“To see the most celebrated faculty member on a prestigious journalism faculty in a great university come to this kind of nasty parting with his institution—for a lot of us on the inside, it remains something of a mystery,” says a former colleague.

Related:

THE PROFESSOR AND THE PROSECUTOR »

Anita Alvarez's office turns up the heat on Protess (February 2010)

CAMPUS REVOLUTIONARY »

A look at Dean John Lavine (September 2007)

UPDATE (9/7/2011): This morning, Judge Diane Cannon of the Cook County Circuit Court ruled that the Northwestern University students in the reporting class of former professor David Protess were acting as investigators for the defense rather than as journalists, and were therefore not protected by the Illinois Reporter’s Privilege Act.

Cannon ordered that more than 500 e-mails between Protess and students who reexamined the three-decades old murder conviction of Anthony McKinney be turned over to prosecutors. The university said it is weighing its options, including a possible appeal.

The two-year legal wrangling that led to the ruling lies at the heart of the story below, which takes an in-depth look at the controversial circumstances surrounding the acrimonious departure of Protess from Northwestern and the resulting wounds that have yet to heal among many. "Loss of Innocence" appears in the October issue of Chicago, on newsstands September 15.

* * *

The image is indelible. Anthony Porter, a death row inmate who had come within 48 hours of being executed, had just walked out of Cook County jail a free man. A car was waiting to whisk him away, but before Porter could climb inside, he caught sight of a rumpled-looking, silver-haired man beaming next to a group of exultant college students. Porter ran over, threw his arms around him, and lifted the professor up, up into the raw cold of a February 1999 afternoon, until the man’s feet swung above the cracked concrete lot.

One by one, Porter repeated the act, hoisting each of the five students in turn. Shutters clicked. Cameras whirred. The moment flashed on screens across the United States and around the world, a giddy symbol of justice triumphant and yet another bragging right for the institution that the man had called his professional home for nearly two decades: Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.

It wasn’t the first time David Protess and his investigative reporting class had grabbed headlines. Three years earlier, he and his students had captured national attention by helping exonerate the Ford Heights Four—four men wrongfully convicted of murder, two of whom were on death row.

The Porter case, however, launched him and his program into the academic and journalistic stratosphere. George Ryan, then the governor of Illinois, cited Protess’s work as the driving force behind his imposition of a first-of-its-kind death penalty moratorium. “Innocence projects,” patterned on Protess’s own at Medill, sprang up across the country, filled with students and lawyers whose idealistic fervor was inspired by the Medill professor and what his class had accomplished.

In the years that followed, more exonerations would come—12 by the time Protess was done, five of which were men awaiting execution. The already estimable reputation of Northwestern’s journalism school grew with each victory. It would all end ugly, of course, in a scandal that dealt a blow to Protess’s legacy and tarnished the university. But there seemed only possibilities on that February day when Protess and his students were lifted up, up in the cold gray, against the backdrop of a jail from which another man wrongfully sentenced to die had, thanks to them, walked free.

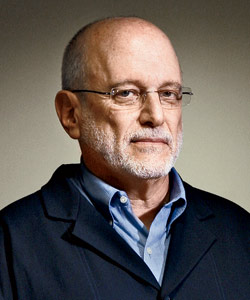

Photograph: Katrina Wittkamp

First act of freedom: Porter hugs a jubilant Protess outside Cook County jail in February 1999.

Related:

THE PROFESSOR AND THE PROSECUTOR »

Anita Alvarez's office turns up the heat on Protess (February 2010)

CAMPUS REVOLUTIONARY »

A look at Dean John Lavine (September 2007)

It was nearly impossible not to recall that image—arguably the apotheosis of Protess’s nearly 30-year career at Northwestern—when I met him at the spartan three-room suite of Loop offices that houses his new venture, the Chicago Innocence Project. The program, Protess told me when I visited in July, will be a version of what he did at Medill, the first nonprofit journalism innocence project, in fact, in the country. His work force, he says, will consist of community residents, journalists, private investigators, and, yes, students—some, he hopes, from his old stomping ground at Medill. Funding will come from grants, foundation gifts, and individual donors.

On the day I visited, Protess had only begun to move in, and the place had a barren, cheerless feel to it. A couple of volunteers, including one of Protess’s former Northwestern students, were working to spruce things up, tapping nails for hanging pictures, excavating “29 years of memories,” as Protess calls them, from cardboard boxes.

