Cincinnati, circa 1988, outside the Hilton hotel: The Cubs’ team bus idles, waiting to shuttle players, coaches, and broadcasters four blocks to the ballpark for that day’s game against the hometown Reds. While boarding, Steve Stone, the team’s television color analyst, passes a woman holding her daughter, a toddler, not much older than 2.

After Stone disappears, the child becomes upset. Boldly, the woman, daughter in hand, boards the bus and approaches Stone. "My daughter doesn’t understand why you didn’t recognize her," she explains. "She sees you every day."

This is his footprint. For 20 summers (from 1983 to 2000 and again from 2003 to 2004), he appeared before Cubs fans almost daily on WGN or the team’s assorted cable outlets—often for a full afternoon or evening. And because he was there every day and because so much of what he said made such good sense (a mix of candor, sardonicism, and clairvoyance), he became a piece of the Chicago summer, as constant as June, July, and August, and a source of rare comfort to Cubs fans. "People often ask me about the uniqueness, the mystique, the phenomenon of the Cubs," says John McDonough, the team’s president. "It’s the continuity: We’ve had the same logo for 85 years; we’ve been on the same radio station for 75 years; and we’ve been on the same television station for 60 years. Our fans become accustomed to things. Once they accept and embrace you, which they did Steve, they don’t want change."

Then, in late October 2004, Stone resigned, following a disappointing season and a lingering conflict with certain Cubs players and officials. But Stoney (his nom de hardball) left the Cubs; he did not leave Chicago. Each season since, he has returned from his home in Arizona, taking a one-bedroom apartment in River North and dispensing baseball wisdom three times a week on The Score (WSCR 670 AM), the local sports talk station. "Chicago is the place that means just about everything to me," he says. "Because I’ve been intricately involved with the baseball teams on both sides of town, they are so much a part of my baseball life that it wouldn’t seem the same being out of this place."

This year, the Cubs are managing to cling to contention even under the knowledge that the team is likely to be sold after the season by its parent, Tribune Company (also the owner of this magazine). Would Stone, now 60, like to be part of a new management group? "If somebody said to me, ‘You’ll be granted one wish, and it involves your employment next season, what would that wish be?’" he says. "It would be helping direct the Chicago Cubs in a front-office capacity."

* * *

Twice a week or thereabouts, Steve Stone walks the two blocks from his apartment to lunch at Harry Caray’s Italian Steakhouse on West Kinzie Street—the namesake restaurant of his late broadcast partner. Sometimes Stone eats alone, but usually he meets David Kaplan, a good friend and host of WGN 720 AM’s Sports Central. Although Stone drinks only water, he sits in the back third of the bar at a table against the wall, amid a constellation of the restaurant’s ubiquitous Harry silhouettes and caricatures. The bar offers him a vital accommodation—baseball. Twelve television sets surround his seat, the smallest ones featuring games of tangential importance, the larger screens reserved for the Cubs. He watches them all, but (unable to help it) he syncs himself to the Cubs broadcast.

"Better not pitch him low," Stone warns when Corey Hart (leadoff hitter, Milwaukee Brewers, the Cubs’ opponent on this day) takes to the batter’s box against Rich Hill (starting pitcher, Cubs). "He hits the snot out of the ball."

"A quick oh-two start," says Kaplan (de facto play-by-play guy), after Hill throws Hart a second consecutive strike to start the game.

"I wouldn’t even set him up," Stone counsels. "I’d throw a curve ball on the outside corner and strike him out."

After Hart has fouled off a few pitches: "He better throw a curve ball here, because [Hart has] been on the last two fastballs. Just keep it away, throw the curve ball, make sure it’s a strike, and he either gets a ground ball to the left side or strikes him out." One pitch later, Hart swings and misses—a curve ball.

That voice! The necks of those at nearby tables crane. In this case, their eyes are unimportant. It’s the cadence they recognize. The news moves around the bar quickly: "Stoney is here!" Many of them approach, more sentimental than awestruck. Once, the questions concerned only Harry. "It was never ‘Hi, Steve, how are you?’ or ‘How are the Cubs going to finish this year?’ or ‘Are you ever going to get married again?’ Nope. ‘Where’s Harry?’" Stone wrote in his 1999 memoir of Caray, naturally titled Where’s Harry? But now, even in the place where Harry once drank Budweiser after Budweiser, they want nothing more than to talk baseball with Steve Stone. He happily obliges, often absorbing them into his commentary, an at-home audience now a barstool away.

