Convicted of murder at 22 after a botched 1953 robbery of a Chicago meatpacking plant left a security guard dead, Paul Crump wrote the novel Burn, Killer, Burn while on death row. He became a celebrity, befriended by Gwendolyn Brooks and a young William Friedkin (who later directed The Exorcist). The latter made the documentary The People vs. Paul Crump, in which Crump asserted his innocence and detailed abuse at the hands of police. Governor Otto Kerner saw the film and, in 1962, 35 hours before Crump was to be executed, commuted his sentence to 199 years in prison without parole. At the time, Crump was the only prisoner in the state ineligible for parole; that provision was dropped in 1976. Crump, who eventually admitted his guilt, saw his appeals for release denied repeatedly, as Alfredo S. Lanier detailed in the 1983 Chicago article “A Lifetime of Waiting.”

Ironically, although all of this relentless publicity has saved Crump from the electric chair, it has also kept him in jail. His notoriety has long ceased to have any connection with the actual crime; as many of his supporters now observe, Crump would have been a free man many years ago had he been an anonymous murder convict.

Crump was paroled in 1993. Six years later, reportedly struggling with paranoid schizophrenia, he piled garbage outside his sister’s door and locked her out of her house, which violated an order of protection she had against him. A Cook County Circuit Court judge determined that Crump needed to be held in a mental health center downstate, where he remained until his death in 2002 at age 72.

Read the full story below.

