On March 22, 2002, sheriff's deputy Adam Streicher was the only cop on duty in Toulon, Illinois, a town of 1,400 that briefly pokes up between cornfields, the municipal equivalent of a prairie dog. Toulon is located 160 miles southwest of Chicago and it feels even farther. Most folks farm the land or work for the town. The lone grocery store has wood floors and hand-drawn signs. A flashing yellow light slows traffic on Main Street.

Deputy Streicher, 23, had dreamed of becoming a cop since childhood, when he admired Ponch, the hero of the TV series CHiPs. He had grown up in nearby Annawan, so he knew the rhythms and mores of rural Illinois. As a Stark County deputy, he would be responsible for covering the county's three main towns—Bradford, Wyoming, and Toulon—in an area considerably larger than Chicago. Often, he was the only law enforcement officer on duty in the entire county. Streicher had been on the force just three months, but he handled his rounds with confidence.

On a Friday night like this one, an ambitious deputy might nab some beer-chugging teenagers or issue a "Settle down, folks" to a bickering couple. But Streicher didn't intend to sit. He nosed around the Stark County deputy's office—there was usually something if you looked—and found a five-month-old warrant for the arrest of a local man. It seemed routine enough—the man had failed to pay some court fees and had missed his court date. Dressed in starched brown pants and brown shirt, with a stark county silver badge covering his left breast, Streicher found the squad car keys and began the four-block ride to the man's house.

In Toulon, people mind their business. But anyone who had known Streicher's plan would have spoken up; they would have warned him, Don't do this. But Streicher did not know what Toulon knew.

The deputy turned right on Main Street, left on Miller, and right on Thomas. It took him a minute to arrive at the house of the man named in the warrant. Carrying the document, Streicher walked to the front door and knocked.

Nobody in Toulon pretends that the place is Mayberry. It once was, maybe, in the 1950s, when the town supported an active Main Street, four car dealers, four new farm implement dealers, and three doctors; when the city constable was a one-armed geezer who patrolled on foot and shook business doors to check the locks; when America valued its farmers. That's history now. In Toulon, as in many small towns, young people worry about opportunity. The talented nurture an appetite for the larger world. Empty storefronts embarrass Main Street.

Still, Toulon has its advantages, and they are the kind that don't defer to eras. Everyone knows each other here, not just by name but by hopes, dreams, victories, and disappointments. A newcomer who buys the Williams house will live in Toulon a decade before residents stop referring to it as the Williams place. Gossip—the small town's nectar—is reliably ladled in the town's two coffee shops, ladies at one table, men at another.

But Toulon's biggest advantage is in its biology. The town exists as a living, unified being; no part moves without implication for the other parts, no person lives without affecting other lives. When someone in Toulon gets sick, much of the town rushes to her bedside or comforts her children or takes over her household chores. When someone in Toulon dies, the town converges for fundraisers, selling candles or car washes or whatever it takes to make the system whole again. In this way, by merging into a single, 1,400-person organism, Toulon survives.

Residents aren't naïve enough to believe that bad things can't happen in Toulon. But what they never imagined was that certain kinds of bad things—maybe the worst things—could happen in a place like Toulon because it is small, because everyone knows each other, because the people are so close.

Deputy Streicher waited for an answer at the man's door. The house and property stood out from its tidy neighbors; logs, tires, and appliances lay around the modest carport, forming a meniscus of junk that crawled along the edges of the house. A small yellow tractor sat parked near the front door. A wooden swing on a faded red metal stand stood sentry on the tiny patch of yard.

(The following events of the evening of March 22, 2002, as described here, are drawn from law enforcement allegations and court records including a 30-count indictment, as well as Chicago magazine interviews with witnesses and other sources.)

A 60-year-old man with Einstein salt-and-pepper hair, a disorganized gray beard, and frozen eyes answered the door. He stood perhaps five feet nine. His name was Curtis Thompson, and he was a former coal miner who had lived in the area all his life. Apparently, Deputy Streicher announced the purpose of his visit—to serve an arrest warrant. A brief conversation ensued. Shortly thereafter, law enforcement officials and the indictment allege, Thompson located his sawed-off shotgun and pointed it at the deputy. Before Streicher had much of a chance to react, Thompson pulled the trigger, hitting the deputy in the left shoulder, upper chest, and neck. Streicher fell to Thompson's porch, his face dusted with gunpowder, shotgun wadding stuck to his shirt collar, his upper left side blown away. He likely died before he hit the cement.

