Long before the White Sox won last year’s World Series, Bernard A. Weisberger had embarked on his latest book, When Chicago Ruled Baseball: The Cubs–White Sox World Series of 1906, due out this month from William Morrow ($24.95). The 83-year-old Evanston author, who has also worked with the director Ken Burns on several documentaries (including 1994’s Baseball), rooted for the Brooklyn Dodgers as a boy, but cheered for the Sox in the 2005 Series. “Some people think their baseball loyalty travels with them the rest of their lives,” says Weisberger. “I go with the locals.”

Q: There are baseball fans in Chicago who think that God created Wrigley Field on the eighth day, and that baseball came to an end when old Comiskey Park was torn down. Yet those ballparks don’t figure in your story.

A: Absolutely-neither one of them. The Cubs played in West Side Park, which stood right where the present University of Illinois Medical Center at Chicago is. The Sox were playing in South Side Park, which was at 39th and Princeton. The whole South Side-North Side rivalry did not exist. Both parks were south of the Chicago River.

Q: How big were the parks?

A: The old wooden stadiums were built to seat about 7,000 people, but they expanded the seating capacity by letting people stand in the outfield and along the foul lines. And for the Series, they put some extra seats between the foul lines and the stands. The first two games were played in terrible weather. It was freezing. There were snow flurries for the opening game-which happened to be the 35th anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire-so the weather held the crowds to about 12,000. But the last two games were played on Indian summer afternoons on the weekend, and the official reports of the crowds said there were 20,000. I don’t really know how they managed that, but I do know that for games five and six, there were huge mobs turned away, and there was actually a riot before the sixth game. People broke down the fences, and they had to call in the cops. But that’s all part of the ongoing story of modern America-the industrial expansion of the early 20th century. You have to be able to put 20,000 people in one place in the afternoon. You have to have enough toilets for them; you have to have enough water for them; you have to have enough popcorn to feed them. It’s an industrial operation. That doesn’t take anything away from it, but it’s not like going out into a cow pasture and popping the ball around.

|

Photography: Courtesy of William Morrow/Chicago History Museum

|

|

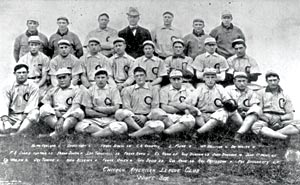

The 1906 Series winners

|

Q: Yet there was still a kind of innocence to the ’06 Series.

A: It definitely had a carnival atmosphere. People brought horns and bells and gongs. It was fun to be part of the crowd, to yell and make noise and act like a fool and do silly things. That’s something I think baseball has lost a little of; it’s so much more serious now. The funniest episode for me was in game five, which was played in the Cubs’ park. The Series was tied. The Cubs had to take two of the next three. So far they’ve lost every game in their home park-both sides had-so they decided to try and change their luck. The first thing they do is wear their road uniforms. The second thing they do is get a couple of bear cubs from the Chicago zoo and drag these poor critters around the bases.

Q: A lot of that holiday atmosphere came through in the newspaper coverage.

A: The Series itself almost became itself a national holiday for a week. And every day in the papers, it was a new sensation. You never know how many people actually followed the games, but I assume that most middle-class Chicagoans couldn’t wait to open the newspaper and follow the game. And back then, Chicago had nine daily newspapers in English alone.

Q: The style of writing was considerably different than it is today.

A: Yes, it was. It’s ragtime America. Everything is short, punchy, jazzy [snaps his fingers]. So it’s very vivid and lively, because what the writer is trying to do is [create] the pictures going on in your head. And of course, they have to do the play by play. The way most people found out what happened on the field was to open the newspaper and read. And because writing about 154 baseball games every season could get pretty boring, they had to look around for different ways to say the same thing. So that’s why they’d say, Chance slashed a double. Or, Steinfeldt poked a single into left field. All these baseball clichés that we now think are so hoary were invented by these writers.

Q: Fans who couldn’t get into the games also had the option of following the Series at a couple of remote locations.

