John Dillinger’s Death Mask

Little documentation accompanied this macabre curiosity when it was donated to the museum by Charles R. Walgreen Jr., scion of the drugstore chain family, so its maker is not known. Death masks were not exactly commonplace in 1934, when the 31-year-old bank robber was gunned down by FBI agents, but given his fame at the time, one can imagine an enterprising coroner making a few to sell off. Indeed, other Dillinger death masks have turned up in private and public collections around the country. That crescent-shaped mark below the right eye? A bullet exit wound.

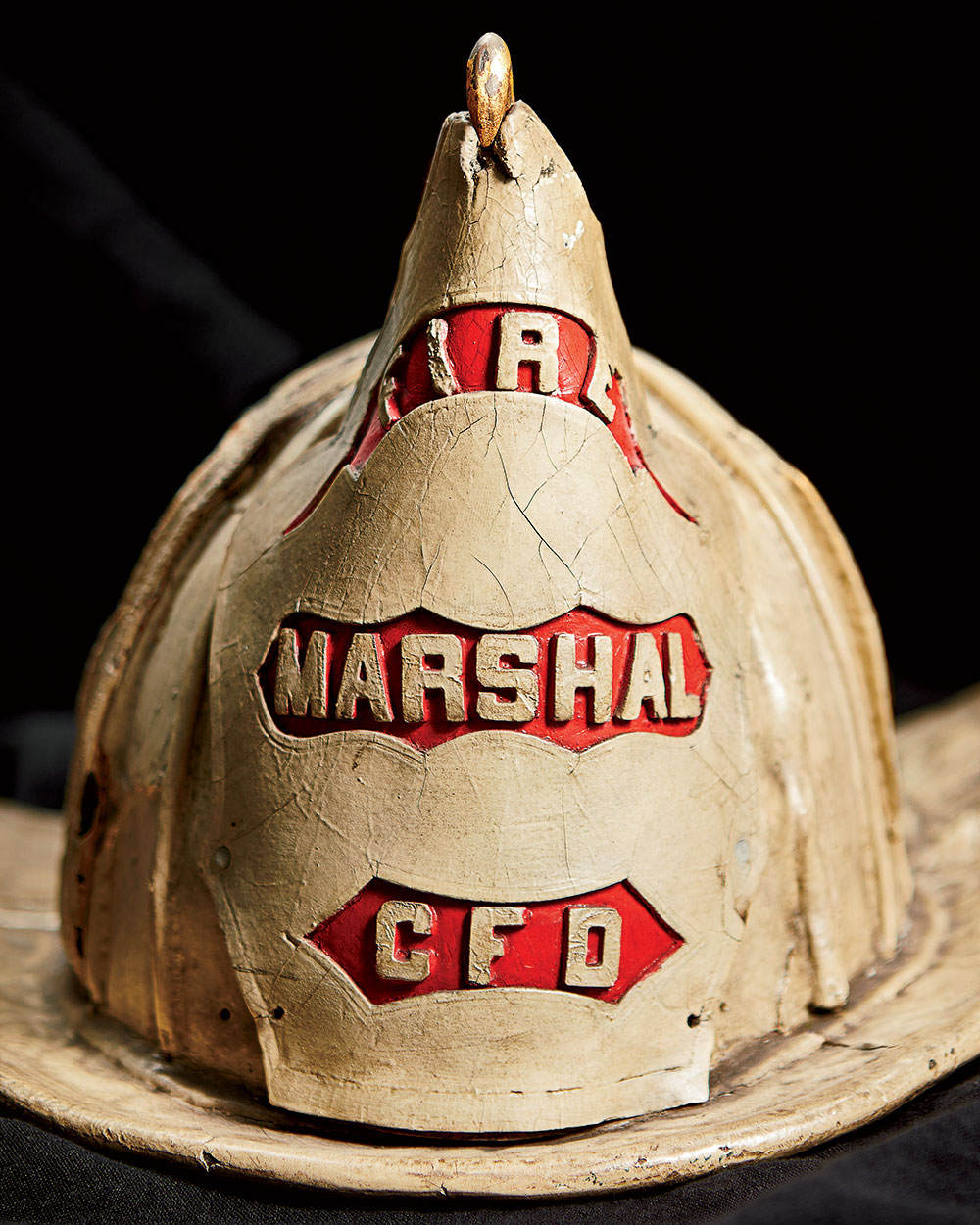

James Horan’s Fire Helmet

In the early hours of December 22, 1910, James Horan and dozens of other firefighters responded to a massive blaze at a meatpacking operation in the Union Stock Yards. The well-loved fire chief and 20 of his men died when one of the buildings caved in. It was the greatest loss of life for any city fire department in a building collapse until September 11, 2001. Horan’s white leather helmet was retrieved from the smoldering ruins and sat atop his casket in a funeral procession viewed by thousands.

Mary Todd Lincoln’s Fan

As any devotee of period movies or John Singer Sargent’s paintings knows, women of the Victorian era often carried fans, both for fashion and, in the absence of air conditioning, for comfort. This one, made of painted black chiffon, belonged to Mary Todd Lincoln, and while the museum’s collections experts can’t confirm it, the color suggests that Mrs. Lincoln might have carried this fan after her husband’s assassination in 1865.

Bertha Palmer’s Diamond Choker

The museum has a large collection of clothing and accessories worn by the famed turn-of-the-century socialite and philanthropist. This necklace, from around 1900, is adorned with several large European-cut diamonds and 1,169 smaller rose-cut ones; it was used to embellish a hat that Palmer was fond of wearing. How much is it worth? “For insurance purposes, we put a value on all our objects,” says senior collection manager Britta Arendt, “but we don’t share that information.”

