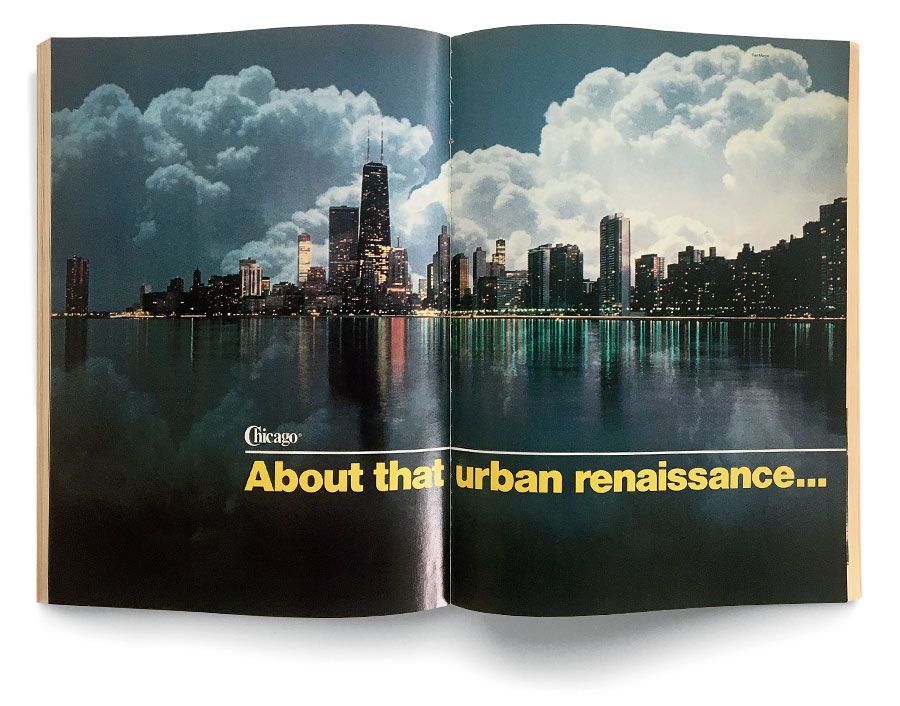

Forty years ago, when Chicago was transitioning from blue collar to white collar, the media trumpeted the influx of young urban professionals who had come to fill the jobs. In his May 1980 Chicago story “About That Urban Renaissance … ,” Dan Rottenberg was the first to describe this demographic as “yuppies” in print. He tried to temper claims that the shift was saving Chicago from the ruin of other manufacturing cities like Detroit. (We also checked in with Rottenberg five years ago, on the 35th anniversary of this story.)

Between 1970 and 1975 alone, the number of white households in Chicago with children dropped from 488,000 to 447,000, a loss of 41,000 households and the biggest drop in any category of the Census Bureau’s housing survey. Nevertheless, the arrival of the Yuppies was the first spontaneous evidence of new urban life in 30 years, and so the “urban renaissance” was hastily proclaimed.

But the word “renaissance” usually implies a cultural rebirth pervading all of society. The renaissance in Chicago has, in fact, been limited to a few oases. Of the 30,000 new housing units constructed in Chicago between 1970 and 1975, nearly half are concentrated in just 28 of the city’s 840 census tracts; as you might have guessed, all 28 of those tracts are on or near the lakefront.

Rottenberg thought the way to a more sustainable regeneration, besides revising a restrictive building code that favored teardowns over renovations, would be to encourage yuppies to stop concentrating on the north lakefront and move into more affordable neighborhoods. People have taken his advice too readily, perhaps, re-creating the displacement struggles and soaring rents of Lincoln Park in Bucktown, Logan Square, and Pilsen. Some Chicagoans, it seems, are still waiting for their urban renaissance.

Read Rottenberg's full story below.

About That Urban Renaissance…

… there’ll be a slight delay.

Yuppies flood the lakefront, but it takes families to save a city.

When Laney Sirott moved from Chicago's South Shore to Highland Park in 1949, suburbia was the new obsession of upwardly mobile families. She was 14 at the time and, like others of her generation, she grew up with the notion that the city is a nice place to work, but you wouldn't want to live there, especially with a family.

