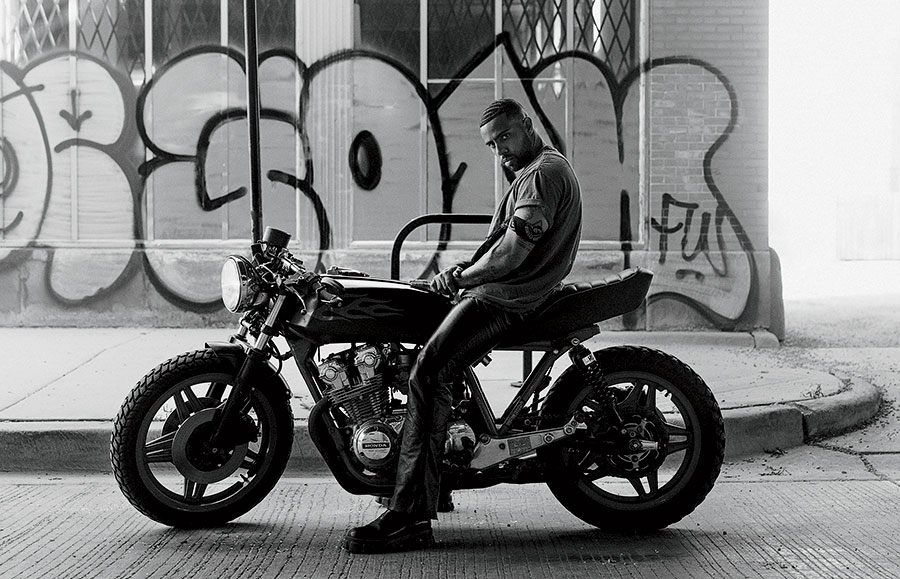

Vic Mensa is in the house. Or, more precisely, a converted three-story brick storefront in West Town that is home to the record label At the Studio. The 29-year-old rapper has just arrived on his vintage black-and-red Honda motorcycle, and he’s dressed to ride: black leather pants, black boots, and a denim vest that shows off his jacked and inked arms. The left side of his head is tattooed with the phrase “Where Is My Mind,” visible through his closely cropped hair, and “Southside” stretches across his throat.

From the outside, the Milwaukee Avenue building looks abandoned — a rusted front door, no signage, covered street-level windows — but inside, the vibe is livelier. There’s someone behind a large mixing board, and others are scattered around doing whatever people do at recording studios. The scent of weed is pervasive.

Mensa settles into a third-floor room that has been his haven since he moved back home to Chicago from Los Angeles two years ago. This is where he comes to write, usually during what he calls his “most alert hours,” from noon to 6, when the sunlight streams in — a switch-up from his previous night-owl schedule. The room has a couple of cushy old chairs, a desk with two small speakers and a chair, and not much else. That spartan aesthetic — and turning off his phone — helps Mensa focus. That hasn’t always been easy.

Born Victor Kwesi Mensah and raised in Hyde Park by a Ghanaian economics professor father and a white American artist mother, the Whitney M. Young Magnet High School graduate gained cred in underground hip-hop circles early on for his mixtapes, which featured intricate wordplay and eclectic sounds. He broke through to the mainstream when Jay-Z’s Roc Nation label signed him in 2015. Kanye West soon made him a protégé, and the two collaborated on several tracks. (Mensa earned a Grammy nomination for cowriting West’s “All Day.”) His debut full-length album, 2017’s The Autobiography, reached No. 9 on Billboard’s digital chart.

But as his career was ascending, his life was descending. He struggled with mental health and drug addiction and had run-ins with the law. In 2017, he was arrested in Beverly Hills for carrying a concealed weapon. (He got probation.) More recently, in January, he was arrested at Washington’s Dulles International Airport after returning from Ghana with a stash of shrooms and other hallucinogenic drugs. (He received a one-year suspended sentence.)

These days, Mensa is on a much different path. He is sober, he says, has found solace in meditation and a new religion, and is determined to stop being his own worst enemy. He’s also working on his second studio album, a sonically upbeat departure from his last one, which he hopes to release by year’s end. But music isn’t his only venture. This summer, he curated an art exhibition at Kavi Gupta Gallery called Skin + Masks. Mensa has described the show as an expression of “identity and experience that transcend the proximity to the white gaze.” And he recently launched his own cannabis line, 93 Boyz, which he claims is the city’s first Black-owned brand. It will help fund Save Money Save Life, his nonprofit that aims to uplift people of color in Chicago and elsewhere, largely through the arts.

Leaning back on the squeaky desk chair, feet propped on a nearby windowsill, Mensa talks with candor about where he’s been, where he’s going, and what he’s learned along the way.