“This will be our storage area,” Protess said, gesturing at a wall. “This will be a lounge for the students. And this,” he said, “is my office.” The room was empty except for a large library desk inherited from the previous occupant and a rug donated by Protess’s son Ben, a reporter at The New York Times. On the wall hung a City Council resolution honoring Protess and his students for their work with the Ford Heights Four and a poster advertising the 1998 National Conference on Wrongful Convictions and the Death Penalty (“where it all started,” Protess says). The desk held a coffee mug, a pencil cup, a single yellow legal pad with curled-up pages, and a couple of framed family photos.

Protess insisted that his digs at Northwestern’s creaky old Fisk Hall were hardly less drab—that they were, in fact, more cramped. Still, the tableau seemed a long way from the ivied grandeur and tradition-bound corridors of the university, where for so long Protess presided as arguably the most famous professor at one of the country’s most prestigious journalism schools. “I’m in the Loop, which is a more appropriate home base for our work than the ivory tower,” Protess said. “It beats spending another year lecturing about the good old days from yellowing notes.”

The good old days came crashing to a deeply bitter end this past April, when Northwestern spokesman Alan Cubbage issued a press release that accused Protess of “numerous examples of knowingly making false and misleading statements to the dean, to University attorneys, and to others” in the case of a prisoner named Anthony McKinney.

Specifically, the release accused Protess of altering an e-mail to “hide the fact that . . . student memos had been shared with Mr. McKinney’s lawyers,” thus causing the university to unwittingly misrepresent itself in court. It also accused him of repeatedly lying about the number of documents he had shared with defense attorneys during a high-profile subpoena fight between the school and the Cook County state’s attorney, Anita Alvarez.

“Medill makes clear its values on its website, with the first value to ‘be respectful of the school, yourself and others—which includes personal and professional integrity,’” the release said. “Protess has not maintained that value, a value that is essential in teaching our students.”

On the day Cubbage issued the press release, Medill’s dean, John Lavine, held a closed-door faculty meeting to which Protess was not invited. In it, Lavine led the stunned professors through a detailed PowerPoint presentation detailing the statements contained in the release.

The allegations were shocking enough. But to many faculty members at the meeting—and, later, to students and outside observers—just as stunning was the scathing tone of the release and the public way the school’s dean had just lambasted a lauded tenured professor.

“People were horrified at that press release. They’re still horrified, and I’m still horrified,” says Donna Leff, a professor at Northwestern and one of the few faculty members willing to talk on the record about the controversy. “The way they treated David made me sick to my stomach, and I would say that even if I hated David. It was untoward.”

Both the press release and the meeting included the announcement that Protess would not be teaching in the spring. Eventually, Protess reached a negotiated settlement with the university and retired. His exit became official in September. He continues to deny the allegations that led to his downfall.

The university says it has moved on, and, indeed, Protess’s investigative reporting class and the Medill Innocence Project he founded have been turned over to Alec Klein, a former Washington Post investigative business reporter.

As a new school term gets under way at Northwestern, however, the first in nearly three decades without Protess, an essential question remains for many: “What I still don’t get is why they would allow the Babe Ruth of their school to be destroyed,” says Charles Lewis, a journalism professor at American University and founder of the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative news organization. “Or if not destroyed then impugned to such an extent that he was taken out inside their own school by the suits. It just doesn’t smell good.”

“It’s pretty perplexing,” adds Doug Foster, a Medill professor who attended the closed-door meeting. “To see the most celebrated faculty member on a prestigious journalism faculty in a great university come to this kind of bitter, rancorous, nasty parting with his institution—for a lot of us on the inside, it remains something of a mystery.”

Photograph: Heather Stone/Chicago Tribune

The Cook County state’s attorney, Anita AlvarezThe fuse that ignited the Protess powder keg sizzled to life in May 2009 when Alvarez served a sweeping and controversial subpoena on both the professor and Northwestern in the case of Anthony McKinney, a man Protess believed was wrongfully convicted of a murder some 30 years ago.

Protess’s class had been investigating the case since 2003, and by 2006 Protess felt his students had gathered enough evidence—including recantations by key witnesses who had implicated McKinney—to prove McKinney’s innocence. Accordingly, Protess authorized the sharing of certain investigative materials with the Northwestern University School of Law’s Center on Wrongful Convictions, which he had cofounded as the legal side of the Medill Innocence Project. In 2008, defense attorneys filed a petition asking that McKinney’s conviction be overturned.

