The first officer to arrive on the scene outside the Thompson Center found one of the men in a pool of blood at the bottom of the stairwell, the other lying prone on the steps nearby. The man at the bottom of the stairs, a white man, was in full police uniform beneath his overcoat. His handcuffs and radio were on the ground next to him. His gun was still holstered. He had been shot six times. His name was Paul Bauer, and he was a police commander—the highest-ranking Chicago officer to die in the line of duty in nearly 30 years.

The man on the steps, a black man, was Shomari Legghette, a four-time felon. When the police arrested him, they found a handgun and bulletproof vest under his black coat.

In all likelihood, the men had never met before the day their lives tragically collided. They were less than a decade apart in age, both were fathers, both were from the South Side—Bauer, 53, grew up in Gage Park before moving to nearby Bridgeport, and Legghette, 44, was raised in Bronzeville. They were separated by little more than the Dan Ryan. Yet they lived worlds apart.

In the aftermath, they have been portrayed in black-and-white terms: Bauer as the hero who met a tragic end, and Legghette as the career criminal who should never have been free to walk the streets in the first place. But the story of how they wound up in the stairwell that February 13 afternoon is much more complicated.

He was not born into the force, didn’t inherit the badge from a lineage of patrolmen and sergeants and lieutenants and captains. When he died in the line of duty, Paul Robert Bauer was memorialized as the best the Chicago Police Department had to offer. And though his friends and family are proud of his service, there are now moments when their thoughts drift, if only briefly, to a career path he might have taken in which the man they loved never considered it his duty to answer the radio call of a fleeing suspect.

“I used to ask Paul, ‘What if you didn’t become a policeman?’ Because he just—to me he wasn’t really the kind of guy who would become a police officer,” Erin Bauer says in the kitchen of her Bridgeport home three weeks after her husband’s death. Behind her on a shelf sits a framed photo of the couple smiling on their wedding night in 2002, 16 years ago to the day of Paul’s wake. “Not that police aren’t smart, but he was just very intelligent. He had an engineer’s mind. He could’ve easily been a lawyer. Easily.” She pauses for a moment to wipe away tears that have begun to pool in the corners of her eyes. “But he liked being a police officer,” she says finally with a sigh of resignation. “He loved it.”

Long before the CPD, there was the Catholic Church. That was the first institution Bauer came to serve. His family believed early in his life that he was destined for the priesthood. He was the youngest of four children and the only son of Paul Sr. and Annette, both of German-Irish descent, who had settled in Gage Park, a predominantly white, working-class, and Roman Catholic enclave on the Southwest Side. On Sundays, the family would walk the two blocks from their house, a modest brick cottage on the 5500 block of South Fairfield Avenue, to Mass at St. Clare of Montefalco Parish. As soon as he was old enough, Bauer began serving as an altar boy.

The church functioned as both the physical and the moral center of the community. Like his three sisters, Bauer attended grammar school at St. Clare, where he became acquainted with the works of mercy, a set of precepts that emphasize social justice and compassion for the sick, poor, and wayward. Bauer rarely, if ever, ran afoul of the nuns, who leaned on corporal punishment to enforce order in their classrooms. “Some kids were more mischievous. He wasn’t in that group,” says Steve Matteo, who was a friend of Bauer’s since first grade. “He was more sensible, smart enough not to get in trouble and get beat up by a nun.”

When it came to moral lessons, there was no shortage of instructional material for the nuns to draw from in their own backyard. Bauer’s formative years were marked by simmering racial tensions on the city’s Southwest Side. Those tensions were perhaps most acute during the summer of 1966, when Martin Luther King Jr. organized a series of marches through Gage Park and surrounding all-white neighborhoods in protest of housing practices that discriminated against blacks. King and his followers were met by counterdemonstrations, with all manner of objects and racist epithets hurled in their direction. George Lincoln Rockwell, the founder of the American Nazi Party, attempted to capitalize on the unrest, holding a rally in Gage Park that was followed by a so-called White People’s March. Paul Bauer wasn’t yet 2 years old in the summer of ’66, but the events lingered in the minds of residents long after as a dark chapter in local history.

At home, Catholic doctrine on the eternal battle between good and evil was supplemented by a steady diet of Hollywood westerns, the genre of choice of Paul Sr., a carpet installer who controlled the family’s lone television. Pauly, as the youngest Bauer was known around the neighborhood, proved a quick study. Sporting a cowboy hat and a pair of silver six-shooters holstered at his hips, he dispensed frontier justice during family role-play. “Paul was sheriff, my dad was his deputy, and my mother was his assistant,” Bauer’s eldest sister, Pam Howell, recalls with a wistful laugh. “Us girls were the bad guys. We’d be locked up.”

After St. Clare, Bauer was accepted to St. Ignatius College Prep in Little Italy, one of the most selective Catholic high schools in the city. He and longtime friend John Escalante—who much later would rise through the ranks of the Chicago Police Department to become first deputy superintendent—graduated together in the class of 1982. Bauer was generally a solid student, but he excelled at math. His proficiency led him to choose finance as a major at Northern Illinois University.