■ I caught a real blessing about a year ago that I won’t fully detail because it was a combination of many illegal things, but it involved drugs, guns, alcohol. There was gonna be no talking my way out of this one because it was just some real stupid shit and all bad. I was going through so much at the time. I had some people trying to kill me, and I was struggling financially and creatively. I was just like, Look, God, if you could get me through this period of time, I’m gonna change. That was my first time honestly coming to God. I went to church as a kid, but I didn’t really believe in it. So I found myself in this extremely messy situation, and by the grace of God, friends came and took care of me and got it all squared away, and I didn’t have to pay the ultimate price. I didn’t have to go to prison. I didn’t get hurt. I wasn’t plastered across every TV station on the planet. And I just decided, Man, I’m done with this shit, and I stopped everything. I stopped smoking, stopped drinking, stopped doing drugs. I stopped messing with a bunch of different women. I even stopped small things like stealing from the grocery store at the sales checkout.

■ In the scripture it says, “Do not despise the day of small things.” I realized that all those things factored into the totality of my well-being. When I started to acknowledge the blessings I’ve been given, I had to ask myself, Why am I doing things every day that are actively and purposefully shortening my life? I didn’t care about my life before. Now I’m grateful for not being incarcerated or dead. Because I’ve done a lot of things and been through a lot of shit that many people don’t survive or get to walk free after.

■ I’ve never been a one-dimensional person, so even though I may have had my intense fits of egotistical behavior and volatility, I’ve also always been an empathetic, generous, kind person. It’s the Gemini thing. What I’ve realized is that the process of growth is to not be beholden to the inclinations of my nature, which can be explosively polar. Growth has been learning how to integrate the parts of my personality so that I’m not this Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde.

■ The majority of my life has been existing in some state of depression, in one way or another. I have a song called “2Honest,” where I speak about how I found this notebook in my mom’s house. It was from first grade or kindergarten. There’s a bunch of cute doodles, and on the front it’s got a sticky note that says, “No girls allowed.” I’m flipping through it and I get to a place where “I hate myself, I hate myself, I hate myself” is written across the whole page. And the next page has an image of a stick figure with a sword through its neck. And I’m like, Oh man. I had a lot of empathy for myself in that moment, because I recognized that the things I’ve been dealing with in my teenage and adult years were not new and I’ve survived those.

“I’m grateful for not being incarcerated or dead. because I’ve done a lot of things and been through a lot of shit that many people don’t survive.”

■ When I was 22, I didn’t think I would live to 23. I was caught up on that. I put it in my music. I made so much of that same “I’m depressed, I’m drug-addicted” suicidal music. I’d be talking about how I wanna get into the 27 Club [of artists who died at age 27]. And now I recognize that the words we say have enormous power to shape the world we look at and touch and feel. Especially in music, because music is this potent spiritual form of communication. Finding a real sense of peace is only strengthening my creativity and prolonging my possibilities. Now I see myself with a long timeline.

■ We’re pumped so full of fear. John Lennon has a line on Plastic Ono Band about how you get to 18 or 20 and they expect you to pick a career, but you can’t even function, you’re so full of fear. And it’s so true. It’s like we exist in this vacuum of fear and propaganda. We fear each other as Black people. We fear ourselves. We fear the police. We fear oppression. We fear violence. White people fear Black people, but they also fear the consequences of their forefathers’ [actions]. We fear losing our house. There are so many forms of fear that we’re injected with. And that’s just from birth. I believe a lot of the things I’ve carried predate my existence. Generational trauma.

■ I’ve done a lot of psychedelic spirit medicine, like ayahuasca, at a lot of ceremonies. There’s also MeO-DMT, this toad secretion that give you some deep revelations. The first time I did ayahuasca, I was in a super-dark place. It was right before I did The Autobiography. I went into it asking, “Why do I feel so much pain?” And at one point in the ceremony, I felt as if I was seeing through my 5-year-old eyes. I was seeing my mother’s blond hair, and then this higher voice said I used to want blue eyes, that is the root of my pain. That gave me a lot of perspective.

■ Once I became a preteen, I started to internalize the way that teachers treated me differently. I felt that from my earliest experiences in school, when I was put in a developmentally challenged class with kids who had disabilities and were in wheelchairs. When the police [mistreatment of Black people] aspect was added into it, that’s when I started to really overcompensate, like, OK, fuck the world. Yes, I am stealing. Yes, I am ultraviolent. And fuck what anybody has to say about it.