A: As part of a circulation promotion, the Tribune had rented both the Auditorium Theater and the First Regiment Armory [at 16th Street and Michigan Avenue]. Thirty-three years before the first televised game, you could sit and “watch” the game indoors. They had a big board, and they moved the players around this diamond from base to base. There were big crowds, and it was very exciting. There was one scene described in the papers where a guy comes out and he says, “And Rohe [pause] has just [pause] HIT A TRIPLE!” And everybody screams and yells.

Q: Two characters dominate the early chapters of your book: Charles Comiskey and A. G. Spalding, a onetime player, manager, and part owner of the team that would become the Cubs.

A: Spalding’s is a fascinating cultural story. He helps to make modern baseball. He came from Byron, a small town in Illinois, and played for a Rockford team called the Forest Citys. He represents the old stock, rural America. He makes a great reputation on the field as a pitcher, and then is lured to Chicago by the businessman William Hulbert. Hulbert dies fairly soon, and Spalding succeeds him as National League president and then starts his sporting goods business.

Q: And somehow gets the job of making major-league baseballs.

A: Yes, by a strange coincidence, the official ball of the National League turns out to be the Spalding baseball. And Spalding is the one behind creating a national commission to explore the origins of baseball, which came up with the myth that it was invented in Cooperstown. Cooperstown is a very nice place, but baseball was a game that evolved from rounders and other bat and ball games. But Spalding gets this commission to declare that the game was officially invented in America.

|

|

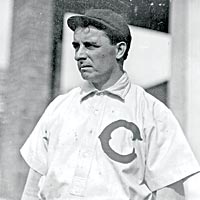

Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown

|

|

|

Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers

|

|

|

Jolly Nick Altrock, known as the Cincinnati “Dutchman”

|

Q: Spalding comes across as something of a union buster.

A: Busting the union and ending competition was Spalding’s game, and the game of a lot of others. He’s up to his neck in that. One of the things the owners were doing early on-it’s so contemporary-was screaming that player salaries were too big and that it was ruining them. Of course, meantime they’re trying to outbid each other for the good players. As early as the 1880s, they put in a reserve clause: we will reserve a certain number of players each year, and nobody can try to buy them. And the players hate it, understandably. In 1890, they actually form a Players’ League, and Spalding does everything humanly possible to bust it. And this is the era of Theodore Roosevelt and trust busting, but they don’t bust the baseball trust. It’s the national pastime.

Q: That’s the great paradox you point out: here is this supposed epitome of democracy, when in fact it’s a monopoly.

A: Owned and run by the owners, who kept competitors out and paid the players what they damn pleased. But the game is lovely if you’re a fan. You can’t spoil the game-though they’re coming close. But it’s always been a business from the late 1890s on.

Q: This is where Charles Comiskey comes in, who is a much more sympathetic character in your book that the person we associate with the Black Sox of 1919. He had been a player and a manager before becoming the owner of the White Sox, and you suggest that he helped to found the American League because he thought baseball had become too much of a business.

A: Because of the Black Sox scandal and the awareness now that Comiskey really did squeeze his players-he was a tight man with a buck-people tend to see him as one of the barons of baseball with an eye on the cash register and nothing else. But in the 1906 Series, he was not happy with doubling the prices [for a ticket]. Comiskey didn’t like it, but the National Commission shoved it down his throat. Comiskey was the son of an Irish immigrant (who became a Chicago alderman), and he was for making baseball more accessible to ordinary people, particularly the newcomers, who like to go to a ball game on Sundays, because they work the other six days of the week. And they like to have a swig now and then and have a party. But they still had a lot of Victorianism in the United States, and Sunday ball was prohibited in most places. So the Series is really a match-up between old and new: Irish immigrant America-urbanites-versus this businessman [Spalding].

Q: Comiskey, the supposed tightwad, generously rewards his players after the Series.

