For many Chicagoans, the area around Midway International Airport might as well be flyover country. After all, viewed through the window of a car speeding to the terminal or a plane landing on one of the airport’s runways, this corner of the Southwest Side looks like nothing more than ordinary bungalows and fast-food joints.

That isn’t how Chicago photographer Paul D’Amato sees it. The Columbia College professor has spent the last eight years documenting the often-overlooked neighborhoods — such as Chicago Lawn, Brighton Park, West Lawn, and Garfield Ridge — that surround Midway, snapping portraits of residents and recording scenes of a place that never stops moving. In this working-class slice of the city, jets roar so low that dishes rattle in kitchens. “Midway is a unique airport,” D’Amato says. “The houses run right up against it. It’s crazy — they’re like 50 feet away from the wall, and planes are landing within yards of it.”

The proximity makes for a study in contrasts. D’Amato views the Midway area as a place of transition: a diverse community of immigrants, first-time homeowners, and other strivers aiming to move up in the shadow of planes carrying passengers to far-flung destinations and freight trains rumbling through one of the country’s largest switching yards. Everyone, as D’Amato puts it, is midway between one thing and another.

D’Amato also captures the area’s mundanities: its chain restaurants lining Cicero Avenue and the quiet residential streets that could belong to any number of Chicago neighborhoods. The airport is merely a backdrop. As D’Amato has written: “It is a rock thrown in the middle of a pond of humanity with the economic and cultural ripples extending for miles in every direction.” Here he describes a few of his images.

“This is the pleasure of what I do: It’s amazing how a huge percentage of people that I approach, without having ever met before, and ask if I can make their picture say yes,” says D’Amato. “She said yes. I stopped my car, she looked good, I got her to stop the lawnmower — she was almost done — and then I realized, Holy crap, the planes are actually landing the right way right now. This is going to be amazing.”

“I’m mostly looking for opportunities to make pictures of people. But when there’s no one around and I see a space that is really interesting — that talks about the economy, the social strata of a place, like this does — it doesn’t need anyone in it. There’s so much literal energy. The banality of that driveway and this kind of generic brick structure, but these looming power lines — the tension between those things, that’s dynamic enough.”

