On a bitter cold February day—six months after her 16-year-old son, Cornell Ferguson, and his friend Johnqualas Turner were gunned down—Ashia Guy passes out fliers near the boarded-up house in Garfield Park where the boys drew their last breaths.

Though Cornell had been arrested several times for selling drugs, Guy does not believe he was in a gang or was killed in a drug-related dispute. The word around the neighborhood, she says, was that the shooter (or shooters) wanted to “make a statement” to the neighborhood—This block is mine—and fired on the boys for no better reason than that they were standing there.

After the murder, Guy, 35, then a dispatcher for a taxi company, moved with her three other children to Minneapolis to put distance between her family and the tragedy. But she didn’t give up on justice for her son. She started scraping together a reward for information that could help solve the case, eventually tapping her life savings to reach $10,000. She then took an eight-hour bus ride back to Chicago to announce it. Undaunted by the cold, she spends hours passing out fliers that read, in large capital letters:

CORNELL ASHAWN LORENZ FERGUSON

SUNRISE: JANUARY 16, 1996.

SUNSET: AUGUST 2, 2012.

MURDERED: 600 N. AVERS, CHICAGO, IL.

Listed are the $10,000 reward and her name and phone number. The names and numbers of her sister and mother are also included. As for the police? They’re not mentioned at all.

That’s no oversight. For Guy has just spent six agonizing months living through the Chicago Police Department’s abysmal record of solving murders.

The day Cornell was killed, Guy says, she beat the detectives to the crime scene, waiting for more than an hour before they arrived. For weeks afterward, she says, when she called the investigators assigned to the case for updates, they were either too busy to come to the phone or told her, “We’ll call you when we know something.” (Investigators did not return Chicago’s calls for comment.)

That’s when Guy decided to take matters into her own hands. “My son was no angel,” she says. “But I don’t want his case to slip through the cracks.”

More like the chasm. Only 132 of the 507 murder cases in the city last year were closed last year. That makes for a homicide clearance rate of 26 percent—the lowest in two decades, according to internal police records provided to Chicago. (The true picture is even worse; more on that later.) To put it another way: About three-quarters of the people who killed someone in Chicago in 2012 have gotten away with murder—so far, at least. “Those stats suggest a crisis,” says Arthur Lurigio, a criminologist at Loyola University Chicago.

It’s a crisis every bit as pressing as the city’s high homicide rate, because the former feeds the latter. If murderers aren’t apprehended, they’re free to kill again. If other bad guys get the feeling that there are few consequences for their actions, they too will be emboldened. “The word has to be out [on the street] that the cases are not being cleared,” Lurigio says.

Of course, the effects ripple out further. “It leaves a family devastated, without any sense of justice,” says Lurigio, “and it leaves an entire community with a sense of helplessness and despair.”

Given the record low clearance rate last year, more than 30 police sources, including current and former top commanders and 15 detectives, agreed to talk about the problem. These interviews—combined with the internal police data provided to Chicago—reveal a detective force that is undermanned and overextended, struggling against reluctant prosecutors and a notorious no-snitch code. Last year’s department-wide consolidation and reorganization, initiated by Superintendent Garry McCarthy, has made a bad situation even worse. As one South Side detective put it: “It’s a perfect storm of shit.”

CLEARED DOESN’T ALWAYS MEAN CUFFS

Police can count murder cases as “cleared” (solved) even when:

• The suspect has fled the country

• The suspect is in prison for another crime

• The suspect has died

• A victim refuses to press charges

• Prosecutors don’t approve charges

On February 8, Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Superintendent McCarthy, and hundreds of Chicago police officers and their families gathered in the Grand Ballroom at Navy Pier for an important ceremony: the graduation of 70 officers from detective training school. This marked the first time since 2008 that the cash-squeezed department was adding to its detective ranks, a fact that Emanuel and McCarthy proudly mentioned in speeches.

After the ceremony, McCarthy posed for pictures with the graduates and then held an impromptu news conference. The first question cut right to the chase. “Is improving the homicide clearance rate the biggest challenge for this new class?” a reporter asked. “And where is that rate at right now?”

The response was vintage McCarthy, a cop who can answer questions like the slickest politician. “The number is low,” he said calmly. “And off the top of my head I’m not positive because it fluctuates and it changes . . . . It’s not the number that we had this year; it’s the total number that we cleared. So you could potentially have 110 percent clearance. If you look at it just for 2012 or just for 2011, that’s not how the number is recorded. So I’m not positive what it is.”

That actually wasn’t doublespeak. Because it can take years to solve some murder cases, the Chicago Police Department reports the homicide clearance rate in two different ways: the annual rate (the total number of cases cleared in the same calendar year in which the crimes occurred) and the cumulative rate (which adds in cases from previous years that cleared during that year).