By 1977, Laney had a marriage behind her and a boutique of her own in Chicago—the Eclectic Eye on Oak Street—but she was still living in a large house in Highland Park, partly out of habit and partly in deference to her three teenage children and her dog. The children, during the day, were stranded in Highland Park without their mother to chauffeur them around. Still, there seemed to be no alternative. Old myths die hard.

About that time Laney met and married Herb Sirott, a Loop attorney who had spent six years living out his variation of the suburban myth in Arlington Heights. Herb and Laney's marriage offered a chance to re-evaluate their assumptions. Both of them were spending their days in the city while their offspring were in the suburbs. They were becoming more familiar with the Edens Expressway than with their children. Thanks to oil cartels, commuting by car was no longer a mere trifle. The suburbs were beautiful, but the city was more exciting.

Logic dictated a move back to the city. The living habits of most suburbanites, of course, are dictated less by logic than by other factors, such as fear. Still, in the summer of 1978 the Sirotts moved themselves, Laney's three children, and the dog into a three-bedroom condominium at the north end of State Parkway.

Their greatest fear—bad city schools—turned out to be groundless. Laney's eldest daughter, Beth, was just graduating from the University of Wisconsin. Her 16-year-old, Amy, was moved from Highland Park High School into Chicago's advanced-track Lane High School on the North Side; because she came from Highland Park, with its presumably superior school system, she was admitted without having to take Lane's customary entrance exam. Although Amy complained about leaving Highland Park, she now says she loves Lane. Laney's son, David, 14, is now an eighth grader at the private Anshe Emet Day School on the North Side.

"It's very easy living here," Laney Sirott says now. "Here, the children don't need me as much. They have some apprehension of the dangers of the city, but the truth is that they're out there riding around on buses. They learned the bus system in a week or less, they travel all around with ease, and they seem to enjoy it."

At this point it might be appropriate to suggest that Laney Sirott, who once represented the vanguard of the move to the suburbs, is now leading a reverse wave of chic upper-middle-class families back to the cities. And that is exactly what is being suggested by many social observers. From coast to coast, wishful thinkers are greeting the return of ex-urbanites like Herb and Laney Sirott as proof of the "regentrification" of central cities or, better still, as the beginning of a new American "urban renaissance."

"What is beginning to happen now in America is a flowback of people from suburbs to inner cities," exulted Eric Sevareid on the CBS Evening News in 1977. "They rehabilitate old homes because it's cheaper than building new homes. Older people flow back because their children, products of the postwar baby boom, are now grown and departed. Young couples do it because they can't afford the suburbs and because they prefer the lifestyle of the cities."

Last year The New York Times Magazine took note of the process of regentrification, whereby "affluent young professional people—the 20th century gentry—have been moving into previously deteriorating city centers and driving out the working class and the poor" in many of America's older cities. Chicago was not one of the cities mentioned by the Times, but last October the Chicago Tribune chimed in with its own assessment of the rebirth of several lakefront and near-Loop neighborhoods. "There is little doubt," glowed the Tribune, "that an urban renaissance is occurring in Chicago."

Well, something is occurring in Chicago, or at least in the fashionable lakefront neighborhoods that so many observers (including, God knows, this magazine) often seem to confuse with the city as a whole. Real-estate prices have skyrocketed. Lofts and townhouses are being rehabilitated. Some 20,000 new dwelling units have been built within two miles of the Loop over the past ten years to accommodate the rising tide of "Yuppies"—young urban professionals rebelling against the stodgy suburban lifestyles of their parents. The Yuppies seek neither comfort nor security, but stimulation, and they can find that only in the densest sections of the city.

According to the wishful-thinking scenario, as the demand for young-professional housing drives lakefront prices beyond affordable levels, the "Yuppies" will push northward, westward, and southward, regentrifying previously decaying neighborhoods in a continuing outward process until most of the city looks like an urban version of Winnetka, populated by the sort of affluent, astute, civic-minded, taxpaying people that any city needs to survive and flourish—the sort that the city has been losing to the suburbs since the late 1940s.

There are just a few things wrong with this scenario. First, anywhere from 80 to 90 percent of the Yuppies now flocking to the central lakefront are not suburbanites at all, but city people moving from other sections within the municipal limits. It may be encouraging that they are choosing to move downtown instead of out to crabgrass country, as their parents would have done, but the city is in fact luring very few suburbanites back from their ranch houses.