On campus in DeKalb, he landed a job with student security. He worked the night shift in the dormitories, signing residents in and patrolling the grounds. It was his first real taste of authority, and he relished it. “He always had this sense of justice and fairness,” says Keith Calloway, another member of NIU’s student security staff who went on to join the Chicago police force. “We both came into Northern looking at the business part of the world, but I think we both found a bond in doing public service.”

At the start of Bauer’s senior year, in the fall of 1985, he and Escalante took and passed the Chicago Police Department entrance exam. Bauer returned home to break the news that he had enrolled in the academy to his family, who had been under the impression he would soon be interviewing for entry-level jobs on La Salle Street. “I guess his sisters said, ‘Why are you doing that?’ ” Erin Bauer says. “And he said, ‘I just couldn’t picture myself sitting behind a desk for the rest of my life.’” Says Pam: “He was a people person, talked to everyone on the block. I don’t know how he could be a people person in finance.”

Bauer graduated from NIU in May 1986. Two months later, he was sworn in as an officer of the Chicago Police Department.

Shomari Legghette is on the phone, calling from the Jerome Combs Detention Center in Kankakee. He won’t speak much about the incident that landed him behind bars, where he’s facing 56 felony counts, the most serious of which is first-degree murder—charges to which he has pleaded not guilty. But he has other things he wants to share. The biggest is his irritation with the way he’s been portrayed in the media. “They’re trying to paint this picture of somebody that I’m really not,” he says.

Friends and family members, too, have a hard time reconciling the laid-back kid they knew from years back with the steely-eyed accused cop killer in the mug shot. “People see a monster,” says Bridgette Tucker, the first girl Legghette dated in high school and a longtime friend. “If I was on the other end and I didn’t know him, I’d probably feel that way, too. I just feel like sometimes you have to dig a little deeper and wonder, How does it happen? Because it doesn’t just happen overnight. Nobody wakes up like that.”

Legghette’s mother, Regina Legghette, was 18 when she had him in July 1973, in the waning days of the Black Power movement. Her son remembers her as a light brown, heavyset woman who wore long dreadlocks with cowrie shells. She loved books and musicals and collected Afrocentric art. Friends of hers would don dashikis and gather for jam sessions on congas. Legghette was the first of her three boys, 13 years older than the youngest. Regina gave them African names. Shomari’s is Swahili for “forceful.”

She had help in raising her boys from her mother, Gladys, a public school teacher, and father, Wilbure, a salesman and Korean War veteran remembered by family members as a broad-chested, light-skinned man who favored button-down shirts and suspenders. Legghette, who attended Fuller Elementary School, lived with his mother and other relatives in his grandparents’ house, on the 600 block of East 42nd Street.

His birth certificate lists his father’s age, 22, but not his name. When Legghette was 5, his grandfather sat him in his lap and told him, “You’re a bastard just like me.” Legghette didn’t know what that meant. “For a long time, I thought my grandfather was my pops, because I didn’t know any better,” he says. One summer, when Legghette was 8 or 9, his mother told him she had invited someone over she wanted him to meet. That was the first time he laid eyes on his father, a social worker for the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. Legghette describes his relationship with his dad, who had another family, as “distant.”

The opposite could be said of his connection with his mother. “That was my best friend,” he says. “She had me young, so we had a close relationship. And as we got older, our relationship got closer. I never hid anything from her. If I was good or bad, she knew she could take my word for it.” Regina worked as a nurse for Chicago Public Schools and trusted her oldest to help care for his siblings when she was away. Her youngest son, Khari Lark, remembers Legghette cooking them pancakes and eggs, tuna casseroles, stir-fries. He looked up to his older brother. “I was always in his room,” Khari says. “He would be listening to music, doing pushups, or making raps.”

Bronzeville, where they grew up, has a rich history. African Americans who came from the South during the Great Migration forged a vibrant community in the racially segregated neighborhood, known as the Black Metropolis. But by the ’70s, when Legghette was a child, Bronzeville’s fortunes were in decline. Residents were grappling with the loss of industrial jobs and the rising tide of gangs on the South Side. The landscape was rife with vacant lots, abandoned buildings, empty storefronts, and neglected public housing. Once Legghette stepped off his grandparents’ stoop, he says, “I was truly around nothing but gangsters, killers, and drug dealers.” Still, as a kid, he didn’t get mixed up in any of that. What he did was play basketball.

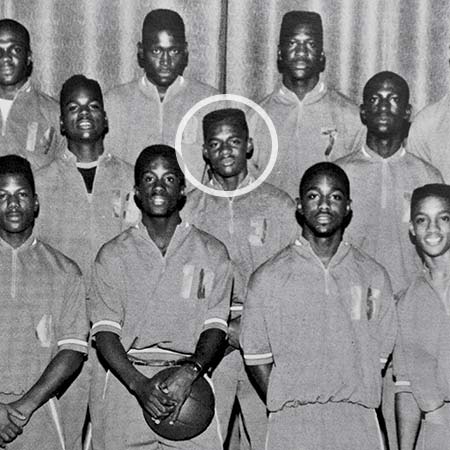

His grandparents’ house was across from Sumac Park, which was bustling in the summer. People would blast music from their cars, kids would jump rope and play on the jungle gym, and Legghette and his friends would shoot hoops. “When Shomari came to the court, you wanted to go see him,” says Marcus Perkins, who grew up in the area and had cousins who were friends with Legghette. “He handled the ball really well, and he could jump out the gym. He can still dunk a basketball at his age now.”

