Once a powerhouse among chicago corporations, sara lee has struggled in recent years. Can brenda barnes, one of the few women running a fortune 500 company, find a new recipe for success?

|

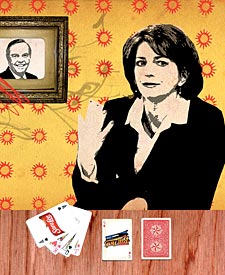

illustration: Michelle Thompson/agoodson.com

|

| Barnes was “dealt a difficult hand,” one observer says of the troubles she inherited from previous CEOs John Bryan (pictured) and his successor. |

Sara Lee Corporation was at the top of its game in the early 1990s, comfortably perched near the summit of Chicago’s corporate community. The consumer goods conglomerate averaged profit gains of about 14 percent each year on a portfolio of businesses that included Hanes underwear, Bali bras, Coach leather goods, Ball Park hot dogs, and Jimmy Dean sausages. Its stock was a bright star on Wall Street. Chief executive officer John Bryan traveled to Europe, often to keep tabs on operations in French hosiery, Dutch coffee, and English tea. Back at Sara Lee’s corporate offices high above the Loop, Bryan showed visitors a collection of impressionist paintings by Pissarro, Morisot, Matisse, and Degas. He raised millions for civic causes like Symphony Center.

Fifteen years later, Sara Lee is struggling to reinvent itself after a series of write-offs and restructurings and even a guilty plea on a misdemeanor count in a food poisoning case. Its shares were down 25 percent in the 18 months preceding the spinoff in September of its Hanes apparel business. One analyst, Edgar Roesch of Banc of America Securities, this year ranked Sara Lee dead last among its peer group of nine consumer products companies because of slow growth, relatively high costs, and a lackluster strategy.

“It has broken my heart to see what [the company] was and where we are now,” says Beatrice Cummings Mayer, daughter of Sara Lee’s founder, Nathan Cummings, and a former director.

Chief executive officer Brenda Barnes, one of only 11 female CEOs of a Fortune 500 company, no doubt recognizes her company’s troubled situation. She has led a radical restructuring, having shed 40 percent of Sara Lee’s businesses and, for the first time, put the remaining operations under a single roof. But Wall Street is impatient for results, and investors wonder if there’s a future in a company limited to humdrum products such as bread and hot dogs. “I don’t see anything exciting in the portfolio that enables them to be more than an average packaged foods company,” says Greggory Warren, an analyst at Morningstar in Chicago.

Sara Lee’s decline is a case study in the difficulty of prospering in a fluid economy. Globalization and the rising power of Wal-Mart Stores and other retailers have put the company in a defensive position. Even changes in fashion have hurt-once a source of strength, the L’eggs pantyhose brand was tattered after working women gave up hosiery for slacks.

But some critics see Sara Lee as a victim also of executive complacency. They say that the company’s managers and outsiders never adequately confronted Bryan about the company’s lagging performance as the decade wore on. “His track record earned him deference,” says Janet L. Kelly, Sara Lee’s general counsel between 1995 and 1999. “He had been very successful. Was this just a bad patch?”

Today, the burden falls on Brenda Barn es, 52, although she can hardly be blamed for the mess she inherited from both Bryan, who retired in 2000 after 25 years, and from his successor, C. Steven McMillan. “The clock is ticking on her,” warns Timothy Ramey, an analyst at

D. A. Davidson & Company in Oregon and a former vice president at Sara Lee. “The board didn’t sign up for $14.50 per share”-the price of the stock in early September.

Fairly or not, Barnes draws particular scrutiny as one of the few high-profile female CEOs and because of her decision in 1997 to step down as CEO and president of Pepsi-Cola North America to spend more time with her family. At the time, her choice became a flash point in the dialogue on high-powered career women-they couldn’t have it all, after all! But when she accepted the number two job at Sara Lee seven years later, and then the top position-well, maybe they could. Forbes this past summer ranked Barnes as one of the ten most powerful women in the world, ahead of Oprah Winfrey and Hillary Rodham Clinton, making her the highest-ranked Chicagoan on the list.

One can’t help but wonder whether Barnes understood the severity of the problems at Sara Lee. She won’t say-she declined to be interviewed for this article. A Sara Lee spokeswoman declines comment on Barnes’s progress as CEO and on Bryan’s legacy. Barnes, in the company’s most recent earnings report, says she is “confident that the progress we have made with the transformation of Sara Lee during fiscal 2006 gives us the foundation we need for strong future performance.”