Second, there are concrete limits to the expansion of Chicago's elite neighborhoods. It's one thing to rehabilitate an old house in Lakeview or turn an abandoned industrial loft south of the Loop into an apartment; it's another experience altogether to move into a place across the street from the Robert Taylor Homes or Cabrini-Green, the two massive public-housing developments whose intimidating presence effectively boxes most of Chicago's gentry into a relatively small geographic area, thus forcing prices within that area higher and higher.

Finally, virtually all of the new housing in the Loop and lakefront consists of one- and two-bedroom apartments and small townhouses geared to singles or childless couples. According to the 1975 housing survey of the U.S. Census Bureau, 53 percent of the housing units on or near the lakefront are occupied by singles, and 87 percent are occupied by households without children. Even a glowing demographic study by the City Club of Chicago—which predicted that young white middle-class people would "engulf" several non-white, non-middle-class neighborhoods—was forced to concede, "It is also now clear that these young whites who chose to live in this part of Chicago are for the most part single or married without children."

Although Herb and Laney Sirott are the sort of attractive and visible couple whom the media love to discover, the fact is that I had a hell of a time discovering the Sirotts. Of the dozens of Yuppies, urban pioneers, and former suburbanites I talked to while preparing this article, only a handful had school-age children. And of that handful, only the Sirotts had taken a child out of a suburban school and placed her in a Chicago public school. And even the Sirotts were willing to entrust only one of their two school-age children to the uncertain mercies of the Chicago public-school system.

Certainly it's good news that somebody desirable is moving back into the heart of Chicago. But whatever cultural rebirth is taking place in the city today is being accomplished without many families or children. In an age when the family unit is presumably out of fashion, perhaps Chicago has no choice but to appeal to singles and the childless to restore the city's vitality. But in most ethical and civilized societies, the family remains the most appropriate vehicle for transmitting values from one generation to the next. Judging from the roller-coaster nature of Chicago development in recent years, it's precisely the sort of vehicle the city badly needs right now.

Every city has a different personality, and most are guided in their local planning by some generally shared beliefs about the meaning and purpose of life. These beliefs are rarely discussed or debated; they are simply assumed. In Boston, for example, with its centuries-old Puritan influence, the assumption is that as long as the city is producing a cadre of outstanding leaders, everything else will fall into place; thus the city's strong emphasis on education. In Philadelphia, with its strong Quaker influence, the assumption is that if people are left to their own devices, most problems will work themselves out, which explains the age-old ineffectualness of Philadelphia's city government.

Chicago, on the other hand, has been guided by the belief that dynamic and sweeping action is always preferable to inaction—or, as the city's original urban strategist, Daniel Burnham, put it, "Make no little plans." Chicago may have many virtues, but patience is not among them. "In Philadelphia, they boarded up the old homes for ten years and then rehabilitated them," observes Chicago's premier gadfly architect, Harry Weese, referring to Philadelphia's showcase Society Hill section. "Here, we just knock 'em all down."

The second basic premise behind Chicago planning is the trickle-down theory—that as long as the center of the city is healthy, its health will radiate to the outlying neighborhoods and the suburbs. And "health," in Chicago, is usually measured in terms of property values; new structures are justified in terms of the business and taxes they will generate—little else.

Certainly that was the guiding theory behind development in the Daley era, when the Loop became the world's tallest collection of office buildings. Between 1955 and 1975 the city sprouted more than two dozen buildings 40 stories or taller, including three of the five tallest buildings in the world. At the same time, the city installed an unrivaled expressway network whose primary function was to make commuting to the Loop as fast and pleasant as possible for executives living in the suburbs.

In some respects this was farsighted planning. America's economic future appears to lie not in manufacturing, but in the service functions performed so well by all those glass-encased towers in the Loop. By attracting corporate headquarters and more than 50 foreign banks (compared to none 30 years ago) into the bold new Loop, Chicago has assured its survival at a time when low-skilled industrial jobs are gradually vanishing to the South and the Far East. When the last industrial job has departed these shores for Hong Kong, Seoul, or Taipei, Chicago may well have the last laugh on all the snow-belt cities that hesitated to bulldoze with Chicago's reckless abandon.

