This is an excerpt from The Shattering: America in the 1960s by Kevin Boyle. The William Smith Mason Professor of American History at Northwestern University, Boyle is the author of the National Book Award–winning Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age.

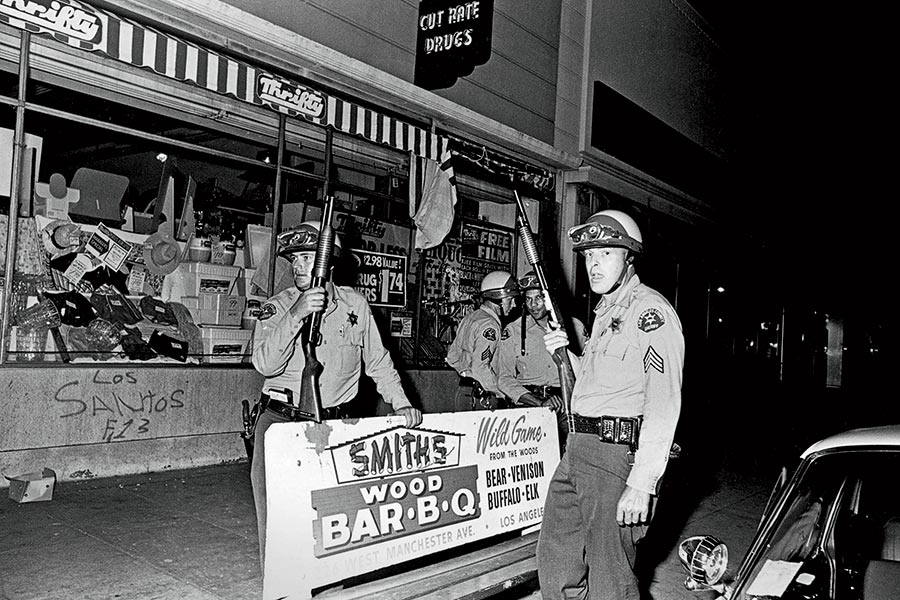

It was hard to say when things went wrong. Maybe when the patrolman pulled over a weaving Buick on Avalon Avenue, in the heart of Los Angeles’s Black neighborhood, and asked the driver, 21-year-old Marquette Frye, to walk a straight line and he offered to do it backward, playing to the crowd that had gathered round, and they laughed, which got the cop’s back up. Maybe when Frye’s mother appeared, screaming at both her son and the patrolman, and the cop arrested her too, manhandling her into the patrol car, and the laughing stopped. Maybe when Frye refused to get into the car with her and the cop hit him in the head and the jeering started. Maybe when the backups arrived, driving the motorcycles onto the sidewalk to split open the crowd, and someone picked up a rock and hurled it at the officers. Or maybe it had started decades earlier, when the authorities in every major city in the nation decided to treat African Americans as if they were a colonized people, the police their occupying army, armed with a power they’d never surrender.

After the Fryes were taken away the rage raced along Avalon, where there were buses to stone, cars to assault, and shop windows to shatter. That night — August 11, 1965 — the Los Angeles police cordoned off the surrounding eight blocks, in hopes that the unrest would play itself out, as it had in Harlem the year before. But the next day was worse, the night cataclysmic. At dusk the crowds took control of the streets across Watts, as the neighborhood was known: sweeping down its business strips, attacking the few whites who happened to be in the area, looting and torching white-owned stores, then driving off the firefighters so the blazes would burn through the night. Around 3 a.m. on August 13 the LAPD tried to reclaim the neighborhood with a massive show of force. But the crowds were larger, and more than willing to meet violence with violence. By morning more than a dozen policemen had been injured, and the streets weren’t close to clear.

