The most famous movie theater in television history wasn’t a real place — but it was based on a real place. From 1925 to 2012, 445 Central Avenue in Highland Park was home to an unassuming two-story movie house. It opened as the Alcyon and in 1965 was renamed the Highland Park Theater. It also appeared in movies; in Tom Cruise’s breakthrough Risky Business, his character drives past the unmistakable Tudor Revival façade and color-blocked marquee.

In its final years, before it was abandoned, then demolished in 2018, the theater housed four screens. But in its glory years, before it was subdivided in an attempt to compete with larger suburban multiplexes, it held just one cavernous auditorium. It even had a balcony.

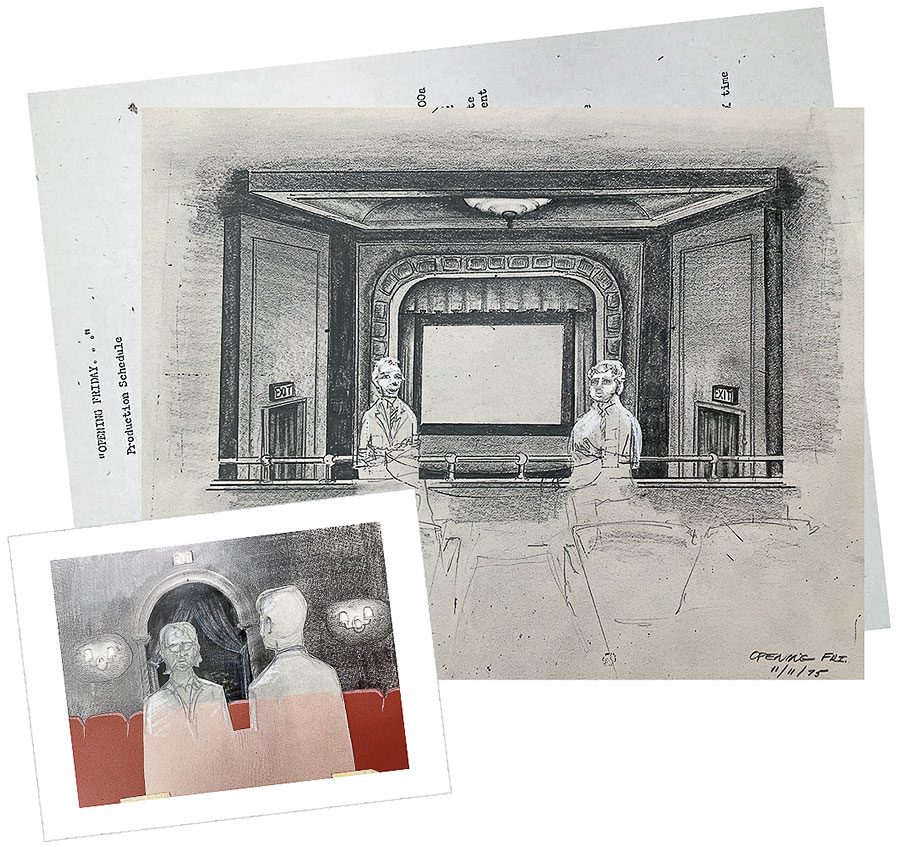

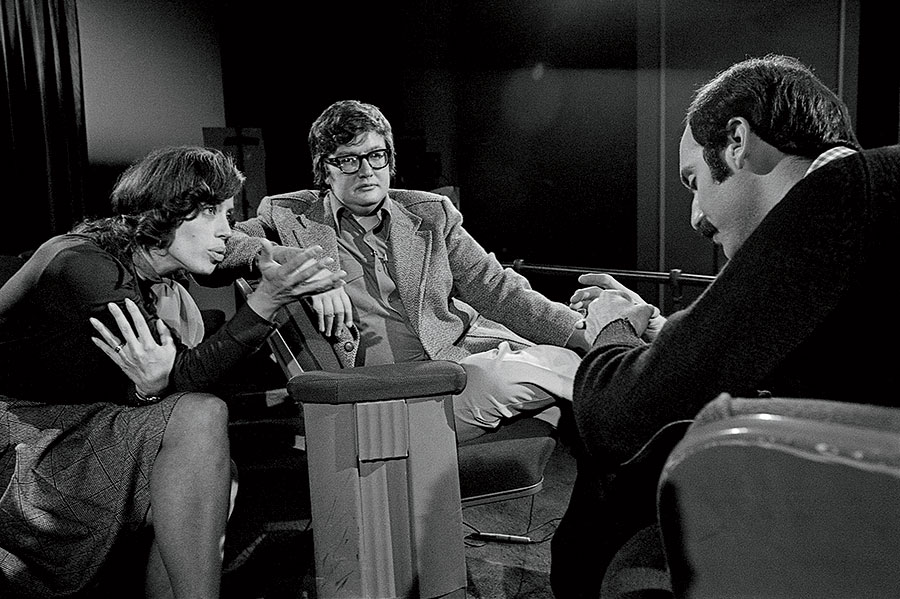

Having grown up in Highland Park, Michael Loewenstein knew that balcony well. He had been at WTTW as a scenic designer for 15 years when he was approached in 1975 to work on the set for Opening Soon … at a Theater Near You, the public station’s planned movie review show starring Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert and the Tribune’s Gene Siskel. Instructed to design a movie theater, he immediately thought of the old Alcyon.

“It had a Spanish look to it, with rough plaster walls,” Loewenstein says. “It was sort of a moderate version of some of the big movie palaces downtown. And that was good. From a television point of view, it had some detail to it, and also this certain look, this Spanish look.”

But copying the appearance of even a moderately sized movie theater was difficult in WTTW’s cramped studio space. Loewenstein initially wanted to put Siskel and Ebert into the theater’s orchestra section, but he quickly realized that in order to “get the feeling of the volume” of a big auditorium, he would have to cheat, using a technique called forced perspective, a trick of photography and architecture that fools the human eye into believing something is bigger than it actually is. “To make it real size would have made weekly setup impossible,” explains Loewenstein. “So I started thinking about using the balcony.”

That balcony — “the Balcony,” as it was affectionately known through the years — featured full-size seats acquired from old theaters and furniture companies. (Loewenstein’s files include an ad for Chicago Used Chair Mart on West Grand Avenue that boasts, “We can make them like new … cheaper than you think!”) Everything beyond the Balcony’s brass rail was a miniature, built about one-third of the size it would be in an actual theater. Loewenstein’s architectural drawings for the original Opening Soon set reveal just how meticulously the forced perspective had to be planned. The edges of the set’s side walls were different heights; closer to the camera they stood 15 feet high, but the one farthest from the camera measured just 13 feet, seven inches. Even the lighted “Exit” signs hanging over the theater’s doors had to be specially made at a slight slant away from the cameras.