When the case landed in the lap of Alvarez, defense attorneys at the Center on Wrongful Convictions hoped that she might agree that McKinney should be freed. Instead, she turned the tables and issued a subpoena targeting Protess and his students. Among the materials she sought were student memos, notes, syllabuses, reports, teacher evaluations, and grades. (To learn more about that confrontation, read “The Professor and the Prosecutor,” from February 2010.)

Related:

THE PROFESSOR AND THE PROSECUTOR »

Anita Alvarez's office turns up the heat on Protess (February 2010)

CAMPUS REVOLUTIONARY »

A look at Dean John Lavine (September 2007)

The battle exploded in the media. With Northwestern’s backing, Protess refused—loudly and publicly—to comply with the subpoena, asking what the information had to do with McKinney’s guilt or innocence and questioning Alvarez’s motives. The university hired the high-powered law firm Sidley Austin to argue that the materials were protected by the Illinois Reporter’s Privilege Act and federal privacy laws. Also rising to Protess’s defense were a number of media and academic heavy hitters, who wondered aloud whether the state’s attorney was seeking justice or trying to take down a professor and a project that for years had embarrassed the office and cost Cook County millions in settlement payouts.

Alvarez hit back, saying the sole reason for her subpoena was that two witnesses who had recanted had accused Protess’s students of questionable reporting tactics. Among the allegations—all called absurd by Protess and his class—were claims that female students had flirted to get information, that the students had told the witnesses they’d get better grades if the men recanted, and, in one case, that a student had paid a witness to change his story.

In the beginning, the university—including Lavine—rallied behind Protess. Medill’s dean even promised that he would “go to jail” with Protess rather than capitulate to Alvarez’s demands. As the months wore on, Lavine continued his support, praising the work of the star professor and pillorying the state’s attorney’s effort to compel production of the materials (“I think it is dead wrong,” Lavine told me in an interview in early 2010).

* * *

Photograph: Michael Tercha/Chicago Tribune

John LavineThen, starting in September 2009, a fissure began to separate Protess from the university’s lawyers and—ultimately and ominously—Lavine. That month, a defense attorney from the Center on Wrongful Convictions, Karen Daniel, privately told the university that she had discovered that a “significant amount” of material had been turned over to her by Protess as his class’s investigation of the McKinney case had unfolded. The information included something the state’s attorney’s office was particularly interested in: student memos about their witness interviews.

It was an unsettling revelation for the school and for Protess. Anything he and the project shared with the defense attorneys likely would not be protected under the Illinois press shield law.

Thus the university’s lawyers needed to be certain of what had been turned over to the Center on Wrongful Convictions so that they could shape their strategy in the increasingly expensive, increasingly high-stakes subpoena battle.

But rather than relying on what Daniel said she had in hand, the lawyers turned to Protess. From the beginning, however, he expressed concerns over his memory. In a September 2009 e-mail exchange with a university lawyer, he said “it had been several years” since the project had shared the materials with the center, and he “couldn’t remember” their exact contents. Complicating matters, he adds, was the fact that his wife, Joan, had been sick with breast cancer at the time of the McKinney case.

Related:

THE PROFESSOR AND THE PROSECUTOR »

Anita Alvarez's office turns up the heat on Protess (February 2010)

CAMPUS REVOLUTIONARY »

A look at Dean John Lavine (September 2007)

Today Protess readily admits that his memory not only failed—it failed “miserably.” It turned out Daniel was right: He had given the center more materials than he thought. Protess says he compounded the problem by stubbornly sticking to his faulty recollection. “I should not have gotten so defensive when [Daniel] took a position contrary to mine,” he says. “That’s on me. The analogy I would draw is to spouses in a bitter fight. The longer the disagreement over an issue, the more each side stubbornly sticks to his or her position, regardless of the facts.”

Still, Protess says, he was willing to try to settle the matter. At a December 2009 meeting with Lavine and the university’s lawyers, Protess says he threw out an idea: Since his method of sharing memos and documents with defense attorneys was mostly via e-mail, couldn’t the university simply search his e-mail accounts and find out, once and for all, exactly what he had turned over? He says he was told no. He asked if there was any other way. There was, he says he was told, but it would be “prohibitively expensive.” (Without addressing specifics of what was discussed in the meeting, Cubbage, who was not present, called Protess’s account “categorically false.”)