A: Yes, he gives them an extra $15,000 to split up. On the other hand, the hero of the Series is an unknown sub named George Rohe [pronounced “ROE-ee]. After the Series, Comiskey says, Boy, Rohe, we’ll never trade you-and he trades him the next year. But if I had to deal with either person, I would prefer to deal with Charlie than with Spalding.

Q: Let’s talk about the team’s managers, who were both players as well.

A: Fielder Jones, the White Sox manager-and his name really was Fielder-tended to be the quiet type. He was definitely the boss, but he didn’t say much. He rarely showed emotion-though in the first game of the Series, the last out was a fly ball [to Jones in center field for a Sox victory], and he did a little jig as it came down. Frank Chance, who managed the Cubs, was probably a better player-a Hall of Fame first baseman. He was a friendly dictator who ran his club with an iron hand. He made it plain that they were there to work hard. He was asked once what was the secret of his success, and he said, “I can lick any man on the club.” Chance was well liked, and he had a great career as a manager. His Cubs were one of the great teams of the 20th century. In 1906, they won 116 games in a 154-game season-and there were two games they didn’t even play. They went on a run where they won the pennant four years out of five, and the world championship two times out of four. And Chance was the manager that whole time. So there was plenty of glory for the Cubs-except that they lost the 1906 Series.

Q: The Cubs really came into their own in 1906.

A: That’s right. The big rivalry for the Cubs had been the New York Giants, who were the kings of baseball. In 1906, the Cubs had an early season series with the Giants in Chicago, and the Giants took I think three out of four. But then the Cubs went to New York in June, and they shellacked the Giants. And so one of the nicknames that the press used for the Cubs was “the Giant-Killers.” In fact, the name “Cubs” had no official standing.

Q: How did they come to be called the Cubs?

A: The Chicago National League team in 1876 was known as the Chicago White Stockings. And it was as the White Stockings that they were a dominant team through the 1870s and ’80s. And then in the 1890s, they fell on hard times. Pop Anson [more commonly known as “Cap”], who had been their longtime manager, left, so they called them the Orphans for a while. They got worse and worse, and then they started to bring in some young talent, and so some people called them the Colts and then the Cubs.

Q: Where did the Sox get their name?

A: Comiskey had built up this team in St. Paul, and then he and Ban Johnson created the American League. They wanted to establish an AL team in Chicago, but the National League didn’t like that idea. They finally were persuaded, but these were the rules: [Chicago’s American League team] couldn’t use the name Chicago, and it couldn’t come north of 35th Street. So they just took the old name of White Stockings and shortened it to White Sox. In 1906, Hugh Fullerton, a writer for the Tribune, dubbed them “the hitless wonders” [because of their meager run production].

Q: Going into the 1906 Series, there was little doubt that the Giant-Killers would trounce the hitless wonders.

A: That’s right.But the thing is, in the Series itself, three of the first four games were very tight. Game four was a two-hit shutout [a 1-0 victory by the Cubs behind the pitching of Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, who had already lost game one and would go on to the Hall of Fame]. But in the last two games [with the Series tied at two games apiece], the Sox just rained base hits. In game five, the Sox jumped off to a quick lead, scoring seven runs by the sixth inning. And in game six, they just murdered poor old Three Finger.

Q: Did Chance made a mistake going back to Brown after only one day’s rest?

A: I think so. It’s so easy to second guess, but Brown was rocked. That game was over in inning two. Chance had several pitchers on the bench, including two good pitchers he never even used. I don’t know what his strategy was.

Q: Tell me a little about Mordecai Brown.

A: Three Finger is the case of a guy who had a misfortune turn into gold. He actually had all the fingers on his hand, but he had caught his right hand in a feed cutter in a farming accident as a kid. He lost the first third of his index finger, and later broke two other fingers in a fall. But he had this stump, this knob, that when he gripped the ball, it put a spin on the ball. Ty Cobb said it was the hardest pitch he ever faced. He couldn’t tell which way it was going to break until it was over the plate. The Series saw a couple of sensational pitching duels between Brown and Nick Altrock, who loved to clown around. He was so good at it that, later on, when he retired from active playing, he made it his profession. He and Al Schacht [known as the Clown Prince of Baseball] would go around and do funny acts. So he’s remembered as Nick Altrock the clown. Everybody forgets he was a great pitcher. So what gives you your fame isn’t necessarily what you’re best at.

