A couple of blocks west of the bustle of Broadway, where that street passes through Little Saigon, a low-slung yet imposing two-story red brick structure hugs the south side of Argyle, between Magnolia and Glenwood. Surrounded by quiet apartments and standalone homes, the factory-like building with large multipaned windows, their trim painted green, bears little trace of its epoch-making past, offering few justifications for its landmark status save a peak-roofed entryway tiled in creamy white with verdigris lanterns on either side. This is the former Essanay Studios, at 1345 West Argyle Street in Uptown. Today the building contains an auditorium named after Charlie Chaplin, but over a hundred years ago — for an ephemeral span — it contained the man himself.

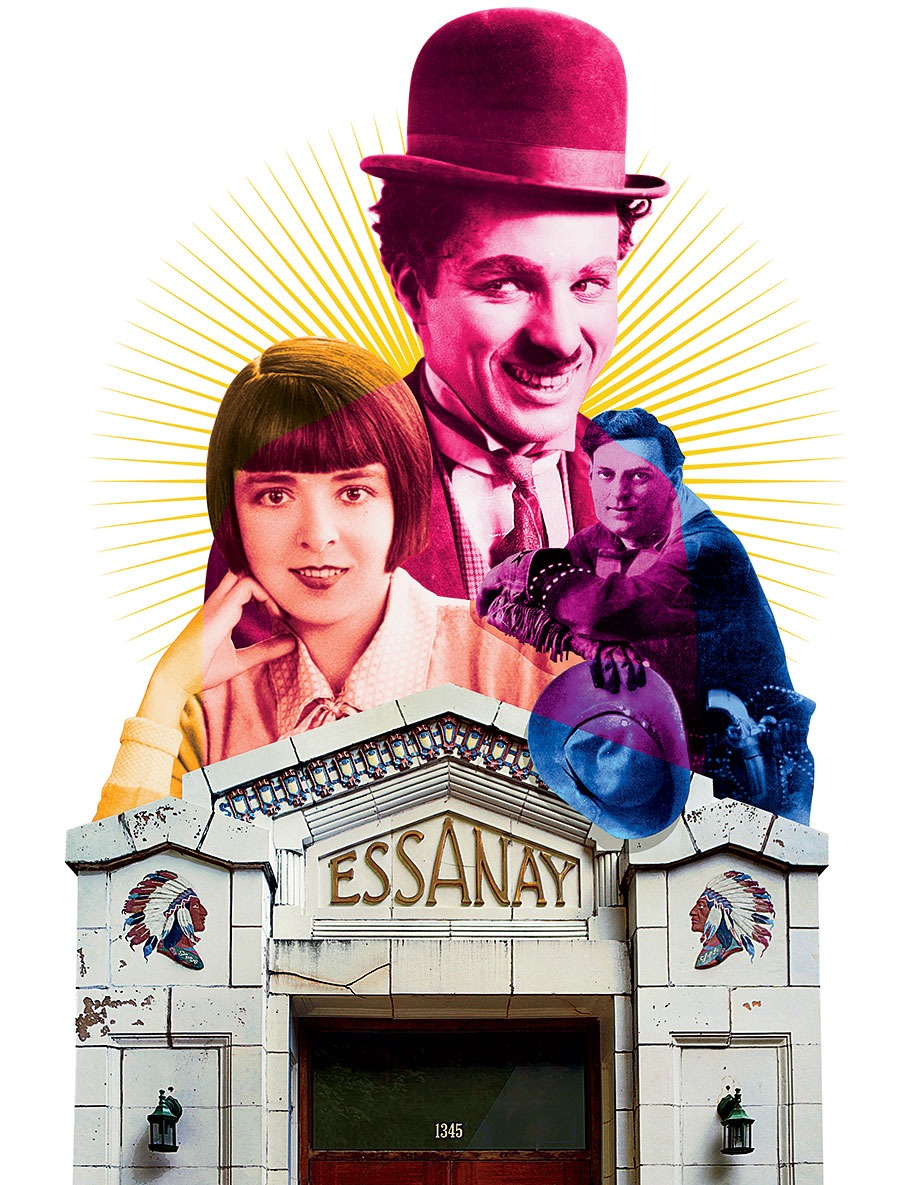

The plaque on its façade, hung in 1996 at the city’s granting of the landmark status, explains: “The terra-cotta Indian heads flanking the entrance were Essanay’s trademarks.” These bas-relief heads in feathered headdresses, extravagantly painted, gaze eye to eye across the stylized type reading “Essanay.”

From 1908 to 1918, the building, now owned by St. Augustine College, was the locus of the filmmaking enterprise of George K. Spoor, an early movie pioneer originally from Highland Park, and Gilbert M. Anderson, an actor whose vaudeville days in New York City eventually led him to the fledgling film industry. Today we refer to the genre as “silent movies,” but at the time, they were just movies. Few sat around thinking about what this new form of entertainment lacked; they were too busy being wowed by what moving pictures had: handsome actors and beautiful actresses, rollicking musical accompaniments, heart-rending tragedy, and gags upon gags.

Anderson himself was arguably the earliest western movie star, appearing in 1903’s The Great Train Robbery, and going on to fame as Broncho Billy, a character he created and portrayed in 376 pictures. In fact, not far from the remnants of Essanay lies the Chicago Park District’s Broncho Billy Park, at 4437 North Magnolia Avenue, a half acre with a splash pad and squishy-surfaced playground, all named in honor of this cinematic cowboy. (Speaking of gags, Anderson directed a film for Essanay in 1909 called Mr. Flip, which features what is said to be the first known instance of a pie in the face.)