Over the next few months, the university continued to rely on Protess’s representations as it fought the Alvarez subpoena. Then, at a hearing before Judge Diane Cannon in circuit court on June 24, 2010, Daniel dropped a bombshell: She admitted in court what she had told Northwestern’s lawyers in September 2009—that she had indeed received a large amount of evidence from Protess, far more than he had been telling the university. Included in the evidence were student memos of witness interviews, the same memos Medill’s lawyers had been arguing were protected by the shield law.

The revelation was deeply embarrassing to the university’s lawyers and, by extension, to Lavine and Medill. For months, based on Protess’s incorrect representations, school attorneys had, however unintentionally, been misleading the court.

The university—Lavine in particular—was furious. In time, the dean would accuse Protess of knowingly and intentionally lying about what he had turned over to the center.

Lavine, who declined to comment for this story, based the accusations on hundreds of pages of e-mails that were recovered when university lawyers finally took the step that Protess says he had been told eight months earlier was prohibitively expensive: The school conducted a forensic analysis of Protess’s home and work computers.

The recovered e-mails showed, according to the university, several exchanges between Protess and the center in 2005 and 2006 that repeatedly contradicted the professor’s frequent claim that he never shared unpublished student memos with defense attorneys.

The proof that Protess was lying about the memos, according to the university, was in an e-mail that he had sent to his assistant, Rebekah Wanger, in November 2007. In the original e-mail, Protess said, “My position about memos, as you know, is that we share everything with the legal team and don’t keep copies—except when I want to use them to refresh my memory for something I plan to write about a case.” The altered version read simply, “My position about memos, as you know, is that we don’t keep copies.”

To Lavine and the university, that discovery clearly showed that Protess was lying to cover up that he had in fact turned over student memos—the most sought-after evidence by Alvarez—to keep from having to share them with prosecutors.

For his part, Protess has admitted changing the e-mail. But he has insisted throughout the controversy that he did so not to mislead but to more accurately represent his practices. “I was mistaken in saying we share everything with the legal team,” he says. “We don’t share everything. I never did share everything with the center.” Moreover, Protess points out, when he wrote the e-mail, he was speaking informally with an assistant, not realizing at the time that lawyers would later take it as gospel.

He may have turned over numerous student memos, Protess says, but he didn’t share all of them. “I [also] didn’t share things that were class work. I didn’t share things that invaded my students’ privacy or hurt their reputations.” A June 27 court filing by Daniel herself seems to corroborate Protess’s claim. In it, Daniel says that she never received—or has no recollection of receiving—notes or audio recordings made by students at witness interviews, evidence which was sought by prosecutors.

Meanwhile, an October 2010 letter from the university’s general counsel seemed to acknowledge Protess’s memory explanation. “I recognize that it is often difficult to recall fully and accurately matters that occurred several years ago,” Thomas G. Cline wrote in an e-mail to Protess and Lavine. “It now appears . . . that some of your statements and recollections regarding materials published to the Center may not have been completely accurate.”

The far larger issue, Protess argues—the very heart of the case against him, he says—is the failure of the university to perform the forensic audit either when the conflict first arose between him and Daniel in September 2009 or later, in December of that year, when he says he was told that the procedure was too expensive. Had university lawyers searched his computers in the beginning—rather than waiting until July—the entire controversy could have been avoided, according to Protess. When asked why the university chose to rely on Protess over Daniel, Cubbage declined to comment.

Instead, by the fall of 2010, the fissure had widened into a chasm. Over Protess’s objections, the university, with a growing PR embarrassment on its hands, began to relent in the subpoena fight and started turning over thousands of student documents to the state’s attorney’s office.

Protess, saying he no longer believed his best interests were being represented by Richard O’Brien, the university’s lead attorney, hired his own lawyer. “That would seal my fate,” he says. Within days, O’Brien withdrew from the case, telling Protess in an e-mail, “We believe that you have displayed a lack of candor with us and have not cooperated with us.”

The university replaced O’Brien with three former prosecutors who worked at Jenner & Block, including Anton Valukas, a former U.S. attorney and a Northwestern law school alumnus. (Valukas did not respond to a request for an interview.)

The battle lines were drawn. In late October 2010, Valukas sent Protess’s new lawyer a letter announcing that he was launching a thorough review of Protess, his class, and the Medill Innocence Project.

Suddenly what had once been a high-profile fight between the state’s attorney and the star professor had become a very different clash of titans: Lavine and Protess. It was not the first time the two men had tangled.