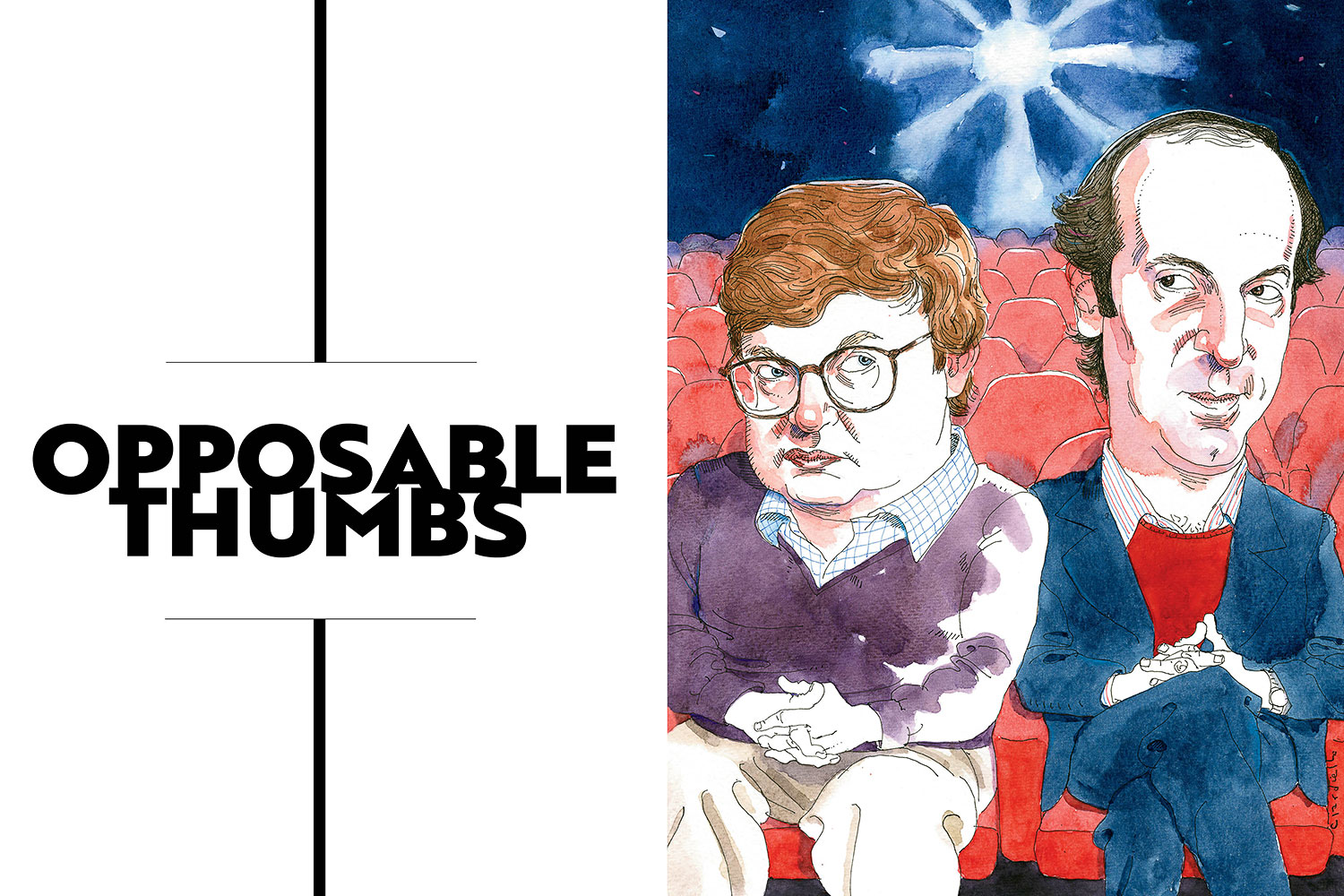

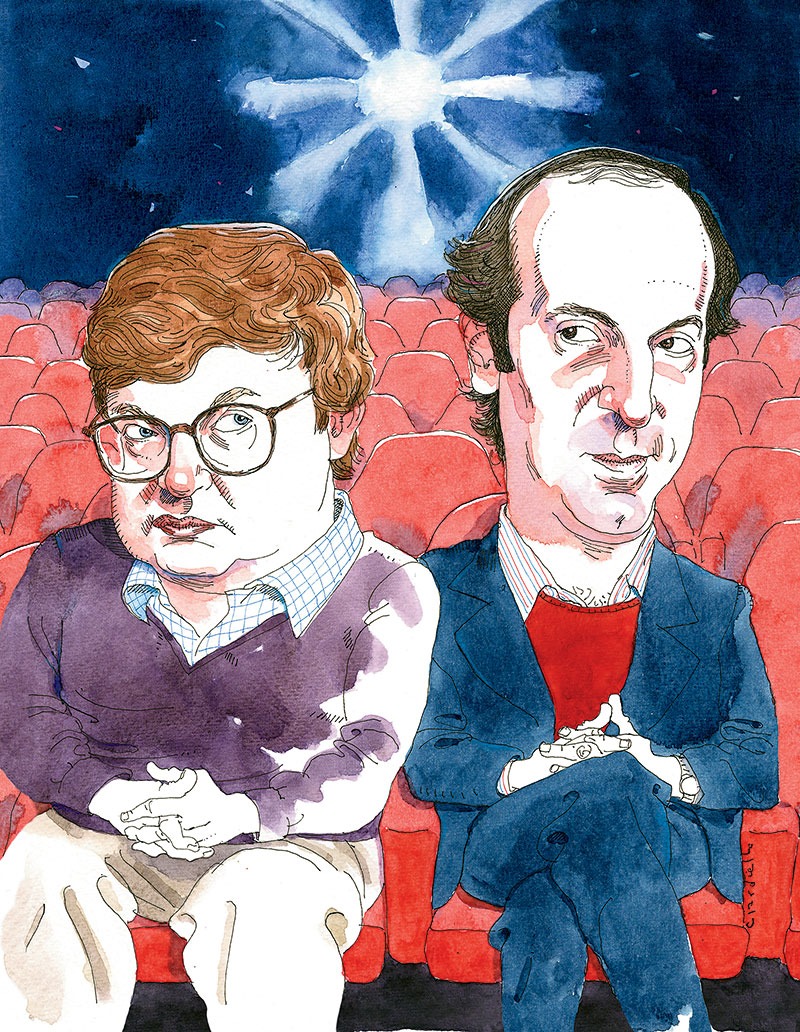

A technique called forced perspective fooled viewers into believing the Opening Soon set was bigger than it actually was. From exactly the right vantage point, it looked like a homey neighborhood movie house. The inspiration: the old Alcyon in Highland Park, where the scenic designer grew up.