When watching the game, he shows few signs of partisanship. He views the sport more clinically. Individual plays matter little to him; it’s why they happen and how they fit into the tapestry of that particular game and season that seem to interest him. ("The guy has a Pentium chip," says his Score afternoon drive cohost, Dan Bernstein.) When someone talking about the Cubs makes a "we" or "us" reference, Stone often asks, "Is there a mouse in your pocket?" And yet, from time to time, he catches himself: "We acquired—well, ‘we,’ I use the ‘we’ still."

"I think he bleeds Cubs blue," Kaplan says. "I think it kills him that he’s not a part of this team."

* * *

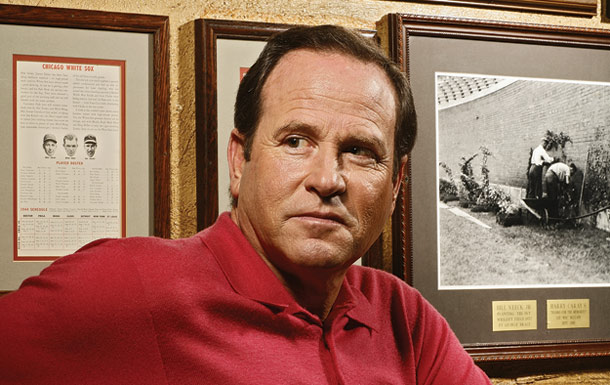

Photograph: Anna Knott

A few things about Steve Stone: He obsesses over properly barbecued ribs and chili, but most meals are an excuse to eat sorbet. He almost relocated to the Deep South only because of the apple caramel sorbet at The Ritz-Carlton in Atlanta. He watches Entourage, mourns the cancellation of Deadwood, and was appalled by the Sopranos’ finale. He has golfed with Alice Cooper. A Cleveland native, he earned a teaching degree from nearby Kent State University in 1970, the year Ohio National Guardsmen fired on campus war protesters. His baseball card says he stands five feet ten inches tall—a three-quarter-inch exaggeration in his favor. He fancies cowboy boots and Armani sunglasses. In conversation, he tends toward filibuster. Most baseball questions he poses are rhetorical. (He already knows the answers.) He listens to Rush Limbaugh, but has dined with the former Democratic vice presidential candidate Senator Joe Lieberman. Jerry Reinsdorf and George Will promptly return his phone calls. He played for the Cubs and White Sox (twice) in the 1970s but won the American League Cy Young Award with the Baltimore Orioles in 1980. He wears a ring on his pitching hand signifying this accomplishment. Of the Jewish pitchers in major league history (a small but distinguished group), he has won the third most games—behind Sandy Koufax and Ken Holtzman. He pitched the way he broadcasts—thoughtfully. As a broadcaster, he is uncomfortable only when the booth gets too hot.

"He’s brilliant, but at the same time I think he’s very sensitive," says McDonough. "He’s got a healthy ego, but he’s somewhat vulnerable. One of the things that I’ve said about being a very good friend of Steve’s for nearly 25 years is that my listening skills have improved dramatically. We’ve had conversations about that, and I think he’s become a very good listener."

"Steve is very opinionated, and I don’t mean that in a bad way," adds Chip Caray, who replaced his grandfather in the Cubs broadcast booth when Harry died in 1998. "He definitely has his ideas of the way things should be or the way things could go. I’ve told him, ‘Your biggest weapon is also your biggest obstacle, and that’s that you’re smart. You’ve got to tell everybody how smart you are. You say stuff in a way that pisses people off because they think you’re condescending.’" But what is interpreted as condescension, says Caray, is really conviction—strident and steadfast. "If he doesn’t believe it, he’s not going to say it."