* * *

Photograph: Anna KnotT

Related:

THE PROFESSOR AND THE PROSECUTOR »

Anita Alvarez's office turns up the heat on Protess (February 2010)

CAMPUS REVOLUTIONARY »

A look at Dean John Lavine (September 2007)

Though both were heavyweights at Northwestern, their confrontation seemed—on the surface at least—an unlikely fight card. In one corner was David Protess, the highly respected professor who “literally saved the lives of innocent men who had been wrongly locked up in prison and essentially given up for dead,” says Mark Feldstein, a journalism professor at the University of Maryland. “What other journalism professor at any other university has made such a crucial impact?”

American University’s Lewis puts it more succinctly: “You’re talking about Mount Rushmore here.”

It was true that there were grumblings. Protess, some said, could be aggressive, defensive, even bullying—and not above pushing ethical boundaries when it came to reporting techniques and methods. Questions had been raised about his investigative journalism class before—namely, whether his students were acting as reporters or advocates. “It was always kind of fuzzy whether he was engaged in journalism or a kind of guerrilla social justice law operation where the ends justified the means,” Michael Janeway, the Medill dean from 1989 to 1996, told The New York Times in June. “David was not totally irresponsible. He was a zealot in pursuit of a cause, a cause you could not question.” (Janeway declined to comment for this story.)

Maurice Possley, a Pulitzer Prize winner and former reporter for the Chicago Tribune who has written about cases in which Protess and his students were involved, says Protess has “always been incredibly professional in all my interactions with him.” But Possley adds: “If I ever had a concern from my vantage point as a journalist, it was that there seemed to be a little too much advocacy for a program whose purpose was to teach students how to investigate criminal cases in an unbiased and detached fashion. But I wasn’t in the classroom or at the lectures. That’s a perception.”

Others—who have made it clear that they’re not commenting on the current allegations against Protess—defend him and his work. “During my tenure as dean, there was never a question that Protess was doing anything that defied journalistic ethics,” recalls Ken Bode, dean of Medill from 1998 to 2003. He says that in light of the subpoena fight, “there arises the notion that we should have monitored his activities more closely. But, as I said, we had no reason to think he was doing anything wrong. Nor is there any evidence that he was.”

In the other corner was John Lavine. “At 66, Lavine looks the part of a grisly desk editor at a big-city newspaper,” Dirk Johnson wrote in an article in Chicago in 2007. “Bald, stubbly beard, rimless glasses, and no shortage of attitude. He comes off as exceedingly bright and just as cocksure.” Indeed, when he arrived in 2006, Lavine promptly caused a stir by declaring that he planned to “blow up” the Medill curriculum. His contention, prescient in retrospect, was that budding journalists needed to become versed in new media, such as the Internet, videos, and podcasts. They also needed to learn the tools of marketing, he said, to help better “involve and engage” audiences.

Lavine’s proposed new direction, and the speed with which he sought to implement his vision, caused a furor. While conceding his points generally, Lavine’s critics protested that the radical changes were coming at the expense of the bedrock journalistic principles—namely, writing and reporting—upon which Medill’s reputation had been built.

Among those who expressed concern was Protess. Though he agreed that the changes were necessary, he says, he was deeply concerned that the faculty was not being allowed input and was dismayed at what he perceived as a threat to traditional journalistic values. In a move that almost certainly did not escape the dean’s attention, Protess organized the faculty to demand a vote on the new curriculum. (The motion failed in an 18–18 tie.)

* * *

Still, whatever tensions might have existed behind the scenes, in front of the curtain the two men seemed to enjoy a good relationship both personally and professionally. The dean publicly praised Protess’s work and lent critical support in grant applications.

Then, in the spring of 2008, Lavine found himself embroiled in his own scandal. Quotegate, as it came to be known, came to light in the form of a story in the student newspaper, The Daily Northwestern, by David Spett, a Medill senior. Specifically, Lavine was accused of fabricating anonymous quotes in a column for Medill’s alumni magazine. One column, which touted Lavine’s new curriculum, included a quote, supposedly from a Medill junior, that struck Spett as odd: “I sure felt good about this class. It’s one of the best I’ve taken.” After determining the class to which Lavine was referring, Spett tracked down all 29 students enrolled in it. Each one denied giving the quote.

That the controversy erupted in both the local and national media came as no surprise: The dean of one of the nation’s top journalism schools was being accused of violating a core ethical rule of the craft. Some 240 students and faculty signed a petition expressing their concerns. The Chicago Tribune reporter Eric Zorn hammered Lavine in a series of columns, including one that said Lavine should produce his sources or resign. “The way Northwestern has handled this issue has transformed a somewhat embarrassing little incident into a full-blown disgrace that has tarnished the reputation not only of Medill but of the entire university,” Zorn wrote.