From exactly the right vantage point, forced perspective made the Opening Soon set look like a homey neighborhood movie house à la the Alcyon. Later versions of the Balcony would enhance the simulation even further with tiny versions of orchestra seats. (Crew members nicknamed them “the tombstones.”) The set was so convincing that the show regularly received letters from fans who claimed to recognize the theater where they shot the show.

Loewenstein’s balcony had two rows of chairs, with four seats on either side of the center aisle. Siskel sat in the first chair on the stage-right side of the aisle; Ebert in the first on the left. For two decades, those seats were their TV home. But even that became a source of competition between the men, according to Mary Margaret Bartley, who worked with Loewenstein on designing later versions of the Balcony for what would become Siskel & Ebert.

The nature of TV production required the two critics to appear to be the same height, which they were not; Siskel was several inches taller than Ebert. “So Roger had a cushion to raise him up so that his head height would be similar to Gene’s,” recalls Bartley. This created a second problem: Now Roger had a cushion and Gene did not. “Well, then Gene had to have a cushion, too,” Bartley says with a laugh.

The solution the crew eventually reached: Siskel received a tiny cushion, while Ebert sat on a much larger one. Sitting on their respective cushions, they looked about the same height on camera. (When Siskel & Ebert traveled to Florida to record shows at the Disney–MGM Studios theme park, the two pillows had to be shipped to Orlando to ensure cushion parity continuity.)

Siskel and Ebert would spend a lot of time in Loewenstein’s Balcony over the next several decades, but never more so than in the show’s early years. When Thea Flaum took over the producing duties on Opening Soon … at a Theater Near You, she was responsible for one 28-minute episode a month — and generating that much content every four weeks proved to be a struggle. “It would take eight hours to get one show in the can, with breaks for lunch, dinner, and fights,” Ebert once said of the program’s early days.

The hosts’ issues as they tried to turn an unsuccessful pilot into a successful series were twofold: They didn’t know how to work on television, and they didn’t know how to work with each other. Often, one issue would exacerbate the other. From the pilot episode of Opening Soon … at a Theater Near You, the show opened with the hosts introducing each other rather than themselves.

“The name of the show is Opening Soon … at a Theater Near You, two critics talking about — and sometimes arguing about — the new movies in town. This is Roger Ebert, film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times,” Siskel would say.

“And across the aisle from me is Gene Siskel, film critic for the Chicago Tribune,” Ebert would respond.

But Ebert had won a Pulitzer Prize for film criticism shortly before Opening Soon began airing on PBS, and it was decided that detail would get included in his introduction. After all, few shows on television in 1976 could boast a Pulitzer Prize winner as cohost. Which meant that, episode after episode, Siskel had to not only introduce his rival but also remind the audience that his rival was a Pulitzer Prize winner. And he had to do it all with a cheerful smile on his face.

“I think Gene was insecure about his writing,” says assistant producer John Davies. “So whenever Gene would give me his copy to type up, he would never write ‘Pulitzer Prize–winning film critic.’ He would write things like ‘And to my right is Roger Ebert, film critic for the Las Vegas Shopper News.’ That’s what would go in the teleprompter. And of course Roger would see it, but he knew Gene was going to say it right. And Gene did — but during rehearsal he would say, ‘And to my right is Roger Ebert, film critic for the Las Vegas Shopper News.’ He just had a hard time saying it right. It was a joke, and yet it wasn’t a joke.”

Ironically, given Siskel’s insecurities, Ebert had just as much trouble, maybe more, learning to write film criticism for television. By all accounts, Ebert was the more naturally gifted writer of the two — in print.

“When he typed a review on an old typewriter,” says staffer Ray Solley, “he typed faster than you could possibly imagine. And he would never make mistakes. He could knock out a several-hundred-word review in a matter of minutes and zip it out of the typewriter and hand it to the editor.”