Six feet tall and lean, Legghette played on the varsity team at Dunbar high school and was good enough to merit a handful of mentions in the local papers. He notched 23 points and eight rebounds in a January 1991 win over Lindblom. Later that month, the Tribune reported that “Legghette clotheslined Jerard Billingsley while he attempted a layup” in a loss to city powerhouse King. In a game the next month, a blowout of Robeson, Legghette scored 31. His Dunbar coach, Fate Mickel, remembers Legghette as a good kid who never gave him any problems, but he declines to say much more: “That was 30 years ago.”

In high school, Legghette wore Girbaud jeans with creases ironed in, fresh Nikes, and crisp-collared button-down shirts. Tucker met him their freshman year, when they were 14, and liked that he was handsome, put together, and polite. They rode their bikes together around the neighborhood. They spent hours talking on the phone, cracking jokes, discussing their days, and holding forth on hip-hop. (Both were fans of A Tribe Called Quest.) Tucker wasn’t allowed over to boys’ houses, so he visited hers and watched TV while her mom cooked and kept a watchful eye. “I dated a few other guys when I was a teenager, and they would be handsy,” Tucker says. Shomari wasn’t like that. “We would sit and just talk. He never made me feel uncomfortable. I never had to tell him, ‘Stop, don’t do that.’ He was always respectful.”

Their romance lasted only a few months, but they remained close. “Our circle of friends, we were good kids,” Tucker says. “We didn’t cut class and all that. We were rule followers.”

Many of the people in that circle, she points out, are doing well now. Tucker, 44, is a social worker for Evergreen Park public schools. Another friend is a college basketball coach. Some are city workers. It was one of those, a police officer, who called Tucker in February and brought tears to her eyes with news that her old boyfriend had been arrested for murder.

While Legghette was still in high school, Paul Bauer was getting his feet wet on the police force. Around 1990, having logged a few years as a patrolman, he received his first significant assignment: to the gun task force, a tactical unit targeting people illegally possessing firearms. The transfer coincided with the start of what would go down as one of the most violent periods in Chicago’s history.

“Lots of guns, lots of shootings,” recalls Kevin Ryan, who at the time was assigned to a narcotics team. (Much later, as deputy chief of Patrol Area Central, Ryan would become Bauer’s boss during his time as 18th District commander.) “Back then we were doing 700, 800, 900 murders a year.” In the basement of the 2nd District station in the Fuller Park neighborhood on the South Side, Bauer’s and Ryan’s units split office space, a setup that enabled them to share intel. “All the gangbangers with guns also were dealing dope,” Ryan says. “So [Bauer’s unit] would give us the dope information, and we’d give them the gun information.”

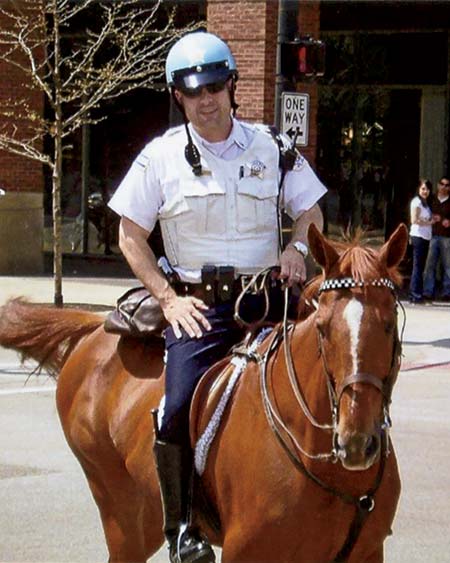

Bauer seemed to be keeping his career options open. In December 1992, he earned his master’s in public administration from the Illinois Institute of Technology. But then he began to rapidly ascend the police ranks. Over the next several years, he moved from tactical officer in the 1st District to patrolman in the mounted patrol unit to tactical sergeant in the 22nd District to sergeant in special operations to sergeant back in mounted patrol.

Bauer’s sharp mind and even-keeled temperament made him stand out as a candidate for promotion, Ryan says. “He was exceptionally smart to begin with. Excellent common sense, logical. He wasn’t overly boisterous. He was very contemplative, reserved. But people liked him, people gravitated toward him. Plus, he was very honest and dedicated. He got things done.”