Spett was the face of the controversy, but Protess also played a highly public role. When Spett’s reporting came under fire, Protess tracked down the five juniors in the class and, like Spett, could not find any who admitted uttering the quote in question. Protess’s efforts were detailed in a February 27 blog post by Zorn. Protess then sponsored a faculty motion—signed by 14 other professors—calling for Lavine to reveal the source of the quote. Lavine said he could not find his notes or e-mails to back his story. Eventually, he issued a statement denying he had made up the quote but apologizing for his “poor judgment” in using an unnamed source.

What has not been reported is that the original source for Spett’s column was Protess himself. Protess says he became suspicious when he read the quote Lavine had attributed to the unnamed student. A phrase in that quote—“sure felt good”—reminded him of an e-mail he had received from Lavine several months earlier congratulating him on yet another exoneration. In it, the dean used the words “sure felt good,” Protess says.

Northwestern’s provost, Daniel Linzer, appointed a committee of three members of the Medill board of advisers to investigate. Lavine was cleared, but the episode cast a pall over the proud school. “You would have to be under a rock somewhere not to get that it was an extremely embarrassing situation for the journalism school,” says Donna Leff, the Medill professor.

* * *

Related:

THE PROFESSOR AND THE PROSECUTOR »

Anita Alvarez's office turns up the heat on Protess (February 2010)

CAMPUS REVOLUTIONARY »

A look at Dean John Lavine (September 2007)

Given his prominent role in the indignities visited on Lavine, Protess says he found it odd when, a few weeks after the controversy’s resolution, in the spring of 2008, Lavine approached him with an idea for a project. The dean told Protess that he wanted to assign a junior faculty member, Eric Ferkenhoff, to shadow Protess and write a report about his teaching methods. The form the report would take was as yet unclear—perhaps it would be a chapter in a book, an article in an academic journal, or even a feature story—but the motive was simple, as university spokesman Alan Cubbage told me later in an e-mail: to help “other faculty and reporters covering wrongfully convicted cases . . . understand what the Medill Innocence Project did.”

Protess agreed, he says, on the stipulation that he be allowed to review the report and comment on it before it was turned in. Ferkenhoff began showing up in class, attending periodically for several months.

According to Protess and other sources, however, in August 2010—two years after he had begun working on the report and in the midst of the subpoena contretemps with Anita Alvarez—Ferkenhoff began to express concern over the purpose of the project. Specifically, Protess and others say, Ferkenhoff told them he was worried that he was being “used” to hurt Protess, something he did not want to do. (Ferkenhoff declined to comment for this article.)

Protess says that he meanwhile began receiving calls from students and colleagues saying that Ferkenhoff was asking them about allegedly questionable reporting practices in Protess’s class. At some point, the report was abruptly submitted while still in draft form.

When questioned later by the university’s lawyers from Jenner & Block, Protess says, he recognized some of the queries. They were the same ones that had been raised in the calls from his students. Sources say the lawyers from Jenner also questioned Ferkenhoff at length.

On March 11, Protess’s lawyer, Randall Gold, sent a letter to Jenner & Block accusing the university and Lavine of using Ferkenhoff to “[gather] dirt on Professor Protess for a nefarious purpose.” Three days later, Anton Valukas sent Gold a one-sentence e-mail: “As we discussed, the Dean has determined that David Protess will no longer be assigned to teach Medill’s Investigative Reporting class in the 2011 spring quarter.”

The news spread quickly, followed by a fresh uproar. Nearly 400 students and alumni signed a petition demanding that Lavine provide a “public explanation of the facts surrounding the apparent removal of Professor Protess.” The American Association of University Professors also demanded to know Lavine’s reasoning. Students who had signed up for Protess’s class and students who had just taken the course signed petitions asking Lavine to reconsider.

With pressure mounting on the university to provide an explanation, Lavine called a closed-door faculty meeting, and on April 6 a group of professors filed into Fisk Hall. The teachers assumed the main subject would be Protess. Beyond that, however, “there was a lot of mystery and curiosity,” recalls Donna Leff. Daniel Linzer, who had presided over the Quotegate investigation, also attended.