Streicher lay on the porch in a pool of blood. Then, the indictment alleges, Curt Thompson took the officer's nine-millimeter pistol and, along with the shotgun, jumped into the deputy's squad car, flipped on the flashing lights, and proceeded down Thomas Street, a glaring, enraged monument to a small town's recent history.

For 30 years, some of the people of Toulon had worried that it could come to this. Curt Thompson was a terrifying bully. He selected his enemies for committing offenses few could fathom, then punished them through methodical stalking—sometimes for years—that derailed their lives and infused them with fear. "He was the meanest person I ever met," says a man who knew Thompson. "He wanted people to be afraid of him, and spent years making threats."

People filed numerous complaints against Thompson. Mayors, city councils, prosecutors, and law enforcement seemed powerless to stop him. (State's Attorney James Owens, Stark County sheriff Lonny Dennison, and Toulon's lone police officer, Bob Taylor, would not comment for this story.)

A handful of Toulon residents claim that Thompson was misunderstood. They attest to his intelligence, work ethic, kind wife, and instinct to help those in need. Some even mention his sense of humor. "There was quite a bit good about him," says Mary Jane Swank, whose husband is Thompson's cousin. "There was nothing Curt wouldn't do for you." Few, however, express complete surprise at how things turned out for Thompson and Toulon.

The shock came when Thompson began to terrorize people. Then, Toulon's strength—its smallness—became its biggest liability. Residents who otherwise massed to help neighbors now advised one another to "just ignore" Thompson. Police counseled citizens to "just stay away from him." In the town's two coffee shops, headquarters for Toulon's get-involved impulse, the mantra on Thompson became "You know how Curt is. Just leave him be."

Several decades ago, the town of Skidmore, Missouri, suffered under the rage of its own bully. Ken McElroy, a hulking, 47-year-old farmer with long black sideburns, manufactured feuds and then stalked his foes. For years, McElroy defied authorities. One day in 1981, a posse of 30 or 40 followed the bully to his truck and, in broad daylight, shot him dead. When authorities asked for witnesses, no one came forward. The case remains open. By midnight on March 22, 2002, some in Toulon would be wondering if the same fate shouldn't have befallen Curt Thompson.

The details of Thompson's life are sketchy. Acquaintances say he grew up on a farm near Toulon, the youngest of several children. His father died when Curt was six years old, leaving the family to struggle for the basics.

"Curt had to go work on farms when he was in grade school," says Barry Taylor (no relation to Bob Taylor), who knew Thompson when they were children. "It's a rotten childhood when you have to work in grade school."

"His mother was good in ways," recalls Mary Jane Swank. "She could be stubborn; things had to be her way. She didn't want anyone to touch any of her stuff, and she raised her kids like that. If she got mad at someone, she'd hold that against them forever. But she was smart, and she was a beautiful writer."

Taylor recalls Thompson as bright, serious, and an excellent high school football player for Toulon High School (now Stark County High). He tells that Thompson had to quit school at 16 to work full-time. "He had no choice. He had to eat."

Thompson married a girl from his high school class, a woman Taylor describes as "fun and nice and pleasant," and to whom he is still married. He went to work on various farms, then took a job in an Illinois coal mine. Without exception, those who knew him describe him as a capable and hard worker able to do almost any odd job or farm task. Somewhere along the line, however, Thompson began to get very angry.

At the Stark County courthouse in Toulon, where Abraham Lincoln spoke in 1858, records of legal proceedings are still entered by hand in hefty leather diaries. Under the letter "T," going back more than 30 years, are myriad cases against Curt Thompson.

Some appear harmless enough: a dispute with an employer; traffic citations; failure to keep a dog's vaccination records current; violation of a litter ordinance. But others seem bonded by a common theme—vendetta.