■ When I was 11, this guy named Dare took me under his wing as a graffiti writer. He’s the person I wrote the song “Heaven on Earth” about. This was before I ever rapped. He was like, “Man, this is my shorty. This is my little bro. He’s dope.” And he put me in his jam crew. So I had all these big brothers that were basically my age now. They were tremendous influences because they supported me and gave me a vote of confidence. They were like, “You’re creative, you’re fresh.”

■ I had an entirely nurturing experience in the home. But the thing about the South Side, depending on your nature, certain things are unavoidable. And I was always a kid who liked to get into shit. So if I stepped outside of my home, I was instantly in a danger zone. You don’t have to look for it. Even in Hyde Park. It’s like this oasis surrounded by very violent neighborhoods. Niggas still get killed on the corner.

■ At the time I wrote “16 Shots” [about Laquan McDonald], I reveled in my hatred for the police. And it was a completely valid response to what has always been the condition of the Black person in America: a target of police murder. Ever since I was a kid, every time I’d see a cop, I would think, I would kill his ass if I could get away with it. I had to realize that by feeding into that carnal fear and desire, I’d allowed the distortion of their humanity to, in turn, distort mine. I understand now that seething in anger and hatred towards anyone or anything is more damaging for me. I’m robbing myself of my peace and my power. So I don’t hate the police, because I don’t have the space to hate them. Do I disagree with their function and existence? A thousand percent. I believe in the disbanding of police. I believe in the creation of alternative strategies and alternative first responders. But I’m more focused on that than my hatred.

■ I caught a gun case because I was stolen from and I beat this guy up outside a club. But now when similar things happen, I have learned how to address them with faith and prayer and calm. All of that helps my creative process, because I don’t end up in these anxiety-ridden, nerve-racking, crash-out spirals where I’m carrying a pistol at all times ’cause I’m so paranoid that somebody who I hurt now wants to kill me. I can’t make music like that. I can’t create like that. It’s too fucking stressful.

■ The same things that drove me towards suicidal ideation at age 5 or suicide attempts at age 22 were finding ways to manifest themselves in my creative process. Even when people could say I was on top of the world — I got this Kanye thing going on, I got this Jay-Z thing going on — in my mind, I felt like I wasn’t enough. And so to try to feel like I was, I would try to amass as many women as possible. And in the pursuit of that, there would be a lot of drugs to quiet all the noise. The drugs would make me feel like I’m on top of the world, but then I would crash hard. And in the midst of that, I’m trying to dominate in any way possible — if it’s violently, if it’s in music, whatever. I would be in the studio literally just beating my head, ’cause making music is not necessarily easy for me. I’d be doing so many drugs to try to enter a flow state, and I would just wear myself thin and deplete all the serotonin in my brain. So then I’m just super depressed and suicidal, the drugs are not working, the music’s not getting made, and I’m like, OK, cool, I gotta drive this car off the bridge. And that’s a terrible, vicious cycle.

■ Being at this place where I am now, so deep in my meditation and sobriety, if I’m having trouble in the studio and it’s not coming to me, I’ve already made the decision I will not be doing any drugs, I’m not gonna be calling any girl off Instagram to try to lose myself in sex, and I’m gonna come back tomorrow and try again.

■ I’ve been in a 12-step program called Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous. It was basically full of people who had damaged their lives, some irreparably, through sex and relationships. I even went to a sex addicts meeting once or twice, and I’m telling you, there are guys on Skid Row right now who still can’t stop masturbating. It doesn’t matter who you are or where you are in life, addiction is addiction. We’re all human beings. We just want to feel validated. We don’t want to feel pain. And so we escape those feelings in a host of different ways. But I realized that if I stop trying to escape those things, then I grow stronger.

■ I spent a lot of money I didn’t need to — on jewelry, cars, cribs. I mean, I hemorrhaged money. I spent $10,000 a month on rent. Completely foolish spending that I didn’t really grasp. And the thing is, the music business is so fucked. You’ll be a young artist with all this money coming in and you got people you pay to manage the money and help you make good financial decisions, and then those people fuck you over. It’s crazy.

“The drugs are not working, the music’s not getting made, and I’m like, Ok, cool, I gotta drive this car off the bridge.”

■ I went to Ghana in January with the intent to get off antidepressants, among so many other things. I’ve been on 10 or 15 different medications since I was 15. Only once in that span did I really have a working medication. That’s a dismal efficacy rate. So I just decided I didn’t wanna be in that game anymore. I was like, While I’m in Ghana, I’m gonna microdose — like, actually take the intended nonpsychoactive dose three days on, two days off, or whatever it was. I think we know how that ended up. But even when I caught that case, I was in such a strong place mentally and emotionally that I was able to maintain my faith and my good spirit, even through being incarcerated.

