In 2010, a freshman at the University of Illinois disappeared while whitewater rafting in West Virginia. Seven hours later, her body was found downriver, her leg jammed between rocks. Her parents flew in from China, questioning how this could happen to their daughter, a good swimmer. The body was shipped to Champaign, but the hospital refused to do an autopsy, so the girl’s parents contacted Phil Corboy Jr. of Corboy & Demetrio, a prominent personal injury law firm in Chicago. He called Ben Margolis, a local autopsy pathologist.

Margolis drove down to meet with the family. “It was one of the most intimate experiences I’d ever had,” he recalls. “The mother held my face and told me to take care of her beautiful daughter. I told her she could trust me.”

During the autopsy, he found a bruise under the scalp and swelling and bleeding in the brain, which proved that the girl had not drowned. She’d suffered a traumatic brain injury, probably by hitting her head on a rock, and had most likely felt nothing. “The family was happy to know that—if you could call them happy,” recalls Corboy, who credits Margolis with providing an answer sensitively and quickly. “Ben is probably the leading expert in Chicago for these kinds of things.”

Most of us don’t like to talk about “these kinds of things.” But these kinds of things are Margolis’s job, and he was born to do it. He is impartial. He is compassionate. He is board certified. And his every action is driven by twin obsessions, each thorny in its own way, one pursued with his heart and the other with his hands: He helps vulnerable families, and he seeks the truth using very, very sharp instruments.

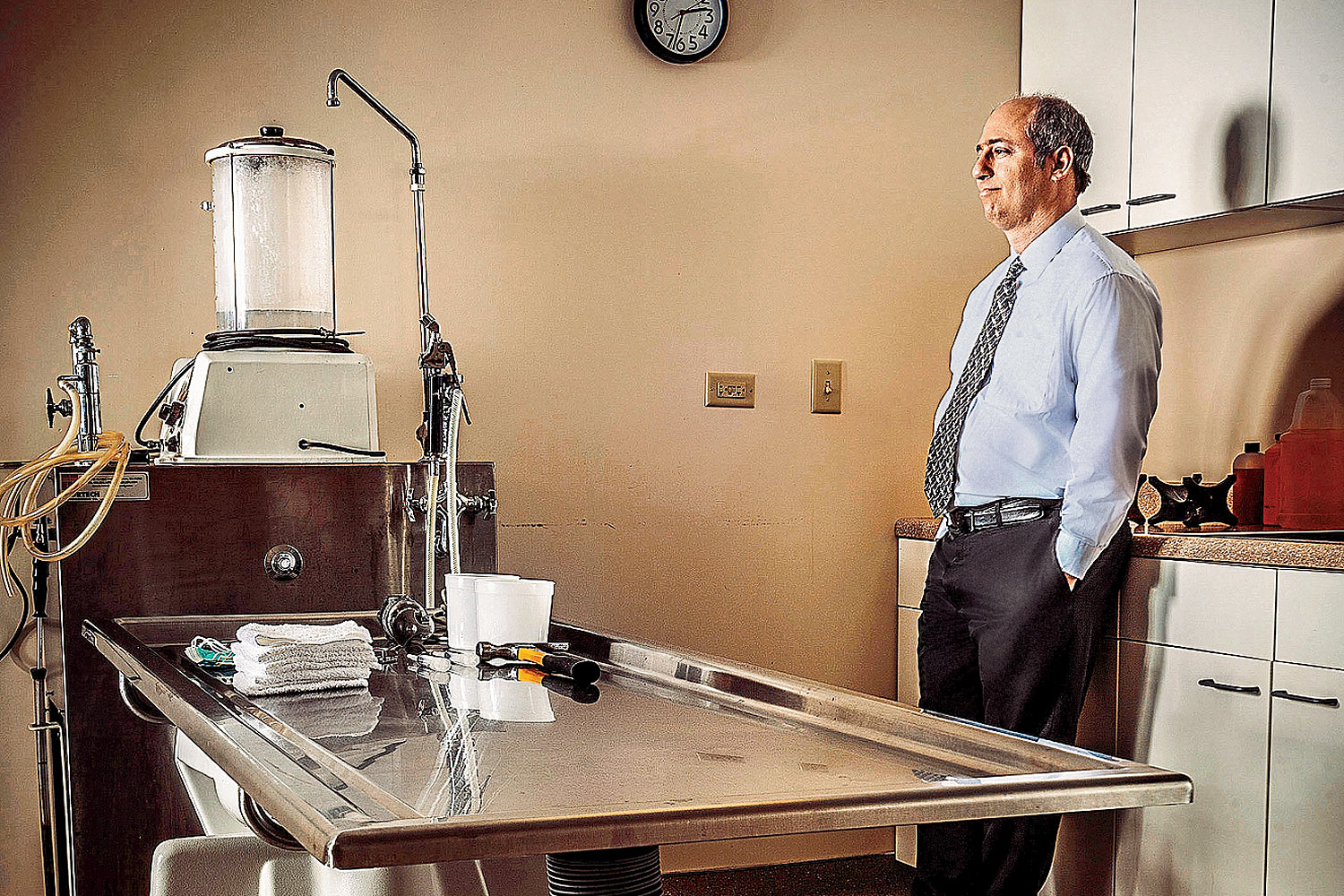

Ben Margolis looks like your average guy: pale, balding, paunchy. You’d probably gaze past him at a party. But if you ever get the chance to talk to him, do it. He won’t regale you with macabre tales; his respect for the dead makes such a thing unthinkable. But he may well be the only man in Chicago who conducts autopsies, studies improv, and plays the violin. “I’m into everything,” he says. “Having a balance is important. When I go to a concert, I’m not around death.”