For decades, Thompson maintained grudges against various Toulon residents. Anyone who had taken him to court, or who he perceived had complained about him or violated his sense of territory, made his enemies list, and it was a list often written in indelible ink. As town talk had it, those who angered Thompson might expect to live in constant fear.

"Fear" does not mean in Toulon what it means in Chicago. In Toulon, where most residents live a few blocks from each other and pass on the street several times a day, having an enemy virtually assures a meeting with him in public. When that enemy is Curt Thompson, an intelligent man with time on his hands who dedicated thought and energy to creating fear, it could ruin your life.

Thompson's modus operandi, at least in recent years, was predictable and intimidating. According to many, he would drive his pickup truck past the home of his foe, slow to a crawl, and glare. He might follow his enemy down the rural roads that led out of Toulon, or block him with his truck at intersections. Always, he would glare.

"He was a bully," says Jim Pearson, who worked as a Stark County deputy from 1982 to 1987, and who now works as a Peoria County sheriff's lieutenant. "The glaring, the following, the threatening—he even did it to elderly people."

"Everyone knew about his temper," says one of Thompson's neighbors, who asked that his name be withheld. "He held a grudge. If someone bothered him, he'd bother them back, and he'd stay at it. I told Curt, 'I don't hold grudges.' He said, 'Well, I do.'"

Early on, Toulon evolved a defense against Thompson that seemed to run counter to its instinct to unify against threats. Whereas the town would mobilize to save a school or care for a sick child, it largely decided to ignore Thompson, to maintain a safe distance, to cross to the other side of the street.

"People talked about Thompson being crazy," says Art Mott, who has lived in Toulon for ten years. "The thinking was to stay away from him."

"It was a small-town mentality," says another Toulon resident. "People thought: Nothing major is going to happen; he's just crazy; ignore him; he's been harassing people for years, so just ignore him."

No one remembers any formative incident in Thompson's life that might explain the roots of his temper. Rather, it appears that his encyclopedia of grudges grew out of his particular notions about territory. "He wouldn't have a problem with a stranger on the street," says one person who knew Thompson. "But if your trash blew onto his lawn, he'd have a big problem with that. Personal space was a big issue with him."

Unlike most bullies, Thompson targeted more than the weak. Sheriffs, politicians, even black belts in karate qualified for vendetta if they managed to wrong Thompson.

In 1984, Toulon's mayor, Rick Collins, followed up on a citizen's complaint against one of Thompson's dogs. "That started Curt's grudge against me," says Collins, now a commercial pilot for a major airline. The next year, he and Thompson attended a retirement party for a bus driver at a restaurant just outside Toulon.

"I nodded across the table, a friendly hello," Collins says. "He glared. Later, as I was leaving, Curt came up behind me, threatening me with all kinds of profanities. I ignored it. He struck me a couple blows to the head, then pushed me down a small flight of stairs. I hit the bottom on my hands and knees, but just got up and kept going. Had I gone after him, the only way the confrontation would have ended would have been death or jail." Neither the Toulon city policeman nor the Stark County sheriff, Collins says, was interested in pursuing the matter, claiming it to be outside their jurisdictions.

In 1980, Thompson had a run-in with Kenneth Richardson, then the Toulon city policeman. Thompson and Richardson owned adjoining properties. While working outside, Thompson and Richardson began to argue about the property line. A struggle ensued, during which Richardson managed to get atop Thompson and hold him down.

"I had gone to take a bottle of pop to my husband," recalls Sandra Richardson, Kenneth's wife. "When Curt saw me, he yelled to his son, 'She's going to hit me with that bottle! Get her or I'll get you!'" She alleged in a lawsuit that Thompson's son, a football player, ran and tackled her and broke her wrist in six places.

The Richardsons filed two lawsuits. The first, by Kenneth, claimed that Thompson had punched him, and had been "verbally abusive, hostile and obscene" for weeks before the incident. The second was filed by Sandra against Thompson's son, Curtis Jr.

"After that," Sandra says, "Curt would sit at the stop sign at the end of our driveway and glare."

One law enforcement official who seemed willing to confront Thompson was Kenneth "Buck" Dison, the Stark County sheriff from 1970 to 1982. For nearly 30 years—well into Dison's old age and retirement—Thompson maintained a feud with the sheriff.

