless directed to do so by the dog's trainer. This is because the dog—you know him as "Eddie" on Frasier—is a professional, a Jack Russell thespian whose real name is Moose, and who has no particular love for Mahoney or loyalty to him or anyone else except the person holding the biscuits. After a scene, the dog does not lick Mahoney's hand or seek to be petted or win other forms of doggy validation; he decamps to his doggy trailer. When he flies, as he did last year to attend the opening of the Viacom Entertainment Store in Chicago, for example, he flies first class. Already, a replacement "Eddie" is being groomed, if you'll pardon the expression, to succeed this "Eddie" when his Q-rating drops.

John Mahoney is a Tony Award–winning actor. We're not here to talk about the dog. There.

LOS ANGELES, EARLY FEBRUARY. The scene: a tatty lounge upstairs from the set of the NBC-TV hit Frasier, at Paramount Studios' Stage 25—once the home of I Love Lucy and Cheers. The end tables are covered with magazines, coffee cups, and overflowing ashtrays; the walls with hundreds of dusty, framed stills from the show; the bulletin board with news clippings and scribbled letters from fans. ("David Hyde Pierce is SO hot!!") John Mahoney perches on the edge of a battered armchair and picks at a plastic tub of tapioca pudding. He's wearing green khakis, a denim shirt, sneakers, and a Swiss Army watch. Pierce (who plays Frasier's brother, Niles, on the show) strides through the room in a flannel shirt and jeans, stops, turns, and holds up an index finger.

"Oh, John," he says. "Your hooker is here."

He continues down the hall.

Mahoney's smile is warm but he's fidgety, perhaps because he's a near-bursting fireball of energy at all times, or maybe because he feels lousy. The 57-year-old actor is recovering from a nasty case of food poisoning he will later learn came from the often-fatal campylobactor bacterium found in chicken—hence, the tapioca, which is about the only thing he can stomach. The illness has trapped him in Los Angeles when he had planned to spend his break from Frasier at home in Oak Park, as he does every month. "Unlike the rest of this cast—at the end of the workday, they go home," Mahoney says of his sessions in L.A. "I go back to a furnished rental to sleep on somebody else's bed and eat out of somebody else's dishes and sit on somebody else's chairs and basically live in an apartment that I hate in a city I don't feel comfortable in."

He is, in a word, homesick.

Mahoney's got a hell of a commute, and he's had a rough couple of weeks, but don't get him wrong: His career, and his life, have never been better. From the day in 1979 when John Malkovich plucked him from obscurity to join the fledgling Steppenwolf Theatre, where Mahoney has since appeared in more than 20 productions, he has become one of the busiest actors in Hollywood (when he's in Hollywood). Along with Kelsey Grammer and David Hyde Pierce, Mahoney has driven the Emmy-laden sitcom to its position as one of the highest-rated shows on television at the end of its fifth season. He plays Martin Crane, a widowed cop forced by a gunshot wound to retire and move in with his son Frasier (Grammer), a Seattle psychiatrist with a radio call-in show and considerably more refined tastes. Even more refined: his other son, the anal-retentive Niles (Pierce), also a psychiatrist. Whither goes Martin goes his battered BarcaLounger, patched wits duct tape, and his beloved dog, Eddie. whose trademark is to stare disturbingly at Frasier. (Eddie—er, Moose—gets as much fan mail as any of the humans or the show.)

Mahoney's touching portrayal of an aging, cranky father at conflict with his sons etched his name on the public consciousness. He had already become a familiar face on the strength of his performances in scores of feature films: She’s the One, Primal Fear, An American President, Suspect, Moonstruck, Reality Bites, Say Anything, Eight Men Out, and Tin Men, to name just a few. He holds a Tony, a Clarence Derwent Award, and a Drama Desk nomination for his work in the Broadway production of House of Blue Leaves. He recently guest starred on the critically acclaimed ABC-network drama Nothing Sacred (coincidentally, in a episode guest directed by Chicago-based David Petrarca, the resident director of the Goodman Theatre). In March, he received the Commitment to Chicago citation at the 1998 Chicago Film Critic Awards. "I feel like I should be giving 'Commitment to John Mahoney Award’ to Chicago," Mahoney told the audience at the Park West.

