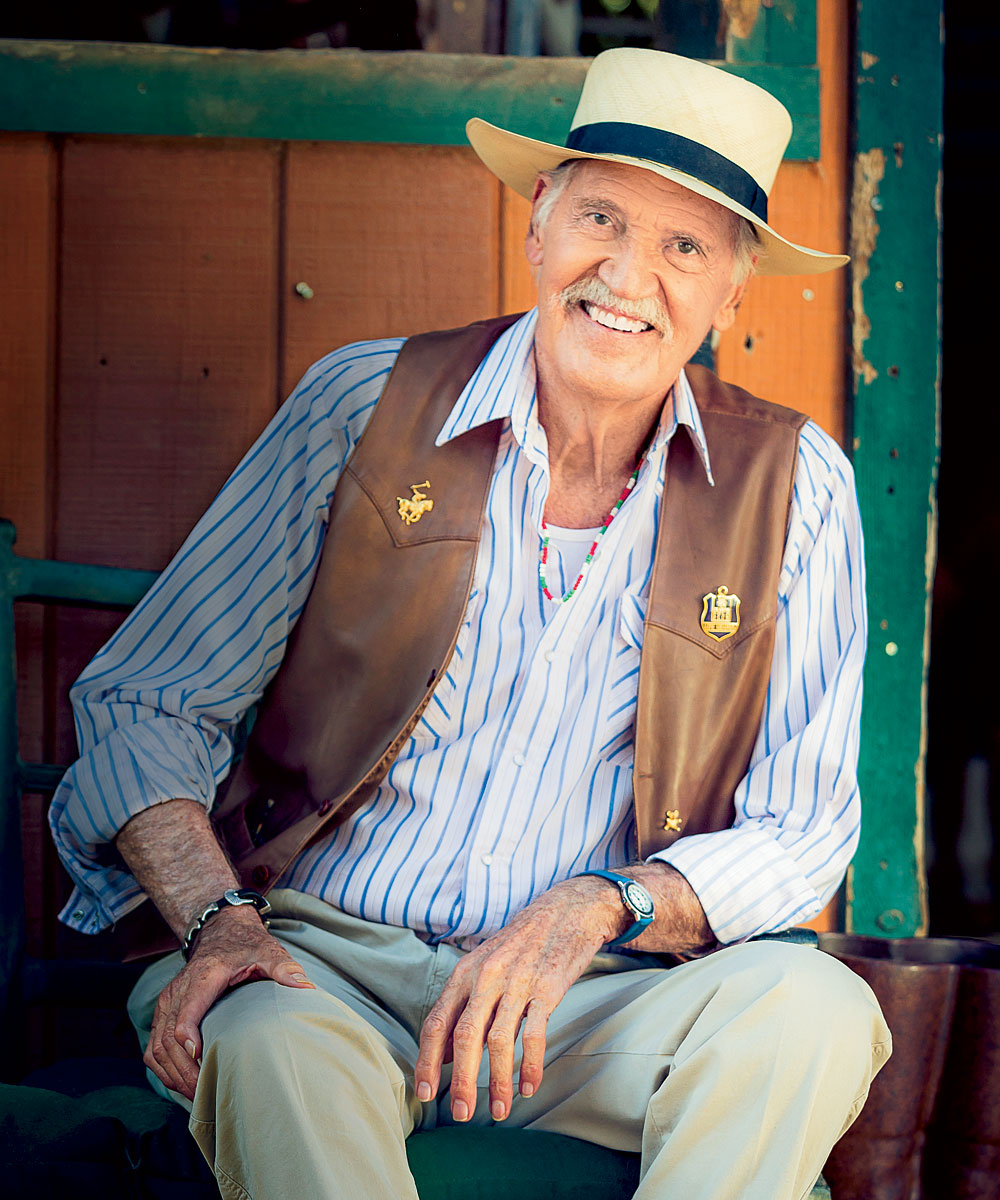

Michael Butler’s bio reads like the real-life adventures of the Most Interesting Man in the World: Polo with Prince Charles? Check. Nine-month safari in Africa? Check. Flings with Audrey Hepburn and Rock Hudson? Check and check. An heir to the Butler Paper fortune and the son of Oak Brook’s founding father, he brought counterculture to the mainstream as the original Broadway producer of Hair. This is a guy with stories—and he’s spilling in a free podcast on iTunes.