No one knows for certain the origins of the dispute. Court records show that Dison arrested Thompson in 1971 after Thompson allegedly threatened a man at a Toulon feed store. It didn't take long, according to many, for the feud to blaze.

"Curt would come after Dad every time he saw him," says Kathy Ptasnik, Dison's daughter. "He backed up his truck and glared into the house when my parents were socializing. He'd follow Dad and flip him the finger. Dad was afraid of Curt having revenge. He told us never to walk past his house." Even among her siblings, Ptasnik says, the instinct was to turn away from Thompson. "My brother and I begged Dad to ignore him," she says.

"Dison didn't take any shit," says Collins, the former mayor. "He wasn't afraid to stand up to Curt." Others say Dison gave as good as he got. "After Buck had retired, I saw him flip Curt the bird when Curt was just minding his own business," says a friend of Thompson's who asked to remain anonymous.

In 1987, Thompson pulled his pickup in front of Dison's car on a rural road, blocking the former sheriff. Thompson got out of his truck and approached Dison's car. The two men argued and, Dison claimed, Thompson threatened him (Dison was 68 years old at the time; Thompson was 46). Thompson was charged with reckless driving and disorderly conduct.

At trial in the plain white courthouse on Main Street, Thompson testified that Dison had been harassing his family. He stopped the former sheriff, he said, to warn him against bothering his family. "I told him, 'You fucking old man, you pull it again, and I'm coming after you.'" When asked if he always stopped those he was angry with on a public road, Thompson testified, "It depends on where they are."

The jury convicted Thompson on both charges. He was fined $150 and sentenced to 21 days in jail. The disorderly conduct verdict, however, was reversed by the Third District appellate court, which reasoned that the trial judge had improperly excluded testimony about the long-running feud between Dison and Thompson and his family.

Seven years later, in 1994, Dison claimed that Thompson approached his car in the parking lot of the local grocery and threatened him. This time, Thompson was charged with aggravated assault and disorderly conduct. At trial, he denied leaving his truck, but acknowledged the gist of the remarks. "I told him to go on in the store or I'd bury his ass," Thompson told the court. In arguments before the judge, prosecutor James Owens called Thompson "a street thug" and "a schoolyard bully who never left the schoolyard." Thompson was convicted of disorderly conduct, but not the more serious charge of aggravated assault. He was sentenced to a year of probation, $111 in court costs, and 100 hours of community service.

"Up until the end of Dad's life, Curt harassed him," Ptasnik says. "Dad was an old man in very poor health. He used a walker! And Curt would still pull up beside him and give him that glare. [Dad] was so upset that nothing could be done about Curt, but not just for himself. He was convinced Curt could kill someone."

The Richardson "pop bottle" cases lay dormant for four years before being dismissed for lack of pursuit by the plaintiffs. "I think they dropped it because the judge was retiring," Sandra says. "No one was interested in pursuing it."

The idea of "not pursuing it" became central to Toulon's approach to dealing with Thompson. A few, like the Richardsons, filed charges and took Thompson to court. Many more opted to ignore him.

"People would come in and complain," says Pearson, the former deputy. "They would tell me about the intimidation. But almost no one would file charges. They just put up with him for the most part. The thinking was to ignore him, and hopefully things would get better."

"I think people rationalized that the problem wasn't severe enough to justify the effort required to resolve it," says Jim Nowlan, editor of the Stark County News, a weekly newspaper. "I might have been guilty of it myself."

Nowlan and others in Toulon tell of hearing several years ago that the Toulon City Council did not intend to enforce a litter ordinance against Thompson. "That infuriated me," Nowlan says. "I thought the whole town should go over there at once and confront Thompson. I thought we should be united. But my passion cooled and I ultimately forgot about it, and that was probably pretty typical."

Some suggest, too, that law enforcement was afraid of Thompson.

"The various police from the town and county over the years, not all of them, but some, have been fearful of Thompson," Nowlan says. "Not in terms of the old-fashioned fistfight, but for fear of an extremely violent reaction."

Pearson has another take. "We were in a tough situation," he says of law enforcement. "It's not against the law to drive your car down a public road or an alley and glare at someone. When [Thompson] did something more serious and someone was willing to file charges, action was taken by the police. But most people chose just to ignore him."