And on April 26th, Mahoney returns to his hometown troupe to play Sheridan Whiteside in Steppenwolf’s production of The Man Who Came to Dinner, the wacky classic by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman. After its Chicago run, he embarks for ten days in London. "I've already gotten 40 requests for interviews,” Mahoney says.

Let's stop. Must this article be yet other heartwarming recitation of Mahoney's rags-to-riches immigrant success story? (He's from England!) Of his struggles to overcome his working class Manchester accent and find his true love in the theatre? Of his decision to stay true to his adopted hometown? (He really does still live in Oak Park!) Of his famous, inescapable, all-around niceness.

"He wasn't able to dig up one thing about me," Mahoney tells Pierce, who has reappeared in the Frasier lounge.

"I'm not sure why that is, because it's all so apparent," Pierce replies.

"You could talk about the drug thing,” offers Peri Gilpin, who plays Roz, Frasier-Crane's producer.

"I'm over that," Mahoney replies. A pause.

"God," Pierce says with a sigh. "It's been a while since we've all had sex together."

"Well, Kelsey's never available," Mahoney says. “That's why." "

Kelsey's schedule is on the door," Gilpin says.

"Kelsey's always having to have his chest shaved," Mahoney complains.

Grammer, caught later munching pickles and turkey burgers in a dressing room, speaks tenderly. "I admire him without bound," Grammer says. "And he's often said to me that if he'd had a son he would have liked it to be me. And I actually feel the same way about him."

Actor Dennis Farina feels similarly: "If there's a nicer guy around, I haven't met him yet," he says—but is not above a little sparring. Asked to recall the lowest point in Mahoney's career, the Chicago native replies, "I don't think he's reached it yet."

WITH 20 MINUTES TO GO BEFORE rehearsal, Mahoney is sitting in a chair in the makeup room, watching in the mirror as a stylist stirs up various colored mousses and tinctures and daubs them into his silver hair. In this episode of Frasier, Martin's physical therapist, Daphne (played by Jane Leeves), suggests a hair color called "cinnamon sable" to make Martin look younger. He balks, but later changes his mind and decides to dye it himself. The problem: In the store, he can't bring himself to buy the brand that Daphne advised ("There was a woman on the box!"), and so he picks an inexpensive variety: Color in a Can. Later, when Martin tries out his new look at a singles party thrown by his sons, cheap hair dye leaves permanent stains on Niles's expensive furniture.

"At first I thought it should be jet black," Mahoney tells the stylist, "but this is better; Martin isn't stupid." She finishes the job, down to the eyebrows, coloring him a seriously unattractive sort of grayish-chestnut; later, she'll give him a packet of laundry detergent to wash the gunk out. "Oh, I love it!" Mahoney says, clapping. "This is fabulous!"

Pierce walks in. "Have you seen Bebe's [Neuwirth] production of Chicago?" he asks Mahoney.

"Yes," Mahoney says. "You look like the woman who runs the jail."

"My first personal memory of John is his appearance in Moonstruck," Kelsey Grammer recalls—specifically, the moment in which a young female student throws a drink in Mahoney's face. "That was when I thought, Wow, great scene, and it remains a great scene. We worked together on Cheers—the last season of Cheers, so I guess it was '92, '93. He did a guest bit, and we got along real well then. And when the news of a father came up here, to join the cast of Frasier, of course I thought, John is perfect to play my dad. So I called him in Chicago and said, 'Read the script and tell me what you think.' He called a week or so later and said OK."

The rest, as they say—you know. Finished with makeup, Mahoney and Pierce head toward the set, and bump into Peri Gilpin and Jane Leeves, who are running their lines in a hallway.

"Oh, John!" Gilpin says.

"What happened to your hair?" Leeves moans.

"I dyed it! Like you said!" Mahoney replies, in character.

"This isn't cinnamon sable!" Leeves protests.