The trouble with making big plans, though, is that things have a way of changing before the plans can be put into effect. Under the Daley vision, the Loop was set up as a business center whose primary function was to serve suburbanites; the commerce generated by this arrangement would somehow trickle down to the rest of the city.

But it hasn't and it isn't because several other things happened in the meantime. The suburbs lost their glitter, and Gold Coast-style city living became the new opiate of the urbane upper classes. Cars, too, lost their luster. In Loop offices that had once been staffed by a few highly paid professionals supervising armies of low-paid clerks and secretaries, the clerks and secretaries were replaced by machines, so that today the professionals outnumber the support staff in many downtown businesses. The Loop work force, in other words, became much more affluent, and much more capable of affording the high rents adjacent to the Loop.

Perhaps most important was the emergence in the late 1960s of new patterns of divorce, childlessness, and working wives—patterns that demographers say are probably here to stay, at least for a generation or so. The prime requisite for suburban living is a full-time stay-at-home wife. But who needs a house in the suburbs when there are no children? When husband and wife are both working? When husband and wife are divorced?

Thus it was that Yuppies began regentrifying poverty areas along the lakefront, such as Lincoln Park, Old Town, New Town, Lakeview, and Uptown. As population expert Pierre de Vise has noted, these singles are able to establish beachheads in "the buffer zones separating the Gold Coast from the slum" because the singles are less concerned with poor schools and street crime than middle-class families. The families, which had been fleeing to the suburbs since about 1950, continued to flee—would you send your child to a Chicago public school? Between 1970 and 1975 alone, the number of white households in Chicago with children dropped from 488,000 to 447,000, a loss of 41,000 households and the biggest drop in any category of the Census Bureau's housing survey. Nevertheless, the arrival of the Yuppies was the first spontaneous evidence of new urban life in 30 years, and so the "urban renaissance" was hastily proclaimed.

But the word "renaissance" usually implies a cultural rebirth pervading all of society. The renaissance in Chicago has, in fact, been limited to a few oases. Of the 30,000 new housing units constructed in Chicago between 1970 and 1975, nearly half are concentrated in just 28 of the city's 840 census tracts; as you might have guessed, all 28 of those tracts are on or near the lakefront.

Contrary to local conventional wisdom, what's good for the Loop and the lakefront hasn't necessarily been good for Chicago. Some white professionals may be moving back into the center of the city, but twice as many of them continue to flow out to the suburbs. Population expert Philip M. Hauser estimates Chicago's population this year at 2,918,000, down from 3,325,263 in 1970. Over those ten years, Hauser says, the city has suffered a net loss of 606,300 white residents and the white proportion of the city has dropped from 60 percent to 47 percent.

Despite the soaring prices of housing along the lake, a 1975 census report showed that the median home value and median rent (in constant dollars) had actually declined in Chicago as a whole over the previous five years. For all the demand for housing downtown, the number of housing vacancies in Chicago as a whole increased slightly, and demolitions increased by 20,000 per year.

Despite the frantic real-estate activity along the lakefront today, a 1975 study by Pierre de Vise turned up entire neighborhoods—mostly in black ghettos or blue-collar areas—where there hadn't been a single conventional house sale all year; virtually all of the conventional mortgage sales, de Vise found, were restricted to the North and Northwest sides, the Far Southwest Side, and lakefront houses and condominiums.

"Poor people have a lot more options in Chicago than middle-class people," de Vise notes. "Three fifths of the city, maybe four fifths, is considered unlivable by middle-class people, white or black. As the remaining homes in prime areas become scarcer, prices go up. Meanwhile, housing prices in the rest of the city are plummeting."

Despite the boom in Michigan Avenue boutiques, a 1979 Census Bureau study reported that the number of retail establishments citywide had fallen by nearly 4,000 from the 23,827 stores counted by the bureau in 1972, a drop of nearly 17 percent.

And despite the increase in Loop office space, the city as a whole lost 200,000 jobs between 1970 and 1977. Even in the Loop itself, says de Vise, the work force is down slightly; what has expanded is not so much the number of Loop workers as the amount of square footage each worker consumes (professionals take up more space than secretaries). Far from serving as an inspiration to the rest of the city, the Loop and lakefront may well be a reverse image.