Teacups Melted in the Chicago Fire

The museum possesses hundreds of objects rescued from the 1871 fire — or from its ashes. “A lot of people saved pieces like these as mementos when they returned to their homes and businesses,” says Arendt. These four white china teacups, donated by one Max Rosenfeld, who may have inherited them from a family member, were fused together by the heat of the conflagration, which destroyed three and a half square miles of the city. The streaks of color are believed to be melted glazing. (The teacups will be on display in October, as part of an exhibition commemorating the 150th anniversary of the fire.)

Abraham Lincoln’s Buckskin Moccasins

The tongues of these glass-beaded slippers — which for years belonged to the Lincoln artifact collector Oliver Barrett before being acquired by the museum in 1952 — bear the initials A and L. Arendt surmises that the moccasins were handmade for Lincoln as a gift. “If you look at ladies’ magazines from the 1860s,” she says, “you’ll see patterns to make slippers similar to these.” Whether Lincoln wore them is open to question: The 11-inch-long moccasins correspond to a size 11; Lincoln is said to have worn a 14.

Bottle of Prohibition-Era Whiskey

An inscription on the unopened bottle reads: “From the first shipment received after the repeal of the 18th Amendment in 1933.” The words were written by the donor, Lawrence O’Toole, whose father had apparently acquired at least some of that shipment and, presumably having quenched his thirst, set aside a bottle for posterity. A few ounces of the Chapin & Gore whiskey (which was sold as Kentucky bourbon even though it was distilled in Chicago) have been lost to evaporation, but what remains would be perfectly fine to drink.

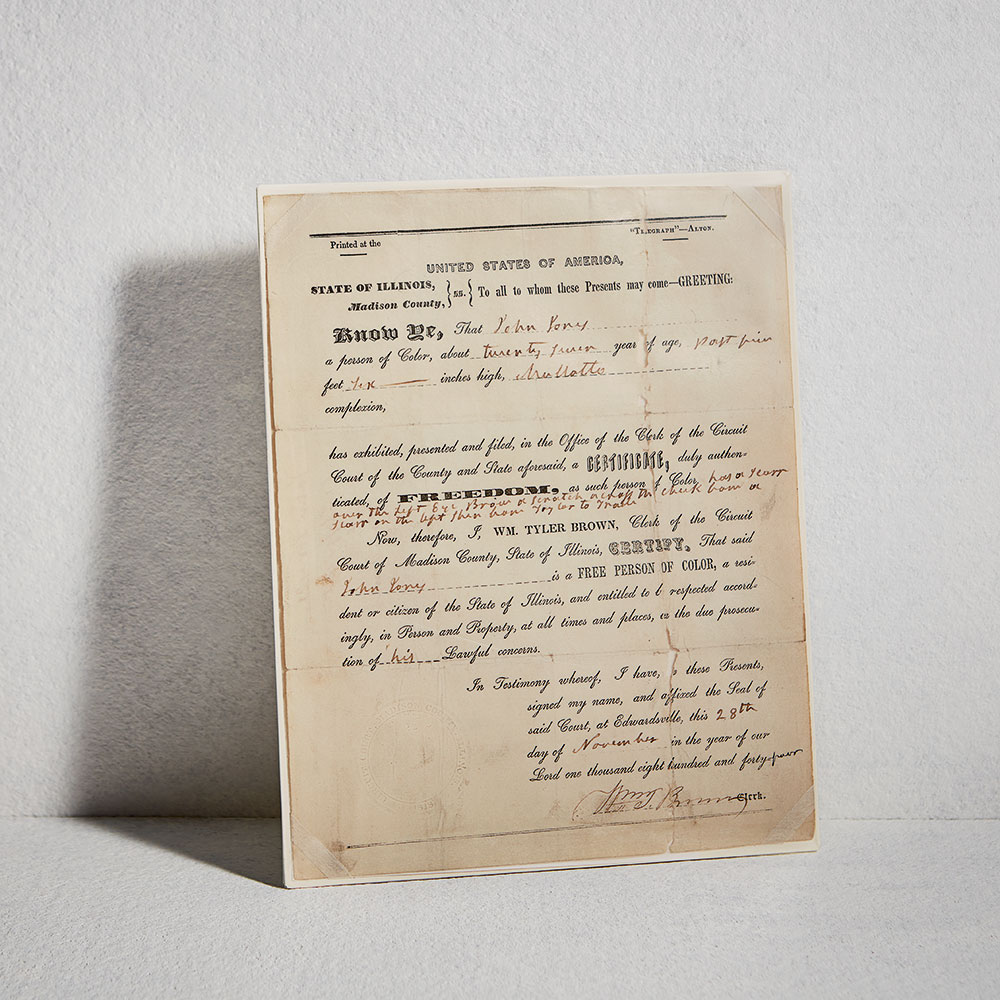

Certificate of Freedom of John Jones

This remarkably well-preserved document, drafted in 1844 by a court clerk in Edwardsville, Illinois, attests to John Jones’s status as a free man. (The museum has the nearly identical certificate for his wife, Mary.) The certificate gives a physical description of Jones and declares him “a resident or citizen of the State of Illinois, and entitled to be respected accordingly, in Person and Property, at all times and places.” This was a precious paper indeed, offering the formerly enslaved person at least nominal protection from being resold into bondage. Jones went on to become the first African American commissioner of Cook County.

Comments are closed.