And the few in Toulon who were willing to file charges were the people Thompson was on his way to see after he allegedly killed Deputy Streicher.

Jim and Janet Giesenhagen were perfectly Toulon. His mother, Ardelle, lived across the alley on a homestead bought by her great-great-grandfather in 1829. Jim co-owned a local television/heating/ air-conditioning business, earned a black belt in karate, attended church every Sunday, led a Boy Scout troop. Janet worked long hours at a Peoria grocery store, about an hour away, then went home to play with their daughter, Ashley, and surf the Internet. Ashley played soccer and piano, and remained a Daddy's girl. Most Friday nights the family went out for supper, often for pizza at Happy Joe's in Kewanee. Their future plans were simple: Save money for retirement, make a trip to Disney World.

In 1986, the Giesenhagens told police that Thompson's Labrador retriever had bitten six-year-old Shawn Henderson, Janet's son from a previous marriage, who lived with them. Stark County authorities filed charges, and the case went to trial. The jury found in favor of Thompson. The Giesenhagens were now on Thompson's list.

Ardelle Giesenhagen, Jim's mother, and others say Thompson began to stalk the Giesenhagen family, and kept it up for years. "Day after day, around eight in the morning, Curt would drive down the alley behind Jim's house, just circling very slow, three or four times, almost not moving, and glaring," recalls Joe Tracy, Jim's best friend. "He knew that was about the time Ashley went to school. And it didn't quit. Jim made complaints. Nothing was ever done."

Jim began driving Ashley the few blocks to school. In his car, day or night, he zigzagged rather than take the shortest route, always careful to avoid passing near Thompson's house. Though Jim held a black belt in karate, he rarely, if ever, confronted Thompson; he knew that the man owned guns, and believed that a challenge might short-circuit Thompson's temper.

Ardelle Giesenhagen, then in her 60s, was not so patient. After Thompson extended his vendetta to her and her husband, and began to circle her house and glare at her, she told him, "Curt, you're not God! I'm not scared of you. You could shoot me today and it wouldn't worry me because I know where I'm going. But I don't know if you're going anyplace but down below." Thompson just glared at her. Another time, when he parked in the alley and glowered while Ardelle gardened, she shook her finger at him and said, "Curt, what do you think you're doin'? Move it!" Thompson only snickered and drove off.

Perhaps the moment that most frightened Ardelle occurred just after her husband died, in 1999. She, Jim, Janet, and Ashley were in her backyard playing with Ardelle's cats. "Curt drove his truck down the alley and told Jim and Janet he was going to kill them," Ardelle recalls. "Someone called the police. Bob Taylor came. Curt said he'd get him, too. Taylor did nothing. He didn't arrest him. Nothing."

About five years ago, shortly after Joe Tracy went to work for Jim Giesenhagen, he, too, began to have problems with Thompson. "I had no connection to Curt, no dealings with him," Tracy says. "My only offense was that I was friends with Jim."

Sometimes, Thompson would block Tracy on Main Street with his truck or follow him out of town or try to run him off the road as he walked to the grocery store. Every day, Tracy says, Thompson circled his house, glaring. When he told Thompson, "Curt, why don't you just leave us alone? We're not bothering you," Thompson replied, "Yes, you are bothering me. You're harassing me all the time," and Tracy could only shake his head.

In 1999, Tracy filed a criminal complaint claiming that Thompson had followed him for two miles into the country, then jumped out of his truck at an intersection and waved a hammer threateningly. Jim and Janet Giesenhagen gave statements about Thompson's behavior in connection with that case. Thompson was convicted of simple assault, and in August 2000, he was ordered to pay $116 in court costs, $25 per month in probation fees for 24 months, and a $100 public defender's fee. He was also ordered to stay away from Joe Tracy and his family, and from Jim Giesenhagen and his family—an order Tracy says Thompson violated repeatedly.

"Jim didn't know what to do," Tracy says. "He went to the law, he made lots of calls, and they didn't do anything."