Many of the byproducts of the fifties and sixties Loop development are by now readily acknowledged by most Chicagoans. The high-rise office towers drove up property values and so drove the city's upper-middle class out to the suburbs, an exercise made that much easier by all those shiny new expressways. Meanwhile, the tall new office buildings replaced hundreds of little shops, restaurants, taverns, theatres, and nightspots that previously functioned into the wee hours. Within a matter of years during the 1960s, the Loop was transformed into a daytime-only city. The talk of an urban renaissance is especially ludicrous to anyone who ventures into the Loop at ten p.m. or to anyone who remembers a time, some 30 years ago, when it sparkled with legitimate theatre, repertory companies, good restaurants, jazz clubs, and cozy bookstores.

Belatedly, the city recognized that it might be a good idea to have people as well as buildings along Loop streets, so housing sprang up over the Illinois Central tracks, at the south end of the Loop (the new Dearborn Park project, for example) and on the north side of the Chicago River. These grandiose projects, in turn, will no doubt generate other grandiose and unforeseen problems, which will be addressed by further grandiose projects, and so the cycle will continue.

The trouble with grandiosity is that it leaves very little room for the sort of individual initiative that adds variety and spice to urban life. "People want the excitement of creating their own environments," says Harry Weese, a prime mover behind the loft renovations on Printers Row. The current lakeward migration of Yuppies, the renovation of old houses, and the conversion of industrial lofts into apartments have attracted so much attention largely because they are the first positive spontaneous occurrences in Chicago in years.

More to the point is a look at what has happened to State Street since it was converted to a mall last year—that is, nothing. Compare, for example, Chicago's State Street Mall to Philadelphia's Chestnut Street Mall. The two streets are very similar: Both are main shopping drags in the center of town, and both were converted to buses-only malls for about one mile at their busiest sections. But Philadelphia's Chestnut Street has always been a narrower street with smaller buildings—people-sized instead of auto-sized. When Chestnut Street Mall was opened in 1975, the place turned into a daily carnival, full of sidewalk vendors, musical groups, and magicians performing for whatever coins are thrown their way. A lunch-hour stroller can choose from a string quartet on one block, a ragtime band on another, and a calypso group on a third.

By contrast, State Street was just too big, too broad, too tall to make a difference. The only musical groups you find in the Loop are those hired by the First National Bank to play on its plaza. Carnivals occur on State Street only when the city commissions one.

"There's a kind of esprit that's the ultimate undefinable factor in a city," says Carl Condit, a professor of urban technology at Northwestern University. "It makes people believe in the city and work to make it a good place. Philadelphia, Boston, San Francisco, and parts of New York have it. Chicago had that spirit in the 1890s, when the great institutions were created—the Art Institute, the Field Museum, the University of Chicago, the symphony—and it had that spirit in the 1920s, when 20 percent of the city's present housing was built. But Chicago today is a city of conflict. Daley's philosophy was to build great concrete works, but the city was reckless in wiping out neighborhoods for expressways and buildings, and the new buildings that went up lacked the architectural richness and warmth that characterized the city's earlier boom periods. For the people who lived here, the city got to be a very abrasive place." Philadelphia's Chestnut Street does have one important geographical advantage over State Street. Chestnut Street actually goes somewhere—to Independence Hall and Philadelphia's tourist-oriented historic district. For that matter, most of the world's great streets—the Champs-Elysees, Pennsylvania Avenue, Fifth Avenue—connect some points of major importance.

State Street goes nowhere. It could have gone somewhere if, in the 1950s, McCormick Place had been built at, say, Roosevelt and State streets, instead of in Burnham Park. At Roosevelt and State it would have anchored the south end of the Loop as a desirable area and inspired the creation of hotels nearby (it would also, of course, have been more accessible by public transportation). But the city was in a hurry, the Tribune was pressing for a monument to its late editor-publisher, Robert McCormick, and 180 acres of Park District land were available at no charge and with minimal hassle, so McCormick Place was slapped onto a lakefront location where it was cut off from anything but automobiles and where its opportunities to benefit the city were minimized.

As Mayor Daley himself was fond of reminding his detractors, it's easy to criticize when you have the benefit of hindsight. In 1955, no one could have foreseen the energy crisis or the decline of the Loop. (Indeed, the preliminary study released that year predicted that McCormick Place would be the most accessible exhibition hall in the world.)