But that was not the same as writing for television. On Sunday mornings, Siskel and Ebert would schlep over to Flaum’s house, where they would all sit around her dining room table, going over their typewritten scripts — line by line, and in some cases word by word — to make them work for a TV audience.

“Roger, you’re such a wonderful writer, but you know the show is only half an hour long. That review won’t fit. And Gene has to do something, too,” she once advised during one of these intense training sessions.

“But I worked on all of this! It’s all great,” he said in frustration.

“That,” she replied, “is what the newspaper is for.”

On one episode, Davies was typing up Ebert’s script and happened to see Ebert’s review for the same movie that was going to run in the Sun-Times. “I thought the review for the paper was better than the one for the TV show,” Davies remembers. So he decided to change the script and add back some of the material from Ebert’s print review. “I had not yet understood,” Davies admits, “that the TV script needed to be more conversational.” Big mistake.

When the revised script appeared in the teleprompter, Ebert recognized it immediately — and was not happy.

“Who did this? Who changed this?” Ebert yelled.

The rest of the staff slowly backed away from Davies. At least that’s how he remembers it.

Eventually, he admitted it was him.

“Don’t ever do that. Don’t ever change something I give you to type up. You type it up the way I gave it to you. Going forward, my new name for you is going to be ‘the Functional Illiterate.’ ” Davies says Ebert did call him the Functional Illiterate for “a while,” until Siskel finally told him he needed to stop.

“They were never going to be malleable by TV standards,” adds Solley, who describes Siskel and Ebert as two artists who were difficult, iconoclastic, and perhaps even dysfunctional. “They would be willing to change their outfits, or Roger’s glasses — what the best size would be, making them nonreflective. That was not an issue. But if you took a look at their copy and said, ‘What you wrote about that movie doesn’t make sense. I’ve not seen the movie nor read the book the movie was based on, so therefore I have no idea what you’re saying,’ then there would be huge arguments. Things like ‘How dare you edit my copy!’ and ‘I won a Pulitzer Prize, what have you won lately?’ So there was a great deal of learning on our part of how do you deal with people that know what they’re doing and have a process and a system, and how do you take your process and your knowledge and meld that?”

Siskel and Ebert even addressed onscreen the tension between them, in a 1979 episode, during a segment where they answered viewers’ questions. “Why don’t you guys have a few drinks together?” one said. “You don’t seem like you like each other very much.”

Ebert replied, “We have been competitors for 10 years. You work for the Tribune, I work for the Sun-Times in Chicago, the two morning newspapers. So professionally we are competitors.”

Siskel replied, “Yes, I like to beat your brains out in print anytime I can.”

“OK, well, I always enjoy doing that, too. But I suppose I have a grudging respect for you as a film critic,” Ebert said.

“I suppose I do, too,” said Siskel.

“Right. And when we leave the studio, we drive in separate directions in separate cars,” Ebert quipped.

To try to get everyone on the same page — and to bring a little more cohesion between the two stars — Thea Flaum instituted a policy: As production began on a new episode, the cast and crew would assemble in Conference Room A at WTTW and look at the previous show.

“She would have a watch-and-comment-and-learn session with the two of them,” Solley explains. “They learned from watching and from being tutored by her before they went into the studio for the next show. So anything that had slipped backwards from the past couple of tapings would be addressed quickly before you went into the next tape. She was responsible for keeping a pretty tight rein on the process, and on them. And they ended up loving that about her.”

“It would be the director, the producers, me, and Gene and Roger. That’s a very good way to get better,” Flaum adds. “Because you’ve seen it, and then you go down and you do it again, and you do it better; you don’t make the same mistakes. We did that for years.”

The hosts’ issues as they tried to turn an unsuccessful pilot into a successful series were twofold: They didn’t know how to work on television, and they didn’t know how to work with each other.

Among the mistakes that were observed and corrected in those early review sessions, one of the biggest was simply the way both men carried themselves on camera. For all of the tension between the hosts and the crew in the first months, none of it translated to the screen. On camera, Siskel and Ebert continued to appear lethargic, uncomfortable, and sometimes downright bored. Ebert would lean back with his right arm draped across the back of his chair. Siskel crossed his legs and slouched. They looked like they were recording the show after sitting through an all-night movie marathon.