On the set, the cast and crew roar over Mahoney's hair ("I think I'm going to keep it!" he tells a stagehand). Grammer noodles prettily on the piano while production staffers busy themselves with cameras and props. A team of writers sit in the audience, pencils poised to revise the script. The lights go up on the party scene. "Careful with that 'Dad' stuff," Martin tells Niles. "I've got a few people here mistaking me for your brother." His cockiness will be short-lived: Just as he begins to romance an attractive woman, Martin notices to his horror that he's left an eight-inch brown stain on a white wing chair, and spends the rest of the evening sitting there hiding it. When Martin suggests that she get their drinks, then refuses to pick up an earring she's dropped, the woman leaves in a huff.

On paper, the story sounds like standard sitcom fare, but the resulting program is far smarter than the average network show. "I don't like what sitcoms do as a rule," Grammer says. "I wanted to make this one human and have a quality of playing up to the audience, always. Intelligent." The show's primary conflict seems to resonate with viewers: that of a boomer-age son taking in an aging parent. Mahoney hopes to see his 67-year-old character continue to wrestle with real-life issues. "I'd love to see Martin have some problems sexually, maybe not be able to perform," Mahoney muses. "It must be a terrible blow to a man. I'd love to explore what it's like if Martin accidentally overhears a conversation and takes it to mean that he's going to be put into a home. I'd love to see my eyesight going—with his waning faculties, I don't see why I don't wear glasses. All these little things that add up to a man feeling less than a man."

Coming from the legitimate stage, Mahoney has had to persuade the cultural elite—culture vultures, as he calls them—that TV work can have merit. "I've just been exposed to so much knee-jerk reaction as far as sitcoms go, you know?" he says. "People saying, 'Well, I hear you've got a wonderful show but I never watch sitcoms.' It's really cutting yourself off from some of the most wonderful humor. I don't think you can find better half-hours of television than you can on a couple of sitcoms, such as Frasier and Seinfeld. I mean, I just don't think you can get any better than that."

STAGING THE MAN WHO CAME TO Dinner at Steppenwolf this spring was Gary Sinise's idea, although Mahoney was happy to go along with it. His recent roles on Chicago stages have been demanding, and he could use a break. "He likes hard parts—he likes hard work," says Sheldon Patinkin, a close friend who has directed Mahoney in six Chicago productions, including last year's highly acclaimed production of Krapp's Last Tape, part of the Buckets of Beckett festival. In it, Mahoney played an old man preparing to die who talks back to tapes of himself as a young man. Steppenwolf's Death and the Maiden in 1993 was "a physically and emotionally repellent experience," Mahoney recalls, in which he was strapped to a chair and gagged for most of the play—eight shows a week, for ten weeks. "Sometimes I'd start to get a little panicky," he recalls, "where I couldn't really breathe, and my mouth would be so dry because that material in it was sucking every bit of moisture out of it. I couldn't swallow. It took me quite a while to get over that.

"I was confined that way in A Prayer for My Daughter [in 1982], handcuffed to a chair for Dennis Farina to beat the shit out of me every night," Mahoney recalls. ("He had it coming to him," Farina notes.) "Orphans [in 1985], that was another one. I'm kidnapped by this crazy young kid and tied to a chair, once again. And I spend a lot of the first act bound and gagged. With tape across mouth that time. I did that one for a year

"I've been so tortured in the last few things I've done at Steppenwolf did that was just determined that I was going to do something fun."

He's found his mark. In The Man Who Came to Dinner, Mahoney plays the irascible Sheridan Whiteside, a famous New York critic and radio star who slips and injures his hip outside the home of a small-town Ohio family named Stanley. As a result, the family has to put him up—and, as a press release says, "put up with him"—over Christmas as he takes over their house and their lives to deliver his broadcast. He won't even let them use their own phone. "It's a great part for him," Patinkin says. "He has excellent comic timing and he knows how to be as cynical and bitter as that guy is."

The play is a big-budget affair, to be directed by James Burrows, a nine-time Emmy-winning TV producer and director (Frasier, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Cheers). There are elaborate sets, Mahoney says, and 27 characters—including costars Robert Breuler, Rick Snyder, and Alan Wilder from Steppenwolf, and Linda Kimbrough, Harriet Harris, Natalie West, and Jim Ortlieb.