■ When I got locked up in Virginia, I was so accustomed to meditating that I just instantly went into meditation mode and transported my mind and my spirit outside the jail. I was meditating for hours on end and literally manifesting the things that were gonna take care of the problem at hand. I was on the phone with my guy, and he was telling me that the lawyer was gonna cost $20,000. And instead of stressing about it, I just put a prayer up, like “I thank God that the money is gonna come to me in the perfect time and in the perfect way.” And I just believed it. I got out on a Tuesday, and on Wednesday a friend of mine had me come perform at a club and gave me $20,000 cash. I have come to realize that by living upright and practicing faith as an act of will, I don’t have to finesse and finagle my way through this shit. I can just gracefully skate through.

■ I’ve been studying Islam for a year, and in Islam they say that a good deed done in silence calms the anger of Allah. It’s almost like spiritual currency. When you make a lifestyle out of this shit, as I have, you want it to be seen so that the attention grows and the resources increase and you can have a larger impact. But you also can’t get caught up in this activist clout shit. There are people out here literally just jumping in front of a camera, handing a hamburger to a homeless person. I’ve come to understand that I am making deposits in the bank of the divine by helping somebody, whether or not the world sees what I’ve done.

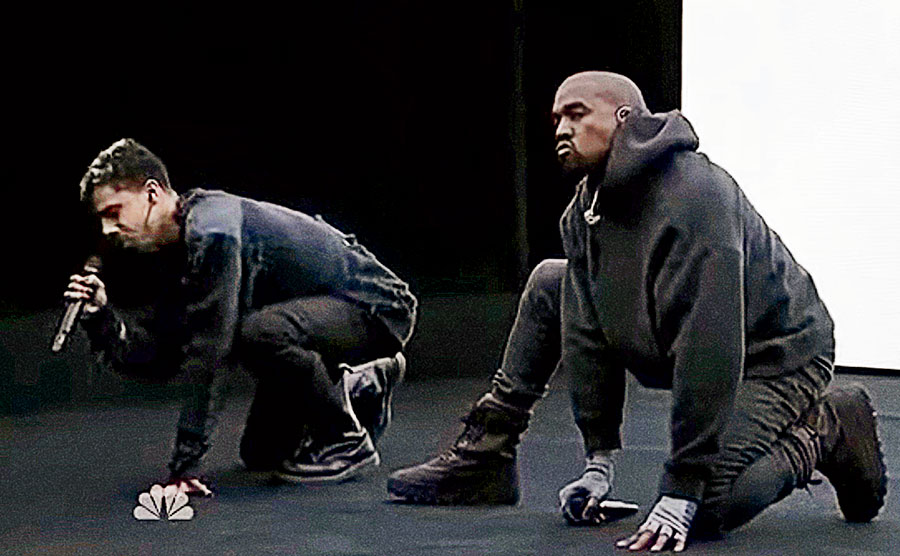

■ One of the things I learned from Kanye is the power of collaboration. I used to feel that I had to fully form every idea by myself. It wasn’t until seeing the way he would enlist the best people for every job and have them all approach a song from different directions that I really started letting people in on my creative process. The Saturday Night Live performance with him opened a lot of doors for me. I remember backstage, people like Bill Gates and Dave Chappelle coming to show me love. It was a major moment. And a very creative performance, too. That’s the thing about Ye: He’s a full-blown creative director at all times. That performance was a big turning point for me. Many people were seeing me or knowing about me for the first time. And there were definitely people hating, like, “Oh, that’s weird, you’re dressed up like a wolf and crawling.” Whatever could be said about it, it was super major.

■ Pharrell gave me one of the most powerful life lessons. First day in the studio, we made some great shit. Second day, on my way over there, I received a call from a person who was once a friend of mine. I was scheduled to do a music video with him. He was a producer. It was gonna cost too much to shoot it in Chicago, so we had to pivot it to L.A. But we had already made deposits to the tune of about $12,000, $15,000. Well, now he was saying the money was already spent. Then he accidentally sent a message to my phone that said, “If they call you, don’t tell them anything, play stupid.” I was so mad. I was on the phone with him, like, “I’m gonna kill you.” I had a plan. I was gonna stake out his place, and if I didn’t get my money, I was gonna destroy all his computers. When I got to the studio, I was visibly upset. Pharrell was like, “What’s going on?” I told him, and he was like, “Man, you are lucky for three reasons. First, this is not gonna tank you, it’s not gonna send your family into financial ruin. Second, you don’t have to be the person who looks at himself in the mirror and knows that he steals from those he calls a brother. And third, you have the ability to move on from this situation.” And that was so profound to me.