Finally, Jim set up a video camera on the back of his garage and pointed it toward the alley. Thompson drove by and glared. Often. Jim and Tracy believed that this was clear evidence of violation of the court order prohibiting contact with the Giesenhagens. Jim delivered the tapes to the state's attorney. Tracy says they never heard back.

More than a year after the conviction in the hammer-waving case, Thompson had paid just $18 of the required fees and costs. Judge Scott Shore issued a summons for him to appear before the court for nonpayment. Thompson did not appear. On October 15, 2001, Shore issued a warrant for Thompson's arrest. It was this warrant that Deputy Streicher had tried to serve the night he was shot, more than five months after it had been issued.

On that Friday night last March, while Deputy Streicher lay on Curt Thompson's porch, Thompson streaked in the squad car toward the Giesenhagen house. Inside, the family was enjoying a quiet evening together. Janet was on the couch. Jim and Ashley had gone to the basement, probably to fetch a vaporizer to soothe Janet's asthma.

Court documents allege that, armed with Streicher's service revolver and his own sawed-off shotgun, Thompson pulled into the driveway of the house, smashing the rear end of a parked Mercury SUV and driving it through wooden fence posts and into a pole flying the American flag. Thompson jumped out of the vehicle with the shotgun. He climbed the four wooden steps that led to the side door of the house, leaving the squad car lights flashing in the driveway. Then, the indictment alleges, Thompson broke down the door to the house and burst in, carrying his sawed-off shotgun. At close range, he fired at Janet, hitting her in the arms and the chest, leaving her left forearm dangling by a thread of skin as she collapsed to the floor. Then, authorities say, he likely moved to the basement, where he fired the shotgun and struck Jim Giesenhagen in the face, the buckshot obliterating his tongue and the floor of his mouth. Jim fell dead. Thompson did not harm Ashley, who probably witnessed her father's killing. Finished, Thompson left the house.

Ashley called her grandmother, Ardelle. Toulon does not have 911 service; the town voted it down twice, thinking it too expensive, at $2.85 a month, to adopt. Ashley told Ardelle, "Grandma, come quick! Curt Thompson just killed my daddy and hurt my mommy." Ardelle, who did not know whether Thompson was still inside the Giesenhagen home, threw on her shoes and coat and ran across the alley.

When Ardelle stepped inside, she saw Janet on the floor, one hand to her chest, the other nearly detached from her arm. "Grandma, he's down there," Ashley said. Ardelle looked down the stairs and saw Jim lying in a pool of blood, a hole in his head. She could tell that he was dead, but wondered what had happened to his beard.

Ardelle called the sheriff's office. Janet asked for a pillow, which Ardelle retrieved for her. "My back hurts," Janet said. Ardelle placed the pillow behind Janet's back, then covered her with a blanket.

As Ardelle waited for an ambulance, she went to Ashley's bedroom. Just a few weeks earlier, after Thompson had driven by Ardelle's house and glared, Ashley had locked the windows and said, "You know what, Grandma? We need to pray for Curt. He doesn't have anybody to love him." Now Ashley's socks were soaked in blood. "Let's kneel and pray for Mommy because I think she might make it," Ardelle told her granddaughter. Then she noticed that Ashley had started to pack a suitcase of clothes because she knew she wouldn't be staying home that night.

Lights still flashing, Thompson drove the now-damaged squad car west to the intersection of Commercial and Franklin Streets. There, he spotted a pickup truck being driven by his young neighbor Jason Rice, with whom he purportedly had been feuding. According to the indictment, Thompson rammed the pickup. Rice, believing he had been struck by a deputy, approached the squad car to offer help. Thompson pointed the shotgun. Rice ran from the scene.

At the Giesenhagen house, Ardelle still waited for an ambulance as Janet clung to life. It had been, by her estimation, several minutes since she had called the sheriff's office. She called again. "I need help now!" she told the dispatcher. "Where is the ambulance?" Ardelle says the dispatcher told her, "You have to call it yourself." Incredulous, Ardelle found the number to the local ambulance, located just blocks away, and called. Ardelle believes "at least" 15 or 20 minutes passed from the time she first called the dispatcher until the ambulance arrived.