It was at a 1999 benefit for the family of a slain officer that Bauer met Erin Molloy, a no-nonsense daughter of Bridgeport. She made the first move when he walked by her. “I think he was going to use the bathroom, and I said, ‘Hey, Tom Cruise.’ I’d probably drank two beers,” she says. They kept up a lively banter. Afterward the party moved to Ira’s, a now-defunct cop bar on the Near West Side. Molloy and Bauer chatted again briefly, then she turned around and he was gone.

A few months passed. Molloy still couldn’t get him out of her mind. She recalled where he’d said he worked and gave him a call. “He didn’t remember me,” she says. “He goes, ‘Yeah, maybe we can meet for coffee.’ So I’m like, ‘I’m not calling him again.’ ” Some weeks later, she found a message on her answering machine. It was from Paul.

They met up at a bar in River North. “I wasn’t sure how it was going, and I was like, ‘Do you want another? I’ll buy.’ Later, he says, ‘You passed my first test: You offered to buy.’ ” They soon began dating, and Bauer eventually proposed to her on the steps of Nativity of Our Lord in Bridgeport, the church she had attended since she was a child. They were married in February 2002.

After graduating from Dunbar in 1991, while Bridgette Tucker and other friends in their circle went off to Northern Illinois and other schools, Shomari Legghette headed south, to Mary Holmes College in West Point, Mississippi. He joined the basketball team as a walk-on, with hopes of playing his way into a scholarship. But he ran into problems: lack of financial support from back home, the culture shock of a small town, sinking grades that landed him on academic probation. Eventually, he was kicked off the team and left school. “It was bad decision-making,” he admits.

By the time he moved back to Chicago in 1993, his mother had married and was living in Rogers Park. Legghette bounced around between her apartment and his grandparents’ house on 42nd. He spent a semester at Kennedy-King College in Englewood. He worked part-time for about a year stocking trucks for UPS for minimum wage, making a little more than $100 a week before taxes. And he became a father. Initially, he saw his daughter regularly, but he lost contact after her mother moved to another neighborhood when she was about 3, according to court documents.

Life was a struggle for Legghette. He couldn’t afford to rent his own apartment, buy nice clothes, or take his girlfriend out to eat. “You’re young and you want things,” he says. “It’s tough.”

He was sending out his résumé for better-paying jobs but was running out of patience. So he turned to selling drugs. “By me growing up in Bronzeville, I knew the streets were always there for me,” he says.

In November 1996, Legghette was standing near his dad’s house in Bronzeville when an officer “observed him soliciting funds on the public way,” according to police reports. The officer searched Legghette and found seven plastic packets containing what Legghette admitted was cocaine, according to the arrest report. He took a deal from prosecutors and pleaded guilty to possession of a controlled substance—a felony—and got a year of probation.

After that wake-up call, Legghette stayed out of trouble, he says. For about six months, he worked part-time at Senior Sweeps as a janitor and senior aide, earning $5 an hour. Then came a day in January 1998 that “changed my life,” he says.

That day, Legghette, 24 at the time, got into a car with John Fowler, a man nicknamed Trouble. According to Legghette, the two weren’t particularly close, but Legghette knew members of Fowler’s family and asked for a ride from Bronzeville to his mother’s apartment up north. Fowler took him on a detour, Legghette says, to suburban Forest Park: “He said, ‘I have to take care of some business.’ ”

There, prosecutors say, Fowler and Legghette approached a man named Mike Bullington in his driveway as he was about to get into a car with his wife. Fowler, wielding a chrome pistol, demanded money. Legghette says he was surprised to see Fowler holding a gun, though authorities maintain that he had been aware of the plan. Legghette told prosecutors that Fowler then pointed the pistol at him and ordered him to take the woman’s money as Fowler robbed Bullington. According to authorities, Legghette had his hand inside his jacket, acting as if he had a gun.

Fowler and Legghette then led the police on a 30-minute car chase that exceeded 100 miles per hour on the expressway. Their car crashed into several tollbooths, but they kept going until a roadblock forced them to stop. They abandoned the car and fled in different directions. Legghette was soon apprehended; Fowler got away and wasn’t arrested until more than eight months later.

Fowler and Legghette were each charged with two felony counts of armed robbery. Fowler took a plea deal and got an eight-year sentence. But Legghette refused such a deal, maintaining his innocence. His case went to trial, and in April 1999 he was found guilty on both counts and that June was sentenced to 16 years in prison.

The outcome devastated Legghette, who remains bitter about it to this day. “Why would I take a plea deal if I knew I didn’t do anything? I was railroaded.”

His mother was heartbroken over his conviction, but she never wavered in her support. On July 19, 2003, more than four years into her son’s prison term and less than two weeks before his 30th birthday, Regina decided to make the five-hour trip downstate to visit him at Centralia Correctional Center. Khari, her youngest son, remembers a sense of unease that day: “The cat was meowing like he didn’t want her to leave.” She squeezed into a 15-passenger van of a shuttle service specializing in transporting people to Illinois prisons. Her husband, Lee Davis, would later tell the Tribune that he had a bad feeling about the trip because the van was so full of people: “They were crowding; you had parents holding kids in their hands. It just didn’t seem right to me. But she wanted to see our son, and I couldn’t say no.”