To add to the confusion, the terms “cleared” (or closed) and “solved,” while often used interchangeably by police, don’t mean the same thing. You probably think that to solve a murder case is to find the killer, prosecute him, convict him, and put him in prison. And in some of the “cleared” cases, that happens.

But lots of other kinds of outcomes are included in the cleared stats too. For example, detectives can clear murder cases “exceptionally”—meaning they’ve taken the investigations as far as they can. They have identified the suspects and believe they have enough evidence to charge them, but the suspected killers wind up not being arrested, charged, or prosecuted.

Cases are cleared exceptionally (“ex-cleared,” in police parlance) for a laundry list of reasons, including if a victim refuses to cooperate, if the suspect flees the country, or if prosecutors refuse to approve charges because they deem the evidence insufficient. (For more reasons, see “Cleared Doesn’t Always Mean Cuffs,” above right.)

Last year, for example, 15 of the 132 cleared murder cases—11 percent—were cleared exceptionally, according to internal police records. “The ex-cleared helps your clearance rate quite a bit,” concedes a former top police official.

All of this makes for a confusing mess of numbers. When I asked for the department’s homicide clearance rates over the past five years, a police spokesman provided the following statistics: 56 percent in 2008; 51 percent in 2009, 2010, and 2011; and 37 percent in 2012. The data also showed that 43 of 146 cases (that’s nearly 30 percent) were exceptionally cleared in 2012. But the internal clearance stats provided by a well-placed police source differ markedly: 48 percent in 2008; 44 percent in 2009; 39 percent in 2010; 34 percent in 2011; and, as previously mentioned, 26 percent last year, with 15 exceptionally cleared cases.

What gives? The “official” stats include older cases solved during each of those years, plus the cases cleared exceptionally in those years. This may leave the public with the impression that the police have solved many more murders than they actually have. The internal clearance data do not count old cases. “The department can pick and choose its numbers,” says Dan Gorman, a detective and a vice president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police. “It isn’t lying. It’s just another formula, another way of doing the math. But they are using old cases which are taking years to clear. A victim’s family is not looking for closure 20 years from now.”

Before he became Chicago’s police chief in 2003, Phil Cline was chief of detectives. During budget meetings, when he was asked to justify his payroll to city lawmakers, he would hold up a chart that compared the number of active-duty detectives with the annual murder clearance rates. “I showed them as they made more detectives, the clearance rate goes up,” recalls Cline, “and as detectives were depleted, the clearance rate goes down.”

If you apply Cline’s view to the five years during which the police department did not add to its detective ranks (2008 to 2012), it may be no coincidence that homicide clearance rates have hit rock bottom.

Cline was fortunate. He presided over the department during far better economic times than his successors. Nowadays, manpower has become the single biggest issue facing police. Cline had a force of roughly 13,500 under his command; McCarthy oversees around 12,000.

The department’s investigative side has been especially hard hit. In 2007, Cline had 1,164 detectives, each assigned to a single investigative unit: homicide, property crimes, sex crimes, special victims, and so on. McCarthy, by contrast, has 924 detectives divided among the various units. Once days off, disability, furlough, and special assignments are figured in, say union officials, the number of working detectives on any given day is probably closer to 600.

Translation: The detective division has more cases than it can handle. Teams of homicide detectives working on the South Side say they juggle as many as ten cases at a time. “You’re running from murder to murder to murder,” says one veteran homicide detective who asked not to be named. “You really want to take the time to work the case correctly, but you can’t, because as soon as you sit down to work one case, you get sent out on another.”

The 70 detectives newly minted in February will help, but their numbers don’t come close to keeping up with attrition. Not to mention the fact that the rookies have a steep learning curve after just six weeks of detective school and several months of field training, if that. “It will take at least two years for these new detectives to get good at what they do,” says Cline.

Police forensic investigators are also scarce. As of March, the department had only 14 of these highly trained specialists—CSI-style techies who notice the minute details at a crime scene and earn sergeant’s pay—down from about 40 in 2007. Increasingly, less specialized, lower-paid evidence technicians—trained to work on crimes such as robberies and thefts—are filling the gap.

Many homicide detectives complain that evidence technicians tend to overlook crucial evidence—cigarette butts, fingerprints, shards of glass—more often than do their better-trained counterparts. “Once you release that crime scene, you can’t re-create it,” says a South Side homicide detective who requested anonymity. “I have to stand over those guys [evidence technicians] to make sure they don’t miss something.”

Police officials acknowledge that, yes, money is tight and they’ve had to make tough staffing decisions. When forced to choose between money for investigations or for more beat patrols, it makes a certain kind of sense that department officials would choose the latter. Put more cops on the street to prevent killings in the first place, the thinking goes, and you’ll need fewer people to play Columbo afterward.