What was it like being in the middle of the ’60s scene in Chicago?

We were certainly lucky to live when we did. It’s been downhill ever since Nixon. Right after Hair opened, the authors came to me because they wanted to have a benefit for the yippies. My financial officer said, “Michael, do you realize the money for the yippies is going to the Judson Church?” It was a well-known laundromat for the radical left. I was certainly progressive, but I was not radical. I met with Abbie Hoffman and David Dellinger [of the Chicago Seven] and asked, “What are you going to do with this money?” They said, “We’re going to take on the pigs in Chicago [at the 1968 Democratic National Convention].”

What did you do?

The next day I told Mayor Daley, “You’re being set up for a very bad scene.” He couldn’t understand, and said, “Let them sleep in the park. Who cares?” The [subsequent] riots were televised. That’s what gave Nixon the presidency. Hoffman later left a note at the box office at Hair in Chicago that if we didn’t give them money, they would “get” our polo ponies. I guess he was referring to the horse scene in The Godfather.

But later you helped pay their legal fees?

I thought the way they were being treated [by federal judge Julius Hoffman] was inexcusable. [The Chicago Seven] did a lot of things wrong—I believe opposition must be kept nonviolent. They went too far in attacking the pigs. But anyone who looked at how they were treated [in custody] would not forgive it, even today.

Do you still follow Chicago politics?

I follow its politics very closely. I love Chicago. I tell everyone it’s the most beautiful city in America. If it wasn’t for the winter, I’d still live there. [Butler now lives with his son in Los Angeles.] It was beautifully run by the Daleys. I don’t like the present mayor. He’s pretty close to being a fascist with that business of closing all those schools. He doesn’t give a damn about anybody.

Your politics weren’t always so progressive. In your podcast, you talk about growing up in a very conservative family. What changed?

Every summer we had a kid from a local college who came and helped out in the garden [at the family home in Oak Brook]. He was growing marijuana, and we would smoke quite a lot. He was a pacifist, and he was being drafted. I was totally for Vietnam at that time. In long discussions with him, I began to dig into the Vietnam situation and became horrified.

Your grandfather started the Oak Brook Polo Grounds, but your dad turned it into a world-famous destination. How did that happen?

To make the village of Oak Brook [which he founded] more interesting and different he started to expand the polo operation. In the fifties, Meadowbrook [New York] was the polo capital. When it was sold, the U.S. Polo Association was desperate for headquarters. My dad offered to build out the Oak Brook grounds. At one point there were 13 polo fields. There was stabling for 400 horses. My first real job was managing the farm. People would come in from all over the world.

You didn’t start playing polo until you were in your thirties. How did you finally get into it?

One day I was walking into the barn, and my dad turned to me and said, “The Maharaja [of Jaipur] isn’t coming. Why don’t you take his ponies and start playing?” I wound up playing on my father’s team. I played with Jack Murphy and Cecil Smith, the world’s top-ranking polo player. That went on for many years while I was managing the polo club.

At one point, you considered running for the U.S. Senate in Illinois. Why didn’t you?

Hair. I learned about the play in a racket club [in New York]. I thought it was about Indians because [the poster] said “America’s Tribal Love-Rock Musical.” I went to the first preview off Broadway and discovered here was the play that really told what was going on with the war. I asked [producer] Joe Papp if I could take it to Chicago. He said, “We don’t do that.” I went back to Oak Brook, and the phone rang 10 days later. Joe said, “We’ve got very good reviews. Would you want to be involved as a producer?” I called [former governor] Otto Kerner and then Mayor Daley and said I wasn’t going to run. They thought I was nuts.

For a musical that is such a product of its time, Hair still resonates. Why do you think that is?

It’s astonishing how much people love Hair. I think the majority of people in the world want peace. And that’s what Hair’s really about.

Do you have any regrets?

One of the big regrets was losing Audrey Hepburn to Mel Ferrer [her future husband]. She was something else.