Outside Kankakee, on Interstate 57, the driver of the van lost control. It rolled over multiple times and hit a highway sign. Two boys—a 3-year-old and an 8-month-old—died in the crash. Regina was paralyzed from the neck down. The accident made news, which is how Khari found out: “I came in from a hot summer’s day playing in Rogers Park, and my mom was on the TV screen.”

Legghette didn’t know she was coming to visit that day. “She wanted to see me so bad because my birthday was coming up, and I guess she was surprising me,” he says. But when a guard ordered him to go see the prison chaplain, he knew something was wrong. “That’s when I got the news. That numbs you. That’s your mother.”

Two years later, in July 2005, Legghette was released on parole, having served seven and a half years of his sentence, including time served while awaiting trial. That August, he and Khari took their mother, now confined to a wheelchair, to watch Blue Planet at the Imax theater on Navy Pier.

About a week later, Legghette got a call from Little Company of Mary Hospital in Evergreen Park. His mother had been taken to the emergency room. He doesn’t remember what for. She appeared fine when he visited her.

The next day he got a call that she had slipped into a coma. He went to see her again and found her unresponsive. The following day, she was pronounced dead. The cause was listed as a pulmonary embolism, a blockage in the arteries of the lungs often caused by blood clots. The condition, known as deep-vein thrombosis, is a common complication of spinal cord injuries.

“Everything happened so fast,” Legghette says. “Of course I felt responsible for [her death], in a way.” But he is deeply resentful about the circumstances. “I lost my mom because she came to visit when she shouldn’t have been coming to visit me in the penitentiary, because I shouldn’t have been in the penitentiary in the first place.”

Two years before Legghette’s mother died, Paul Bauer was facing what his widow describes as the “low point” of his police career. It stemmed from a fatal incident during the evening rush hour of January 2, 2003. A sergeant in the mounted patrol unit at the time, Bauer had the sleepy assignment that day of overseeing four officers on horseback stationed in the Gold Coast. He worked his shift in a police cruiser and was driving south on State Street back to his office at the police stables at the South Shore Cultural Center when an employee of the restaurant Redfish flagged him down to report that two people had just stolen a patron’s wallet and fled in a vehicle. Bauer told the employee to ride with him in order to point out the suspects’ car. (This was in defiance of a police rule, Bauer later admitted in a deposition.) Bauer made a U-turn and headed north on State, quickly catching up to the suspects’ Dodge Intrepid. He turned on his lights and siren, but to no avail.

At Wells and Wacker, something extraordinary happened: The driver of the Dodge stopped at a red light, opened the door, and placed the purloined wallet on the road. As the car made a right turn onto Wacker, Bauer stopped to grab the wallet and radioed to dispatch that he’d recovered it. The dispatcher relayed that a sergeant assigned to supervise the progress of the pursuit had ordered Bauer to terminate the chase. But Bauer ignored the order, on the grounds that he was of the same rank. He continued into the Loop as the Dodge sped through red lights and intersections heavy with traffic and pedestrians.

At Randolph and Wacker, a westbound cab collided with the Dodge. Bauer testified that he had not witnessed the crash; had he seen it, he would’ve been forced to end the chase, per police order. The Dodge proceeded south on Wacker, then west on Madison. After blowing through one red light, it ran another at Madison and Desplaines.

That’s when an SUV rammed into the Dodge, causing it to then hit 25-year-old software developer Qing Chang as she stood waiting to cross the street on her way home from work. She and her unborn child were killed. Chang’s husband, Yong Huang, wasn’t aware that his wife had been pregnant until the autopsy results were released.

Huang brought a wrongful-death lawsuit against the city. Conducting the 2004 deposition of Bauer, attorney Michael Baird grew argumentative as the veteran police sergeant repeatedly claimed he did not see a risk in pursuing a vehicle that was running red lights through downtown Chicago during rush hour.

Baird: You were prepared to put people at risk until the person being chased proved to you that it was now too dangerous.

Bauer: No, I wasn’t putting anyone at risk.

Baird: Well, you know someone was killed in this incident, don’t you?

Bauer: Yes.

Baird: You would consider that to be a relatively major potential problem in a vehicle pursuit, correct?

Bauer: It’s a horrendous thing.

Baird: A fatality.

Bauer: [Nodding head].

Baird: It’s about as bad as it can get, correct?

Bauer: Yes.

In the deposition, Bauer referred on occasion to the suspects’ vehicle as “the bad guys’ car.” He recounted that he kept his distance at moments during the chase because “I didn’t want the bad guys to know that I was following them.” Bauer would testify during the 2005 civil trial that he didn’t stop the chase after retrieving the wallet because he was intent on making an arrest: “My job or any policeman’s job is to catch a criminal, and by them just throwing the wallet, it doesn’t make everything even. They committed a crime.”

Even as Bauer defended his actions in court, he suffered behind closed doors. “It was very painful for him,” Erin says, “and he prayed for that woman and her family.”