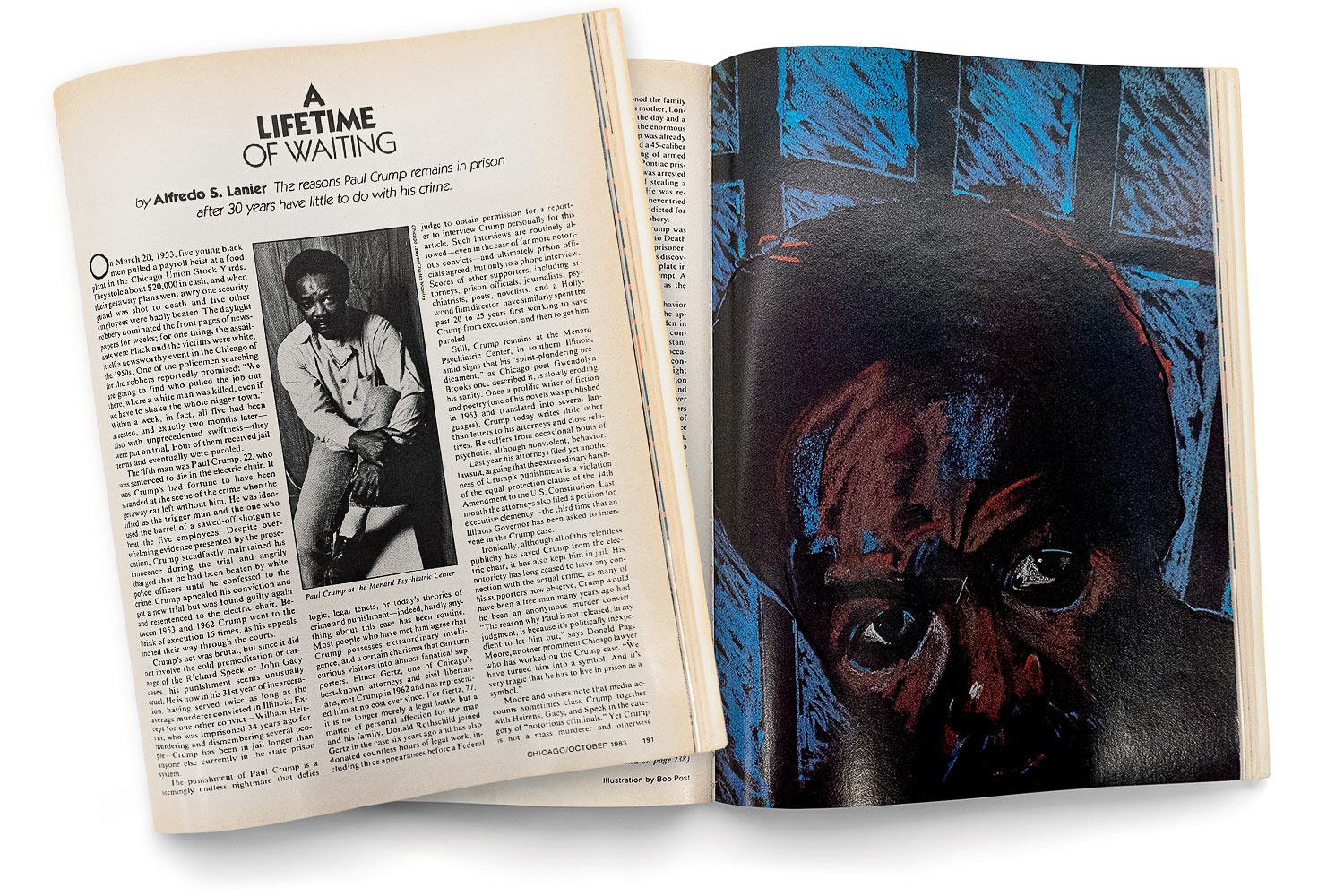

A Lifetime of Waiting

The reasons Paul Crump remains in prison after 30 years have little to do with his crime.

On March 20, 1953, five young black men pulled a payroll heist at a food plant in the Chicago Union Stock Yards. They stole about $20,000 in cash, and when their getaway plans went awry one security guard was shot to death and five other employees were badly beaten. The daylight robbery dominated the front pages of newspapers for weeks; for one thing, the assailants were black and the victims were white, itself a newsworthy event in the Chicago of the 1950s. One of the policemen searching for the robbers reportedly promised: “We are going to find who pulled the job out there, where a white man was killed, even if we have to shake the whole nigger town.” Within a week, in fact, all five had been arrested, and exactly two months later — also with unprecedented swiftness — they were put on trial. Four of them received jail terms and eventually were paroled.

The fifth man was Paul Crump, 22, who was sentenced to die in the electric chair. It was Crump’s bad fortune to have been stranded at the scene of the crime when the getaway car left without him. He was identified as the trigger man and the one who used the barrel of a sawed-off shotgun to beat the five employees. Despite overwhelming evidence presented by the prosecution, Crump steadfastly maintained his innocence during the trial and angrily charged that he had been beaten by white police officers until he confessed to the crime. Crump appealed his conviction and got a new trial but was found guilty again and resentenced to the electric chair. Between 1953 and 1962 Crump went to the brink of execution 15 times, as his appeals inched their way through the courts.

Crump’s act was brutal, but since it did not involve the cold premeditation or carnage of the Richard Speck or John Gacy cases, his punishment seems unusually cruel. He is now in his 31st year of incarceration, having served twice as long as the average murderer convicted in Illinois. Except for one other convict — William Heirens, who was imprisoned 34 years ago for murdering and dismembering several people — Crump has been in jail longer than anyone else currently in the state prison system.

The punishment of Paul Crump is a seemingly endless nightmare that defies logic, legal tenets, or today’s theories of crime and punishment — indeed, hardly anything about this case has been routine. Most people who have met him agree that Crump possesses extraordinary intelligence, and a certain charisma that can turn curious visitors into almost fanatical supporters. Elmer Gertz, one of Chicago’s best-known attorneys and civil libertarians, met Crump in 1962 and has represented him at no cost ever since. For Gertz, 77, it is no longer merely a legal battle but a matter of personal affection for the man and his family. Donald Rothschild joined Gertz in the case six years ago and has also donated countless hours of legal work, including three appearances before a Federal judge to obtain permission for a reporter to interview Crump personally for this article. Such interviews are routinely allowed — even in the case of far more notorious convicts — and ultimately prison officials agreed, but only to a phone interview.

Scores of other supporters, including attorneys, prison officials, journalists, psychiatrists, poets, novelists, and a Hollywood film director, have similarly spent the past 20 to 25 years first working to save Crump from execution, and then to get him paroled.

Still, Crump remains at the Menard Psychiatric Center, in southern Illinois, amid signs that his “spirit-plundering predicament,” as Chicago poet Gwendolyn Brooks once described it, is slowly eroding his sanity. Once a prolific writer of fiction and poetry (one of his novels was published in 1963 and translated into several languages), Crump today writes little other than letters to his attorneys and close relatives. He suffers from occasional bouts of psychotic, although nonviolent, behavior.