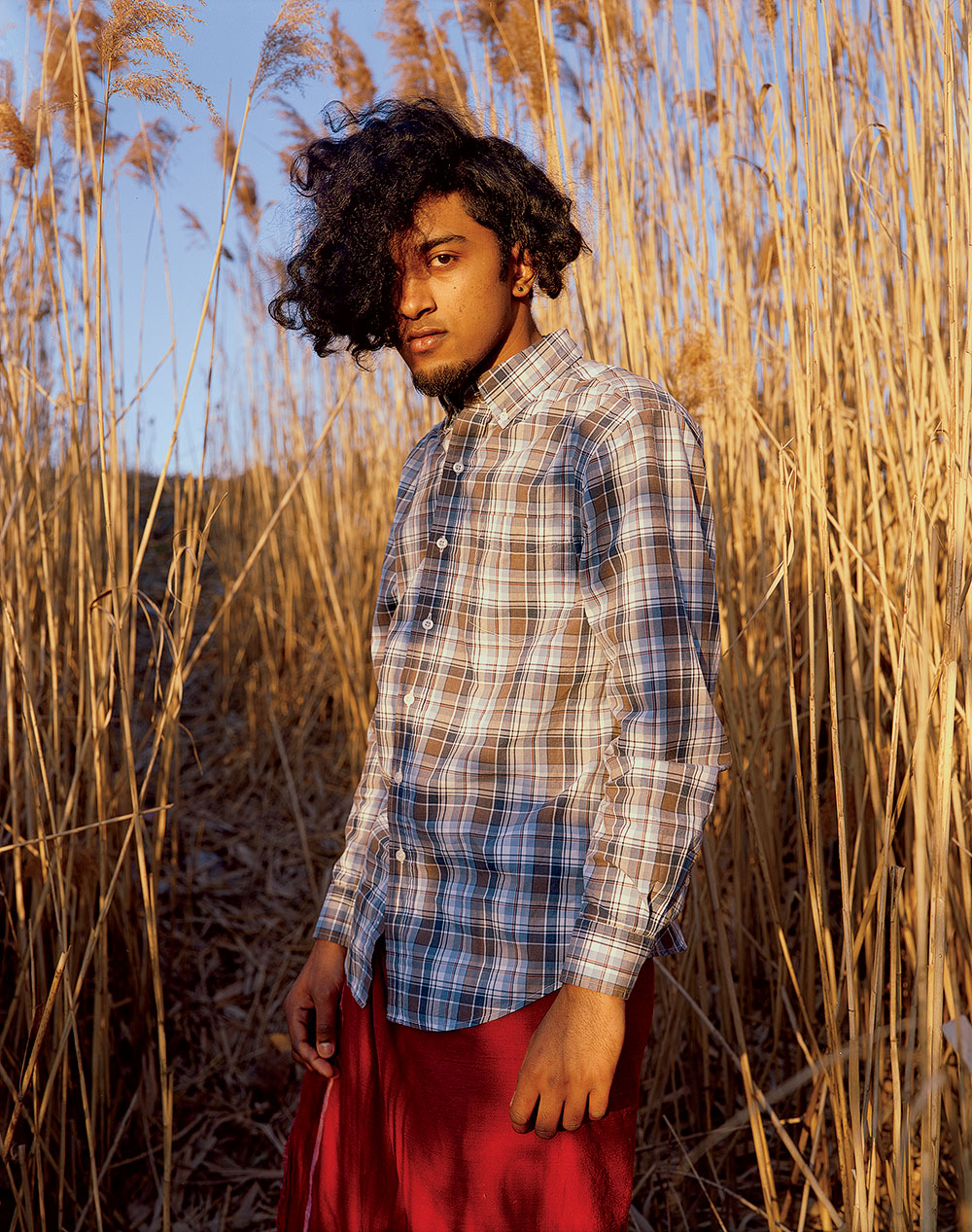

“He’s from a small village in southern India. I first photographed him when I got gas at the station he was working at across from the airport. This photo is the result of about four different attempts, possibly a year after first meeting him. This one I planned for days and is inches from the railroad switching yard.”

“They let it all hang out on the third of July. The whole place just lights up. This is an exposure that I kept making. If you’re in the street, you would remember all of those explosions. I’ve just added them together in one image. The guy who set all these off was working with me completely: ‘Are you ready for another one?’ We’d let a car go by, because that would ruin everything. This guy actually spent hundreds of dollars to help me make this picture, if you look at it that way.”

“What I’ve discovered by being involved in this community is that there is a kind of subculture of train hoppers, people who hop freight trains. Those freight trains are, like, right below that overpass. These are people who are passing through. Because all roads lead through Chicago. They’re homeless in the sense that they don’t have a home, but they’re not homeless in the sense that they’re rooted under a bridge. They’re travelers. I follow her on Instagram.”

“My wife was giving an artist talk – she’s a painter. And I was late for this talk. And there was traffic on Cicero, so I took the side street. And I saw this guy and I was like, ‘I’m sorry, honey, I’m going to be late.’ This guy is sitting there in a chair watering this dry piece of grass. It just seemed so emblematic of trying to make everything look like it’s reached a certain standard of acceptance. Trying to get that one patch to conform with all the others.”

“This photograph was made at the Karolinka Club, which famously used to be called the Baby Doll Polka Club. As you can see, it is just a few feet from the western wall of the airport. It’s still very Polish and is a holdover from when this used to be one of the largest Polish communities outside of Poland. This guy was just smoking while the jets were taking off every five to seven minutes.”

“I literally left rubber on the road turning the car around, pulled up right next to him. He was about to get in and go. His wife was already in the car. I talked them into this picture. I photographed him, and I saw her looking through the window. Oh, she looks amazing too. I got her to get out of the car, come around.”

“What always struck me about this street, which is not that far from the airport, is this huge ash tree that’s on the left. I’m kind of a tree-hugger — I know that ash trees are this endangered species. To see this ash as this last surviving majestic thing towering over these little bungalows was so interesting to me. And I’ve photographed that tree, like a portrait, I can’t tell you how many times. I was ready to do that again, because the light was awesome, and this guy comes out. He looks like kind of a guy you wouldn’t want to talk to. Turns out, he’s one of the nicest guys ever. He wants me to have a beer with him. And he tells me he’s doing everything he can to keep this tree alive.”

“This is a train yard right near Midway. Cicero Avenue goes right through the middle of it. And I photograph these birds all the time. I could have a small book of these birds. Only in the winter do all these pigeons hang out on these wires. I like the metaphor of the birds on a wire for all these people in bungalows — they’re there for a short while and they’re moving on. It’s part of the mobility of the community.”

“I like how unique Tony’s Kitchen is. This diner is not part of any chain. There’s not a lot dramatic that happens in this area. She’s a waitress, she’s trying to support her child. That’s him with her. She’s doing what you have to do. And even though a lot of Midway is marked by a genericness of fast-food places and motels, there still are the older places there. This place I think has probably been a diner forever and has changed hands.”

“The poetry isn’t in the story behind the picture. It’s a man, he’s got a family, he’s grilling. So who cares? It’s how you construct the picture, where it adds a certain gravitas to it. This is not a big Weber grill. This thing is barely standing. The poetry is in the way he’s seen. The way he’s framed as kind of this heroic figure. He’s like a figure on a Greek temple. This flame is, you know, the eternal flame. Why not?”