Bryan became known as a deft manager but also “a prodigious fundraiser, to our great civic advantage,” says a foundation president.

But critics already have questioned some of her rescue tactics. For example, by announcing her plan to divest assets, she may have hurt Sara Lee’s ability to draw top dollar because potential buyers could smell a fire sale. And Barnes made promises that she couldn’t deliver. She vowed, for example, to maintain the company’s dividend but then had to reverse her position, cutting the payout in half to 40 cents a share. And after promising to achieve an average operating margin of 12 percent by 2010, the company backtracked and confirmed what many analysts were saying-that the goal wasn’t attainable. “She didn’t leave herself wiggle room,” Warren says.

Recently, there have been some modest signs of improvement, but not the sharply better financial results that cheer investors. “She was dealt a difficult hand,” says Sheli Rosenberg, the retired president and CEO of Sam Zell’s Equity Group Investments who knows Barnes through the Chicago Network, an organization of high-ranking professional women. “Wall Street wants tomorrow’s profits today and if they’re not delivered, it’s pretty merciless.”

Sara Lee traces its roots to 1939, when the Canadian businessman Nathan Cummings started to put together the conglomerate that would be known as Consolidated Foods, based first in Baltimore and then settling in Chicago during World War II. He acquired the bakery business known as Kitchens of Sara Lee in 1956 from the entrepreneur Charlie Lubin, who named a line of cheesecakes after his daughter, Sara Lee. Consolidated adopted Sara Lee as its corporate name in 1985, but the line of frozen baked goods represents only a fraction of sales.

“Dad was building a cluster of companies,” Beatrice Cummings Mayer recalls. “He bought companies that had a history of profits and had the number one or number two positions. But if they didn’t perform, he would sell the company, recycle the cash, and buy another company.”

John Bryan joined the company with the 1968 acquisition of his family’s Mississippi meatpacking business. He impressed Cummings, who enjoyed tutoring his protégé in collecting art, particularly works of the French impressionists. Bryan assumed the CEO post in 1975 at 38. The acquisitions of Hanes Corporation and Dutch coffee producer Douwe Egberts in the late 1970s fueled growth during the 1980s and marked Sara Lee’s emergence as an early multinational. Foreign operations-mostly in Europe-represented nearly a quarter of sales by the mid-1980s. The conglomerate model dictated a decentralized organizational style that worked well for a while because it cushioned cyclical peaks and valleys: if one business was having a bad year, the strong results of another usually would more than compensate.

As Sara Lee flourished, Bryan became known not just as a deft manager but as a patron of the arts. In the early 1990s he led a campaign that raised $100 million for the Lyric Opera of Chicago and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to put toward renovations and expansions. He donated a corporate art collection estimated to be worth as much as $100 million to several museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago. And Bryan is probably best known for spearheading the private-sector initiative for Millennium Park that raised more than $200 million from individual and corporate contributors. “He is a prodigious fundraiser to our great civic advantage,” says Sandra P. Guthman, president and CEO of the Polk Bros. Foundation. ( Chicago magazine named Bryan a Chicagoan of the Year for 2004 for his fundraising efforts.)

A Renaissance man and big thinker, Bryan seemed to enjoy holding forth on macroeconomic trends such as globalization, economic growth, and consumer confidence, whether he was addressing an audience of hundreds at an Economic Club dinner or shareholders’ meeting-or a lone reporter.

Bryan’s backing of fellow Southerner Bill Clinton in Clinton’s 1992 presidential run led to speculation that he would land some post in the administration, perhaps an ambassadorship or even secretary of commerce. It would have been the perfect crown to a distinguished career, but an appointment never materialized. Instead, Bryan remained on until his retirement in 2000. By then Sara Lee’s growing problems had tarnished the company’s image. Earnings dipped for the first time in 1993, as women began replacing their pantyhose far less often, damaging L’eggs and the recently acquired overseas hosiery businesses.

The disappointing results pointed to some structural weaknesses. For example, Sara Lee’s decentralized structure was a good way to motivate managers who had to produce profit-and-loss statements and were therefore accountable for performance. But that also meant that Sara Lee couldn’t provide an attractive career path to talented consumer goods marketers compared with centralized rivals who could offer more varied brand assignments. “Are you going to choose a $500-million unit of Sara Lee [to work for] or a much bigger company like Procter & Gamble?” Ramey asks. “The Sara Lee job was much smaller.”