Last year his attorneys filed yet another lawsuit, arguing that the extraordinary harshness of Crump’s punishment is a violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Last month the attorneys also filed a petition for executive clemency — the third time that an Illinois Governor has been asked to intervene in the Crump case.

Ironically, although all of this relentless publicity has saved Crump from the electric chair, it has also kept him in jail. His notoriety has long ceased to have any connection with the actual crime; as many of his supporters now observe, Crump would have been a free man many years ago had he been an anonymous murder convict. “The reason why Paul is not released, in my judgment, is because it’s politically inexpedient to let him out,” says Donald Page Moore, another prominent Chicago lawyer who has worked on the Crump case. “We have turned him into a symbol. And it’s very tragic that he has to live in prison as a symbol.”

Moore and others note that media accounts sometimes class Crump together with Heirens, Gacy, and Speck in the category of “notorious criminals.” Yet Crump is not a mass murderer and otherwise shares little with these other prisoners — except for the massive publicity surrounding his case.

An unlucky coincidence has made the Crump case even more politically sensitive. During the 1962 clemency hearings that resulted in the commutation of Crump’s death sentence, a young state’s attorney named James R. Thompson argued that Crump should be executed. Now, as Governor, Thompson appoints the members of the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, who in turn will decide when, if ever, Paul Crump will be paroled.

Elmer Gertz and his partner on the case, Donald Rothschild, have no direct proof that Thompson has ever pressured board members not to release Crump and neither the members of the parole board nor the Governor would comment. Gertz, however, explains that the 1962 Crump hearings were Thompson’s first important and well-publicized case as state’s attorney, and that his present position as Governor cannot help but hurt Crump’s chances for parole. Their most recent executive clemency petition is intended to “smoke out” Governor Thompson and force him to take a public position, according to Rothschild. However, attorney Donald Moore doubts that Thompson, a supporter of the death penalty and a conservative in law-and-order issues, would free Crump. “He would say no, and issue a very popular statement [on law and order],” says Moore. “It would be a coherent, logical statement, and it would sell. And it would all be political.” Being tough on criminals, especially those known to the voting public, has always been good politics.

The 1962 commutation hearings, in which Thompson participated, became one of the biggest media and legal events in recent history. People were riveted to the high-stakes courtroom drama. By that time, the defense lawyers had exhausted every other legal recourse, including appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court, and Crump’s only hope of beating the electric chair was to persuade the parole board to recommend commutation.

The media were also attracted by the array of celebrities, including criminal lawyer Louis Nizer, who defended Crump. Priests, rabbis, psychiatrists, sociologists, penologists, and, most notably, prison officials also testified on Crump’s behalf. In all, 57 witnesses argued against his execution. While protesters solemnly picketed outside the courtroom, elsewhere in the country various national figures, from Billy Graham to Mahalia Jackson, made public pleas. During a recess, Father James Garrard Jones, the Episcopal chaplain at Cook County Jail, exclaimed, “My God, we’ve practically canonized the guy!”

The hearings marked the first time the Governor had been asked to spare a Death Row prisoner on the grounds of rehabilitation. The novel argument was sure to be met with skepticism by the parole board. To avoid the electric chair, common wisdom dictated, a convict would do or say just about anything; as one observer said, “Everyone gets religion on Death Row.” In addition, if this approach proved successful the other dozen or so men at the Cook County Jail awaiting their date with “Old Smoky,” as the electric chair was nicknamed, might try a similar tactic.

For Paul Crump, rehabilitation would have been little short of a miracle, because his background reflected the typical trajectory of a ghetto kid who had dabbled in petty thievery as a youngster and then became a habitual criminal by the time he reached 20.

Crump was born in Morgan Park, a community on the South Side. He was one of 13 children. His father abandoned the family when Crump was five. and his mother, Lonie, worked as a maid during the day and a laundress at night to support the enormous household. At age ten, Crump was already stealing bicycles. At 16, he used a 45-caliber revolver to pull his first string of armed robberies; they landed him in Pontiac prison. Shortly after his release he was arrested for breaking into a home and stealing a shotgun. By now he was 22. He was released on bond, but the case was never tried because, within a year, he was indicted for the Stock Yards murder and robbery.

At the Cook County Jail, Crump was the youngest man ever to be sent to Death Row. He was not exactly a model prisoner. Six months after his arrival, guards discovered that he had sawed off a steel plate in his cell, in an apparent escape attempt. A year after that, he was identified as the ringleader of a major jail riot.