"All I do is sit in this nice comfortable wheelchair for virtually the whole show,” Mahoney says, grinning. "Every once in a while I pop out of it, do some surreptitious exercises, and then get back in it.” One hardship: He has to wear a "fat suit,” which tends to get warm. "Size 50 waist,” Mahoney says. "And I only wear a 36!"

PERHAPS THERE SHOULD BE a heartwarming recitation of Mahoney’s rags-to-riches immigrant success story. John Mahoney was born on June 1940, in Blackpool, England, a seaside town to which his mother had been sent for safekeeping during the Nazi bombing of Manchester, where the family lived. He was the seventh of eight children; his father was a baker who loved to play the piano, his mother a housewife who was an avid reader. It was not a happy marriage. "I don't remember them ever saying a kind word to each other," he recalls. He got interested in acting when he was 11, "to distinguish myself," he says. He did Gilbert and Sullivan around England, even going so far as to run away from home to audition for a repertory company—he was accepted—but his parents talked him into finishing his education. About the same time, he visited one of his sisters, a war bride who lived with her husband on a farm in western Illinois, and had an epiphany.

"I can't describe what it was like to go from England in 1951 to the United States," Mahoney recalls. "[England] was postwar in the bleakest possible sense. It was like living a life of black and white and gray. It was like there was no sunshine. [We] would go to the Saturday matinee, and our mothers would have to a little two-ounce coupon out of our ration books that we would then take to give to the candy person to get our two ounces of candy to take into the serials and Westerns. It was just dreary beyond belief. There was never enough food. Nobody owned a car. You were lucky if you owned a bicycle. It was like some old De Sica movie. It was like Italian realism.

“And then, all of sudden from that, to go to the United States like I did, it was Ike when The Wizard of Oz changes from black and white to color. I left England and I walked into this world of Technicolor. I walked onto my sister's farm, where they had cars, where everything was bright, the sun was shining, the sky was blue. And the air was clean, and there was more food than you could ever eat. And I knew that this is where I wanted to live. I knew I wanted, more than anything else, to move to America and to be an American."

He came in 1959, signed his "Declaration of Intent" to stay, and quickly joined the army—thus speeding his citizenship prospects and securing government help for college. With the new homeland came the idea of reinventing himself: By the end of his three-year hitch, he had lost his accent. "I swore that nobody was going to know I was from England," he recalls. "I actually made up index cards. I'd say to people, 'How do you say "ba-nah-nah"?' And they'd say, 'Ba-na-na,' and I'd write it down phonetically. I was in the army with people from all over the United States, so I might learn how to say one thing New Jersey style, another thing Amarillo, Texas,

style—it was a pretty mongrel accent, but it was definitely an American accent."

Mahoney landed a bachelor's degree at Quincy College (now University) in Quincy, Illinois, working as a hospital orderly to pay the bills, then taught classes while earning his master's degree in English at Western Illinois University. Realizing quickly that teaching was not his forte, he moved to Chicago and took a job as an editor for the Journal for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals. He had a big salary and an office on Lake Shore Drive. But he wasn't happy: He spent most evenings out drinking and smoking cigarettes, returning home to drink some more and go to bed.

And then, on a visit to his family, he swung through London and caught a Tom Stoppard play called Jumpers. In Manchester, he saw Albert Finney's Uncle Vanya; the two performances rekindled his interest in acting. Back in Chicago, he was similarly inspired by a production of Arthur Miller's A View From the Bridge. In 1977, at 37, he signed up for acting classes at the St. Nicholas Theatre, which had been started by David Mamet, Steven Schachter, and W. H. Macy. He quit his $35,000-a-year editing job, sold some of his records and furniture, and moved to a cheaper apartment in Lake View. That same year, Mahoney was cast in a production of Mamet's new play The Water Engine at St. Nicholas. "I walked down Barry Street, dancing and screaming with joy,” he recalls. Times were lean at St Nicholas, though, and he got the part on the condition that he would return his Equity-scale paycheck to the company soon as he received it. "I lied," Mahoney says. "I was making $75 a week—in good weeks." He got his Equity card.

