Screenwriter James C. Strouse wanted to cut through the noise surrounding the war in Iraq and write a movie about its human cost. The Goshen, Indiana, native set his script, Grace Is Gone, in the heartland and told a story he thought would resonate with both liberals and conservatives. John Cusack loved the script and signed on to produce it.

Grace got off to a great start. At the 2007 Sundance Film Festival, crowds gave both the audience award and outstanding screenplay honors to the movie, which stars Cusack as a Midwestern father struggling to tell his two young daughters that their mother—a soldier—has been killed in Iraq. After Sundance, the Weinstein Company bought it for about $4 million.

But when Grace Is Gone came out late last year, excited relatives called Strouse, 31, wondering what was going on. They couldn’t find the movie anywhere. Grace ended up in seven theatres at its widest release. Box-office receipts tallied a little more than $50,000—an astonishingly low figure. What happened? “My feeling from talking to friends and family was that they had enough [of the war]—they were turning it off; they were turning away,” Strouse says.

It wasn’t just audiences who turned away. Between purchase and release, the Weinstein Company seemed to lose enthusiasm for the film. They would not make anyone available to talk about Grace, but three months before it came out, audiences had responded poorly to In the Valley of Elah, an Iraq-themed movie that garnered Tommy Lee Jones an Oscar nod for best actor.

The barrage of Iraq news coverage has hurt, says Kevin Hagopian, a film historian at Pennsylvania State University. Moviegoers get constant reminders that the conflict won’t have an easy resolution. “This is not a war that’s going to end like Michael Clayton, where bad guys go down and good guys emerge whole,” he says. Historically, audiences have been more receptive to wartime films if there is a general consensus about the necessity of the conflict, such as World War II, says Rick Worland, chair of the division of cinema and television at Southern Methodist University. “People are expressing their disinterest in [Iraq] by ignoring these movies,” he says.

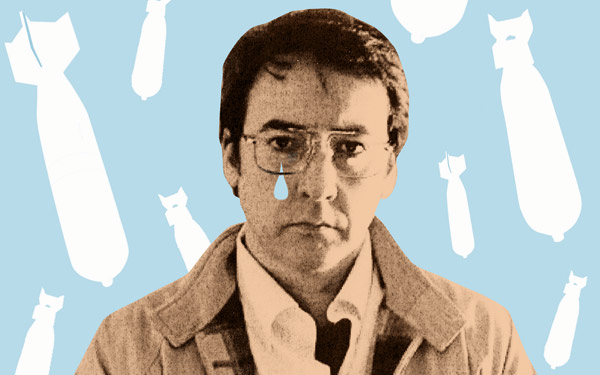

Cusack in Grace is Gone

That lack of public interest is exactly why Cusack wanted to make Grace, says Grace Loh, his producing partner at the Venice, California-based film company New Crime Productions. Strouse’s script required the actor to play “somebody opposite of himself in terms of philosophy and ideology about the war,” Loh says. (Cusack’s character supports the decision to invade Iraq.) The strength of Grace, she adds, is “that it doesn’t get on a soapbox. It’s really about family loss.”

In addition to writing the script, Strouse, who had one other movie to his name (2005’s Lonesome Jim), earned his first directorial credit with Grace Is Gone, which was shot largely in Chicago. Once the filming was complete, the movie began “a really strange journey with wild ups and downs,” he says. John Cooper, director of programming for Sundance, recalls that the response there was “amazing.” But he suspected the film’s postfestival life would be hard. “Once you mention the war, people run the other way,” Cooper says. “I knew it was a huge marketing challenge.”

When it did land in theatres, critics found strength in the “small moments” between Cusack and the girls (although a few lambasted the film’s murky position on the war). But the movie came out over the holiday season alongside fantastical films such as Enchanted, and the promotion campaign was depressing. The trailer showed military personnel knocking on the door and telling Cusack’s character that his wife has died. “I get why, over the holidays, Grace Is Gone won’t be your number one choice,” Loh says. She believes that if the film had been in theatres a little longer, it might have found an audience through word of mouth.

Grace‘s flameout has not deterred Cusack from wanting to comment on issues surrounding Iraq. His company’s next project, War, Inc., is an unapologetic satire about an assassin hired by a Halliburton-type company in a fictional Middle Eastern country. As for Strouse, he’s pursuing a master’s in crea-tive writing at Columbia University in New York. Meanwhile, with the DVD release in May, he’s wishing Grace will find its audience of people willing to watch and reflect on the movie in their homes. “I hope it will find its place at some point.”

Photograph: Courtesy of Plum Pictures/New Crime Productions