The turnaround in Crump’s behavior came gradually, but it began with the appointment of Jack Johnson as warden in 1955. Johnson found deplorable conditions at the jail and a nearly constant state of prisoner unrest, including occasional riots. Reasoning that improved conditions and more humane treatment might quiet things, Johnson ended the tradition of segregating the men on Death Row and of chaining their hands and feet whenever they stepped out of their cells. Prisoners were allowed two visits a month instead of one, and they could now write letters three times a week instead of once a month. Johnson also began assigning inmates to various work details inside the jail.

Johnson’s enlightened approach made a particularly significant impact on Crump, who worked as a practical nurse in the infirmary ward. There he met Eddie Balchowsky, a crippled beatnik artist who was in for a petty offense. Crump recalls Balchowsky as an oddball, with little in common with others, yet they became close friends. “We had conversations long into the night,” says Crump. “Eddie was the first contact I ever had with any kind of cultural or creative thinking.” Balchowsky knew Nelson Algren, who visited him regularly, and suggested that Crump read Algren’s The Man with the Golden Arm. Crump excitedly read the work and later met Algren. The meeting was somewhat of an epiphany for Crump: “Up to then all I had thought about was death, death, death. I had committed this crime, the law provides that I should die, and I had accepted it. But then I started thinking that maybe it wasn’t right for me to die.” Through Algren, Crump contacted another author, Felix Singer, who encouraged Crump to start writing. Singer also discussed Crump’s predicament with Lois Weisberg, until recently the executive director of the Chicago Council of Lawyers. (She recently was appointed as the director of the Mayor’s Office of Special Events.) At that time, Weisberg was known mainly as the publisher of The Paper, a small, eclectic publication covering everything from poetry to jazz. (“We had a very strange list of subscribers and contributors,” Weisberg recalls. “It could be anybody from a truck driver to a writer for The New York Times.”)

Hans Mattick, then the assistant warden, also took a keen interest, and, despite Crump’s initial hostility, chaplain Jones developed a growing admiration for him. “I was impressed by his sense of manhood,” Jones says. “He had decided that he was not going to go to the electric chair whimpering. He was going to fight until the first jolt of electricity went through him. Paul also developed an ability to transcend the smallness of the prison walls and see the bigger gestalt, to look at life as a whole and at the same time to re-examine his own life and develop a willingness to grow.”

Mattick, who later became a professor at the University of Chicago, introduced Crump to Moby Dick and asked him to write an analysis of it. Dozens of other books followed, and in 1963 Crump’s first novel, Burn, Killer, Burn, was published by Johnson Publications. The book was a cooperative effort: Mattick bought Crump a portable typewriter, Father Jones smuggled the manuscript out of prison chapter by chapter, and Doris Saunders, then an editor with Johnson Publications, edited them. The book sold enough copies to pay off the mortgage on Crump’s mother’s house in Morgan Park.

While he was writing his novel and several volumes of poetry, Crump also mounted a one-man public relations campaign on his own behalf. He wrote to Lois Weisberg, who at first was not eager to get involved. “I wrote back that my newspaper was very small and had very little power,” she remembers. “I couldn’t imagine how we could help him. We were not into that kind of stuff; we were not a 'cause' newspaper.” However, Weisberg knew William Friedkin, now a celebrated Hollywood director (The French Connection, The Exorcist, and Cruising are among his films) but at that time a talented yet unknown filmmaker for Channel 7 TV in Chicago. Friedkin was working at Cook County Jail on a documentary and, at Weisberg’s insistence, met Crump. Friedkin immediately became fascinated by the man and the case, and his enthusiasm eventually convinced Weisburg to join the cause. Like his other supporters, Weisberg recalls being entranced the first time she met Crump: “He was very much alive, a very warm, friendly, exciting human being who was reaching out for help.” Weisberg’s newspaper was going out of business, but she postponed the farewell issue until June 1961: It was devoted entirely to the Paul Crump case. By this time, the U.S. Supreme Court had turned down Crump’s final appeal of his execution, and it was clear that a clemency petition to Governor Otto Kerner was the only option left. Weisberg persuaded Donald Page Moore to present Crump’s case.