But precisely because unforeseen problems have a way of cropping up in any project, it's a good idea to avoid excessively massive projects—precisely the stuff Chicago has become addicted to.

The example of McCormick Place notwithstanding, a large institution usually becomes a neighborhood force for good or evil, depending on the institution. The reassuring presence of the University of Chicago, Michael Reese Hospital, Prairie Shores apartments, and Lake Meadows apartments on the South Side have played a role in stabilizing Hyde Park for the upper-middle class. The University of Illinois at Chicago Circle and the West Side Medical Center have performed a similar function on the West Side. McCormick Place could have played the same role for the south Loop, but the city blew the chance.

On the other hand, the two massive public-housing projects of the Daley years, Cabrini-Green on the West Side and the Robert Taylor Homes on the South Side, have served as negative anchors by scaring would-be middle-class pioneers away from those areas. Both projects have been attacked by social scientists as "vertical ghettos." The city has long ignored such criticism, but now it appears that Cabrini-Green and Taylor have committed a more serious offense, by Chicago standards: They are occupying choice real estate, or at least real estate that would be choice if they weren't there.

Consider what happened when a negative-anchor institution butted heads with a "positive" institution like Sandburg Village. Sandburg was conceived in 1955 as an attempt to pump new life into a seedy stretch of North La Salle by clearing 1,190 substandard housing units and replacing them with 2,590 new units, mostly apartments and townhouses. Sandburg was to become Sun City for singles, and its presence was intended to inspire a rebirth of the surrounding area.

To some extent, the plan succeeded. The opening of Sandburg gave the first impetus to the development of Old Town along Wells Street. Property values around Sandburg rose from a range of $80 to $600 per square foot in 1955 to $2,500 to $3,500 in 1975. But the Wells Street development turned sour, largely because of the sheer immovability of Cabrini-Green a few blocks to the west.

Given Chicago's infatuation with rising property values, it seems only a matter of time before Cabrini-Green, and possibly even the Taylor homes, are leveled—not for humanitarian reasons, but for economic ones. That will free more space for the new urban gentry while presumably pushing the poor farther out (not such a terrible idea, since most of Chicago's blue-collar jobs have drifted out to the suburbs already).

But even if the city takes the extreme step of destroying two of its hugest public projects, there remain limitations on the number of Chicago neighborhoods that can be regentrifled. The explanation can be found in a concept that retailers and architects call "incubator space"—that is, a place where an innovative craftsman, merchant, restaurateur, or theatre company can experiment with new ideas without worrying about overhead costs.

The ideal incubator space has two characteristics. First, it's on relatively inexpensive property. Second, it has access to a sizable population of taste, sophistication, and affluence. Old Town was a classic incubator space in the early 1960s until its commercial success drove property values up so high that "iffy" shops, clubs, and restaurants were pushed northward to Lincoln Avenue and New Town. Today some of the most innovative restaurants and theatres can be found farther north in the city's newest incubator spaces, along Clark, Elston, and Broadway.

Conversely, you rarely find an antique store, a crafts shop, a gourmet restaurant, a funky tavern, or a Zen Buddhist bookshop in a suburban shopping mall because the suburbs lack the critical mass of sophisticated population to support such ventures. You don't find them in the tonier parts of the city, either, simply because the rents are too high.

Pierre de Vise suggests that much the same theory can be applied to regentrification. In his 1978 study of Chicago's expanding singles housing market, he noted that the neighborhoods best suited for renovation are those that are not too successful to have been renovated before (so that house prices and rentals remain low) and not too far neglected to be beyond hope. Given these two requirements, de Vise concluded, "The list of potential neighborhoods that qualify for future renovation is not a long one."

How can Chicago generate a true urban renaissance? How can it make city life attractive to young professionals with children, at prices they can afford? How can it absorb great numbers of Yuppies—married or single—into the center of the city without displacing the poor? How can it provide all these nomads with some sense of roots, of civic spirit, of continuity between the city's past and its future?

There's a good answer to these questions, but it flies in the face of Chicago's mania for constant demolition and construction. The answer is simply to make better use of existing buildings and neighborhoods.

That is precisely what is happening in places like Printers Row in the south Loop, where vacant industrial buildings are being converted to reasonably priced (at least so far) middle-class housing. The flight of industry to the suburbs and the Southern states has left acres of empty buildings on the fringes of the Loop, many of which are now being converted for residences. The Yuppies who move into these buildings will have their cake and eat it, too: They'll get reasonably priced housing in a good location without displacing anybody.