And because Bryan had adopted the conglomerate style, acquisitions and divestitures received the most attention of top brass. The company constantly reshuffled the deck. Bryan bought and sold dozens of companies during his 25-year tenure-promising names came into the stable such as Kiwi shoe polish, Coach leather goods, and Playtex and Bali bras. But no one business ever emerged as dominant-like cheese at Kraft Foods or ketchup at H. J. Heinz Company. “It’s a collection of unrelated brands,” says Robert S. Goldin, executive vice president of the Chicago food consulting firm Technomic.

Analysts and former executives say the company too often resorted to financial engineering-finding ways to boost earnings or improve key ratios and measures that would please Wall Street. It wasn’t too difficult, for example, to cut an underperforming unit’s advertising, marketing, or development expenses to boost the bottom line. But that often came at the cost of building the brand.

The company ranks as one of the smaller packaged goods advertisers, according to an analysis by Sanford C. Bernstein & Company in New York. For example, Sara Lee’s spending on measured media (such as magazines, television, and radio) as a percentage of its U.S. retail sales was 3.9 percent, ranking it sixth out of eight food companies in 2004, the last year for which figures are available.

And the company lacked product innovation. Kraft Foods’ Oscar Mayer packaged meat business, to mention one rival, reaped healthy profit margins on its Lunchables line, which appealed to time-strapped families.

To be sure, all packaged goods companies were put on the defensive by the growing power of retail customers, especially Wal-Mart, which pressures suppliers to take thinner margins in the quest to drive down prices. “[Sara Lee] could no longer raise prices, and they were inefficient,” says Warren, the Morningstar analyst. “They had lived off the fat of the land for too long.”

Sara Lee responded to the tougher economic environment with a series of restructurings. It even launched a program it called “deverticalization,” or selling off its plants, including many textile operations in the South. But former executives say that strategy smacked of more financial engineering and did not address deeper fundamental problems.

Despite the downturn in fortunes in the 1990s, Bryan had helped build a huge business. During his 25-year tenure, Sara Lee stock increased 36.7 times in value, compared with 18.2 times for the S&P 500 index. But the returns began to falter. For the ten years ending in June 2005, Sara Lee stock appreciated by just 40 percent, while the S&P 500 grew at three times that rate and Sara Lee’s peer food group grew by twice as much.

Bryan, now 70, declined a request for an interview, saying that it would be inappropriate to comment because he left the company six years ago.

It may not have been evident to Wall Street or the Chicago business community, but former executives say today that Bryan grew bored and disengaged as the nineties wore on-seeming to show more interest in the symphony than in profit margins on socks and shoe polish.

Few executives discussed-at least openly-the leadership void at the Loop headquarters, and the circumspect Bryan showed no sign he was dismayed or restless. The decentralized structure and diversified product portfolio increasingly worked against Sara Lee, as investors looked for companies with a narrower focus. Was it a food operation or an apparel company? Wall Street couldn’t figure out how to value it.

Bryan’s final 18 months included some of the worst moments of his tenure. At the end of 1998, Sara Lee recalled 35 million pounds of Ball Park hot dogs and lunch meat amid an outbreak of listeria poisoning that led to 15 deaths, as well as six miscarriages. It was considered the most lethal U.S. case of foodborne illness in 15 years. Yet the story never generated much publicity, whether because it competed for headlines with the Clinton impeachment and his ordering of military strikes in Iraq or the government’s caution in handling the case.

No Sara Lee business emerged as dominant-like cheese at Kraft foods. “It’s a collection of unrelated brands,” says an industry consultant.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ultimately found the deaths had been caused by the meat processed at Sara Lee’s Bil Mar Foods unit in Zeeland, Michigan. The company pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of selling tainted meat-the settlement stressed that the company didn’t knowingly distribute bad meat. It also settled a class action suit and five wrongful death suits for a combined total of about $6.6 million.

Succession planning was another problem for Bryan. The number two, or president’s, position had been a revolving door under his tenure. When Bryan’s protégé, Steven McMillan, became president in 1997, he was the fourth person to hold that title in nine years. A former McKinsey consultant, McMillan had been in charge of strategic planning and was considered a master of the mergers and acquisitions game. But he may have been better known for his expensive taste in clothes and cars-he collected Harleys, drove Ferraris, and at one time raced Formula 2000 cars.

In 2004, a 35-year-old Dallas woman and a friend of McMillan’s daughter filed an employment discrimination suit against him and Sara Lee, charging that McMillan rescinded an offer of a $140,000-a-year marketing job after she broke off their affair. The case was settled in December 2004, but McMillan’s tenure wasn’t. Months earlier, he had hired Barnes as president and chief operating officer. In February 2005 she was elevated to CEO, the same day Sara Lee announced a “bold transformation plan to drive long-term growth and performance.” The company would focus on packaged-meat, bakery, and food-service operations in the United States, as well as beverages and household products in Europe, and divest noncore businesses. That would eliminate Wall Street’s confusion as to whether Sara Lee was a food or apparel company.