With Flaum’s help, they started improving their energy level and posture. She also worked with them to lay out ground rules for the show in order to make it as useful and interesting to viewers as possible.

The first rule, Flaum says, was ensuring that they were only going to “talk about the things that people could see.” She explains: “People watching television aren’t stupid. So you can talk about anything, but if you’re going to talk about lighting, point out what there is in the clip.”

Another rule: sharper onscreen outfits. Siskel and Ebert would never be mistaken for movie stars, but in early episodes their clothes were downright ugly: loud patterns, cream turtlenecks, and massive lapels. Flaum instructed them to purchase new wardrobes. Siskel would later describe the look they settled into as “blazers and sweaters, the same kind of clothes people really wear to go to the movies on a Saturday night. We’ve always wanted viewers to feel as if they were just eavesdropping on a couple of guys who loved movies and were having a spontaneous discussion.”

The show emphasized that idea by having Siskel and Ebert continue to talk even as the lights dimmed in the Balcony and the closing credits began to roll. It suggested these guys would be chatting whether there were cameras present or not, and it offered a subconscious invitation to the viewer: Come back next week, and you’ll see them in the same seats, having the same great conversation. (During one talk show appearance, Siskel confessed that when they couldn’t think of anything to say during the final fade-out, he and Ebert would just say “Blah and blah and blah” over and over until the director called cut.)

Little by little, the two got more comfortable with each other and with the cameras. Their onscreen demeanor improved, and so did their ratings. By the second episode, the Central Educational Network, a subdivision of PBS, wanted to air Opening Soon beyond Chicago. By the third, they were on 80 public TV stations around the country.

As the show got bigger, its title became a problem. Opening Soon … at a Theater Near You was a mouthful. It was also so long it couldn’t fit into the most essential promotional tool any television show in the mid-1970s had: the listings in TV Guide. Most newspaper listings condensed it, typically to just Opening Soon — which wasn’t very descriptive.

“The internal joke,” says Ray Solley, “was that ‘Opening Soon’ could be a mall. It could be a shoe store. So that didn’t help us. We needed a movie-related title. Thea’s husband at the time came up with one. He said, ‘Let’s call it Sneak Preview,’ to which Thea said, ‘Well, but it’s more than one movie in a show.’ Then he said, ‘Sneak Previews!’ ” (“Actually, about half a dozen people suggested the name Sneak Previews,” Flaum said in a 2011 interview.)

Thanks to its increasing popularity on PBS stations around the Midwest, Sneak Previews expanded to a weekly show in the fall of 1978. When it did, it also got a new opening credits sequence, scored to a song called “Summer Vacation,” which was originally written for an episode of the 1950s sitcom The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Set in a bustling movie theater, the Sneak Previews credits opened with the title on a glittering theater marquee. An unseen patron buys two tickets — which also have the Sneak Previews title on them. The hosts’ names appear on a popcorn bucket and a box of candy. (Unlike in later iterations of the series, Ebert was credited first, followed by Siskel.) Then the soda machine malfunctions, leading to a series of shots — designed by the show’s first director, Patterson Denny — where hands frantically pound on the various soda buttons and the coin return lever before a Sneak Previews–branded fountain cup drops into a dispenser upside down, sending soda flying everywhere.

Intentionally or not, the credits captured the mood of the occasionally volatile Sneak Previews set, where things could descend into chaos at a moment’s notice. “There were a lot of arguments about scripting and movie choices,” says assistant director Laura C. Hernandez. “It just seemed like the discussions were big and tense about a lot of those things. Movie clip choices — that was always a bone of contention.”

Clips became one of Sneak Previews’ secret weapons. This was the late 1970s, a time when broad use of the internet — much less the Internet Movie Database — was still almost 20 years away. There was no YouTube filled with movie trailers and film clips. Honest, unbiased information about movies — especially the latest ones opening in theaters — was rare and difficult to come by.

In most cases the studios themselves did not make clips available even for journalists — and when they did, they weren’t always relevant to the topics Siskel and Ebert wanted to discuss — so Sneak Previews made its own. “Someone from the staff always went to the screenings with Gene and Roger,” explains Flaum. “Gene and Roger would call out particular scenes where maybe there was a point they wanted to make, that we would use.”