“Of course he blamed himself for it,” says Bauer’s old NIU classmate Keith Calloway, who’s now deputy chief of the Chicago Police Department’s Education and Training Division. “He was just trying to do the right thing. That was really hard on him.”

Ultimately, a jury awarded Huang $17.5 million. The case helped prompt the police department to add additional rules to its general order regarding vehicle pursuits.

However, the tragic affair didn’t seem to slow the trajectory of Bauer’s career. In the time between the chase and the resultant trial, he was promoted to lieutenant of the 12th District on the Near West Side.

By the summer of 2006, Shomari Legghette had been a free man for a year. But he was still reeling from his mother’s death and the consequences of his conviction. Now in his early 30s, he was routinely passed over for jobs because of his criminal record, he says. Work, when he found it, was mostly limited to minimum-wage labor or temp jobs.

He had an even more pressing need to make money: He was a father now for the second time. The mother was someone he had dated in high school and kept in touch with through the years, even while in prison. In June 2006, they had a daughter. It was a “conscious decision,” he says: “She wasn’t a mishap or anything like that. She was planned to be. That was a blessing.”

As a child, Marcus Perkins had known Legghette mostly through Perkins’s cousins (one of whom was killed in Bronzeville at 23). But after Legghette got out of prison, the two men formed a strong friendship. Many of their conversations centered on Legghette’s daughter and his frustration with not being able to provide for her. He was trying hard not to resort to crime, Perkins says.

Perkins thought he could help. His parents ran the Inner City Youth and Adult Foundation out of the Swift Mansion in Bronzeville. Among other work, the nonprofit conducts outreach programs that connect ex-convicts with housing and employment resources. Perkins’s parents would ask their son to put together a list of people who were looking for construction work, and though Legghette’s name was always at the top, things never panned out. “I don’t know what it was about him, but [contractors] never hired him,” Perkins says.

At one point, Perkins was hopeful that a building project near the 700 block of West Huron Street would take Legghette on. Perkins was a laborer at the site and says his boss told him to invite Legghette down so he could meet him. “At least four or five times that I can think of, Shomari came to the job with his boots, his hardhat, his belt, and his hammer. He sat outside all day long, hoping to get pulled on,” Perkins says. “But he was always given the runaround. They turned Shomari away, this grown man who has bills to pay and a kid to feed.”

Eventually, Legghette’s desperation became too much, and a series of arrests and jail stints followed. In November 2007, at the age of 34, he was pulled over for driving the wrong way down a one-way street. Police say they found a handgun and a bulletproof vest—both illegal for a felon to possess—and a plastic bag containing heroin in his van. Legghette took a deal, pleading guilty to a felony charge of possession of a firearm with a defaced serial number. He was given a prison sentence of three years. He first got out in October 2009 but twice violated parole for failing drug tests and was sent back to prison both times. He was released for good in August 2010.

The next few years brought more charges related to drug possession and battery, but Legghette managed to avoid jail time. That is until January 2015, when he pleaded guilty to a felony charge of possession of a controlled substance and was sentenced to two years in prison. He was released on parole in August 2015.

Grace Ann, the only child of Erin and Paul Bauer, was born the day after Christmas in 2004. At 40, Paul was a dad. “He would always say, ‘I never particularly wanted kids, or knew if I wanted kids, but once I had her, how wonderful it was,’ ” Erin says. Bauer threw himself wholly into parenting, especially as Grace entered school. He doted on his dark-haired little girl, helped her with math homework, taught her to play chess, coached her in softball, coorganized a father-daughter dance, and sat on the Local School Council and her school’s finance committee.

Bauer was elevated to commanding officer of the mounted patrol unit in 2008, and that would be the closest he would come to living out his childhood dream of being a Wild West sheriff. Ryan recalls a scary episode several years back, when he was commander of the 1st District. A fight between rival gangs had erupted in Grant Park, with Ryan and his officers caught in the middle. Suddenly, as if materializing out of thin air, Bauer’s cavalry rode to the rescue. “I remember him coming charging in, leading the horses,” Ryan says. “He basically saved our asses.”

As devoted as he was to the mounted unit and its horses (in keeping with tradition, he’d named his Doffyn, for Daniel Doffyn, a Chicago officer who was fatally shot, after only eight months on the job, in 1995), Bauer seemed unwilling or unable to allow himself to stay in one place too long. He was moved up to captain in 2015, serving as the 18th District’s executive officer. In July 2016, three decades after he joined the department, he was promoted to commander of the 18th District.

“He really took charge there. He understood the work in 18,” says Marc Buslik, who, as commander of the neighboring 19th District, communicated frequently with Bauer. “There are things that make the 18th District tricky to run. It’s not a real homogenous district.” Stretching north from the Chicago River to Fullerton Avenue and west from Lake Michigan to Ashland Avenue, it is home to some of the city’s most bustling commercial strips but also dense residential areas, high-end condominiums but also public housing, businesspeople but also club-hopping night owls, and it sees plenty of large public demonstrations. “There’s no monolithic way to police a place like that. It’s variable, it’s dynamic, and you have to be able to respond so quickly to changing conditions,” Buslik says. “Paul just seemed such a natural.”