In his second play at St. Nicholas, Ashes, he appeared opposite John Malkovich, who invited Mahoney to Steppenwolf. Mahoney's career took off: Death of a Salesman, Balm in Gilead, Born Yesterday, The Song of Jacob Zulu, Death and the Maiden, Supple in Combat. His performance in the troupe's Off-Broadway production of Orphans, directed by Gary Sinise, garnered a Theatre World Award and a Drama Desk nomination, taking his career to a new level. "I'd be in my dressing room, washing blood off my face, and Paul Newman would walk in with his hand outstretched," Mahoney recalls. Soon came the film career, which begat his work on the small screen.

It's been a great ride. His best experience on film was Say Anything, with John Cusack and first-time director Cameron Crowe—a movie that suffered from its release at the pinnacle of the "teen angst" genre, into which it was unfairly bundled, but which was praised by critics from Siskel and Ebert to Pauline Kael. "I loved that character," he says of his part. He played a doting widower so close to his daughter that they talked about everything happening in their lives—except for the fact that he was swindling his nursing home patients out of their life savings. "So dense, so multilayered; he sits there in prison and cannot for the life of him figure out what he did wrong." People most often mention Moonstruck; he remembers Tin Men fondly, as well. Of stage work: "That's tougher. I'm going to have to say it was Orphans. It moved people so much; the sobbings that we would hear in the audience. New York every night was leaping to their feet with these standing ovations and these cheers. I loved being in that play as much for what it did for other people as for what it did to me. You feel so strong, so powerful."

Amid the triumphs, Steppenwolf remains what grounds him. "We've been together for so long, and we know each other so well, and we're so like family, at we feel free to say anything, even if it causes knock-down-drag-out fights. And there have been. At our company meetings every year, there are always screaming matches; there are always people taking bottles of Excedrin after they're over. But at the same time, just like a family, it’s all forgotten. At Steppenwolf I'm used to just saying, 'Jesus Christ, what were you doing?' We keep each other honest."

WHEN JOHN MAHONEY LAUGHS, he laughs big, as if he's on a stage: great, jolting, full-bodied, rocking-back-and-forth Bellow, face-splitting smiles, blazing teeth, slapping of knees.

“He refuses to appear on TV talk shows—except for the occasional Today chat with Bryant Gumbel, whom he likes. “I’m not going to be fodder David Letterman, or Jay Leno, or any of those people," he says. "I'm not going to try to be funny and sit there sweating and wondering if I'm going to have the piss taken out of me. Why put myself through all that?"

The worst rejection he can recall: "I'd wanted to do the play Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? for years. And [the character] George is 47. I'm 57 now. And we applied for the rights, and I was told by Edward Albee's [managers] that I was too old for the part and under no circumstances would I be allowed to play it."

He lives in an eight-room apartment packed with Mission furniture and a CD player in every room, on the fourth floor of a vintage building in Oak Park; in Los Angeles, he rents a unit in a high-rise. He also has a house in England, which one of his brothers looks after, and another downstate, near his sister's home.

He gives people his home phone numbers, and says he does not screen his calls. He does not cook. If he were to have anything he wanted to eat in Chicago, it would be a mushroom, anchovy, and sausage pizza. In Los Angeles: the same. "Hold the pineapple," he says with a laugh. In Chicago, he drives a Lexus ES-300; in L.A., a Ford Explorer. He quit smoking about a year and a half ago, but contemplated relapsing during his food-poisoning episode. ("Fortunately I was too sick to leave the house to buy a pack.")

"He worries about learning his lines," says director Sheldon Patinkin, "but he's really quite good at it." Mahoney plays cards with Patinkin, Laurie Metcalf, Glenne Headly, and John Malkovich—usually a game called May I?, a form of gin rummy that he has taught most of his friends. He's a cutup: He and Metcalf have often tried to trick one another into laughing onstage. During A Prayer for My Daughter, he sabotaged Dennis Farina constantly: poking dribble holes in Farina's plastic coffee cups, sticking little notes to props that read, "You'll never make it in this business," replacing stage whiskey with real Jack Daniel's. ("John said that was the best performance I ever gave," Farina recalls.) Mahoney once told the Chicago Tribune, "The difference between Dennis and myself is that I see theatre as an end unto itself, whereas Dennis sees it as a steppingstone to his real ambition: a permanent guest spot on Hollywood Squares."