By now, calls for help had been broadcast to officers in two other Stark County towns—Wyoming (six miles away) and Bradford (15 miles away). Sources say that the Toulon city policeman, Bob Taylor, was not on duty, but he raced to the scene upon learning what was happening.

Thompson was now pointed south on Franklin Street. Backup law enforcement was still minutes away. One witness says that Thompson approached another house, this one belonging to Joe Tracy, Jim Giesenhagen's best friend.

As Thompson drove past Tracy's house, Tracy's telephone rang furiously inside. By now, friends and family had heard word that Thompson had done something terrible, and they were desperate to warn Tracy. The phone kept ringing. Tracy and his wife had eaten dinner at the Barn House in Kewanee that night, and had stopped to talk to Joe's stepdaughter. Their house was empty.

By about 8:15 p.m., squad cars from Wyoming and Bradford, along with Bob Taylor in the Toulon city police car, had converged, sirens blaring. Thompson turned east on Thomas Street, then south on Miller Street, lights still flashing. He was within a block of his own house, where the slain deputy still lay.

The Bradford policeman, driving north on Miller, came head to head with the stolen squad car. Thompson stopped. The Wyoming and Toulon cars, which had gone first to Thompson's house, now came racing around the corner onto Miller and stopped behind the stolen vehicle. Thompson was surrounded.

The police aimed their weapons at Thompson. Still seated in the deputy's car, the indictment alleges, Thompson reached for a shotgun and fired through the windshield at the officers. The officers returned fire. Then, nothing moved. The only sounds in Toulon that moment were the officers' heaving breaths, and the whine of distant sirens racing to save the town.

Then more shots rang out, so many and for so long that some, describing it afterward, would liken it to the grand finale of a fireworks display. Then, another, longer silence, this one crushing in its implication—it was time for the officers to approach the stolen vehicle.

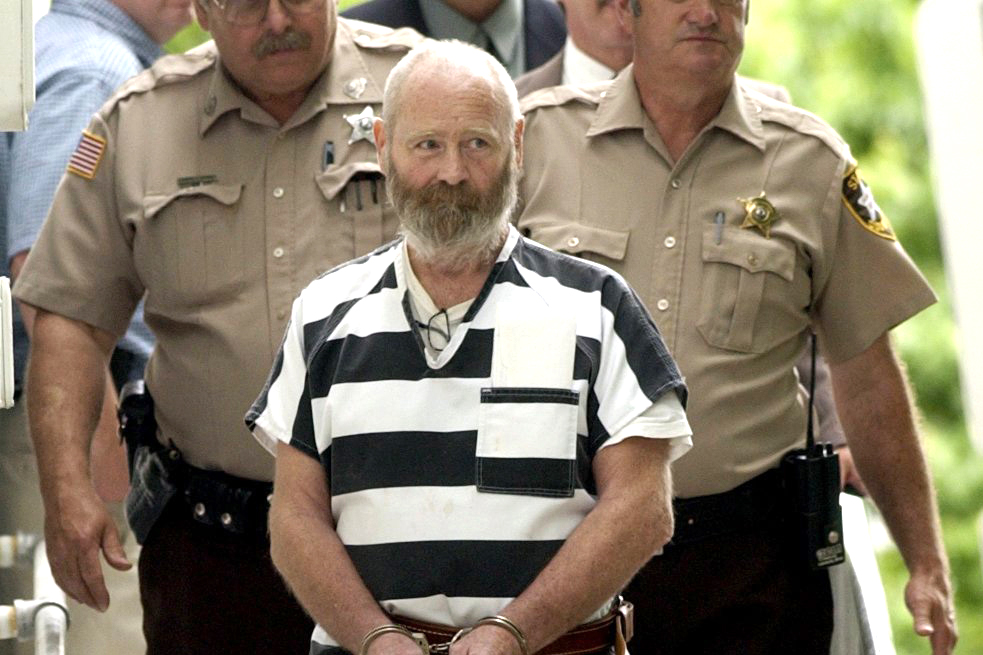

The police moved in, their lives thrust up against the crescendo of a 30-year rage. Nothing moved inside the squad car. They stepped closer. Toulon's lone traffic light, blinking a block away on Main Street, lit the scene in uncertain yellow. Thompson had been shot in the face. He appeared unconscious. Police dragged him from the car, handcuffed him, and continued to point their service revolvers at him. A medevac helicopter landed on the nearby high school football field and airlifted Thompson to a Peoria hospital.