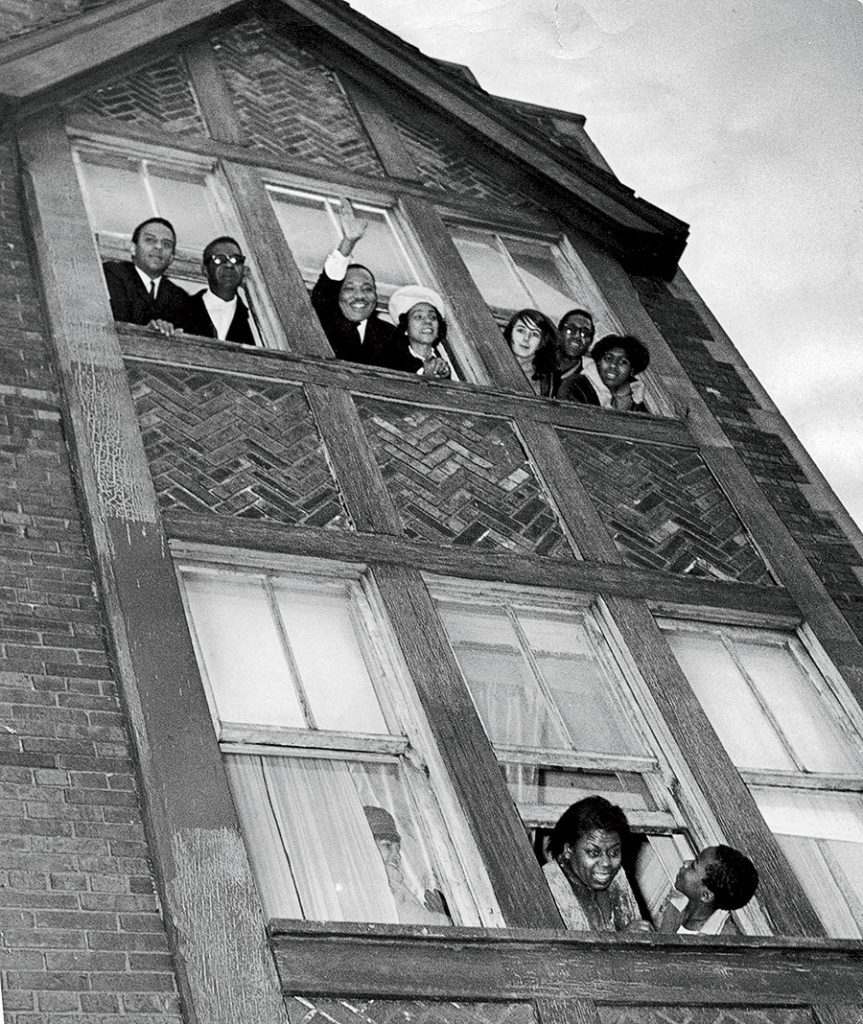

Shortly thereafter the mayor formally requested that the governor send in the National Guard. The first of 14,000 heavily armed soldiers began arriving in Watts that evening. Immediately the death toll started to rise: at least 14 African Americans were killed on the troops’ first two nights on the street, more than double the number of Americans killed in Vietnam that week. By August 17 the area had been pacified. But emotions hadn’t. In white neighborhoods people raced to buy guns amid rumors that Black mobs were going to stream across the color line, while Watts burned with talk of the fires next time. Martin Luther King Jr. heard the threats himself during a hastily arranged appearance at a Watts social center on August 18. He’d come at the request of a group of L.A. ministers, who thought his presence might calm the community. It didn’t. “All over America, the Negro must join hands … ,” he began. “And burn,” someone shouted from the crowd. King left seriously shaken, and more convinced than ever that his next step had to be out of the South. “If [we] don’t go north,” he told his aide Stanley Levison as he headed home to Atlanta, “we’re damned.”

For the balance of the month King’s advisers worked through their options. Los Angeles was too tense to manage a movement, New York too politicized, Cleveland and Philadelphia not big enough media draws. That left Chicago: three and a half million people, a quarter of them African Americans, spread among a 234-square-mile patchwork of hypersegregated neighborhoods; another three million whites in the segregated suburbs; one of the country’s most powerful politicians, Richard J. Daley, in the mayor’s office; and a vibrant civil rights campaign already in motion. On September 1, King made the official announcement. “I have faith,” he told reporters, “that Chicago could … well become the metropolis where a meaningful nonviolent movement could arouse the conscience of this nation to deal realistically with the northern ghetto.”

But faith alone wouldn’t do. King and his advisers had built their campaigns in Birmingham and Selma on a single central demand each — desegregating downtown stores, registering to vote — that they knew would trigger official resistance. In Chicago, local activists had spent the previous three years locked in a bitter battle with City Hall over the discriminatory policies of the public schools. The logical step was to follow their lead. But the autumn’s planning sessions swept right by that possibility. Obviously King would take on the schools, argued the project’s director, James Bevel, along with the segregation of housing, the high rate of unemployment, the concentration of poverty, and the injustices that ran through the welfare system. Precisely how they’d tackle such a tangle of issues wasn’t clear. Bevel was sure of the outcome, though. “We’re going to create a new city,” he told the Southern Christian Leadership Conference staff in October. “Nobody will stop us.”

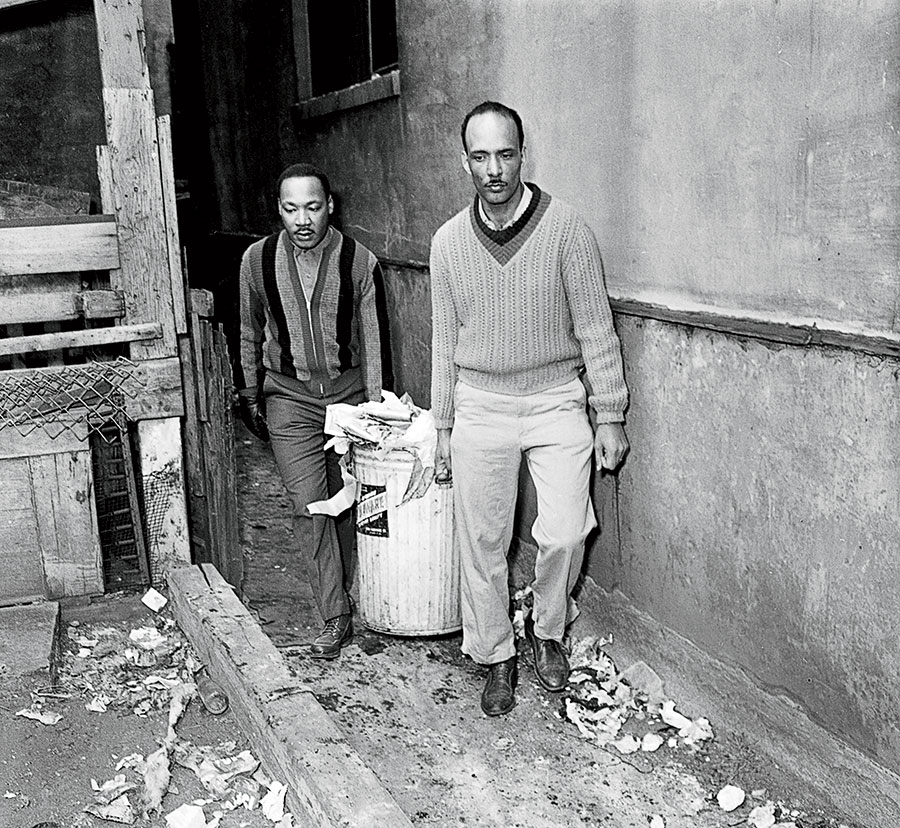

The campaign began with a perfectly choreographed move. Around the first of the year Bevel’s staffers surreptitiously rented King a $90-a-month apartment in the middle of Chicago’s West Side ghetto. On a frigid day in late January 1966 King brought a scrum of reporters through the urine-stained hallway — a consequence of the lockless front door, which permitted street-corner drunks to come in when they needed to relieve themselves — up three flights of creaking stairs, to his bare-boned new home. His first evening he opened his door to whoever wanted to stop by; for a while he sat with six members of the local gang, the Vice Lords, talking about nonviolence. The following morning he walked the neighborhood in the bitter cold, while the trailing reporters ferreted out the stories he hoped would illustrate the burdens poverty imposed.

The momentum soon faded. Part of the problem was King’s crushing schedule. He was constantly slipping out of Chicago for appearances around the country, and when he was in town he spent much of his time at events that didn’t fuel the movement: a lecture on the Black family at the University of Chicago; dinner with Mahalia Jackson; a courtesy call at Elijah Muhammad’s South Side mansion. Worse, SCLC couldn’t always read the complex dynamics that shaped urban inequality. In his first major move King led a dramatic takeover of a dilapidated apartment building near his, claiming that the tenants’ right to decent living conditions trumped the owner’s right to profit from their rents. But it turned out he wasn’t the slumlord King needed him to be; he was an 81-year-old invalid saddled with a property that didn’t cover his costs. He’d be happy to give King title to the building, he said, as long as SCLC paid the mortgage.

