Disembark in 1907 New York, trek a few blocks into the city, and what do you see? The glittering Great White Way of Broadway, where even the most dazzling vaudeville >>>>

|

|

star can’t hold a candle to the brilliance of a billion light bulbs. For one awestruck 13-year-old immigrant, newly arrived from Ireland with nothing but $10 in his pocket (“Literally,” his great-grandson says; “I have the charter”), the view was enough to inspire a dream that would fuel four generations, to date, of filial pride.

Fast-forward to 1923, and Thomas F. Flannery Sr. has settled in Chicago with the basics of electrical engineering under his belt. With the memory of Broadway’s bright lights burning in his brain, Thomas launches a sign maintenance company. He calls it White Way. “Back in those days, the only thing that was really lit up, whether it was New York or Chicago, was these theatres,” says the great-grandson, Robert “Bob” Flannery III. And the signs? “That was their calling card.”

|

By 1940 White Way Sign and Maintenance Company had branched into the business of manufacturing marquees. From Beverly to the Far North Side, Chicago’s theatres bore the White Way stamp, albeit in much smaller type than the names of the stars promoted above.

Today, in the post-post-golden era of the silver screen, the 150-employee company, headquartered at 1317 North Clybourn Avenue, traffics more in scoreboards than in movie marquees. But for the Chicago and other legendary theatres that still employ its service, White Way continues to clean and repaint and renovate signs. “That’s our bread and butter,” Bob says. “That’s how we started.”

Here’s a look back at a shining past:

HOW MANY EMPLOYEES DOES IT TAKE TO SCREW IN A LIGHT BULB? Theatre managers knew it was 9 p.m. Thursday when the weekly caravan of 20 White Way trucks (at right) descended on the Loop to reconfigure signs for Friday releases. Once the Loop was finished, workers would fan out, often updating neighborhood marquees until 2 or 3 a.m. “The main thing was to double-check afterwards that everything was spelled right,” says neon shop foreman Bill Ganley, a 40-year White Way veteran. Here, the Adler and Sullivan–designed Garrick at 64 West Randolph Street in 1958, demolished amid protests in 1961. |

|

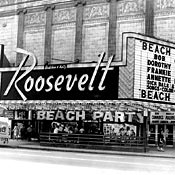

BRIGHT LIGHTS, BIG CITY In the 1930s and 1940s, when one square block in the Loop could boast as many as five movie houses, signs were integral to attracting audiences. “Each theatre . . . tried to one-up each other,” White Way executive Bob Flannery says. When theatres like the now demolished Woods, at right, in 1959 at 54 West Randolph Street, and the Roosevelt, above, in 1963 at 110 North State Street, began to close, many signs were lost. But some survive in the permanent collections of institutions such as the American Sign Museum in Cincinnati, Ohio, and the Chicago History Museum, which houses the original Biograph sign. |

|

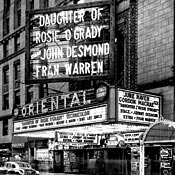

LIGHT FANTASTIC At left, the Oriental-now the Ford Center for the Performing Arts, Oriental Theatre-in 1950 at 24 West Randolph Street. This sign comprised about 4,000 bulbs; letters in the illuminated names on top each contained 10 to 20 frosted yellow 25-watt bulbs. “Frosted bulbs were used to create the proper light-the proper illusion, shall we say-as opposed to a clear lamp that would be too harsh,” foreman Bill Ganley says. The marquee was bordered by 11-watt bulbs; the canopy’s underside was illuminated by 25-watt bulbs; and the ad panels, here advertising singer Johnny Desmond’s live stage show, were lit by 150-watt floodlights. White Way’s bulb of choice? General Electric. |

|

TEAM PLAYER To this day, White Way houses both a full-time art department that creates logos, from fonts to flourishes, and a full-service construction shop. A stroll through the neon workroom reveals a display of phosphorescent bulbs in colors such as Amber Gold, Aqua Marine, and Neo Ruby. “The sign is the first visible thing a person sees about a business,” Bob Flannery says. “We get that.” Below, the now-defunct Varsity (1710 Sherman Avenue) in Evanston, 1953. At right, the former Harris in 1948, then part of a two-theatre compound with its sibling the Selwyn at 170-186 North Dearborn Street. |

photography courtesy of White Way Sign and Maintenance Company