We call each other Twin.

Been doing that for years. We share shit: height, weight, style, sneaker DNA (and size), ideologies, skin color, love for our people, this city. Not that we are a reflection of one another, but we reflect on each other.

“I remember the first time I met you,” LaVelle Sykes tells me. “You came into Tony’s Sports one day and it was like you were famous already. And I said, ‘I’ma be friends with this dude.’ ”

That day was in the mid-’90s. I know because LaVelle started working at Tony’s in 1994, two years after his cousin was killed, two years after he was in a car accident that nearly took his life (the same happened to me in 1987), a crash that forced him to make a choice: Find yourself or let these Chicago streets find you.

The former choice led him into what was — for us in Black Chicago — the “University of Urban Fashion”: Tony’s Sports under the Red Line stop on Sheridan. ’Velle was already a customer, but needed a life raft before he drowned in the Robert Taylor Homes concrete that raised him. Tony gave him a job. Stockroom. Thus began his hustle.

“Selling sneakers saved my life,” ’Velle says. “I promised God after the car accident, ‘If you get me out of this coma and let me walk again, I’ll become something.’ He woke me up and I became something.” I met ’Velle because he sold me my sneaks every time I stepped into Tony’s. He’d moved to the front of the store by then, behind the counter, over the cash register. I clowned him one day, asking, “Are you signing the checks yet?” Not joking, he said: “Not yet.” By 2001, ’Velle was running Tony’s business for him.

My mother always told me that the one thing America feared the most was a Black man with a plan. LaVelle had a hella plan. He noticed during his 12 years at Tony’s that there was a void in the sneaker retail business. “I wanted to have the first minority-owned sneaker boutique franchise in the city,” he says. So when he and Tony had a disagreement in 2004, ’Velle gave notice, quit, found an investor, kept the industry connects he’d built, started selling sneakers out of the trunk of his car, bought storefront property on a $30K loan, and in July 2005 opened Self-Conscious, his first store.

“What developed at Tony’s I took with me to Self-Conscious,” he says. He also took it to his next store, EnCore (get it?), which became the only high-end sneaker consignment store in the country at the time. No sneaker below $200. Bad and bougie way before Migos and the spell change. It lasted two months. Business deal goes left and he ends up in court with his investor. They found a way to settle without ’Velle losing his visibility equity. In the neighborhoods, they weren’t calling ’Velle’s stores by their names — back then, we were all like: “You going to ’Velle’s?” He’d personally become the brand of something he’d wanted to simply be a business. “V-Dot” is what everyone started calling him, associating his hustle directly to him, making him the Chicago focal point of a subculture that was moving into America’s pop culture bloodstream.