Margolis, 47, has always been nimble with his fingers. He served as concertmaster of the orchestra at Harvard, where he majored in chemistry and physics; he reached the same position in the University of Chicago’s orchestra, which he joined during medical school. He’s performed everywhere from Carnegie Hall to a gazebo behind the Drake Hotel, where he once played Pachelbel’s Canon in D for someone who’d hired him to accompany a marriage proposal. (“I have played at several proposals,” he says. “I try not to cry on to my violin.”)

During his residency at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s office, Margolis saw his future. Witnessing cases involving murder victims gnawed at him, but the puzzle-solving aspects of postmortem work dovetailed perfectly with his inquisitive streak and precise hands. While working as a pathologist at Evanston Hospital, Margolis found himself to be gifted at helping grieving families. What he learned seemed obvious: People want a doctor who listens. So he launched the Autopsy Center of Chicago, unaffiliated with any hospital, and started listening.

Many families who seek his help arrive with their fists up. He disarms them not by blaming hospitals but by empathizing and by learning what they need to achieve closure. Some want to sue; others need reassurance that what happened to their family member isn’t a genetic problem they might inherit. Some simply want answers. Margolis ensures that they all leave with what they’re looking for. “Ben is a very sensitive guy,” says J. C. Hirsch, who owns Heartland Memorial Center in Tinley Park and has been a funeral director for 40 years. “Most pathologists are trained at the science end, but he’s also wonderful with people. Above all, you’re dealing with human beings in complicated situations.”

And rare situations. In the 1950s, autopsies followed roughly half of all hospital deaths; that figure has declined to under 10 percent. There are several reasons for this. In 1971, the Joint Commission, a nonprofit group that accredits American hospitals, dropped a requirement that they must perform a certain number of autopsies each year. There is also a growing perception that technology has made autopsies obsolete, says Jon Lomasney, the director of autopsy service at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. (“There’s lots of data to prove that wrong,” he adds.) Another factor, Lomasney says: physicians’ fears of uncovering errors that could result in malpractice litigation.

And then there’s the simple fact that many families don’t realize that they can ask for an autopsy if a loved one dies. Those who know may not be able to stomach one—or to afford it. (Full autopsies, for which Margolis typically charges between $1,000 and $3,000, are not covered by insurance.)

So what happens when a family hires Margolis? Here’s an example.

Not long ago, a Chicago woman died in a hospital recovery room after abdominal surgery. Her husband wanted to know whether the surgeon was to blame—for legal reasons, but also so that he could grieve unencumbered by doubt. The funeral director told him about Margolis, and the husband chose a full autopsy.

The process started with Margolis taping absorbent napkins on the floor. The woman’s naked body lay above, on a white table outfitted with a drain, a hose, and a suction. After examining her body, Margolis began removing her brain. Using a scalpel, he cut from behind one ear to the other, over the top of the head. Careful but decisive, he peeled the scalp forward until it rested inside out on the neck like a silicone mask. With a spray of dust, he used a bone saw to expose the brain. When the skullcap came loose, it made the same sucking sound as opening a jar of pickles.

After disconnecting the brain, Margolis examined and recorded every aspect of it. Then he weighed it, photographed it, and put it in a preservative-filled bucket. Next came the chest, which he opened as though unzipping a zipper, exposing a yellow layer of subcutaneous fat. Once through the rib cage, Margolis extricated organs—heart, lungs, glands—to be dissected and photographed. He did the same with the abdominal cavity, placing samples in small jars for lab analysis.

The lungs held the answer to this particular puzzle. There Margolis found pulmonary apical blebs, small bubbles common in long-term smokers that can go undetected in x-rays. They had burst while the patient was on a respirator after the operation, pushing air into the chest cavity and stopping her heart. The surgeon had not been the problem, nor had the anesthesiologist; the culprit was cigarettes. Margolis would be giving the widower a very different picture than what he had imagined.

The five-hour procedure was painstaking and messy, yet Margolis left the room cleaner than he’d found it. Rather than replace the organs in their original positions, he put them in biohazard bags that went into the chest and abdominal cavities so that they could be embalmed. Days later, the funeral was held with an open casket.

Not everyone needs an autopsy, obviously. Margolis simply wants people to know they have the option. He leads a weekly public lecture on autopsies at Bucktown’s Gorilla Tango Theatre and teaches continuing education classes to funeral directors and embalmers. In 2011, he worked on a state senate bill (now a law) that grants next of kin the right to access a deceased person’s health records.Lately, he has been developing a set of “Miranda rights” for recently bereaved families, the same desperate people who come to him looking for a fight and leave comforted by his manner.

“The truth,” says Margolis, “is you want someone who can engage with life. And my first step forward is to be me.”

You can contact Ben Margolis via Autopsy Chicago and take an Autopsy Seminar that he teaches regularly.

Comments are closed.