■ Omari Hardwick is narrating my new album. He’s best known for playing Ghost on Power, and he’s a good friend of mine. A year ago, when I had all those things going on in the streets and with violence, he told me a story about a rapper we all idolized who had been killed. “Protect your gift” is what he told me. And I realized that every time I brought myself down to the level of ransacking the studio of the producer who stole from me, or carrying a gun around with me, or flippantly putting mushrooms in my bag, I wasn’t protecting my gift. I never really thought about it that way before.

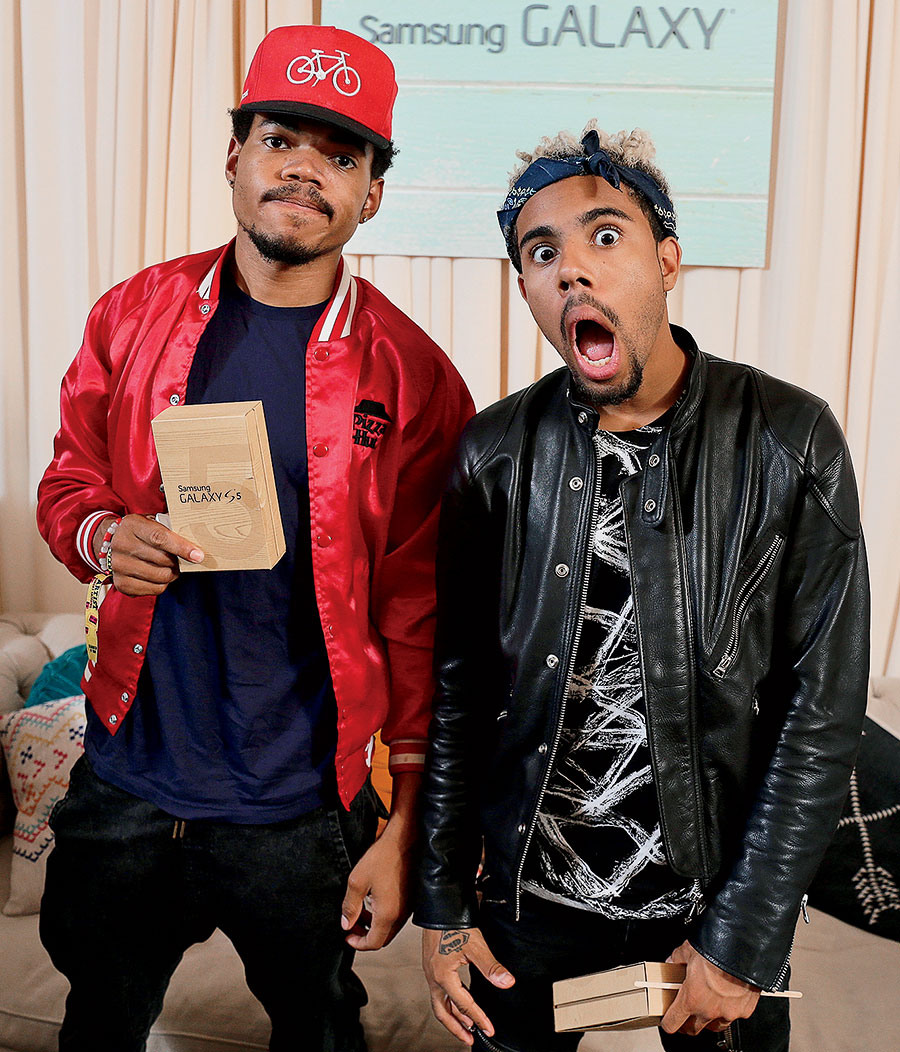

■ When Chance [the Rapper] really blew up, and then I blew up, there were some years when we were not close, when we were at odds. Our relationship was sour. I definitely had some jealousy. Brothers fight. Add in ego, money, and fame, and that’s a recipe for disaster. Time and growth have shaped us both to be much better than we were. And I’ve come to a place where I recognize that my path is my path. It’s not to be compared and contrasted with anybody else’s. Our relationship is probably better now than it’s ever been.

■ I consider myself somewhat of a comedian. I got standup jokes written and everything. I know I seem really serious because of the things I’m talking about, but anybody who knows me knows I joke too much. That’s something I’m working on now, because my whole life I’ve been the person who would be chasing the laugh to where I’ve said really ridiculous, disrespectful things and offended people badly. Sometimes I need to shut the fuck up.

■ Since childhood, my life was this cycle of constant depression and fear. I always felt at the mercy of those things, and I didn’t know if I could survive. I’ve had the opportunity to learn from my mistakes and not be swallowed by them.