Stone’s physical home is in Scottsdale, Arizona. (The two-year blip in his epic Cubs service was caused in part by health problems, including an Arizona lung disease called valley fever.) He shares the house with his wife of three years, Lisa—a family law attorney—and his two dogs, Tex, a greyhound, and Larry, a Rhodesian ridgeback. Friends say it’s a happy existence. He attends games in the Arizona Fall League, a developmental league for professional baseball prospects, and frequents his favorite restaurants with Lisa. "My wife is much smarter than I am," he says. "When she puts on her legal hat and distances herself from the emotional aspect of me being her husband, she’s very bright."

But in mid-January, his subconscious places him back on the mound and he begins to dream baseball again, which signals the nearness of spring training, which equals a new Cubs and White Sox season, which means his return to Chicago is imminent. So, at the end of March, he packs clothes and golf clubs into his black Mercedes CL55 (a vehicular embodiment of his dual localities, with its Illinois license plates and clock radio set to Mountain Time) and drives (sans Lisa, Tex, and Larry) the 1,825 miles northeast to Chicago. "This city has treated him so well," says Caray. "I think he’s found a home. As a baseball broadcaster, you’re a vagabond, living out of a suitcase for half of the year. To be able to put down roots and call a place home is a wonderfully rewarding and comforting feeling."

Stone’s River North apartment sits almost equidistant between Wrigley Field (4.74 miles) and U.S. Cellular Field (5.04 miles). Since it comes furnished, he adds only a stack of 2007 major league baseball team media guides, which line the bottom shelf of the side table nearest the phone, and a mishmash of his daily reading (the sports pages of USA Today and both Chicago dailies). A small den contains a computer that he claims he can barely use. Nonetheless, he is now interactive, complete with a blog, "Steve’s Pitch," the sum of his single-spaced, handwritten musings as dictated to his agent’s assistant and then unleashed upon cyberspace at stevestone.com.

The kitchen remains unsullied, as he eats his meals out (some combination of breakfast and dinner or lunch and dinner, never all three). Restaurants are of great interest to him, and he’s staked ownership in many of them over the years. An early investor in Lettuce Entertain You, he still holds a piece of Joe’s Stone Crab and Shaw’s Crab House, among others, and counts Rich Melman as a confidant.

Of dining, as with all else, his preferences are rooted and exact: "I don’t drink, so when I go into a restaurant, I don’t want to wait; I want to eat. As soon as I get done with the appetizer, I would like the salad. When I get done with that, I would love the entrée. Then I would love to get home and watch whatever baseball is on television. I try to get in before dark."

* * *

As for that nadir, 2004: The battle began in late July, when Cubs left fielder Moises Alou told the Chicago Sun-Times that Stone and Caray didn’t praise the team’s hitters enough. It intensified that August when relief pitcher Kent Mercker angrily confronted Stone on the team plane two days after Mercker had called the press box midgame accusing Stone and Caray of complimenting the opposition. (The offending observation: Despite giving up six runs, the Houston Astros’ starting pitcher, Roy Oswalt, had pitched well considering the late August heat.) The discord culminated in the final week of the season when Stone upset manager Dusty Baker and general manager Jim Hendry with pointed comments about the team on Kaplan’s radio show. "[The Cubs are] an extremely talented bunch of guys who want to look at all directions except where they should really look, and kind of make excuses for what happened," Stone said. On the final day of the season, the fans at Wrigley, sensing that he might not be back for the 2005 season (by his and/or the team’s choosing), chanted "Stoney! Stoney! Stoney!" toward the broadcast booth during the seventh-inning stretch.

But after meeting with team officials, Stone left for Arizona with the option on his contract picked up, an understanding that the dispute was over, and the intention of returning. That changed when Baker and Hendry held separate teleconferences with beat reporters a couple of days later and once again mentioned Stone. "Baker, Hendry reheat ‘feud,’" said the Chicago Tribune headline. "For me, this is over," Stone told reporter Paul Sullivan in the accompanying story. "Someone has to stop talking, so I’m going to stop talking about it." Three weeks later, he resigned.

"I think it could have been handled better on both ends," McDonough says. "It’s extremely unfortunate that it ended the way it did. In my career, it’s one of the most regrettable situations I’ve been a part of because the culmination was his departure. I wish he wouldn’t have resigned; I asked that he not. He and I spent the better part of the Saturday prior to his resignation on the phone, with me discouraging him because of what he meant to our fans."