Nothing hurt the campaign more, though, than its breadth. With so many issues to tackle, it couldn’t focus its energies. For his part, Dick Daley wanted to make sure it stayed that way. In private the mayor was livid that King had come to Chicago. But in public he was conciliatory, even supportive. “All of us, like Dr. King, are trying to end slums,” he told the press when King moved in. “We are not perfect but we feel we have done more than any other metropolitan city in the country.” To prove his continuing commitment, he unveiled a major initiative he said would eliminate blight citywide by the end of 1967. It was a ridiculous pledge, given that 40 percent of African American housing didn’t meet minimal standards. But the point wasn’t to turn Chicago into a model city; it was to make clear that Daley was no Bull Connor. And without a Bull Connor there’d be no confrontation, no spectacular footage playing on the nightly news, no sympathy marches sweeping the country, no proof that nonviolence offered African Americans a better alternative than the rage that had swept through Watts, no way to begin building the new city Bevel had promised.

King’s advisers weren’t worried. Hadn’t Birmingham been on the brink of collapse right before its transformative moment? Hadn’t the Selma campaign stumbled toward its defining event? What was to say that Chicago wouldn’t work that way, too? “We haven’t gotten things under control,” longtime aide Andrew Young admitted in a late-winter staff meeting. “The strategy hasn’t emerged yet, but now we know what we’re dealing with and eventually we’ll come up with the answers.”

Sweet Home Chicago

One of King’s aides had suggested the idea in February 1966, less than a month after King’s arrival. But the campaign was considering so many approaches then, it was hard for one particular tactic to gain much traction. Into the mix it went, along with the proposed tenant union and the mass rally at Soldier Field and the march on City Hall, until everything started coming undone, and the staffers knew they had to do something dramatic.

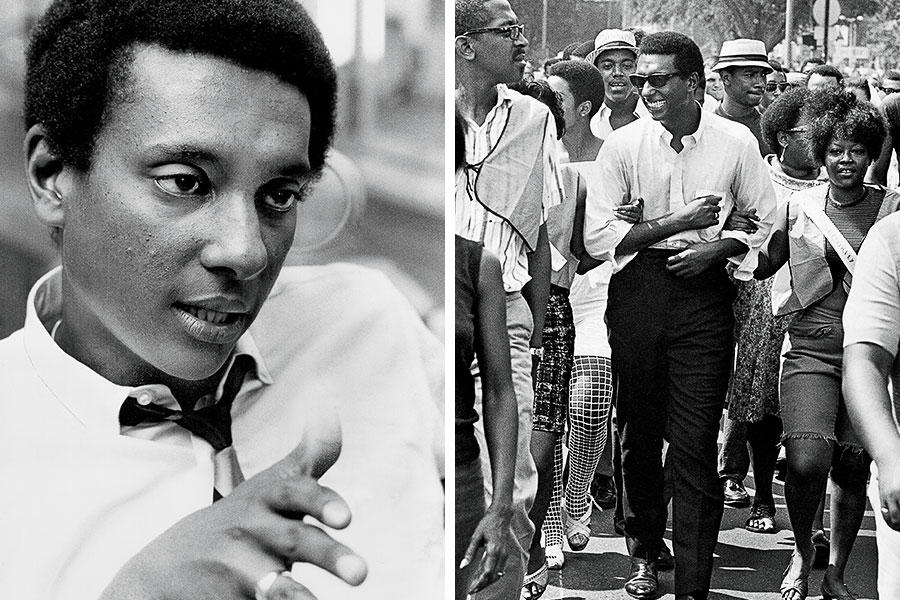

The first crisis no one saw coming. Since 1964, factions had been arguing over the direction of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Still, most of the activists who came to its annual election of officers in mid-May 1966 assumed they’d be reelecting the current chairman, John Lewis. In the first round of voting they did just that. But someone demanded another vote, and in the chaos that followed differences turned into wrenching divisions. Well into the night the factions fought it out, Lewis clinging to the group’s founding principles, his opponents insisting that the time had come to abandon dreams of the Beloved Community for the hard work of empowering Black America. In the end Lewis came toppling down, replaced by a relentlessly charismatic 24-year-old named Stokely Carmichael.

Carmichael couldn’t quite match Lewis’s extraordinary commitment to the cause. But he came close. Born in Trinidad, raised largely in Harlem, he’d first come into contact with the civil rights movement through New York’s radical circles. He’d joined SNCC as a Freedom Rider in 1961, then spent portions of three years organizing in the Mississippi Delta, the most dangerous work the movement had to offer, before becoming director of a new grassroots campaign in rural Lowndes County, Alabama, in 1965. There his signal achievement was the creation of an all-Black political party designed to give the county’s African American majority control of public affairs, its fearlessness represented by the sinewy black panther Carmichael chose as its symbol. Eleven days before the SNCC elections the Lowndes County Freedom Organization put together its first slate of candidates, a milestone Carmichael marked with a blistering declaration of independence. “We’re going to take power in Lowndes County and rule,” he declared. “We don’t even want to integrate. … Integration is a subterfuge for white supremacy.”

Then he was just another activist, drawing on the Black nationalist tradition to imagine a dramatic reworking of the Deep South’s political order. Two weeks later he was the public face of SNCC’s militant turn. The press’s take was almost universally hostile. Here was the new Malcolm X, the reports ran, the latest manifestation of the hate that hate produced. Carmichael countered with a spectacular display of defiance. He was in the middle of a highly publicized march across Mississippi in mid-June — for several days King had walked alongside him — when the local sheriff arrested him for lack of a permit. He spent the afternoon in jail, made bail, and was back with the march in time for its evening rally. About 600 people were waiting for him. “This is the 27th time I’ve been arrested, and I ain’t going to jail no more!” he shouted from the makeshift stage. “What we gonna start saying now is ‘Black Power.’ ”

“Black Power!” the crowd roared back.

“That’s right,” he replied. “That’s what we want, Black Power. We don’t have to be ashamed of it. … We have begged the president. We’ve begged the federal government — that’s all we’ve been doing, begging and begging. It’s time we stand up and take over. Every courthouse in Mississippi ought to be burned down tomorrow to get rid of the dirt and the mess. From now on, when they ask you what you want, you know what to tell ’em. What do you want?”

“Black Power!” they shouted again and again and again.