Q: The star pitcher for the Sox in the ’06 Series was Ed Walsh, one of my favorite players from that era. His lifetime earned run average-1.82-remains the best in the major leagues even after all these years.

A: Ed Walsh was an ex–coal miner. Comiskey said he was the greatest, and you look at his record, I think it’s hard to argue. Of course, he threw a spitball back when they still allowed it. In some ways it seems the game has changed radically in a hundred years, but the basic rules that had evolved by ’06-if you and I were transported to that ballgame, we would recognize it. The rules are basically still the same, except that the spitball is still legal, and they tried to get away on the cheap and use just one ball during a game. Occasionally a ball would get into the crowd, and the crowd was supposed to return it, but they wouldn’t. But basically you were playing with a ball that by the seventh or eighth inning was not probably dented and didn’t travel very fast [when hit]-which is one of the reasons that the pitchers could pitch longer.

Q: The ball was probably the biggest difference: the so-called dead ball.

A: That’s right: this was the dead-ball era. The dimensions of the ball were the same, but the center was rubber instead of cork, which does make a huge difference. The Cubs in ’06 hit 20 home runs, second in the National League to the Brooklyn Dodgers [who had 25].

Q: How did the dead ball affect the Cubs’ famous infield, which was celebrated for turning the double play? Tinkers to Evers to Chance-though they hadn’t become a poem yet:

A: No, the poem wasn’t written until 1910 by F.P.A., a New York writer [whose full name was Franklin Pierce Adams]. And actually they didn’t make all that many double plays, because double plays were harder to make back then because the deader balls took a long time to get out to the fielder. In fact, I’m impressed with the number they did make [the Cubs made 100 in 1906, third in the National League.] But once they were immortalized in verse, that was it. They all did go into the Hall of Fame-and deserved it. But everybody forgets there was a fourth guy in that infield, a guy named Harry Steinfeldt. He was just out of luck. He wasn’t in the poem.

Q: I always thought Johnny Evers pronounced his name “EH-vers,” but you write that it was “EE-vers.”

A: I’m fairly confident I read that in a couple of places, though I can’t remember where. Finding out how names are pronounced before tape recordings is a challenge, so you have to go by what you read.

Q: One of the more frightening moments of the Series involved Ed Hahn, the right fielder for the Sox.

A: In game three, Jack Pfeister, a lefty for the Cubs, pops Hahn in the nose with a fastball and breaks his nose. They’re a block from Cook County Hospital, so Hahn gets up and walks over there. He comes back the next day, his nose taped up, an air hose hanging out of one nostril.

Q: It seems to have a beneficial effect on his batting average.

A: Yes, it went right up. I can imagine the other players in the clubhouse saying, “Hey, how can I get the pitcher to throw a ball in my face?”

Q: Your last chapter, “After the Lights Go Down,” chronicles the players’ post-baseball lives. Some of them didn’t fare too well. Three went insane, two of them from the aftereffects of syphilis.

A: One of the questions I get asked occasionally is if they had groupies then. I don’t know about that, but the players were not choirboys, and I’m sure some of them went to cathouses and slept around.

Q: It’s an old story: you have your moment in the sun and then . . . .

A: Yes, it’s very hard to give that up. I can’t imagine what it’s like to have the pinnacle of your life occur when you’re 25 years old. Some of them did come to a very sad end.

Q: You have a quote from the Bible-Ecclesiastes.

A: Yeah, we all wind up in the same place. “The race is not to the swift . . . ”

Q: “Nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favor to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.”

A: They sure do.

Q: That’s not a reference to Frank Chance, is it?

A: That never occurred to me. That’s a wonderful thought.

Q: It would be a good title for a biography.

A: Time and Chance.