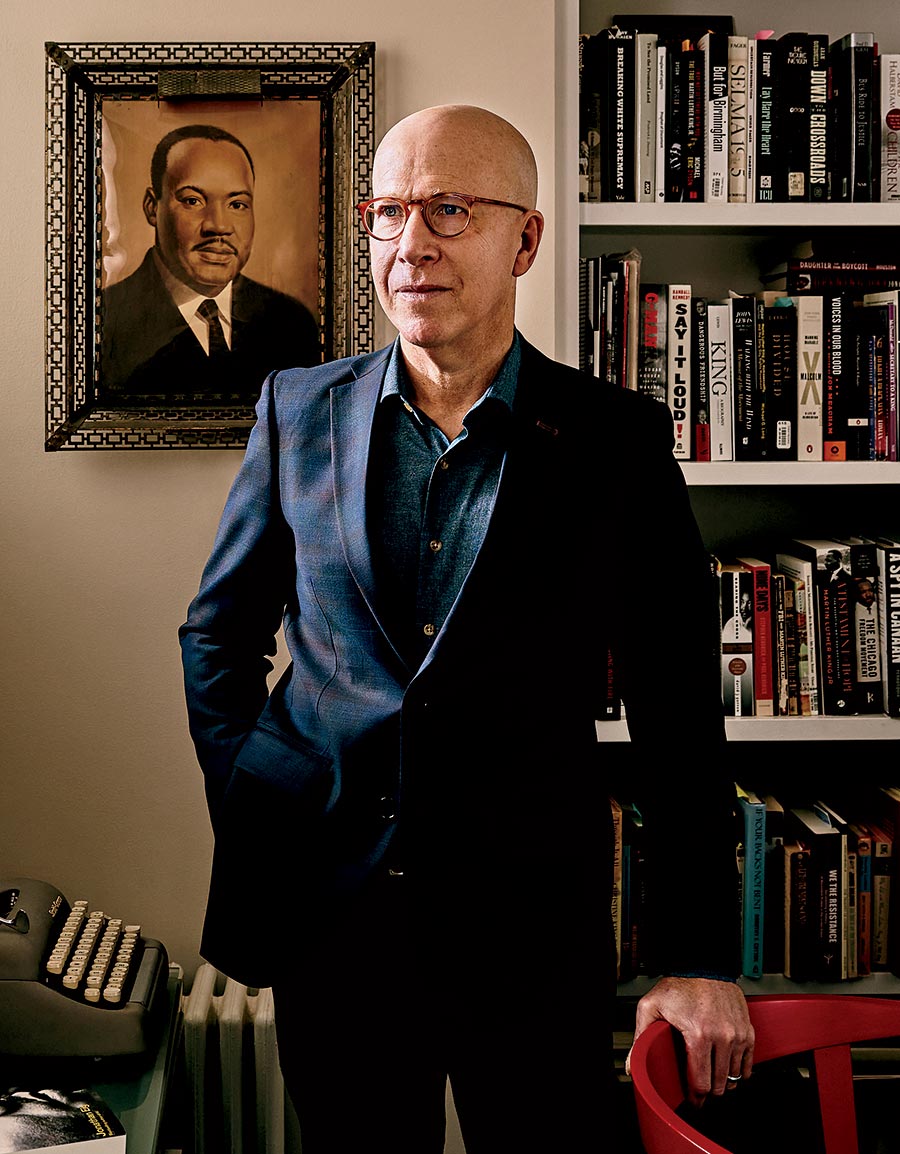

Though he was born more than 150 years after the Declaration of Independence was signed, Martin Luther King Jr. should be considered a founding father of the United States, Chicago writer Jonathan Eig argues in his book King: A Life, out May 16. After all, King led a movement that forced the country to live up to its creed that all men are created equal. “If you believe that those documents really are committed to the life of all and freedom and rights of all citizens, then it was incomplete until Black people began to demand their own inclusion,” Eig says.