It certainly didn’t hurt that the new commander, with his slicked-back hair, Officer Friendly smile, and piercing blue eyes, looked straight out of a Dick Wolf police procedural. Bauer prioritized community outreach, attending public meetings and hosting a monthly Coffee with the Commander get-together at Eva’s Cafe in Old Town.

He also began to give public voice to department-wide anger about changes to the criminal justice system that he and other officers believed had made it more difficult to keep repeat offenders locked up. Specifically, he zeroed in on reforms ordered by Chief Judge Timothy Evans that went into effect last September requiring Cook County judges to set affordable bonds for defendants charged with a nonviolent offense.

“Even when we catch somebody, there’s still a long way to go to get them off the street,” the website Loop North News quoted Bauer as saying at the annual meeting of the River North Residents Association in November 2017. “We’re not talking about the guy that stole a loaf of bread from the store to feed his family. We’re talking about career robbers, burglars, drug dealers. These are all crimes against the community. They need to be off the street.” Bauer couldn’t understand why Cook County sheriff Tom Dart would be pleased about reducing the number of pretrial detainees in the county jail. “Maybe I’m jaded,” Bauer said, according to Loop North News. “I don’t think that’s anything to be proud of.”

Erin Bauer says her husband’s exasperation stemmed from something elemental: “Paul didn’t like the idea of people getting away with things.”

The morning of Monday, February 12, Marcus Perkins dropped his kids off at school in his white Chevy truck, visited one of his properties in Bronzveille, and, around 9 o’clock, picked Shomari Legghette up from a friend’s house where he was staying nearby. The two then drove to Perkins’s house in the south suburbs, where they would often hang out.

“When he came with me, he always felt a relief, he could let his guard down a little bit,” Perkins says. “His spirits were good. It was just the life he was living that made him have to have that bulletproof vest on, to have that gun on him. It stressed him out. And me, for one, it freaked me out, so I would make him leave that stuff at home. I’d say, ‘Hey, man, we’re going somewhere where no one knows you.’ And he would always tell me, ‘Marcus, you’re the only person I would come out the house like this for.’ He took everything off when he came to my house.”

That morning, the two friends ate waffles, watched ESPN, and caught up. “He was telling me how him and the mother of his kid had just had a falling-out,” Perkins says. Perkins had a piece of advice for his friend: If he wanted to stay in his child’s life, “say sorry and promise to do better.”

About 2 p.m., Perkins drove Legghette back to the city and invited him to go to Carbondale with him the next day to work on some properties Perkins owned. Legghette declined. “He told me he couldn’t go because he had a parent-teacher conference Wednesday,” Perkins says. “Tuesday an officer gets killed, and Shomari’s name is all on the news.”

On the day Paul Bauer was killed, his schedule was full of meetings. In the late morning, he arrived at the Robert J. Quinn Fire Academy in the South Loop for active-shooter training for police and fire department brass. While such sessions can include drills, this particular one centered on incident command: how the two departments would work together to respond to the type of devastating massacre that coincidentally would happen the very next day in Parkland, Florida.

Once the session ended, Bauer drove north into the Loop. He had a meeting at City Hall with 2nd Ward alderman Brian Hopkins, 42nd Ward alderman Brendan Reilly, and others to discuss how Chicago and Northwestern University police might address crime on the school’s Streeterville campus. Parked near the corner of Clark and Lake around 2 p.m., Bauer happened to catch a call on the radio. He heard a description of the fleeing suspect: long black coat with a fur collar. A moment later, he spotted someone who fit the description—a man later identified as Shomari Legghette.

Though Bauer’s rank didn’t require that he do so, he joined the pursuit, radioing in a location: “State of Illinois Building toward City Hall.” He attempted to apprehend the man at the top of a stairwell on the southeast side of the Thompson Center, near the corner of Clark and Randolph. The two men struggled. Legghette fell down the stairs.

What happened next is unclear. Bauer either fell or continued pursuing Legghette to the landing of the stairwell. That is where prosecutors say Legghette drew a 9-millimeter Glock with an extended clip and shot Bauer six times. The commander suffered bullet wounds to the head, neck, torso, back, and wrist. He was rushed from the scene to Northwestern Memorial Hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

On a Saturday morning in mid-March, Shomari Legghette sits facing a video screen at the Jerome Combs Detention Center in Kankakee, about 60 miles south of Chicago. An austere metal staircase ascends diagonally through the bare-walled, fluorescent-lit space behind him. Other men in bright orange jumpsuits, like the one Legghette is wearing, drift in and out of the frame. Mustache and beard neatly trimmed, Legghette waits with a stoic expression for a reporter’s face to pop up on the screen. When it does and the “visit” begins—one of 16 phone or video conversations, lasting almost four hours total, he has with Chicago—Legghette looks directly into the camera. He has a lot to say.