The firestorm started the following morning. Sparked by the New York Times’s front-page story on the previous evening’s rally, it leaped from paper to paper, magazine to magazine, onto the nightly news, and into national politics; the outrage intensifying with each repetition of Carmichael’s incendiary phrase. This was more than militancy, opinion makers insisted. It was the poisonous politics of extremists “inching dangerously toward a philosophy of black separatism … almost indistinguishable from the wild-eyed doctrines of the Black Muslims and heavy with intimations of racial hatred,” as Time magazine put it in its blistering story. “In this context the Gandhian concept of nonviolence espoused by Martin Luther King is in danger of crumbling.”

At first King’s advisers weren’t sure how to respond. They tried quiet diplomacy, hoping that Carmichael might be reined in by a well-placed word. They tried carefully constructed public statements meant to reassure whites that Black Power was an aberration, a reflection of frustration rather than a wholesale rejection of integration. They even tried moral condemnation, the most powerful rhetorical weapon King could wield. None of it worked. By the end of June, Black Power had swept from SNCC to Congress of Racial Equality, whose chairman dismissed nonviolence as “a dying philosophy,” a striking turn for an organization founded by radical pacifists. The NAACP’s director, Roy Wilkins, replied with the flat of his hand. Black Power is “a reverse Mississippi,” he said, “a reverse Hitler, a reverse Ku Klux Klan. … We of the NAACP will have none of this.”

That’s when King’s analysis sharpened, just as the movement seemed to be breaking apart. Sharp words weren’t enough, he told the Times on July 9. Black Power’s militancy had to be met with “militant nonviolence,” acts of civil disobedience “extreme enough to stop the flow of a city.” Precisely what those acts might be he couldn’t yet say. But whatever the tactic, the campaign wouldn’t stop until local, state, and federal authorities had taken vigorous action against the structures that sustained the ghettos. Anything less wouldn’t do, not if the nation wanted to defuse the anger on which Black Power rested. “Now people have to understand the choice is no longer between nice little meetings or nonviolence,” he insisted. “It is between militant nonviolence and riots.”

Two days later the violence came home. It started with a tussle over a fire hydrant in a poor Black neighborhood a mile or so west of downtown Chicago: cops on one side, kids on another, both sides’ emotions frayed by the heat. By the time King stumbled onto the conflict while driving to the evening’s mass meeting, there were six kids in jail and angry crowds in the street. He spent the rest of the night trying to defuse the situation with talk of meaningful reform peacefully secured, mostly from the sweltering sanctuary of the local Baptist church. But a portion of the people he’d drawn to his impromptu rally walked out on him, while others laughed at his naivete. And when the reporters left to file their stories around midnight, they had to be escorted out of the church under armed guard.

The crowds came out again the next night, ripping through the neighborhood shopping strip, smashing windows, looting stores, pelting the cops with bricks and stones when they tried to intervene. On the third night, the police brought out the heavy weapons — shotguns, machine guns, and thousands of rounds of ammunition — so they could reclaim the streets. Instead, the violence surged along the ghetto’s sinews: north to the projects, where the cops engaged in an hourlong battle with snipers, and three miles west into the area where SCLC had rooted itself six months before. King spent the evening driving the neighborhood with Andrew Young, pleading for peace. But no one was listening. In the course of the night dozens of people were injured, two killed. One was a 28-year-old man gunned down while looting, the other a 14-year-old girl hit by a random shot while walking with friends three blocks from King’s apartment.

King came home to an early-morning strategy session, a first attempt to shape the response he had to make. Through the next day the discussions ran, as the governor flooded the West Side with a hundred truckloads of National Guardsmen, whose presence reduced the night’s troubles to a sprinkling of incidents. The planning continued through the tense weekend that followed, when everyone feared that the violence would flare again, and into the following week, when there was more and more talk of the Chicago campaign’s failures. Gradually the focus tightened on to a single dramatic tactic. At the end of July, King said, SCLC would launch a series of marches into white neighborhoods on the city’s far West Side. The demonstrations would target realtors who refused to serve African Americans looking for homes, the front line in a series of barriers sustaining the urban color line. But confronting realtors wasn’t really the point. By marching into the bungalow belt the movement would seize up the city, just as King had said it would.