The final changing of the guard came at the company’s annual meeting of shareholders the following October, when Barnes assumed the chairman’s post and McMillan retired. In Barnes’s first year, revenues rose marginally to $19.3 billion, but diluted earnings fell more than 43 percent, to 90 cents per share, partly as a result of restructuring charges. Operating income fell by a third, to $1.1 billion. Shares slid from $22.32 when Barnes took over, to about $19 six months later, and continued downward to about $16 in late June of this year.

Barnes wasted no time abandoning Bryan’s decentralized structure and put in place a model more typical of the packaged goods business. She relocated corporate headquarters from Chicago to Downers Grove, incorporating bakery operations from St. Louis, packaged meats from Cincinnati, and beverages from Rolling Meadows. “Imagine John Bryan in Downers Grove,” quips Gordon Newman, a former senior vice president and general counsel who retired in 1995, underscoring how much the old company was tied to Chicago’s cultural life.

The new structure should pave the way for a coordinated strategy to market and promote brands-consumer deals as simple as a coupon for Sara Lee hot dog buns with the purchase of Ball Park hot dogs. And Barnes has touted to employees and analysts several innovations, including kid-friendly Soft & Smooth bread, which combines the nutrients of whole grains with the taste of white bread.

But Barnes’s decision to jettison businesses is somewhat more controversial, if only because investors aren’t sure of the value of what will be left. In rapid succession, she sold Sara Lee’s U.S. retail coffee business, which included the Chock Full o’Nuts brand, to an Italian buyer; the European nuts and snacks business to PepsiCo; European underwear brands to a Florida private investment firm; and the European meats business to Smithfield Foods. Barnes took a different approach with Hanes (annual sales: $4.5 billion), spinning off in early September the maker of the Champion, Bali, Playtex, and Wonderbra brands to shareholders, who received a share in the new company, Hanesbrands Inc., based in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for every eight shares of Sara Lee stock they owned. (In all, Sara Lee expected to raise $3.7 billion from the divestitures, including a one-time payment of $2.4 billion from the spinoff of Hanes.)

There’s hope that Hanes, as a stand-alone company, will do better, in much the same way that leather goods maker Coach took off after its 2000 spinoff to shareholders. The stock of Coach, which makes high-end purses, shoes, and accessories, has soared nearly tenfold and its market capitalization recently surpassed that of its former parent.

Former executives say Bryan grew disengaged as the nineties wore on, more interested in the symphony than in profit margins on socks.

Barnes has told investors that she isn’t wavering in her commitment to grow Sara Lee at rates ahead of the industry. And with the restructuring complete, greater efficiency and new products are the order of the day, she told analysts in mid-September. ( Forbes estimated her 2005 compensation at $1.43 million-well below the $4.09-million median for CEOs of food, beverage, and tobacco companies but not bad considering Sara Lee’s slumping stock price during her tenure.) But some observers wonder if robust growth is possible with a portfolio of such run-of-the-mill products. “Splitting it up makes it easier to run, but not necessarily more valuable,” says Kelly, the former general counsel.

Some fear the company will limp along for a while but ultimately could attract private equity or so-called vulture investors who streamline and then sell off the remaining assets. “It’s possible they won’t be around in five years,” says Goldin, of Technomic.

The outlook brightened slightly for the fourth quarter ended July 1st: Sara Lee reported earnings from continuing operations of 31 cents a share, exceeding analysts’ expectation of 29 cents. For the 2006 fiscal year, diluted earnings per share fell 20 percent to 72 cents, reflecting restructuring charges as well as gains from the divestitures. Sales fell 1 percent to $15.9 billion and are expected to decline to around $11.4 billion this year, reflecting the Hanes spinoff.

But the company forecasts gains in operating profits beginning in its second quarter that will end December 31st. Alexia Howard, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Company, rates Sara Lee as outperforming the market because the company will soon reap the benefits of its cost reductions and higher media spending to support its new products. If Barnes can start producing consistent improvements in operating results, the stock should start tracking upward, Howard says, but the shares won’t pick up “until people see the proof in the pudding.”

Until that happens the top job at Sara Lee can’t be much fun. As Sheli Rosenberg, Barnes’s colleague from the Chicago Network, puts it, “It’s fairly lonely for her.”