His sweeping biography chronicles the civil rights activist’s journey, starting long before his birth and ending with his assassination on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. In this poetically written and deeply layered life history, Eig reshapes the image of King from a pacifist preacher to a radical revolutionary.

So many books have been done on Martin Luther King. Why write a biography of him now?

I was shocked to discover that it had been 35 years, and now 40 years, since the last King biography. That’s just much too long. And in that time, we’ve turned him into a two-dimensional figure. We’ve watered down his story — his radicalism in particular. We’ve turned him into a national holiday and a monument. We start learning about him in kindergarten, and sometimes we don’t get more complicated than that kindergarten lesson. I wanted to write a book that would be more intimate than the King books that have come before. I want you to experience the highs and lows, and I want you to cry at the end when we lose him. There was also an opportunity to do it now while there were still people alive who knew him really well: his associates, family members. And that window was closing fast.

How did you go about reporting the book?

I began six years ago. My first interviews were with Dick Gregory, Harry Belafonte, Andrew Young, and John Lewis. I traveled around the country before COVID, interviewing as many of these people as I could. I got to know people like June Dobbs Butts, a good friend of King’s from childhood. And I walked through the houses where he lived and walked through the streets where he played as a kid. It was essential to put myself in those places. I also did lots of archival research, including going through new FBI documents that had been declassified and going through this amazing collection of papers at the Schomburg Center in Harlem. My favorite part was the interviews. The opportunity to interview people who knew Dr. King — what a thrill, what an honor to record their stories, knowing that time was running out.

King said he hadn’t seen such hostility and hatefulness as he did when marching in Chicago. What did you learn about his time here?

We do King a disservice when we talk about how he failed in Chicago or how Mayor Richard J. Daley outsmarted him. King showed enormous courage in coming here and saying to the nation that Northern racism is more intransigent and more damaging than Southern racism and you need to open your eyes to it. He came here and offered concrete solutions. There weren’t just a bunch of marches to call attention to the problems. He offered the city steps for improving, and the city turned him down. Daley shut it down. That’s not King’s fault. That’s our own fault, our leaders’ fault, because they weren’t serious about making change. There’s a reason Chicago remains one of the most segregated cities in the country. We had an opportunity to do something about that when King was here. We’ve had many opportunities since then. But change is hard — there has to be a will for it, and Daley clearly didn’t have the will for it.

Your epigraph comes from Genesis: “Behold, this dreamer cometh … Let us slay him … And we shall see what will become of his dreams.” As you tell the story of King, from his birth and formative college years to his role as an activist and civil rights leader and then ultimately to his assassination, the pace and intensity rises, crescendoes, and then falls. Did you intend to tell the story in the format of a Gospel sermon?

You can’t write about King without writing about God, without writing about his beliefs. Jesus guided so much of what he did. There came a point in the book — the chapter after he gave the “I Have a Dream” speech — when the FBI began to turn up the heat and intentionally set out to destroy him. I was getting angry and I began to feel like I was preaching a bit. I had a sermon. But I’m not actually preaching. The facts tell the story. I did begin to feel really like something important was happening. We went from a moment of incredible hope — where many people feel like this country might turn a corner and overcome some of its racism — and our own government decided it was not going to let that happen. That it was going to take this man down before he became too powerful. I became very emotional about that, and that’s when I knew what the book was about. And that’s when I found and added the epigraph.

Not only do you chronicle King’s victories, you document his most troubling moments, like his extramarital affairs. Why go there?

I know that some people see King as a saint, and it’s difficult to acknowledge that our saints have flaws. But King acknowledged that himself. He didn’t get into details, but in many, many sermons he admitted that he was weak and that, like all of us, he struggled. When we are honest about it, when we acknowledge that our heroes have flaws, then we can better emulate them. We can try to live up to what they inspire us to do and not feel like we have to be perfect, too.