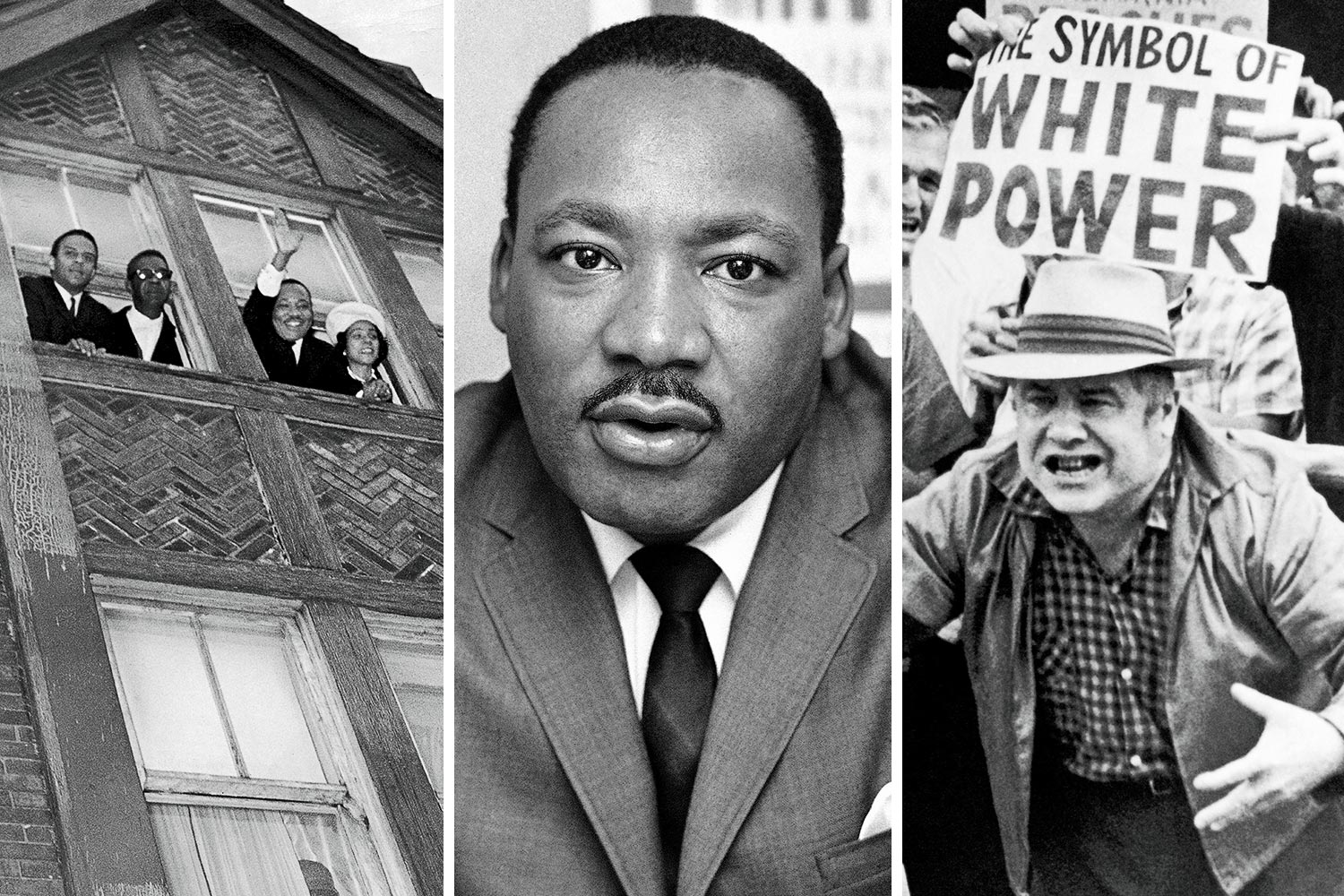

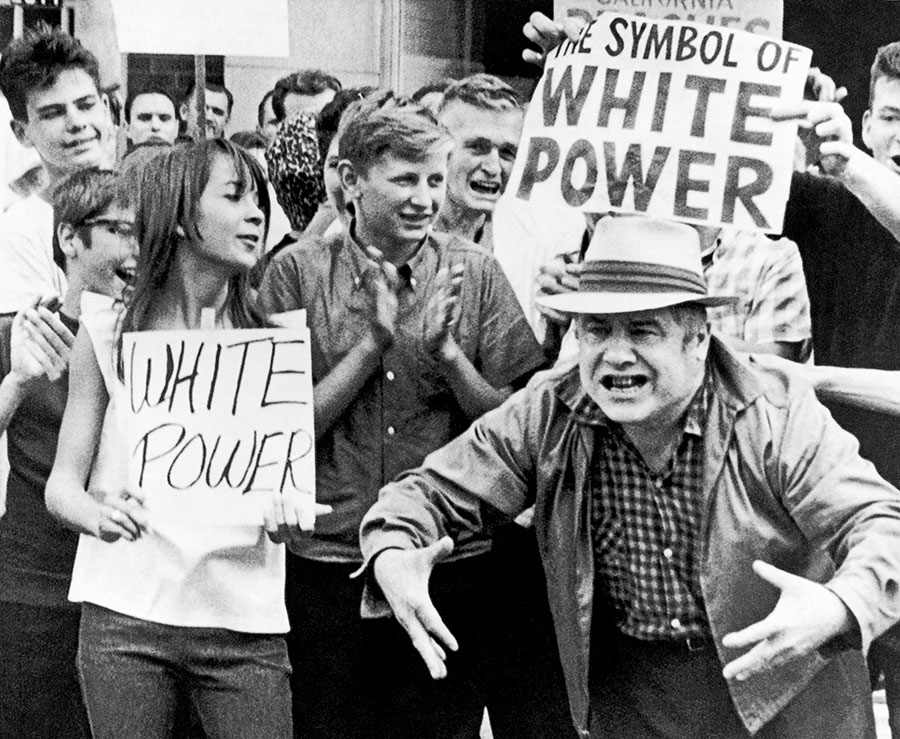

King was in Atlanta when 250 protesters headed into the Gage Park neighborhood, due west of Chicago’s sprawling South Side ghetto, on Saturday morning, July 30. They marched almost three miles — along a business strip and through a large public park — without any trouble. From there it was only four blocks to the realty office they planned to picket. But the way was mobbed with some 400 whites. At first they settled for booing and jeering and the occasional chant of “white power” from behind the thin line the police had established in the middle of the street. Then the protesters reached the realtor’s shuttered storefront, and the whites started throwing rocks and bottles. Both of the march’s leaders were hit, one of them knocked to the ground. With the march broken by the violence, the protesters rushed out of Gage Park under police protection.

On Sunday afternoon they returned. This time they came prepared for trouble: instead of walking into the neighborhood they drove in a 70-car caravan to the public park, so they’d only have four blocks to march. But there were even more whites waiting for them than there had been the day before: upward of 3,000, the police said later, though the streets were so packed no one could know for sure. Into the thick of them the marchers moved, surrounded by cops in riot gear, as the chants grew louder — “Burn them like Jews!” some shouted — and the rocks and bottles came raining down again, now with beer cans and cherry bombs scattered in. Down went a 22-year-old patrolman, his hand cut open by shattering glass; a 57-year-old minister struck in the face with a brick; a middle-aged nun, blood soaking through her habit. Still the line kept moving. Twice the cops had to break blockades the mob set up in the protesters’ path. But they couldn’t — or wouldn’t — stop the whites who swarmed into the park as soon as the marchers had cleared it, surged around the cars they’d left behind, and set two dozen of them on fire. In the end 45 protesters were rushed to the local emergency room. Most of the rest had to slog back to the ghetto on foot. When they reached the color line a knot of supporters was waiting for them, singing “We Shall Overcome.”

Suddenly SCLC had the confrontation the Chicago campaign had been missing: peaceful protesters on one side, rabid racists on the other, with the resulting bloodshed splashed across the nation’s front pages. But a weekend wasn’t enough. On Tuesday and Wednesday, August 2 and 3, organizers sent marchers into the Northwest Side. Again massive white mobs filled the streets, shouting the same vicious taunts and slogans, but they stopped short of the South Side’s violence. So the movement swung the protests back to Gage Park. The next march would be on Friday, August 5, King announced. It would follow the same route as the previous Sunday, with one critical addition. He would lead it.