Meanwhile, Friedkin had begun work on a documentary, The People vs. Paul Crump, for Channel 7. The film was an apologia for Crump: He was innocent. He had been brutalized by the Chicago Police. He should not be executed. Donald Page Moore, already preparing for the hearings, appeared in film, making a series of blunt accusations against the Police Department. “The history [of brutality by the department] is disgraceful; the tradition is bad; it’s worse than bad, it’s unconscionable…,” Moore said in the film. “I’m not just talking about Paul Crump; I am talking about the beaten and battered people whom I have seen with my own eyes.”

Later in the film, a sobbing Paul Crump described the beatings and his prayers for his life: “I started saying Hail Marys and Our Fathers because I wanted some help. When I started to pray, [one of the officers] came up to me, punched me in the stomach, told me to stop, and said, ‘What would the white Mother of God want to do with a black son of a bitch like you?’ ”

It was a gripping piece of film, but it presented two major problems. Throughout, Crump maintained that he was innocent and that at the time of the robbery and murder he was in bed with a girlfriend. That alibi, one of the main points of the film, later was proved to be untrue. Also, Moore’s strategy for the commutation hearings was already taking shape, and he decided that showing the film — with its claims of Crump’s innocence and police brutality — would alienate parole board and public alike and prove fatal to the case.

Moore’s plan was to admit publicly that Crump had committed a terrible crime but had been rehabilitated. People were still outraged about the murder and robbery, Moore says, and to debate Crump’s innocence further would be pointless — he had been convicted twice and had used up every appeal. “The crime was horrible; it couldn’t have been worse,” Moore says. “What kind of a man would do a thing like that? A beast. Now we just ask you in fairness to look at this man. He’s not a beast. He is a decent, religious, self-controlled, articulate, excellent human being.”

But by then Friedkin was eager to release his documentary, and Moore set out to prevent it. Friedkin was outraged, and in a violent — and final — meeting he accused Moore of cowardice and hypocrisy. That meeting was 21 years ago, and Friedkin and Moore have not spoken to each other since. Moore had used all his connections, and finally ABC network officials in New York had deep-sixed the film on the technicality that he had not obtained proper releases from the people who appeared in it. The People vs. Paul Crump has been shown only a few times in Chicago, although it has won critical acclaim elsewhere and is considered by some to have been Friedkin’s passport to fame and fortune.

To this day, even some of Crump’s most ardent supporters, such as Lois Weisberg, still ponder the issue of his guilt or innocence. Why did Crump lie about his involvement in the crime? Today Crump, while admitting that he killed, insists that it was an unplanned event that happened in the panic of a robbery. But exactly when he decided to change his story and why isn’t clear. Former warden Jack Johnson says that he never had any doubts that Crump had committed the crime, and that vehement denials are common among convicts.

“When they come in [to the prison], for the first few days they are remorseful, unless they are really hardened criminals,” Johnson explains. “They are willing to confess and tell you the truth of what they did. Then, a few weeks later, you get the ‘maybes’; two months after that, they start saying they’re innocent; and after six months they definitely have convinced themselves they’re innocent.” Crump hints that claiming innocence was part of his survival strategy: Other convicts waiting on Death Row had admitted their guilt and ended up getting executed anyway. But after the 1962 commutation, which was based on his rehabilitation, Crump figured that it was best to admit his involvement. “People would say, ‘He hasn’t admitted his guilt,’ and one of the first steps of rehabilitation is that you confess your guilt,” he says. Moreover, he realized that if he was ever going to be paroled, he would have to admit his guilt and also show contrition. “I came up before the parole board and the first thing they ask is, ‘Are you guilty? Are you sorry for the crime?’ I figured that I have to live, and I can’t live in the past, and the best thing for me to do is to try to put my best foot forward in my newly found life.”

While Moore was lining up witnesses for the commutation hearing, other Crump supporters were developing their own strategies. One was Miriam Rumwell, a young reporter with the Chicago bureau of Life and Time magazines. Rumwell, who had written several articles about Crump, decided that he deserved the advice of possibly the most famous criminal lawyer in the country, Louis Nizer.

