“These are people who live in America in 2021,” says Moisés Kaufman. “Except that they [also] lived here in 1863.”

Kaufman is the director of the new musical Paradise Square, set in the Manhattan slum Five Points during the Civil War era. As depicted in the show, Five Points was a community almost unimaginably ahead of its time. It comprised Black Americans — both freeborn and escaped from slavery — and Irish immigrants fleeing the Great Famine.

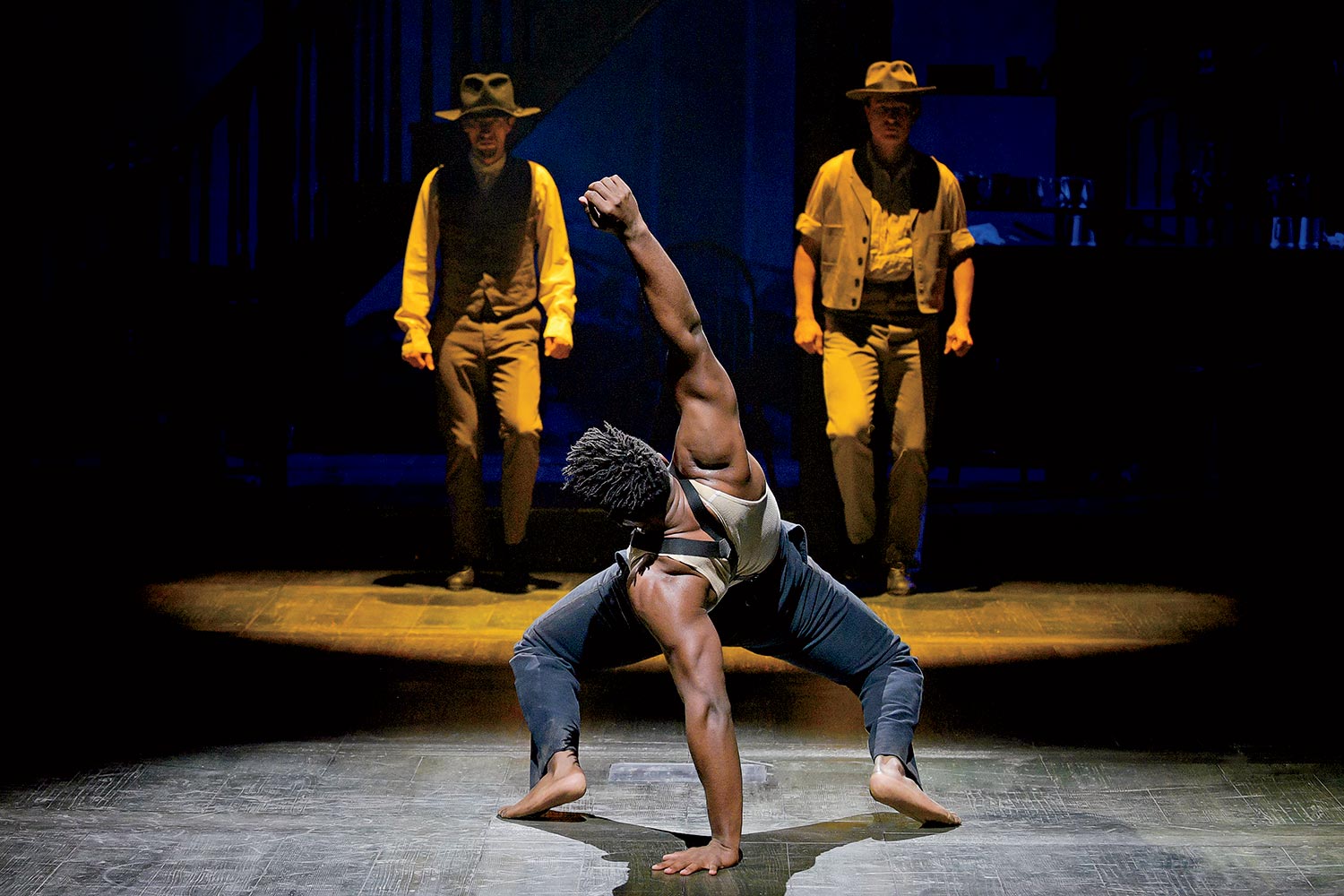

Occupying similar social strata in mid-19th-century New York, the two ethnic groups bonded. They shared music and dance — Five Points is viewed by many as the birthplace of tap dance, melding influences from Irish step dancing and African juba — and interracial marriages were not uncommon. Paradise Square tells the story of fictionalized residents of this miniature melting pot, set against the lead-up to the Draft Riots of 1863.

Playing the James M. Nederlander Theatre from November 2 to December 5, ahead of a Broadway opening in the spring, Paradise Square marks a big moment for Broadway in Chicago’s return to live performances. It’s the first pre-Broadway tryout to play downtown since The Cher Show and Tootsie in 2018, and it doesn’t come with the built-in name recognition of those properties. But it does come with an impressive creative team.

As a director, Kaufman is known for works like The Laramie Project, about the murder of Matthew Shepard, and I Am My Own Wife, a Pulitzer Prize–winning portrait of a transgender woman in Cold War East Germany. Paradise Square is his first Broadway musical, but Kaufman says the material left him “smitten” in the same way previous projects had.

“When you look at my body of work, these are plays that are always about the outsider, looking at a historical moment, and giving us a new perspective,” Kaufman says. “This fits squarely into those kinds of interests.”

The story was conceived by Larry Kirwan, the Irish-born writer and frontman of the Celtic rock band Black 47. Kirwan penned the first version using reimagined songs by the popular composer Stephen Foster, who lived his final years in Five Points.

Premiering at an Off Off Broadway venue in 2012 under the title Hard Times (taken from Foster’s “Hard Times Come Again No More”), Kirwan’s play caught the attention of a colleague of Tony-winning producer Garth Drabinsky (Fosse, Ragtime).

Drabinsky assembled a creative team to build on Kirwan’s ideas, pouring a reported $3.2 million into a 2019 production of Paradise Square at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre in California. Composer Jason Howland (Broadway’s Little Women) and lyricist Nathan Tysen (Tuck Everlasting) crafted a score that Kaufman says is now “more music inspired by Foster.”

The show also features choreography by two-time Tony Award–winner Bill T. Jones (Fela!, Spring Awakening), with contributions by 10-time Tony nominee Graciela Daniele and by cast members Jason Oremus and Garrett Coleman, both former Riverdance stars. (Unsurprisingly, Bay Area reviewers had high praise for the show’s dance sequences.)

Kirwan’s book has gone through several revisions, with the final version by Christina Anderson, whose How to Catch Creation had its world premiere at the Goodman Theatre in 2019. (Her new play, The Ripple, the Wave That Carried Me Home, opens at the Goodman in February.)

Anderson’s script centers the story on a character named Nelly Freeman, a Black woman and saloon owner whose Irish husband has gone off to join the war. “Nelly is super fierce; she’s built an amazing community around her,” Anderson says. That community, both Black and Irish, is embodied by a robust ensemble of nearly 30 actors.

“I hope that audiences find a character in the show that they can be in conversation with,” she says. “The themes that we’re wrestling with can definitely be seen in our America today.”