(Tight budgets may affect prosecutions, too. Many detectives say prosecutors, who are always mindful of expensive wrongful conviction lawsuits, are increasingly reluctant to approve charges in anything but the most open-and-shut cases. The Cook County state’s attorney’s office begs to differ. Says Fabio Valentini, chief of the Criminal Prosecutions Bureau: “The standard has been the same” since the early 1970s.)

Homicide detectives are also expensive, earning top-of-the-scale pay—about $82,000 a year for someone with five years of experience—making their numbers harder to justify to City Hall bean counters. Plus, most are drawn from the general pool of patrol officers—so when the department adds a new detective, it typically loses a patrol officer.

Just as important, detective work is less likely to prevent the kind of if-it-bleeds-it-leads media attention that can cost police brass their jobs. “The department doesn’t get judged on whether they solve the homicide,” says one former high-ranking department official. “They get judged on whether they prevent it. There was very little incentive, and there is very little incentive, to actually solve the crime.”

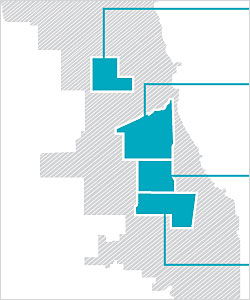

GOING THE DISTANCE: A March 2012 consolidation and reorganization moved nearly 350 detectives into bureaus further away from some of the city’s crime hot spots. Click the image to view the maps.

Garry McCarthy, a longtime New York City cop before he became the top cop in Newark, arrived in Chicago during a budget crisis that had begun years before, in the Daley era. As you may recall, a few months after taking over in July 2011, he said that Emanuel had asked him to cut $190 million from the department’s $1.3 billion annual budget. So the first two years of McCarthy’s tenure have been all about doing more with less.

The sweeping consolidation plan that he announced in March 2012 eliminated three of Chicago’s 25 police districts, closed two of its five detective headquarters (Area 4, which spanned the Near West Side and included downtown, and Area 5, which stretched from the Far Northwest Side to the Far Southwest Side), and transferred 300-plus detectives to other bureaus. The changes would save as much as $12 million, McCarthy said.

Unfortunately, the consolidation heaped still more pressure on homicide detectives, who were already struggling to keep up with bigger caseloads. Except for those detectives working in Area South (the police territory that covers roughly the southern third of the city), the realignment (and subsequent renaming) nearly doubled the area that many of them have to cover (see “Going the Distance,” right).

There are two big drawbacks here. One is that more detectives are working in neighborhoods they’re not yet familiar with. “All the expertise you once had is useless when you’re working on the other side of town,” says a detective from Area Central. “You might as well put me in a new city.”

Another big drawback to consolidation is that detectives find themselves farther away from crime scenes, sometimes by a dozen or more miles. Getting to the scene fast is crucial in any homicide investigation: Witnesses may scatter or fall victim to gang intimidation. Evidence may get trampled, tampered with, or blown away. Distance continues to be a problem later, when detectives must conduct follow-up interviews or track new witnesses in other parts of town. Says a former police official: “For every hour the detective spends in the car, that’s all time lost to the investigation.”

In what seemed to many detectives an ill-considered move, McCarthy’s consolidation removed all the homicide detectives from the West Side, where a good portion of the city’s murders occur. Under the old structure, these detectives worked in one of two places: the Harrison Area in East Garfield Park and the Grand Central Area in Belmont Cragin. Now they cover the West Side, but from as far as ten miles away, from their headquarters in North Center on the North Side and in Fuller Park on the South Side. Get this: There are now no homicide detectives stationed west of Western Avenue.

CRIME AND (LITTLE) PUNISHMENT: Chicago’s murder clearance rate in relation to the number of available detectives. Click the image to view the full set of graphs.

Last year’s clearance rate free fall appears to support the detectives’ concerns: As they moved farther away from crime hot spots, the clearance rates there fell substantially. While the rate has been slipping by three to five percentage points each year since 2007, according to the internal police records, the drop in some of the city’s deadliest neighborhoods on the West and South Sides was more dramatic. In the police district where Cornell Ferguson was killed, for example, the rate fell from 32 percent in 2011 to 18 percent last year (see “Crime and [Little] Punishment,” right).

“It takes us 45 minutes to get to a crime scene because we’re at Belmont and Western and the shooting is at Austin Avenue [on the Far West Side]—and we’re talking about sirens going, blowing red lights,” says a homicide detective assigned to the Area North bureau. “I don’t know what they were thinking when they decided to close the two areas. The city is too large.”

