|

In 1992, when the Bosnian-born writer Aleksandar Hemon got stranded in Chicago due to the siege of Sarajevo, his hometown, his life, language, culture, and personal history capsized. Eight years later, he produced The Question of Bruno, a short-story collection that earned incandescent reviews; the clamor grew louder with the crypto-novel Nowhere Man in 2002 and a MacArthur fellowship in 2005. Many of Hemon’s fixations—immigration purgatory, the slipperiness of history, how memories congeal or evaporate—ripple through his dynamic new novel, The Lazarus Project, which comes out in May. Inspired by the actual 1908 murder of a Jewish immigrant, Lazarus Averbuch, by a Chicago police chief, the narrative interweaves past and present, eastern Europe and the Midwest, and a mission of discovery for two fictional characters, Brik and Rora, former prewar Sarajevo playmates. Hemon spoke with Victoria Lautman from his home in Chicago.

|

Q: Didn’t you once say you could never write a novel? Seems you discovered a way!

A: I could never start out to write a novel. I start out to write a book and then see what happens. But this one was harder than the first two books because those I wrote in smaller, discrete units, so to speak. I would write parts and add them and that would be the book. Whereas with this, the discrete unit was the book, and I couldn’t just put parts together. I couldn’t see all of it when I was inside of it, writing it. Only when it all added up could I recognize the structure was a novel.

Q: You first encountered Russian immigrant Lazarus Averbuch in An Accidental Anarchist [1997] by Walter Roth and Joe Kraus. Were you immediately ensnared by the story?

A: A friend gave me that book sometime around 2000 or 2001, and the things that really clinched it for me were two photos of the dead Lazarus being held up by the police captain. In one, the captain must have moved, so his face is blurred, while Lazarus’s is clear, since he was dead. It was shocking that they even photographed dead people this way, but also, there’s this reversal: The face of the living person has no identity, whereas Lazarus’s does.

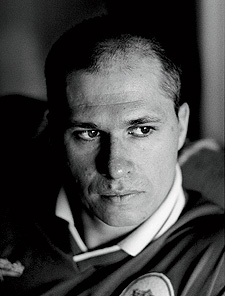

Q: So off you went with your photographer pal Velibor Božovič on a journey to eastern Europe, retracing Lazarus’s life, researching the book, and taking photos. Are you concerned that readers will conflate you and Velibor with the book’s two fictional characters, Brik and Rora?

A: It’s not that I’m ashamed of being Brik, but really, I’m every character in all my books. What I object to is not that there are pieces of me in these characters but that these might be seen as autobiography. If I wanted that, then that’s what I’d write. But reading this or any other book as concealed autobiography is very reductive. I went on the trip with the intent to write the book, but I was pretending to be a character on that trip, too.

Q: We also get pretty involved with Lazarus’s sister Olga, his friend Isador, and other characters from 1908.

A: I changed a lot of things in the story. That’s the way I like to do things: read up and absorb the story and then forget all the facts.

Q: Wasn’t your own existence called into question around the time your first book was published?

A: Just some European editors thought I was made up, a compound writer. But that was good. I like to disappear behind the book, and in that case, I had succeeded in vanishing.

Photography: Velibor Božovič