Nizer lived up to his legendary reputation. With only two days to prepare, he plowed through thousands of pages of testimony from previous cases and appeals, and on the day the hearings began, a hot and muggy July 30, 1962, he was as familiar with the details as anyone could be. The room was packed with reporters and Crump’s supporters. As planned, Nizer and Moore pre-empted any description of the horror of the crime by readily admitting, as Moore puts it, that it was “a beast of a crime.” The issue became, was Crump a different man now? If so, the thinking ran, to execute him would be to kill a decent man. The hearings went smoothly enough except for the testimony of two witnesses: a psychiatrist, and Richard B. Austin, a former prosecutor in the Crump case who was then a Federal judge. Judge Austin described Crump as someone who appeared timid while in custody, but who nevertheless was capable of doing anything to avoid the consequences of his crime. With Moore’s prompting and advice, Nizer minimized the effect of Austin’s testimony by picking away at his recollection of the details of the case, which proved to be hazy since Austin hadn’t reread the trial transcripts before testifying. The psychiatrist, in effect, said that Crump could be classified as a psychopath, and that it was nearly impossible to tell whether his rehabilitation was real or a very elaborate charade. “A psychopath is noted for his cleverness. Even a psychiatrist can be fooled. We can’t tell,” the doctor testified. Nizer, as he relates the incident in his book The Jury Returns, turned the psychiatrist’s uncertainty to Crump’s favor by getting the doctor to admit that, psychopathic of not, Crump was a unique individual whose life should be saved.

It was not entirely a one-sided show, however. The argument of the young assistant state’s attorney, James R. Thompson, who was two-pronged: We couldn’t be certain that rehabilitation had actually taken place, and, even if it had, that was no reason to commute the death sentence. Moore, somewhat admiringly, recalls Thompson’s performance: “He was restrained. He hurt us just for that reason. And I think that he cared a lot more about the case than he ever showed. He was the very model of a great prosecutor. He didn’t do any of this lowdown rabble-rousing [such as dwelling on the gory details of the crime]. He was a gentleman. A merciless gentleman.”

Three days later, Governor Kerner commuted Paul Crump’s sentence. In his decision, Kerner wrote, “Before me is a voluminous record of testimony and affidavits from almost all of the people who have had any association with Paul Crump since his imprisonment nine years ago. This record is virtually unanimous that the embittered, distorted man who committed a vicious murder no longer exists. . . . Within this framework, Paul Crump must be accepted as rehabilitated.” The sentence was commuted to “199 years in prison without parole.”

Crump’s supporters rejoiced, but in retrospect Lois Weisberg recalls a sober observation made by warden Jack Johnson at the height of the push to save Crump from execution. “I am responsible for his rehabilitation, and I’m the one who will have to pull the lever on the electric chair,” Johnson said. “But I wonder if you peopIe really understand what you’re doing. If you save Paul Crump’s life, believe me, you will condemn him to a life worse than death in the Illinois prison system.”

The reality of Johnson’s warning did not become clear for about two years, when another round of lawsuits began over two words in Governor Kerner’s commutation statement: “Without parole.” Elmer Gertz, a close friend of the late Governor, says that Kerner meant “199 years in prison, unless paroled.” As evidence he cites personal conversations with Kerner and the fact that Crump had two parole hearings shortly after his commutation. According to Gertz, at one point in the controversy Kerner, by then on the Federal bench, considered sending a letter to the parole board but changed his mind, saying that it might be inappropriate for a sitting judge to involve himself in a parole dispute.

In 1970, Illinois attorney general William Scott issued an opinion stating the worst. “Without parole” meant exactly that, Scott said; Paul Crump was to be the only prisoner in the state who could never hope to be free. (Ironically, Scott himself would later benefit from an early paroIe following his Federal conviction for a felony offense.) Crump’s lawyers and the Illinois Division of the American Civil Liberties Union mounted a series of unsuccessful legal challenges which reached the U.S. Supreme Court. An amicus curiae brief filed by the ACLU vividly described Crump’s new quandary: “Only he, in the entire Illinois prison and sentencing systems, is totally barred from any chance of release from prison. . . . This is so shocking, so unbelievable, that one must immediately ask why the State insists upon it. . . .”

The Supreme Court refused to answer that question, and Crump’s supporters again petitioned the Governor to intervene. This time the matter was handled with much less fanfare by Donald Rothschild and Donald Moore, who was a personal friend of Governor Dan Walker. In 1976, shortly before he left office, Walker removed the “without parole” proviso from Kerner’s commutation order.

By now Paul Crump had spent 14 years in the state’s maximum-security prisons, and there were clear signs that his mental health had begun to deteriorate.