A Taste of King: A Life

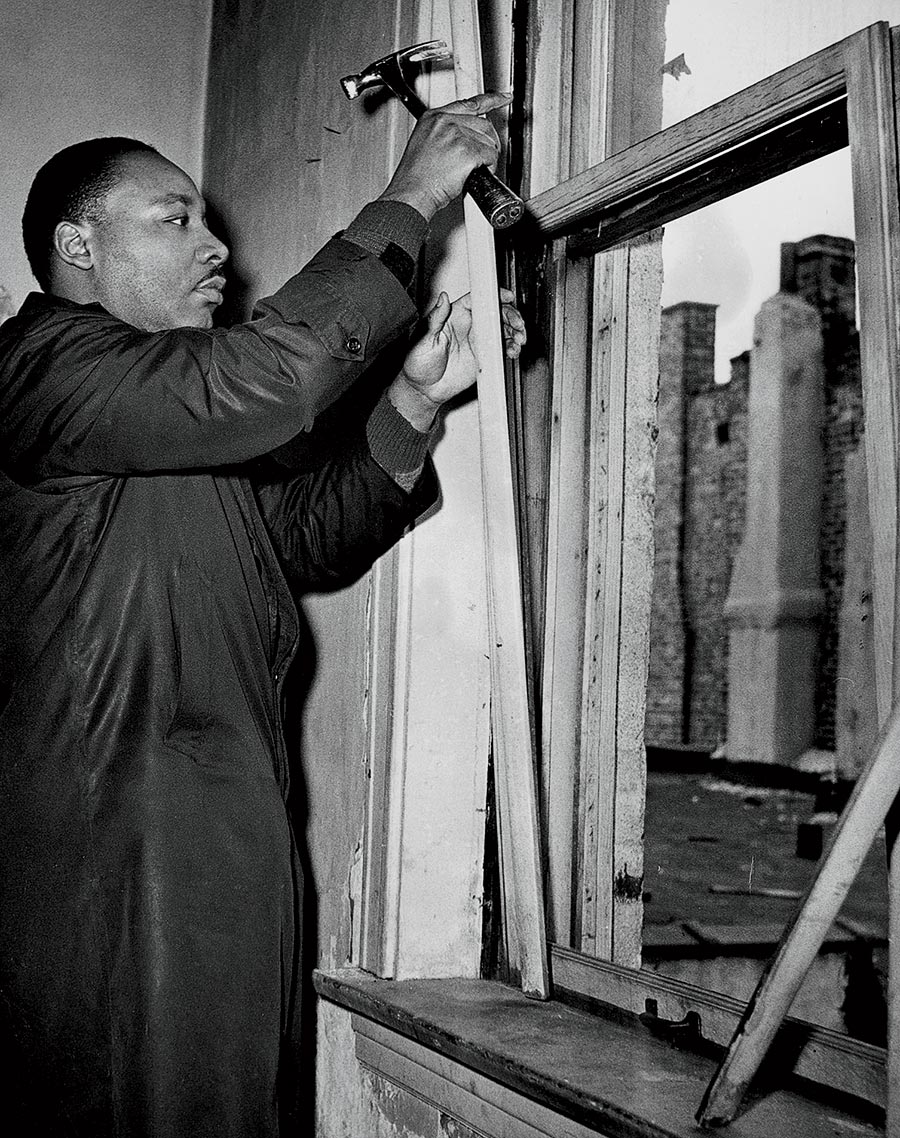

A sample from Eig’s chapter about the reverend moving into a North Lawndale apartment in 1966 to bring attention to redlining in Chicago and living conditions in its blighted neighborhoods:

On his first night in Chicago, King held an open house, inviting neighbors to visit. He talked for a long time with six members of a local gang, the Vice Lords, about Gandhi and the concept of peaceful protest. Everyone, including King, sat on the floor. “We would say, ‘We respect what you’re saying, but if someone hits me, I’m going to hit him back,’ ” recalled Lawrence Johnson, one of the Vice Lords. King argued that the gang members would never win that way. The police would always have more power. “Hearing this, seeing him, being young, living in a depressive life in America, you couldn’t help but to fall in love with him,” Johnson said.

Despite the admonishment, the Vice Lords believed there was at least one thing they could do better than the police: protect Dr. King.

“I think he thought that, too,” said Johnson.