He has spent every Christmas for the past 20 years at the home of Chicago theatre producers Jane and Bernie Sahlins: "It's Christmas dinner for Jews and atheists and other alienated people," says Patinkin, who also attends. "We drink, we sing Christmas carols, we put on silly hats, and we have a really nice time."

He hates being away from Chicago. "I'm homesick all the time," Mahoney says. "I have friends [in L.A.]. But the thing is, virtually all of them are married or in relationships or have their own friends, and I just don't want to be a fifth wheel, don't want to be someone they feel they have to take care of and look after and entertain and make sure I'm happy. I can't stand the thought of that."

He has talked before of settling down with someone, but now says that time has passed. "I just don't have time for it, to tell you the truth," Mahoney says. "And I'm of an age now where I think that, closing in on 60, I'm resigned to the fact that a good book and a CD and a glass of Jameson's is probably going to be my companionship for the rest of my life."

"The theatre is my brothers, my sisters, my father, my mother, my wife," Mahoney has said. "It is everything to me." And that family extends from the Third Coast to the Left one.

"We all give as good as we get," Frasier costar Jane Leeves says of the cast. "It's a great relationship. It's like a family."

Mahoney agrees. "From the start, it was perfect," he says. "And then Peri [Gilpin] came"—she's sitting next to him—"and it wasn't quite as perfect.”

Gilpin ignores him. "Everyone's just genuinely respectful of people," she says. "Shit, I forgot what I was going to say."

"She's usually not out of the home this long," Mahoney says.

ALL RIGHT, ALREADY: YOU REALly want to know about the dog? "We've got something we pinned on the bulletin board" in the lounge, Mahoney says.

"It's a letter from a guy who said, 'Three episodes without Eddie is too much. I'm not going to watch the show anymore.' What a freak. It's like working with a robot. It's not like working with anything made out of flesh and blood. I've worked with that dog for going on five years, and it still doesn't know who I am. To get it to lick me, they would have to put liver paste on my face, which they have done in the past. If I walked in the room, if he looked at me, which is all he'd do, there would be no tail wagging. It's like something out of The Twilight Zone. It doesn't hate you. It just doesn't care." There.

CHICAGO, LATE FEBRUARY. The scene: O'Rourke's Pub on Halsted Street. Mahoney walks across the street from Steppenwolf, where he was being fitted for his Sheridan Whiteside fat suit, step inside, pulls up a stool. It's a familiar stop for him and everybody in Steppenwolf, and is probably the city's most famous Irish literary/theatre pub—Mahoney is sad to hear it's for sale. The bartender calls him Mr. Mahoney and takes away adjacent barstools, so nobody who comes in can sit next to the actor—not that he would care. The barkeep also stops accepting payment.

Mahoney looks more relaxed than he did in L.A. He's over the food poisoning. He's home. On the weekend, he has done what he describes as "a very non-Martin thing": He took in The Marriage of Figaro at Lyric Opera. "It always amazes me when people in places like that recognize me," he says. "Everybody says they don watch television, or they only watch Channel 11, but somehow they know exactly what's going on with Frasier."

He talks of looking forward to The Man Who Came to Dinner, and to taking it to London—then traveling in Venice and Istanbul. He sips red wine.

His worst trait, Mahoney says, is impatience. Then he confesses that he has recently yelled at a person in a wheelchair, "I was squeezing into a parking space at a shopping center in Oak Park," he recalls, "and this couple pulled up beside me in the handicapped space—she was driving, he was in a wheelchair—and right away, instead of just asking me to move, she starts whining at me: 'Oh, how are we going to get out?' I said, 'Would you like me to move a little bit?' She kept whining: 'How are we going to get out!?' And I said, 'Why don't you just ask me to move instead of whining at me?' She said, 'I love your movies, but I hate your personality!' I said, 'I don't want people like you watching my movies!'"

Aha! That is not very nice!

"Nothing makes me more impatient than a whiner," he says. And John Mahoney smiles.