But the biggest obstacle to such renovation may well be the city itself. Prior to the 1970s, the city enforced a law prohibiting the conversion of industrial lofts into residences—and the law is still on the books. Today the city's building code—one of the toughest in the country—remains a major stumbling block for people who would do anything with a structure other than tear it down and build a new one. Dozens of abandoned—but perfectly useful—industrial and railroad buildings have already been demolished by the city, so that ambitious projects like Dearborn Park and Printers Row stand amid vast wastelands of rubble. Between State Street and Canal Street lie some 400 derelict acres that returning suburbanites are unlikely to find very inviting. Of the first 198 buyers in the 939-unit Dearborn Park complex, only 22 percent have children under the age of 18.

The loft-renovation campaign, while certainly a good idea, is nevertheless another manifestation of the Chicago notion that anyone who's anyone must live in the middle of the city or along the lake. Actually, the city has an ample supply of decent, reasonably priced outlying neighborhoods that no one who's anyone has ever heard of. (See a list of five Chicago communities that fit the bill.) In a recent issue of Planning, Chicago planner Stephen Friedman suggested that if more Yuppies were aware that such reasonably priced housing is available, they might be more willing to have children.

"The suburban generation—intimidated by all but a few areas of the city—doesn't know about these neighborhoods," Friedman wrote. "When suburbanites move to the city, they want to make the neighborhood a sophisticated version of the suburbs they come from. That is why prices skyrocket when an area is discovered."

Friedman's solution is to gather city planners, real-estate brokers, bankers, and neighborhood associations to market the good-but-unknown city neighborhoods. Some cities, such as Boston and Baltimore, have active programs to promote neighborhoods. Chicago has none—as I discovered.

Posing as a Philadelphia middle-management executive considering a job offer from Inland Steel, I phoned the Chicago Association of Commerce and Industry, seeking information about good places to live. I was referred to the association's housing-services department. The enthusiastic director began ticking off the glories of the suburbs, where "the schools are terrific."

"My family and I would rather live in the city," I said.

"The city is terrific, too," she quickly assured me. "My husband and I just moved to the Near North Side after 24 years in the suburbs. It's wonderful—we don't even need a car."

"I'll bet your children are grown," I said.

"That's true," she said. "But there are very good schools in town. Friends of mine send their children to Latin. The tuition is $2,900 a year."

"What about the public schools?" I asked. "In Philadelphia, both my daughters attend very good public schools, right in the center of the city"—which is true.

I heard a sigh on the other end of the line. "Well," she said finally, "if you want to send your children to public school in Chicago, you'll have to check it out very carefully," with special emphasis on the last two words.

The next day I picked up the association's housing packet and saw its promotional film-strip, both of which touch on most neighborhoods but mostly dwell on the suburbs.

Now, you can't blame the association or its housing-services director for the information they provided me. They were extremely honest, especially in terms of the sort of guidance that an out-of-town young-executive father might need. But that guidance reinforced the image that occurs to most Americans, and most Chicagoans as well, whenever the word "Chicago" is mentioned: There are the Loop and the lakefront, and then there are the suburbs, and there's nothing in between. No wonder lakefront housing is so expensive, and outlying city housing is such a bargain.

(Come to think of it, when my wife and I first moved to Chicago in 1968, we hadn't the foggiest notion of where to look for housing. Our only rule of thumb was some advice we had picked up by word of mouth: Stay within four blocks of the lake.)

It may be too much to ask the city to stop knocking down neighborhoods and start promoting the ones that still exist. After all, construction unions have to eat. But the city is unlikely to have a truly pervasive urban renaissance until it readjusts its notion of what a city is all about. Some of the nicest things that happen in a city happen by accident—and the migration of Yuppies to Chicago's center is one such accident. Mayor Daley had no use for accidents; he bequeathed us the notion that the life of the city can and should be engineered from the top down and from the Loop outward.

"We must understand that it's better to live in a dirty, ugly city than in an antiseptic hospital," says Dominic Pacyga, co-author of Chicago: A Historical Guide to the Neighborhoods. Make no little plans, yes. But make no big mistakes, either.