Lavine wasted little time. He launched a PowerPoint presentation that he said showed in no uncertain terms that Protess had intentionally misled the university and exposed it to potential legal problems in the subpoena fight. “There was definitely a focus on ‘This e-mail was doctored. See? This is how he altered this e-mail,’” recalls Leff.

The 30 to 40 faculty members in attendance were shocked—at both the tone and tenor of the presentation as well as the allegations. “People were sort of going, ‘Uh-oh, what is this?’” Leff recalls. “But then as it went on and people asked questions, there started to be a feeling of, Is this all there is? I mean, there was one e-mail, just one altered e-mail among what must have been thousands of pages of e-mails. The connected dots weren’t persuasive. I thought, OK, your gut instinct was right. This was not about fairness. This is not an attempt to get at the truth. This is an attempt to smear David. And you know what? They successfully smeared him.”

Not everyone agrees with Leff. Several professors found Lavine’s presentation deeply persuasive, sources say. (Chicago made repeated, ultimately unsuccessful attempts to persuade such professors to comment for the record or even for background.) “There was a significant minority who I think came away from that session saying, ‘Boy, it’s lucky that the dean and the provost are doing what they’re doing, because there’s a problem with this colleague in our midst,’” says Doug Foster, who spoke with several faculty members afterward. “And I think in the aftermath of it, and [with] David being gone, there probably are more people who have begun to think, Well, there must have been more to it than we even knew, and so the institution is probably better off.”

By meeting’s end, two votes were taken asking that Protess be brought in and given a chance to respond to the allegations, with a majority voting in favor both times. They did so “despite the fact that they knew their jobs could be on the line for opposing this administration,” says Leff. “It was brave of people. . . . [Instead] we were told in a very sort of patronizing manner that we can’t invite David, and we can’t discuss this more openly because our lawyers won’t let us.”

“To their credit,” Foster adds, “the dean and the provost came to us. We’d been asking for an explanation. . . . [But] obviously our colleague wasn’t there to give the other side. It seemed quite one-sided.” When I asked Alan Cubbage why Protess wasn’t allowed to attend, the spokesman responded by e-mail: “Professor Protess was on leave spring quarter. Faculty members on leave do not attend faculty meetings.” A member of the faculty senate, however, says he finds the explanation to be a “pretty flimsy rationale. I certainly have never heard of faculty leave being used as a basis for barring a faculty member from attending a faculty meeting.”

What further rankled certain teachers was the fact that the very afternoon the closed-door meeting was being held, Cubbage was issuing a press release that repeated the charges they’d just heard, supposedly in private. “It’s just not what you do,” Leff says.

Foster agrees. “That the university had seen fit to issue a one-sided, nasty, vituperative broadside against him in the form of that press release seemed to be a violation of trust, not only of the university’s relationship with David Protess as a faculty member but a breach of trust with us.”

Cubbage responds by saying that Protess forced the university’s hand. “Northwestern University generally does not discuss publicly actions regarding its faculty and staff,” he says in an e-mail. “However, statements in the media by Professor Protess and our desire to be as forthcoming as possible on an issue of great importance to the University, its faculty, our students, alumni and our community prompted us to make the statement.”

* * *

Related:

THE PROFESSOR AND THE PROSECUTOR »

Anita Alvarez's office turns up the heat on Protess (February 2010)

CAMPUS REVOLUTIONARY »

A look at Dean John Lavine (September 2007)

A few weeks later, an article by a Medill senior, Brian Rosenthal, appeared in The Daily Northwestern, questioning the reporting methods of Protess and his students. On the same day, a lengthy piece in the Chicago Tribune raised similar questions. Both articles cited two identical episodes (neither of them denied by Protess): that one of his students said she had misrepresented herself as a U.S. Census Bureau employee to learn the whereabouts of a potential source and that another had posed as a ComEd worker to help track down a witness.

Both incidents were contained in the Ferkenhoff report, according to sources. And Protess says Jenner & Block questioned him about both. When I asked Cubbage whether the report had been leaked, he responded, “The University has no knowledge as to whether the report was shared, other than it was not shared by the University’s Office of General Counsel or its outside counsel.” Rosenthal told me that he “had no direct contact with the so-called report.” The Tribune reporter, Matthew Walberg, declined to comment.

The stories could merely have been the result of increased scrutiny brought on by the controversy over Protess and the nature of the accusations against him. Whatever the case, the effect was palpable. Protess’s reputation, as well as his 30-year legacy, suffered a staggering blow. More than that, media attention had shifted away from outrage over Protess’s ouster and onto his and his students’ professional ethics.