But it wasn’t as simple as running a stopwatch and jotting down the exact time when that particular scene appeared — because this was the late ’70s, when movies were projected on enormous reels of 35 mm film. Each reel contained about 20 minutes of the movie, and the changeovers between reels were indicated by cue marks — little white circles in the upper right-hand corner of the frame. So it was up to the staff member to keep constant watch on those reel changes, because when the screening was over, they would take those specific reels (and only those reels; they weren’t allowed to take the entire movie) and haul them in enormous 20-pound cans to a local film transfer facility, where they would copy the specific scenes to videotape.

It’s hard to believe that Hollywood studios gave a television show they had no oversight over the authority to freely use clips of movies, but that’s how things were done for years and years. (“I can’t imagine the legalities of that, but we got permission. We never had it in writing,” Ray Solley marvels.)

The only director in those days who pushed back against the practice was Woody Allen, then at the zenith of his power. When Allen released Manhattan in 1979, he provided just one clip for any and all coverage, and, of course, it wasn’t one of the scenes Siskel and Ebert wanted to talk about. “Thea Flaum’s mantra was ‘Somewhere, someplace, there’s a person sitting at a desk that can say yes,’ ” says Solley. It was his job to find that person.

Solley called the film’s Chicago publicist and got nowhere. Then he talked to the publicist’s boss; no luck there, either. Then he called Allen’s powerful agents and producers, Jack Rollins and Charles Joffe, and left a message explaining the situation.

Two days later, Woody Allen called the Sneak Previews office at WTTW. “I know Roger, I know Gene, I love them both,” Allen said, according to Solley. “I don’t have much time to talk, but I am happy to help you get a clip. What is it that they want and why?” Allen wasn’t just helping out of the goodness of his heart; he was subtly trying to pry loose some information about what the critics were planning to say about his movie.

Though selecting, lugging, transferring, and then returning the heavy canisters of films was, in one producer’s words, “a huge process,” it was also one that made Sneak Previews unique in its heyday. Nobody else on television had the clips it had, giving movie lovers extra incentive to tune in. “It just seemed to me that we needed to do things that would distinguish us from the stuff that they would now be seeing every day on the Today show,” explains Flaum.

Although Siskel & Ebert became synonymous with its thumbs-up or thumbs-down ratings system, that came later. In the days of Sneak Previews, the show concluded with a roundup of the episode’s reviews and a “yes” or “no” vote for each film, a choice that was only settled on after what Flaum calls a series of “long arguments” about the best way to rate movies on the show.

Initially, both Siskel and Ebert insisted that Sneak Previews should use the star ratings they assigned to movies they reviewed in the newspapers. Flaum and the rest of the staff were equally adamant it was a bad idea, mostly because it was confusing. Some film critics used a scale from zero to four stars; others used zero to five. Some only used whole stars, while others also gave half stars.

With the stars vetoed, the discussion then turned to the possibility of assigning letter grades like in school: A’s, B’s, and so on, down to F’s for the real stinkers. But that presented similar issues, in that some grades would leave the critics’ final judgments somewhat ambiguous. (Was a B− a recommendation? Was a C+ a warning to stay away?) Plus, Solley claims, there was some concern that public television assigning grades to movies would play into the stereotype that PBS shows were “educational TV.” That evolved into the simpler suggestion of “pass” or “fail,” but calling every movie Siskel and Ebert didn’t like a “failure” felt too extreme.

They would deliberately avoid hearing each other’s opinions until they showed up for a taping. “The spontaneity offered in that crosstalk was very valuable and very real to the success of who they became,” says an assistant director.

“So then it went to ‘OK, what else can we do that’s clean and clear and is very binary?’ ” recalls Ray Solley. The Sneak Previews team realized that “yes” and “no” answered one of the questions at the root of every movie review: Should I spend my time and money and go see it?

Despite Sneak Previews’ expansion into the rest of the country, Siskel and Ebert were still not happy with the show, and especially with its prolonged production schedule. Due to their struggles with teleprompters, endless rehearsals, and each other, half-hour episodes still took all day to record. Shooting would begin around 11 o’clock in the morning, then break for lunch, then record more, then break again, then finally finish up by 7 or 8 o’clock at night. It was an arduous process, with Siskel and Ebert at each other’s throats — and sometimes at the crew’s throats. Something had to give.

Like everything else with Siskel and Ebert, the big breakthrough came because of a fight. In a 2005 interview, Ebert detailed what happened at one recording session in 1981. It was a Thursday, the day episodes were taped. And this one was going really slowly. Siskel and Ebert did take after take, broiling under the hot studio lights.