One factor was hopelessness. For 14 years, until Walker’s removal of the “no parole” proviso, Crump had been a man with no future except prison. As one prominent criminal psychiatrist observed in 1976, after evaluating Crump’s condition, “without hope, even an individual who is emotionally normal would in time begin to show signs of emotional disintegration.”

In addition, as Crump traveled through the state’s toughest prisons, he again became victimized by his own notoriety. He was first transferred to the state prison in Joliet, where he stayed about four months. Among the other inmates, Crump was a famous convict: He had beaten the electric chair; newspaper stories about his rehabilitation and his gaggle of celebrity supporters appeared all over the state; and, finally, he was a published writer. At Joliet, one of the officials figured that Pontiac maximum-security prison would be the ideal place to house Crump. The convicts there were mostly in their 20s and Crump, now in his 30s, could serve as an older role model. Prison officials at Pontiac, however, set out to prove that they were not impressed with either Crump’s reputation or his alleged rehabilitation.

“I had been publicized as a symbol of rehabilitation, and I guess symbols are made to be destroyed,” Crump says. The first day at Pontiac, the warden called Crump into his office and showed him a copy of his new novel, which had just arrived in the mail. “So you are Paul Crump?” the warden asked. “Here’s your book; why don’t you take a look at it?” Crump had just finished browsing through the dust jacket when the warden took the book back and said: “As long as you’re here, that’s about as close as you’re going to get to that book.” The typewriter Crump had brought from the County Jail was confiscated, as was the manuscript for a second novel that was three-fourths finished, along with several volumes of poetry. Guards periodically tore up his mail, flushing the pieces down the toilet with the typical comment: “Here’s your mail, nigger!” Crump became close to a younger convict, who treated him like an older brother. When guards noticed the developing relationship, the two were separated and the younger man committed suicide.

Crump had convened to Catholicism in his teens. At Pontiac, he attempted to befriend the Roman Catholic chaplain by having a copy of his novel mailed to him. It was a fatal error. A man in his 60s, the chaplain found the novel obscene, particularly a passage describing a relationship between a black man and a white woman. (In fact, if it were made into a movie, the plot might earn no more than a “PG” rating.) The priest decided to make his point one day when Crump and a number of other prisoners were in the chapel. He called Crump forward, and Crump innocently asked the priest whether he had read and enjoyed the novel. “No, I want you to know that I didn’t enjoy it,” the priest replied in a loud voice, in an act of public humiliation. “I want you to know that it is a filthy and nasty book and that I threw it in the trash can.” Crump walked out of the chapel and he says that he hasn’t been to church since.

Cook County Jail warden Johnson, who witnessed Crump’s rehabilitation, visited him several times after Crump left and says that, in effect, he also witnessed the destruction of a man. “The biggest mistake they ever made was to send Paul to Pontiac,” Johnson says. “The warden had an eye-for-an-eye mentality, and they treated Paul very badly. I saw him go down, down, down, to the point where they turned him into a vegetable.”

Crump was later transferred to Stateville Prison, the meanest and most violence-ridden institution the Illinois correctional system has to offer. There his mental health continued to deteriorate. He developed a severe psychosis — he was sent to Menard Psychiatric Center for treatment. A pattern was now established, and it would be repeated at least seven or eight times: Crump would recuperate in the more humane surroundings of Menard, but relapse shortly after being returned to Stateville. Finally, his lawyers asked that he be permanently left at Menard. His is there today.

Ruthanne DeWolfe, a lawyer and psychologist, has been monitoring Crump’s mental health for eight years. The symptoms of his mental breakdown, she says, include such bizarre behavior as howling like a dog all night, smearing feces over the cell walls, and refusing to tie his shoelaces for reasons that make no sense to anyone else. The loss of his manuscript and poems at Pontiac seems to have been a bitter blow. DeWolfe adds that his hopelessness during the 14 years he lived without the possibility of parole also contributed to his decline.

Despite the renewed opportunity for parole, at 53 Crump’s chances of release have not improved. Since 1976, he has been turned down six times. The reasons are hard to piece together because the current members of the Illinois Prisoner Review Board refuse to say much in view of Crump’s latest lawsuit.