Protess offered his defense: There’s a long tradition of reporters going undercover, including for a Pulitzer Prize–winning series in the Tribune in which the reporter William Gaines posed as a janitor to detail hospital abuses.

And several practitioners back him up. “As a longtime investigative reporter who also holds a doctorate and specializes in the history of investigative journalism, I can tell you this,” says the University of Maryland’s Feldstein: “Exposing wrongdoing is not easy. Powerful interests do everything they can to block such challenges to their authority. I can tell you that flirting with a source or paying a source’s cab fare is a routine practice among journalistic professionals, not even a misdemeanor compared to the literal felonies that Protess exposed.”

Others disagree with the practice of journalists misrepresenting themselves. “I don’t say I condone that, and it’s not what I do as a journalist,” says American University’s Lewis. “I always disclose who I am, and that’s how I conduct myself. [But] I also understand that this is a slightly gray area.” In the end, the point was moot. Protess was out. The damage was done—both to him and to the school. “It has a long-term effect that will take a long time for the institution to get over,” says Foster. “It’s one of those moments in the 90-year history of Medill, one of those chapters in the [university’s] history, that I think will remain heartbreaking.”

Not just heartbreaking, adds Leff. Ironic. “From the minute I heard about the Anita Alvarez subpoena, I felt that she set out to ruin David’s reputation and to derail the concept of the [Medill Innocence] Project. And I think she did a damn good job. And I think that, wittingly or unwittingly, the university played right into her hands.”

At the bottom of it all, the question still remains: Why would the university go to such great lengths to not simply reprimand Protess—or even push him out—but to publicly attack him, his work, and his integrity, to virtually excommunicate a man who had brought such renown to the school?

The university’s leaders would say their actions were fully appropriate and justified given the seriousness of Protess’s alleged behavior and the damage they say his actions caused to the school. When I asked Cubbage whether the university had any regrets over how things ended, he answered flatly, “No.”

Protess has his own theory, of course. He was, simply put, a scapegoat. The university’s lawyers, he asserts, made a terrible mistake when they did not immediately perform a search of his computers. That error wound up humiliating them and the school itself when they had to admit that much more material had been shared with the defense than they had been insisting in court. It was easier to throw him under the bus, Protess argues, than to allow blame to fall on the school. “This is what powerful institutions do when you cross them,” he says.

* * *

On April 11, Protess told Lavine that he planned to come to his office to pick up his mail, water his plants, and return phone calls. The dean, he says, wrote back to him, saying, in effect, not to bother. Instead, Lavine told the celebrated professor—the man who had spent nearly half of his 65 years teaching at the university and who, under the aegis of Northwestern’s journalism school, had almost single-handedly ended the death penalty in Illinois—that “he would have my mail forwarded,” Protess says, “have someone water my plants—and [I could] retrieve my messages from home.”

* * *

In July, in the barren offices of the Chicago Innocence Project, Protess was putting the final touches on the case of Stanley Wrice, a 56-year-old man who is serving 100 years in prison for a 1982 sexual assault he says he did not commit. Wrice claims he was forced to confess to the crime by officers working for Jon Burge, the former Chicago police detective who allegedly tortured more than 200 suspects.

Around Protess bustled a former Northwestern student, a high schooler, and his lone paid staffer, a man named Eric Caine, who—thanks largely to Protess and his students—was freed from prison last March after 25 years of wrongful incarceration.

Protess says he will continue to cheer efforts to free Anthony McKinney, the prisoner whose case in a roundabout way triggered his downfall at Northwestern. McKinney’s fate now rests in the hands of the Cook County circuit judge Diane Cannon—as does the final decision regarding the subpoena case involving Protess’s former students. At presstime, Cannon said she would rule in September on whether Protess’s students were working as journalists or as investigators for the defense.

As Protess and I talked, an el train rumbled past the window of his new digs. “I like that,” he told me. “It has a nice feel.”

I asked if he was bitter. “I feel a great deal of sadness over the way it ended,” he said. “I feel sadness about my colleagues who I’m leaving behind. I feel bad personally that I won’t be able to work with the most extraordinary students there are in this country.”

But then he said, “I probably wouldn’t have left and started this project if the unfortunate events hadn’t happened. When you do anything for 29 years, it often takes a shock to the system to be able to do something new.”

As he talked, one of his volunteers popped her head in. “We just wanted to know if we could start hanging things on the walls,” she said. Protess laughed and nodded. “OK.”