Says Stone in retrospect: "I felt then as I feel now—no winners came out of 2004. I left something I loved, and the Cubs lost a chance to go to the playoffs and maybe the World Series. Many of the guys who were there—both in uniform and in the front office—are gone. I just don’t think anybody benefited from that particular situation. That’s the saddest part of 2004."

* * *

"Steve’s Thoughts on New [Cubs] Ownership," somewhat abbreviated, per his blog: "The [new] owner will ideally understand the psyche of the Cubs fans whose hopes have been largely unrewarded. I hope the new owners will bring Wrigley Field gracefully forward for fans’ comforts, but will preserve the historic feeling of what I consider one of baseball’s treasures. A deep unabiding [sic] love of the Cubs and Chicago would certainly help. An understanding of the Cubs’ place in baseball history is essential. The confidence and desire to bring the best baseball people available to the organization, and the intelligence to give them autonomy would be a great start."

In imagining this perfect owner, he is describing himself, of course, if unwittingly. It’s his manifesto, formulated over decades, written in less than ten minutes, succinctly articulated. (He proudly carried the handwritten original in his briefcase for days after composing it in June, reading it to friends from his legal pad and into my tape recorder, during which he made sure to stress the words "love" and "autonomy.") And yet, despite having twice before joined groups attempting to buy a major league franchise—the Oakland Athletics and Montreal Expos (now the Washington Nationals)—he says it’s unlikely that he’ll be a financial partner in any Cubs ownership deal. "I’m about $800 million short," he jokes when asked if he’s going to buy the team. But Stone would like an official post in a new owner’s front office. "The title itself means little to me," he says.

"Because of the way Steve is viewed in Chicago, it would be a great decision on the part of anybody who buys the Cubs to make him instrumental in the baseball side of the team," says Chicago businessman Lou Weisbach, Stone’s close friend and a partner in the Expos venture. "It will buy you the fans for a long time."

As of mid-August, Reuters had reported "15 credible expressions of interest" in buying the team, and Fortune named a consortium led by John Canning Jr., head of the Chicago investment firm Madison Dearborn Partners, as the early favorite. The bidding was to begin after Labor Day, and the process was expected to conclude by the end of the year. The final sale price could reach $1 billion, if it includes Wrigley Field and the Cubs’ share of Comcast SportsNet Chicago. Though he maintains he’s unaligned with any potential ownership group, Stone seems optimistic that he will find a role in the front office. John McDonough is more guarded: "As we sit right now, [Stone’s joining the front office is] something I’ve never really discussed internally with anybody. But you never say never. People have a lot of respect for Steve. It’s maybe the question that I get asked the most: Do I ever see a role in the organization for Steve? Jim Hendry is the general manager, so bringing anybody on board would be Jim’s decision." Of course, current management could change with a new owner, too, as everything about the Cubs’ future remains unknown.

Thus, Stone waits. "I would say that I’m a free agent," he explains. "I say to everybody who talks to me, ‘I will be more than happy to talk to you, and I’ll answer any question that you ask.’ Wherever it goes from there, it goes." He continues, adding emphasis: "Having been through the process [of trying to buy a team] myself, it’s long, it’s confusing, it’s dramatic; at times it can be convoluted, and at the end of the day, there’s no way to predict which direction it’s going to go in. I just have to hope that I know some of the people who are in that room on the last day, and that they view what I have to offer as valuable."

And if not? "There was a long period where I thought I would be broadcasting for the Chicago Cubs for the rest of my life," he says, "but that didn’t happen. There was a time when I thought that I would be the president of the Oakland Athletics, but that didn’t happen. There was a time when I thought I might be able to bring the Montreal Expos to Las Vegas, but that didn’t happen. Life always went on. The one thing that remains constant is that this is the city that I come to. This is where I want my baseball career to end."

* * *

Chicago, summer 2007, Al’s Beef on Ontario: Stone is about to pay for his lunch, when the owners of an air-conditioning company (one a Cubs fan, the other a White Sox fan) spot him in line. "We’re going to buy this," they tell him. The requital for a beef sandwich and hot dog: baseball discourse. So, for the next hour and 15 minutes, Stone answers whatever questions they pose. He says such afternoons seldom take place in Arizona. And that all of those who do approach share a common characteristic: "For the most part, they’re from Chicago."

Comments are closed.