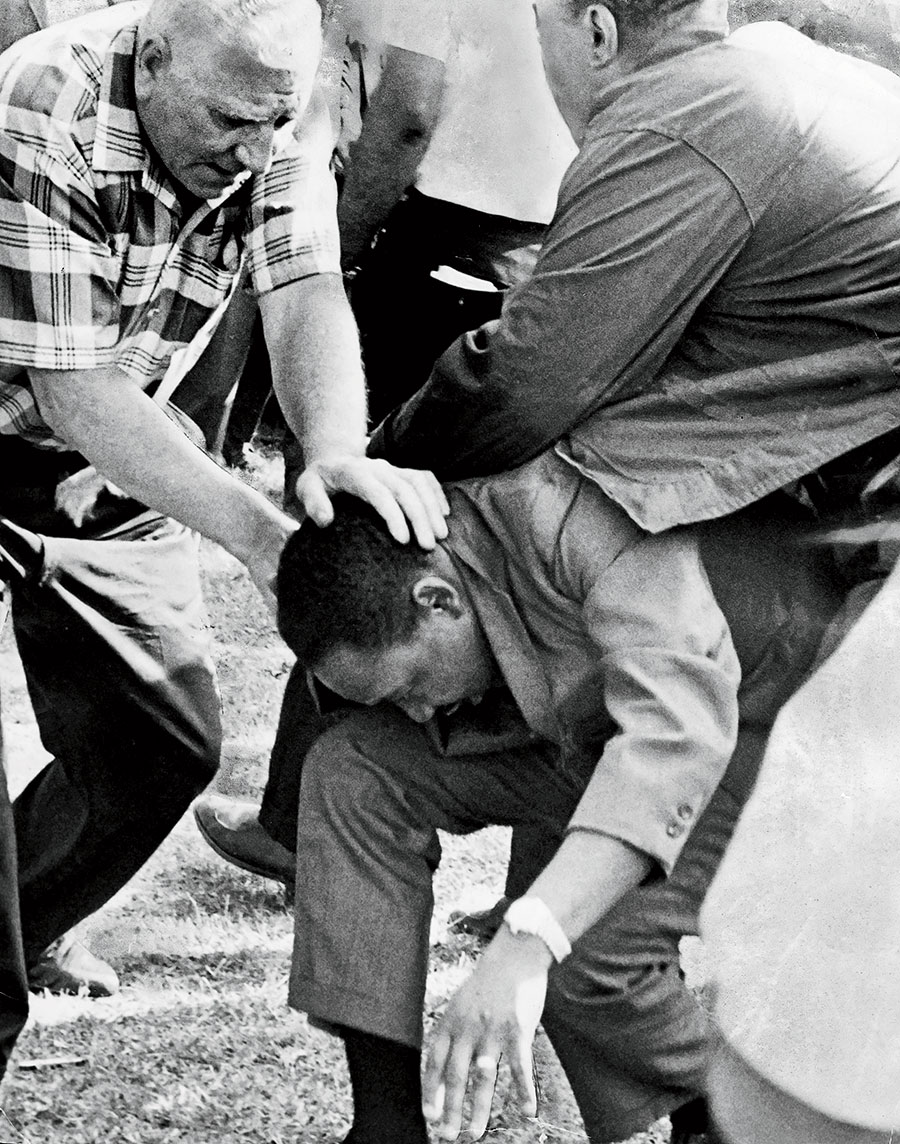

There were already thousands of whites in the park when King arrived late that afternoon. As soon as they saw him getting out of his car they started chanting, “Kill the n——! Kill the n——!” and “We Want Martin Luther Coon!” Then the debris arced over the police lines — more rocks and bottles and cherry bombs — and something hit him above the base of his neck, a blow hard enough he stumbled a step and fell to one knee. There he stayed for a moment or two, the nation’s Nobel laureate with his head bowed down and his hand splayed out on the trampled grass, until he felt strong enough to get back on his feet and march into the mob he’d come to save from itself. “I have never in my life seen such hatred,” he declared at the protest’s end. “Not in Mississippi or Alabama. This is a terrible thing.”

There were more marches over the weekend, more mobs, more violence, North Side and South Side both, the ugliness now set against the news of King’s stoning, which rocketed around the world. In the chaos, at least one of his aides could see the spirit of Selma descending. So he took that campaign’s pivotal decision and brought it up to Chicago. “I have counted up the costs,” Jesse Jackson proclaimed at a Monday night rally. “My life. Bevel’s life. Even Dr. King’s life. Over and against the generation and the continuation of a kind of sin that’s going to internally disrupt this country and possibly the world. I have counted the cost! I’m going to Cicero!”

In form and function it was pure imitation, a mimicking of the recklessly brilliant move Bevel had made after the first burst of violence in Selma, when he announced that the movement would march to Montgomery, a 50-mile trek across Klan country. Now Jackson had announced that protesters would march into Chicago’s most notoriously racist suburb while the cops who’d surrounded them in Gage Park stood on the other side of the city line, prevented by law and reason from following along. There’d be massive mobs waiting, just as there had been in 1951, when a single Black family’s arrival at their newly rented apartment had triggered rioting so severe the governor had had to call out the National Guard. In the years since, the hatred had shown no signs of abating: only three months earlier four white teenagers had bludgeoned a Black 17-year-old to death with a baseball bat simply because he’d been walking down the street alone. The Cook County sheriff matched Jackson’s counting with his own calculation. If the movement marched into Cicero, he told reporters, someone was going to be killed.

That possibility City Hall couldn’t abide. Since the marches had started, Dick Daley had offered the movement nothing beyond police protection. Less than a day after Jackson’s announcement he called in the press to say that while he fully supported the right to protest, it would be far better to negotiate a solution to the movement’s demands. He’d already arranged for some of Chicago’s most influential men to meet the following week. He sincerely hoped that King and his aides would come too, along with representatives of the city’s realtors, so that they could all sit and reason together. In the meantime SCLC ought to hold off on its Cicero march, so as not to put lives at risk when discussions would do. Surely Dr. King could see the logic of that.

He could. In every campaign he’d waged, there had come a point when the pressure became too great for the authorities to bear. The Montgomery buses running empty. Kids in the streets of Birmingham. A line of marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. That’s when the breakthroughs came: when the powerful couldn’t withstand the powerless anymore. For the balance of the week the movement staged some of its largest protests yet around Chicago, though none near Cicero, in a final push before the negotiations began, while King’s closest advisers hammered out a list of demands meant to open up the city’s housing market. On Wednesday morning, August 17 — 18 days after the first cataclysmic march into Gage Park — they walked into the suitably neutral ground of the Episcopal diocese’s elegant cathedral house and took their seats among the bankers, industrialists, labor leaders, and clergymen the mayor had handpicked to attend.

There were some preliminaries, the predictable posturing of powerful men in each other’s company. Then one of King’s aides presented the movement’s demands. Would the marches end if these demands were met? Daley asked.

Yes, King replied. Was the mayor ready to do so?

Daley picked up the sheet the aide handed to him, read it aloud so everyone in the room could hear the terms again, and said that he was.