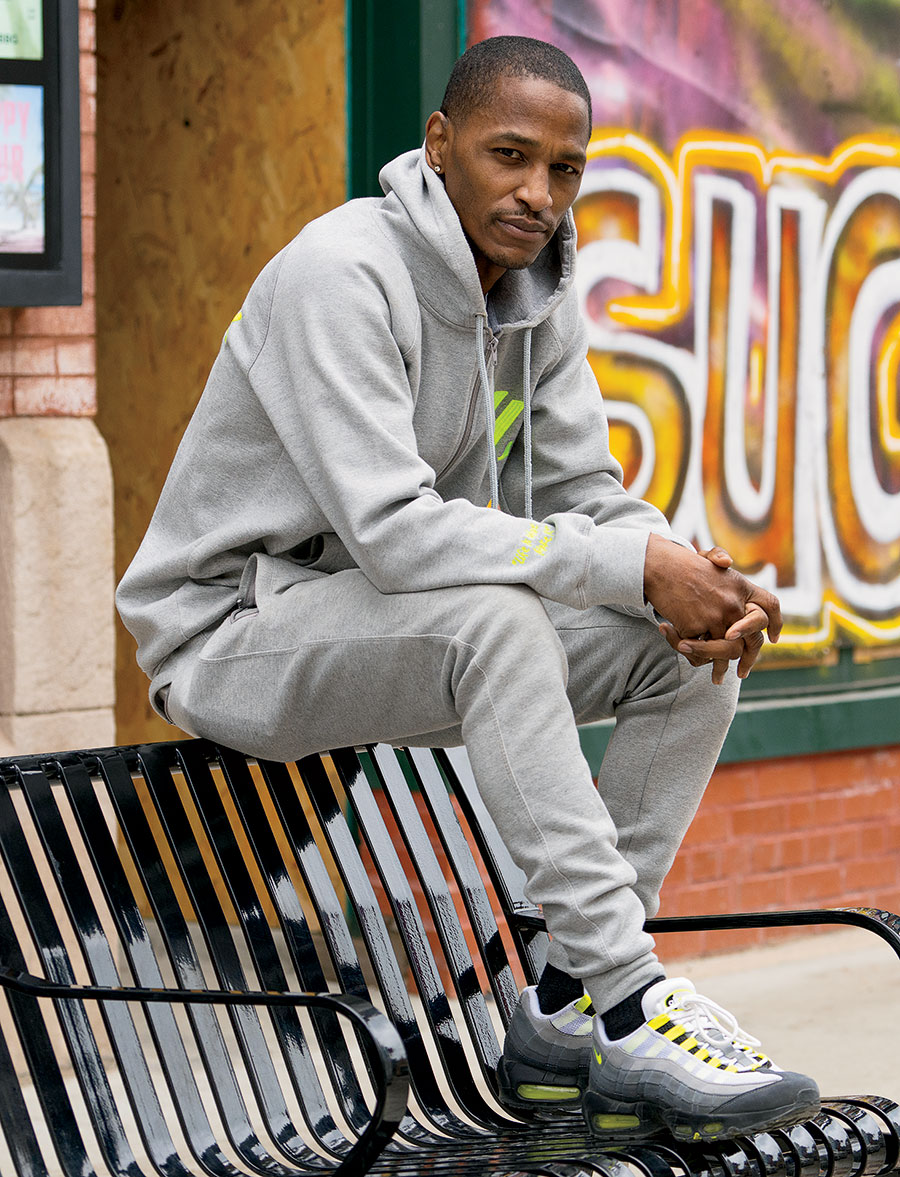

With EnCore closed, Sykes was without brick or mortar. All he had was inventory and ideas. One of those ideas found life in 2008, when he and former DePaul and NBA player Bobby Simmons opened up SuccezZ (“two z’s because we don’t sleep,” says ’Velle) on Michigan Avenue just off Roosevelt Road. Their come-up nothing compared to their sustain. Because over the next 10 years, it seemed as if the rest of the city (and country) finally caught up to ’Velle’s intuition on the societal relevance of urban fashion and sneakers. SuccezZ became one of the most prominent Black-owned retail spaces in the nation.

’Velle and I have watched each other dream our way through bars that wouldn’t bend, navigating careers through the racial and racist waters of industries — fashion for him, media for me — where the color of our skin had less to do with everything we’ve been forced to face than the color of our voices. Both of those industries telling us to shut up and shut up. The struggle more than real, every day attempting to suck the soul and culture out of us until we conformed. Then. Now. Still. The white-rise of counterparts who’ve done 10 times less yet benefited 10 times more. The weight that comes from trying to survive (literally) and thrive in a city with a rep for genocidal behavior while running small Black Chicago businesses in all-Black Chicago neighborhoods. As ’Velle puts it: “The corporate brands not letting you run your business like you want to run your business. Being a minority in this game, we get overlooked a lot — collaborations, funding, accounts, getting respect. Yeah, I have a brand, I have a store, but they’ve never acknowledged what I’ve done for this culture. I built this thing here in Chicago. I’ve never left it.”

I was with ’Velle the early morning of August 10 last year, when the hood we’ve always held up and tried to be examples for turned on him. He was sitting on his car across South Michigan Avenue from SuccezZ’s new location and watched it all unfold. One brotha saying to ’Velle as Black folx looted 16 years’ worth of his life business: “Just because you Black don’t mean shit.” Next to ’Velle and his wife as people and product left his edifice: a police officer. Sitting and watching, too.

A group of us got together the next day, going into salvage-and-recovery mode to get V-Dot’s spot back to where it had been (because that’s what we do: survive, at all costs). I sat in awe of how he’d already reconciled it all. “I was able to get past it because I saw that they needed it more than I needed it,” he said. “I know, because I was that kid that was hurting from something. And I cannot judge them without judging myself.”

What’d Nietzsche claim? What doesn’t kill you makes you Blacker? Or was that Damon Young? Either way. ’Velle’s Black, I realized, was Blacker than my Black in that moment. Twins, just not identical. “I wish I coulda given the merchandise to them,” he said. “I’d have rather give it to them than them take it from me. I grew up with these people. I am these people.”

I nodded in solidarity. His tone strengthened. “I see the crime every day, I see the violence, I see the murder, see somebody die every day, get shot, I hear the story every day, brah, like, I know these people. And that’s the hard part about this whole industry, and me being who I am. The dude who comes in my store to buy a pair of sneakers, he’s not just a kid from the corner: I know his moms, I know his dad, I know his auntie and uncle, I know his cousin. I know my people. These other stores, they don’t.”

There’s a hoodie that I walk around in that reads as motto and reminder of not only who ’Velle is but why we’re twins: “While I’m Watchin’ Every Ni**a Watchin’ Me Closely, My Shit Is Butter for the Bread, They Wanna Toast Me, I Keep My Head, Both of Them, Where They Supposed to Be.” Message by Hov, product by SuccezZ. A memorandum. Whatever affects one directly, affects the other indirectly. Tied in a single garment of destiny, we coexist.

Comments are closed.