The first three times he was refused parole, the board tersely explained that his release “would deprecate the seriousness of the offense.” In fact, the average length of imprisonment for a convicted murderer in Cook County is 8.4 years, and even in the most extreme cases murderers are paroled after no more than 15 years.

What has made Crump so special, such a unique danger to society? His lawyers reason that perhaps it was the publicity, and so between 1977 and 1981 they advised Crump not to grant any interviews in order to keep the lowest possible profile on the case. Gertz made that decision when, just before a parole hearing, one of the board members was heard to mutter: “Here comes Paul Crump and his Jew lawyers!” Gertz and Rothschild also successfully challenged the “deprecation” rationale, arguing that it was first adopted after Crump had become eligible for parole hearings and therefore could not be used ex post facto.

Maybe it is because the parole board really fears that Crump is psychotic and therefore dangerous. The current chairman of the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, Paul Klincar, refused to cite specifics and answered my questions only with questions of his own: “Do you know that he is in for murder? Do you know that he was sentenced to the electric chair? How do you know that he is rehabilitated? Everyone’s got a different definition of rehabilitation.” In the end, Klincar’s argument seemed to focus on Crump’s mental health. “The Department of Corrections put him at Menard, and he is there for a reason,” he said.

However, every psychiatrist who has examined Crump, including those with the Department of Corrections, has found him psychotic but nonviolent. To allay the fears of parole board members about Crump’s behavior after his release, a group of psychiatrists and counselors, including Ted Ramsey, who at the time was the chief of counseling services with the Illinois Department of Corrections, formulated a post-release treatment plan specifically for Crump. It provides for whatever inpatient and outpatient treatment he might require at Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center’s psychiatric unit, for however long it may take. Filmmaker Friedkin, who still comes to Chicago to testify at Crump’s parole hearings, has offered to pay the estimated $14,000 that such treatment would cost. At a recent hearing, Ethel Gingold, a board member who dissented from the majority’s decision, commended Crump’s elaborate postrelease plans as the finest that had ever been presented.

Psychologist Ruthanne DeWolfe adds that Crump has a remarkable circle of supporters waiting for his release. That includes his 90-year-old mother, who lives at the same house in Morgan Park where Crump lived at the time of his arrest 30 years ago. Crump’s wife, whom he married in 1976 in one of the first wedding ceremonies allowed in an Illinois prison, visits him each anniversary and vows that, upon his release, she will immediately move back to Chicago from New York. They met before he was arrested and have two children and five grandchildren. In a recent letter to the parole board, she wrote: “I don’t know what the future holds for Paul and myself, but no matter what it holds, I will go on the rest of my life devoting myself to him and doing all I can to make life a little easier for him.”

DeWolfe, who performs periodic psychological evaluations of Crump and visits him regularly, says that while his mental problems are severe, they are episodic and easily treatable with drugs, and that, at any rate, mental illness is no reason for keeping someone in prison. “If the members of the [parole] board can’t tell the difference between the violent and the mentally ill, they should be replaced,” she says. “If their knowledge of human behavior is so shallow, so medieval, they have no business sitting on that board.” She adds that, statistically, murders are committed by younger men, and that the chance of a 53-year-old’s committing a similar offense after 30 years in prison is virtually nonexistent.

In the past two years, members of the parole board have hinted that Crump must pass a crucial test to “prove” that he is ready to rejoin society: He must spend an indeterminate period of time back at Stateville Prison and survive without any further mental breakdowns. However, Ramsey says that that is a ludicrous stipulation. “Prisons are abnormal settings, and your ability to get along in an abnormal setting is no proof of your ability to get along in the street,” he says.

In the end, Ramsey agrees that Crump’s notoriety has kept him in prison. “If he were to get a parole, it would be covered in the papers and TV, and if he were to do something off the wall after his release, it would be a major embarrassment to the parole board,” he says. “Paul would have been released by now if he had not been a celebrity of sorts.”

Elmer Gertz, who says that Crump’s freedom would be the culmination of his legal career, is confident that the latest lawsuit will have that result. The suit asks for his release and two million dollars in damages; Gertz and Rothschild have been taking depositions from prison officials and members of the parole board.

For his part, Paul Crump says he doesn’t know whether he should hold any hope for his future. “Right now, I live on the hopes of my family, my friends, my loved ones,” he says. “I don’t know about myself, but if there is anything I am determined to do, it is to realize the faith they have put in me over so many years.”