It’s unusual, and maybe a bit unwise, he admits, to speak on the record with a reporter during a pending criminal case. But he wants people to see him for more than what the headlines scream. He doesn’t expect a magazine story to change his circumstances, and he prefers to save his defense for the judge.

Officers who were patrolling Lower Wacker Drive that day because of a recent shooting and drug trafficking in the area say that Legghette took off running when they approached him. Legghette is mum about what he was doing in the Loop but says he wasn’t looking for trouble. Heroin, cocaine, and marijuana were later found on him, according to police reports.

Legghette won’t say if he wore body armor out of fear of anyone in particular, only that, given his lifestyle, taking precautions makes sense in the neighborhoods he frequented: “If you swim, you should have you some scuba gear. If you play football, you got on a helmet and pads. If you’re in the streets, you gotta secure yourself. The police have on body armor. Why is it that the police can wear body armor and the citizens can’t? Why is that unlawful when it’s people out here getting murdered? I live in constant fear, because I’ve seen a lot. I can’t count on my hands how many friends I know who got murdered, man. I’ve been shot at by a lot of people.” Why did he plead not guilty to the murder charge? “Because I’m not guilty,” he says. “Would Trayvon Martin have been guilty with George Zimmerman if it had went the other way?”

If he’s convicted of murder, he will likely spend the rest of his life in prison. He worries what that would mean for his relationship with his younger daughter, now 11. “It’s a hard pill to swallow because my main concern is her.”

He’s been a good father, he points out. He helped teach his daughter her ABCs, how to count money, how to ride a bike. He also taught her to play basketball and says she has “a lot of potential,” both as a student and a hooper. “I’m trying to help her get to the next level of being a grownup and understanding what this world is about so that she stays focused and knows what she’s supposed to do as far as school, as far as staying dedicated to what she believes in and what she want to be, and don’t let anybody curb that.”

If it comes to it, prison won’t stop him from encouraging her, even if he isn’t there to watch her next steps. “If I gotta talk to her and guide her from here, that’s what it’s going to have to be.”

Yet, sitting in jail, awaiting his next hearing, Legghette can’t help thinking about what might have been. For him, it all goes back to 1998, when he got into a car with Trouble. “Without that, my life would have never taken the route it did.”

He talks for a while longer, until the timer at the bottom right corner of the screen ticks down to zero and the window goes black.

The day after Paul Bauer’s death, plastic blue ribbons began appearing on signposts and light poles throughout Bridgeport. They were tied in great numbers to the iron fence that partially surrounds Nativity of Our Lord, the Bauer family’s church, where Paul’s funeral Mass would soon draw thousands of mourners. At the February 17 service, his daughter, Grace, now 13, stood at the lectern and, with a degree of composure that belied her age, delivered a Bible reading, as she often did when accompanying her dad to the Mass at Mercy Home for Boys and Girls on the Near West Side where police chaplains pray twice a month for officers killed in the line of duty. Paul’s sister Pam read aloud a passage from the Second Epistle to Timothy: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith. Now there is in store for me the crown of righteousness.”

A few blocks from the church, a store was selling T-shirts emblazoned with Bauer’s police portrait. The same photo appeared on memorial posters that were hung up across the neighborhood, on the windows and doors of businesses and homes.

And so one afternoon in early March, it is Paul’s smiling face that greets a visitor to the Bauer residence on 37th Street. The weather is clear and sunny, but the blinds of the house are drawn.

Earlier in the day, Erin had been online reading about a phenomenon known as “widow’s brain,” which is commonly described as a kind of grief-induced amnesia. She admits struggling to recall specific memories about Paul. “The days are going by so fast,” she says. “I’m in a fog.”

What she easily calls to mind are the many long-term plans she and Paul had made. He aimed to retire when he turned 55, in November 2019. And once Grace had gone away to college, they would’ve spent part of the year in Florida—or perhaps out west. “We had gone to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and absolutely loved it. He loved it,” she says. “Whenever we’d hear bad news or sad news in the city, he’d say, ‘Idaho!’ ”

The everyday reminders of Paul’s absence continue to accumulate: the strange stillness of his basement workshop, the painful finality of speaking about him in the past tense. “I finally got him watching Game of Thrones,” she says, laughing through tears. “I’m sad that he’s not going to be with me to watch the final season.”

But to Erin, the cruelest irony is that Paul was always the one who got the family through life’s most difficult times. “I’m a worrier and he wasn’t,” she says. “And he knew how to handle any situation. If I had a situation with somebody or something, he just had the best advice. Always. All the time.”

A week after Paul was killed, Erin composed an open letter—“a letter I never thought I’d have to write”—in which she thanked Chicago “for the outpouring of love and support at this horrendous time in our lives.” “One man almost stole my faith in humanity,” she wrote, “but the city of Chicago and the rest of the nation restored it.”

She continues to find comfort in advice Paul would frequently offer her, advice that resonates these days with deeper significance: “Don’t go after the problem. Let the problem come to you.” His words now grant her some relief from the sadness and the anger and the despair. For a moment, at least, it’s as if he’s there beside her once again.

Comments are closed.