It took only a moment for King’s circle to realize what had happened. Daley had given them everything — and nothing at all: no guarantees, no timetables, not a single assurance beyond his word that he would fulfill the promises he’d just made. As they started to press him on implementation, though, the realtors’ representatives cut in to say that they couldn’t go along with the mayor’s appeasement of the protesters. Immediately the conversation swung around to the realtors’ intransigence. Through the rest of the morning session the pressure built, not only from Daley but also from the clergymen and businessmen he’d brought in to back him, the weight of consensus crushing down until the realtors finally buckled. The meeting’s chair, the president of a major railroad line, gave them some time to caucus. When they returned they put on the table two concessions that dovetailed with Daley’s: they’d publicly support the principle of neighborhood integration, they said, and they’d urge their members not to discriminate against African American customers. “This is nothing,” King hissed to a colleague. But the chair pointed out that both the mayor and the realtors had now accepted the demands King had presented, so there were no grounds for continued demonstrations. And the trap Daley had set snapped shut.

They staved off defeat for a week, first by insisting that a subcommittee draw up the details of a settlement, then by reviving the threat of Cicero. But the threat had been hollowed out: SCLC couldn’t possibly mount the march, not when any one of 50 prominent Chicagoans could say to the press that SCLC was inviting horrific violence in pursuit of goals it had already won. On Thursday, August 25, the subcommittee finalized a 10-point accord that codified the pledges made at the previous week’s meeting. On Friday King signed it.

At the subsequent news conference he gave the deal a furious spin. “The total eradication of housing discrimination has been made possible,” he said. “Never before has such a far-reaching move been made.” But anyone who read the accord knew better. After six months of organizing and a month of marches, after the bricks and bottles and howling mobs, the movement had come away with a set of paper promises. That evening King led his campaign’s final, tepid rally. In the morning he flew home to Atlanta, leaving behind a color line he hadn’t been able to break, a system of segregation and domination he couldn’t destroy, a city he couldn’t transform, and festering wounds he had failed to salve.

The Unheard

In the autumn of 1966 Stokely Carmichael seemed to be everywhere. He appeared in the rarefied pages of the New York Review of Books to explain Black Power to the intelligentsia, on NBC’s Meet the Press to reach the nation’s power brokers, and in front of Harlem’s PS 201 to support local demands for community control of the city’s schools. He lectured to 10,000 students at Berkeley, though the Republican candidate for governor, Ronald Reagan, asked him to stay away, and to an overflow crowd at Yale. He crisscrossed the country — from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco, Oakland to Detroit — to meet with Black activists; packed church halls in Columbus and Dayton, a lyceum in Boston, and a public park in Watts for a rally the city refused to sanction. In almost every venue he delivered a message of uncompromising militancy. “We are tired of trying to explain to white people that we’re not going to hurt them,” he told the crowd at Berkeley. “We are concerned with getting the things we want, the things that we have to have to be able to function. … The question is, will white people overcome their racism and allow for that to happen in this country? If that does not happen, brothers and sisters, we have no choice but to say very clearly, ‘Move over, or we’re going to move over you.’ ” Twice he was arrested for inciting riots.

Most African Americans weren’t impressed. Only 18 percent of those polled in December 1966 thought Carmichael was helping to advance civil rights, a figure that placed him at the bottom of a long list of Black activists, barely above Elijah Muhammad. For a portion of the African American Left, though, Carmichael’s politics were electrifying. By the end of the year cadres of young radicals in New York, Newark, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles had created political parties inspired by his Lowndes County campaign, as had two San Francisco–area militants, 24-year-old Huey Newton and 30-year-old Bobby Seale, who in October launched the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, across the bay from the Haight.

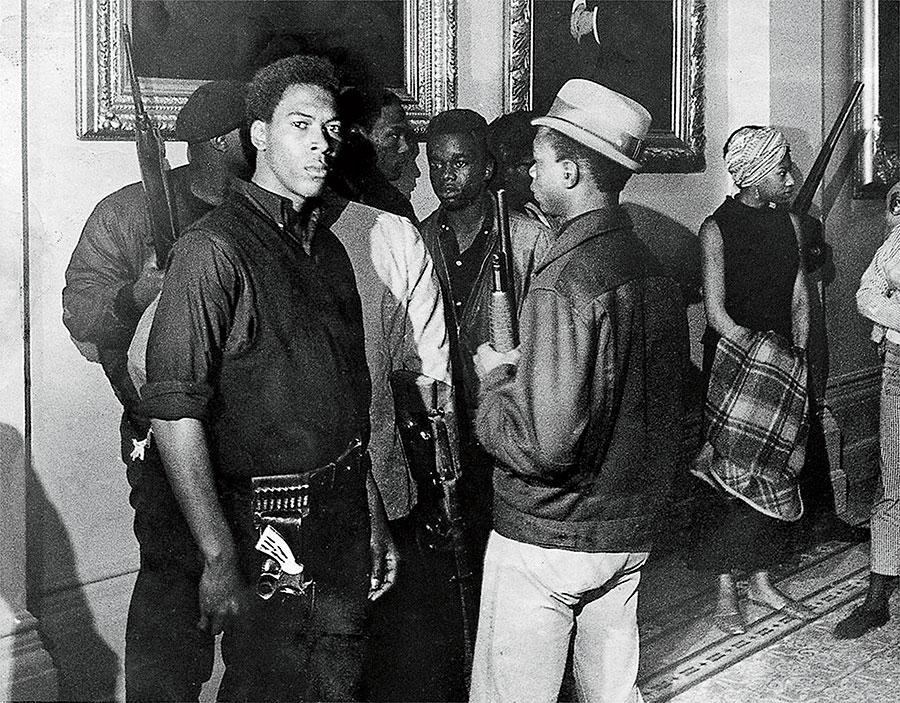

Beyond a few friends and colleagues, the party had no members. So Newton and Seale set to organizing, drawing not on the SNCC style of grassroots mobilization that had inspired Carmichael but on the power of self-presentation. They pieced together a uniform that combined an urban look of black pants, a crisp blue shirt, and a black leather jacket with the black beret favored by Latin American revolutionaries. Then they assembled a cache of weapons, loaded them into their cars, and established neighborhood patrols meant to protect Oakland’s African Americans from the city’s overwhelmingly white police force, an act of bravado made possible by a loophole in California law that allowed citizens to carry loaded guns as long as they weren’t concealed. The inevitable confrontations with rattled cops brought in a fistful of recruits and a good deal of admiration. But the Panthers didn’t have their breakthrough until the state assemblyman from Oakland’s white suburbs introduced a bill to close the loophole. On May 2, 1967, Seale led 29 of his heavily armed comrades — three-quarters of the Panthers’ membership — into the state capitol to express their opposition to the move. As a lobbying tactic it left something to be desired. As guerrilla theater it was superb. The next day, news of the Panthers’ “invasion” ran in newspapers across the country, usually alongside a photo of young Black Che Guevaras standing in Sacramento’s marble halls with rifles slung over their shoulders, Black Power’s revolutionary vanguard revealed.