At last, they nailed a review they were both satisfied with. But Ray Solley, who by then had replaced Thea Flaum as the show’s producer after she was promoted to executive producer, was not. Those hot studio lights had caught a reflection of Siskel’s wristwatch, producing a distracting flash in the camera. They would have to try the review again.

“I just want to tell you,” Siskel said to Solley, “that if we have to do this again, I’m going to get up out of this chair, and I’m going to walk out of the studio and out of the station and never come back.”

With that, Solley had had enough. He threw his clipboard down and marched out of the studio. “The next week,” Ebert recalled, “our intern produced the show. Her name was Nancy De Los Santos. And she said, ‘I’m gonna just let you guys talk. Because you can’t really remember all of your three-by-five cards anyway. But you’re better at just talking to each other.’ And we did a show and said, ‘This is the way it’s supposed to be.’ And so we went into Thea and said, ‘Thea, we want Nancy to produce the show,’ and that was fine with Thea. So Nancy became our producer. And that was the beginning of things getting easier.”

At least that was how Ebert told the story. Nancy De Los Santos tells it a little differently. For one thing, she wasn’t an intern on Sneak Previews one day and a producer the next. Though De Los Santos started at WTTW as an intern, by 1981 she had worked her way up to the position of assistant producer. There were no three-by-five cards involved with the show by that time, either — index cards and on-set notes hadn’t been used since the earliest days of Opening Soon … at a Theater Near You. But she does remember there was a fight over a take that got marred by a flash of light off Siskel’s watch, and in her telling, she picked up the reins (and the literal clipboard) after Solley left the set.

Solley doesn’t remember the incident — though he says if De Los Santos says it happened, then he believes her. “But,” he adds, “there was never a moment of I walk off the set on the Wednesday or the Thursday and she takes over the next Wednesday or Thursday. It was much more evolutionary than a story of a weird problem and a blowup and a change of leadership in the space of an hour.”

Solley actually returned to finish the remainder of the season, although De Los Santos was eventually promoted to the role of producer. And whether it was the matter of one big fight, or a slow accumulation, the Sneak Previews formula did change. “Instead of doing it over and over again to get it right, we would allow it to be a little sloppy,” Ebert said in that 2005 interview. “Gene and I agreed: It’s better for the people at home to feel that we are having the conversation for the first time. And that led within a very short time to the concept of ‘the First Take Show,’ where basically the show is done in real time.”

“That’s one of the things Ray Solley did too much of — he overrehearsed them,” echoes assistant producer John Davies. “And they really did not like that. I’m not saying Ray was a bad producer, but he was a bad producer for them. They wanted that crosstalk where they took each other on and argued. They wanted that to be natural. And Ray would break it all the time. ‘No, guys, you didn’t make your points cogently enough. It wasn’t smart enough. I don’t get why you disliked the movie. I don’t understand.’ And it would really piss them off.”

From that point forward, Sneak Previews and its subsequent iterations prioritized authenticity of interactions over technical perfection. If there was a minor flub or a slightly awkward shot, but the debate between the two hosts was particularly heated, it stayed in the show. Gone were the hours of rehearsal and the countless retakes. Rather than trying to perform the roles of the smartest and cleverest pundits, Siskel and Ebert would simply be themselves and react to each other accordingly — which, because they still regarded each other suspiciously and often disagreed violently with each other’s opinions, resulted in some thought-provoking and surprisingly dramatic television.

These lively, unrehearsed “crosstalks” became the key to the show’s popularity. Siskel and Ebert would deliberately avoid hearing each other’s opinions until they showed up at WTTW for a taping. What you saw onscreen were their genuine reactions to each other. “The spontaneity offered in that crosstalk was very valuable and very real to the success of who they became,” says Hernandez, the assistant director. “And they were smart enough, and the people around them were smart enough, to know what that magic was.”

The more honest and raw Siskel and Ebert got, the better the show got, and the better the show did. By the early 1980s, Sneak Previews aired on hundreds of PBS stations around the country, including in New York and Los Angeles — markets that initially refused to carry the show because they believed two critics from Chicago had nothing to offer their high-brow audiences. Eventually, though, the pair’s gift for natural conversation and debate — and Sneak Previews’ ratings — became undeniable.