Not true, says Thomas Byrne, the chief of detectives, who helped devise the new district plan after McCarthy closed Areas 4 and 5. “Let’s say it takes five or ten minutes longer,” says Byrne. “Are we losing clearance rates because of that? Not in my opinion. I hate to get hung up on where they report.”

Byrne points out that the detectives are constantly out working, not tethered to their desks. “You have to get out from our building and into the neighborhoods.” What’s more, he calls last year’s clearance rate drop “an anomaly.”

The bigger problem may not be that it’s harder for detectives to get to witnesses but that it’s harder for witnesses to get to detectives. People who want to help police now have to travel miles across town—for some, that means traversing multiple gang territories—to meet with investigators. Some detectives say many witnesses simply won’t do it.

“Some witnesses have never been to the other side of the city,” says a homicide detective on the South Side. “When you’re asking someone if they will go from the West Side to Belmont and Western, they say, ‘Are you crazy?’ It might as well be the other side of the world.”

In February, when police announced charges against the two alleged gang members suspected of killing Hadiya Pendleton—a crime that made headlines nationwide because the teenager had just performed at President Obama’s inauguration—McCarthy gave Chicagoans a sense of how today’s investigations are conducted. “The community provided a lot of tips,” he said in a news conference, surrounded by the officers who worked on the case. “None of them panned out, nor did they lead to closure in this particular case.”

He continued: “However, I can’t say enough about the men and women who are standing up here today. If they look a little tired . . . that’s because they have been working 24 hours, seven days a week since this incident occurred.”

Solving murder cases is very difficult, even when the community helps the police and even when the case draws the resources that come from the political attention brought by Obama’s interest. But it can be done, and relatively quickly—Pendleton was killed on January 29, and charges were announced on February 11—provided that the time and manpower are there.

In the last few months, city officials have responded to manpower complaints with the class of new detectives, and there are whispers that another batch is coming this spring. They have also floated ideas to crack what they see as the main reason for the rising difficulty in solving murders: the no-snitch code of Chicago’s streets.

Not snitching is so deeply ingrained in high-violence neighborhoods that many witnesses, and often even the victims themselves, won’t help detectives with their investigations. McCarthy and Emanuel repeat that explanation every chance they get, including during February’s graduation ceremony. “One of the things that we talk about frequently is the difficulty we have . . . breaking the no-snitch culture and how it affects your investigations,” McCarthy told the new detectives. “Without a cooperating complainant, how can you close a case?”

But you’ve got to ask: Has the clearance rate drop, particularly last year, meant that people are suddenly cooperating significantly less? Was the code of silence really that much stronger in 2012 than in 2011, when the clearance rate was 34 percent, or, for that matter, in 2010, when it was nearly 40 percent? (Or, if you use the police department’s official numbers, 51 percent in 2011 versus 37 percent last year?)

Several current and former officers say that the no-snitch code has become the excuse du jour for city officials to spin the public and avoid sharing the blame. Others caution against placing too much blame on the communities. “To say the only thing that’s having an impact on this clearance rate is the fact that people are not coming forward is not a complete answer,” says Jody Weis, the police superintendent before McCarthy.

And yet the department has pitched a PR campaign featuring local celebrities (they won’t yet reveal who) to encourage residents to cooperate with detectives. There’s also a proposal to install street-side drop boxes, similar to office suggestion boxes, in which people with information about homicides can anonymously tell police what they know. (The idea quickly drew jeers from rank-and-file officers. “This has to be the dumbest idea the CPD has ever come up with,” one commenter wrote on the blog Second City Cop.)

Dumb idea or not, the focus on breaking the code of silence is no joke, officials say. “The bottom line: The easiest and fastest way to solve cases and hold people accountable for the crimes they committed is to get cooperation from the public, period,” says Dean Andrews, deputy chief of detectives.

Andrews and other police officials say that the homicide clearance rate has improved so far in 2013, and as of March was 66 percent. But, to be clear, half of the cases were cleared exceptionally, and that percentage only reflects the first 10 weeks of the year.

Even before Ashia Guy became a grieving mother, she and her family were familiar with what happens in most murder cases in Chicago. Last April, her half sister, Shene’e Howard, lost her 62-year-old father, Harold Howell, days after he was robbed and badly beaten inside his Old Town apartment. While the family was encouraged to see detectives at the scene of the crime, they grew less patient as the investigation dragged on.

Their frustration boiled over when detectives conceded they had made little progress. The family pressed for more information, asking about their leads and witnesses. “Don’t you have any snitches?” they asked.

One detective told the family that he was among the hundreds who had moved in the redistricting. All of his best sources were back on the South Side, not near Old Town, he explained.

The family was furious.

“Thank your mayor for that,” the detective replied.

Comments are closed.