A month later urban America’s racial wounds split open. On June 2, a police assault on a peaceful demonstration at a Boston welfare office sparked three nights of looting and burning in Roxbury. Tampa’s Black neighborhood erupted on June 11, when a policeman shot and killed a 19-year-old he said had robbed a camera store; Cincinnati’s on the 12th, following a street-corner arrest gone wrong; and Buffalo’s at the end of the month with another three nights of rioting, this time triggered by the police wading into a fight at a public housing project. After Buffalo there was a two-week lull. Then, on the evening of July 12, 1967, two white patrolmen stopped an African American cabbie for a routine traffic violation in Newark’s Central Ward. Words were exchanged, the cabbie arrested. On the way to the precinct house the cops beat him up. As the news spread, people said the cabbie was dead.

Newark’s agony began exactly as Harlem’s had in the summer of 1964 — with an impromptu rally in front of the local police station that the police decided to break up by wading into the crowd with nightsticks raised — but it spun out with the fury of Watts. The first night the rioting was localized. On the second night the mobs grew so large the police couldn’t contain them. From the Central Ward the looting spread to downtown. Almost a hundred stripped stores were set ablaze, the fire crews pelted with bricks and bottles. And the cops on the street were reporting sporadic sniper fire coming from tenement rooftops. Early in the morning the mayor asked the governor to send in the National Guard, civil order having broken down.

The governor responded with 3,000 troops and a swaggering promise that “the line between the jungle and the law might as well be drawn here as well as any place in America.” But the guardsmen weren’t law-enforcement officers. They were weekend soldiers thrust into what city officials thought was an “open rebellion.” The first firefight came around 6 p.m. on the third day, a fierce exchange that began when a policeman was hit by a shot fired from the top floors of a housing project. For the next 48 hours the troopers turned central Newark into a war zone, suppressing the looting with mass arrests and increasingly undisciplined violence and the rooftop attacks with their own raking fire. Resistance finally collapsed on July 17. By then 1,500 people had been arrested, 725 injured, and 26 killed, the youngest just 10 years old.

Days later, in the early morning of July 23, the Detroit police raided an after-hours bar in a poor Black section of the city’s West Side. In their rush to finish the operation the cops got rough with some of their prisoners, pushing and shoving and wielding their batons. A few onlookers started tossing insults at the officers, followed by bottles and stones. On the edge of the crowd a teenager launched a trashcan through the window of Hardy’s Drug Store, while someone else set a shoe shop ablaze. And it all started again.

This time the unrest moved with startling speed. Within half a day the looting had spread to the West Side’s two major arteries, dozens of storefronts were burning, and sniper fire had begun. On Sunday afternoon the governor sent in the National Guard. But Detroit was a sprawling city, six times the size of Newark, and by evening there were outbreaks in neighborhoods so far apart they couldn’t conceivably be contained, even by troops with the training the guardsmen didn’t have. The night was horrific, the next day no better. By late Monday 19 people had been killed, 800 injured, and hundreds more made homeless by the fires that were raging out of control. With reports pouring in of disturbances flaring in half a dozen smaller cities across the region, everyone knew there was worse to come.

Lyndon Johnson hated the thought of federal intervention. He could see the terrible image of combat troops fighting on the streets of Detroit, the horrifying possibility of a Black child killed by a white soldier he’d deployed, his administration’s commitment to racial change and the eradication of poverty destroyed by his unleashing of state-sanctioned violence. When the governor’s request arrived midday Monday, LBJ agreed only to send the soldiers to bases outside Detroit. There they sat through the evening, one brigade from the 82nd Airborne, another from the 101st — 5,000 men in total — as the mayor and governor pleaded with the White House to use them. Johnson waited until 11 p.m. to issue the order. Even then he seemed desperate to distance himself from what he had done. “I am sure that the American people will realize that I take this action with the greatest regret,” he said in an anguished midnight television address. “Pillage, looting, murder, and arson have nothing to do with civil rights. They are criminal conduct. And the federal government in the circumstances here presented has no alternative but to respond.” Shortly thereafter armored personnel carriers rumbled into the East Side, the first time in a quarter century federal troops had been dispatched to crush an uprising in an American city.

Crush it they did. But it took three bloody days. When the city was finally brought under control, on July 28, the death toll had reached 43, and the number of injured had climbed to 1,200. Three-quarters of those killed were African American, among them three men executed by a contingent of cops during a raid on a seedy hotel on the upheaval’s fourth night. In the five days of the rebellion 7,200 people had been arrested, 2,500 stores looted, 412 buildings burned, $50 million in property lost. Not since an anti-Black pogrom ripped through Tulsa in 1921 had an American city suffered such devastation.

Stokely Carmichael promised more. He was in Havana when Detroit exploded, attending an international conference of revolutionary movements. “We are moving to guerrilla warfare within the United States, since there is no other way to obtain our homes, our land, our rights,” he told a packed news conference. “They have taught us to kill. Now the struggle is in the streets of the United States.” The vast majority of African Americans who lived in Detroit’s riot-torn neighborhoods didn’t agree. Only 3 percent thought that people had taken to the streets in pursuit of self-determination, according to surveys conducted shortly after the uprising ended, whereas 60 percent thought they’d come out to protest the police brutality, poor housing, unemployment, and poverty that afflicted their communities. Violence wasn’t the answer, said 81 percent of those surveyed.

Yet violence there had been, just as Martin Luther King had feared there would be if the urban poor couldn’t secure meaningful reform any other way. He’d tried: the evenings he’d spent in his ghetto apartment talking with gang members; the day his advisers had claimed control of a tenement on behalf of the people who lived there; the nights he’d driven through West Side Chicago pleading for peace; the afternoon he’d marched through the mobs in Gage Park. Now it had come to this. Not guerrilla warfare, though there were flashes of that. Not Black Power, though it had its adherents. But the enraged voice of the dispossessed, demanding to be heard.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Boyle. Used by permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company Inc. All rights reserved.