Founded in 1907 as the Peerless Film Manufacturing Company, the studio was originally headquartered at 501 North Wells Street (1360 North Wells today, accounting for street renumbering). Later that year, Spoor and Anderson changed the name (S and A — get it?) . With profits from such successes as An Awful Skate; or, The Hobo on Rollers — starring Ben Turpin, the studio janitor at the time — they moved in 1908 to the bigger location whose fading traces I love so much.

Chaplin moved to Chicago around Christmas 1914, lured by a contract offering a rate of $1,250 per week, making him the highest-paid film actor in the world.

I can’t recall the exact day I laid eyes on the place, but I remember that it was back in the early 2000s, when I was working in Senator Dick Durbin’s Chicago office. We were up there from the Loop, visiting the college for some community outreach or press event. A colleague mentioned in passing that the site had been the home of the movie industry before business trends and Chicago’s dreadful winter weather drove most of the starry-eyed hopefuls west.

Ever since, I’ve been a fan of wandering by, alone or showing someone else. When I’m with another person, I like to tell them stuff like this: Though short-lived, in its 11-year existence, Essanay made 2,000 films that became foundational for both the industry and the art form, the most enduring of which is The Tramp, featuring Charlie Chaplin. The vagrant character of the title, a bumbler about town with goofy shoes, too-big trousers, gentlemanly airs, and a generous heart, is one near and dear to my flâneuse’s heart.

That film was shot at Essanay’s outpost in Niles, California, but Chaplin moved to Chicago around Christmas 1914, lured by a contract offering a rate of $1,250 per week, making him the highest-paid film actor in the world. Alas, Chaplin never developed an attachment to the Windy City, shooting only one of his 15 total Essanay comedies, His New Job, at the Argyle location before departing permanently for California in January 1915.

While he was here, he supposedly lived in the penthouse of the Brewster, at 2800 North Pine Grove Avenue, an 1896 building a little over three miles from Essanay that still stands. In an essay for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, film scholar Jeffrey Vance wrote that Chaplin’s year at Essanay marked the company’s “zenith” and that the studio “foundered after Chaplin left to join the Mutual Film Corporation in 1916 and finally ceased operations in 1918.” Vance argues that Essanay “would likely have been forgotten were it not for Chaplin’s association with it.”

That might be true, but a number of other significant actors came and went through that terra cotta entryway, including a teenage Colleen Moore, back when she was still Kathleen Morrison. She’d hang around and watch the movies being made when she was up from Tampa, visiting her aunt and uncle who lived nearby on Sheridan.

Though nowadays she is, tragically, lesser known than Chaplin as a brilliant comedian, this great and unjustly forgotten female star ended up getting her start at Essanay, recording the screen test that (in combination with the string-pulling of her well-connected newspaper editor uncle Walter Howey) resulted in her big break: a brief contract with director D.W. Griffith’s studio in California that she parlayed into superstardom in the 1920s as America’s preeminent flapper.

Eventual diva extraordinaire and Chicago native Gloria Swanson also had her humble beginnings at Essanay, starring in comedies before she became better known for her glamour. And renowned Japanese American photojournalist Jun Fujita worked as an actor at Essanay in the 1910s, even starring in Otherwise Bill Harrison in 1915. (That same year, he photographed the horrific sinking of the Eastland in the Chicago River.) Fujita stopped acting once the industry moved west and instead continued to work for the Chicago Evening Post and the Chicago Daily News. In 1929, he was the only photographer to document the aftermath of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, and he also published poems in Poetry magazine.

I like telling people all this stuff about Essanay and the luminaries who passed through because in our contemporary age, when filmmaking is becoming more and more geographically decentralized, it’s worth remembering that before the Hollywood studio era, great screen acting could take place anywhere.

In his introduction to the wonderful historical novel Black Robe by Irish Canadian author Brian Moore (no relation, as far as I know, to Colleen), Colm Tóibín writes of Moore having his imagination sparked by a collection of letters sent by French Jesuits in the New World: “This is how novels begin — stray reading or random experience hitting a vulnerable spot in the nervous system, or stirring the set of personal histories and obsessions which we all live with.” The random experience that hit my vulnerable spot in the case of my own latest novel, From Dust to Stardust, based on Colleen Moore, arose not from reading but from walking around Chicago, which often seems to me similar to reading: A person can peruse the built environment with their feet as though it were a text, absorbing remnants of the past that have mostly vanished but emerge unexpectedly into the present.

Tramping around like Chaplin’s Little Tramp, you never know what you’ll see — or where whatever you see might send you. Just as Chaplin sent the Little Tramp walking silently down a long highway into the horizon at the end of his last film to feature the character, 1936’s Modern Times, the industry headed toward the western sunset as well, and Essanay closed in 1918.

But through a series of Hollywood-style twists and turns — her life, after all, was the inspiration for the 1932 film What Price Hollywood?, which in turn influenced the original A Star Is Born — Colleen Moore herself ended up back in Chicago sometime in the mid-1930s. The stunning miniature Fairy Castle at the Museum of Science and Industry, sumptuous as any film set, is her creation. But that’s a story for another city walk.