Janet Giesenhagen was rushed to the same football field, where a helicopter awaited. She was pronounced dead on the field. That night, ten-year-old Ashley took her suitcase and slept at her grandmother's house.

Thompson was placed on life support at OSF St. Francis Medical Center in Pe-oria. His condition improved over the course of the next week. On April 1st, ten days after the murders in Toulon, he was transferred to the Peoria County Jail, and placed in a cell by himself. A few days later, he appeared in court in Toulon and demanded to represent himself, saying his court-appointed attorneys in previous cases had not been "worth throwing back." He finally consented to a public defender—Matthew Maloney, an attorney certified to handle capital cases, from Princeton, Illinois, northeast of Toulon.

There are people in Toulon—and they do not make themselves loud or visible—who knew another side to Curt Thompson. They speak of a farm boy who lost his father at an early age, who had to work for room and board in grade school, who was bright and well read and married a lovely woman to whom he stayed married and with whom he produced three children. They know that Thompson will be remembered in Toulon as a monster. They say they will remember more than that.

"Curt was probably born 100 years too late," says one of Thompson's neighbors. "He butchered his own meat. He lived frugally and was a very intelligent person. He knew the biology of livestock and was well read in politics and life events. He was very capable. I would have hired the man in an instant if not for his temper."

"If you needed anything, Curt and his wife would come," recalls Mary Jane Swank. "When I came home from the hospital, they fixed us a complete meal, and I mean complete: chicken, pork chops, corn, potatoes, everything. Just a few days before [the shootings], Curt brought us some meat he'd butchered.

"I knew he had problems with people. But if anyone treated him fair, he'd treat you fair back. Curt had so much to give—that's the part that hurts me a lot. If he was treated decent . . . you know how small towns are—they have to pick at somebody and never let up."

"I felt bad for him sometimes," says a friend of Thompson's. "He never drove a fancy truck. A lot of his life was spent not having more than minimum finances. He always had two big black Lab dogs—salivated all over, but very nice, never growled or snapped. He'd bring the dogs along sometimes. About ten years ago, I noticed that he had only one of the dogs. He told me he had to put the other dog to sleep because it had heartworms. I asked if heartworms couldn't be treated. He said, 'Yeah, you can treat it, but I did not have enough money.' You should have seen his face. I thought he was going to cry. To me, it showed that he had a heart like anyone else."

Shortly after Jim and Janet Giesenhagen died, Toulon united to throw several fundraisers for Ashley. In a candle sale, citizens collected $3,500 for her future education. It had been the kind of gesture instinctive to the town since before Lincoln's speech on the courthouse lawn.

When asked about Thompson, many in Toulon do not want to talk. They are polite about it, all of them. And they are consistent in their reasoning.

"I don't want to think about it," one resident says. "I wish this would all just go away."

A month after the murders, Curt Thompson was taken to the Stark County courthouse to enter pleas in the 30-count indictment against him. Under heavy guard and wearing an old-fashioned gray-and-white-striped prisoner's jump suit, he walked deliberately into the courtroom, making eye contact with no one. Ashley Giesenhagen, seated in the back of the room, began sobbing at the sight of Thompson.

As the prosecutor read the indictment, questions wafted out the open courtroom window, through Toulon's two coffee shops, past Casey's gas station, and into the fields that frame Stark County. Why hadn't the sheriff's dispatcher called an ambulance immediately? Why had a rookie deputy tried on his own to serve a five-month-old warrant on a Friday night to a man known to be violent? Why hadn't law enforcement prosecuted Thompson if he had violated court protective orders? Had police been afraid of Thompson? Had the state's attorney done enough to stop him?

And, most important: Had the beauty of small-town life—that shoulder-to-shoulder proximity to everything and everyone—become its ugly undoing?

Thompson, through his lawyer, pleaded not guilty to all charges. The proceedings lasted about 30 minutes. After he was unshackled from a table, Thompson walked toward the door as he had entered—slowly and without expression. Just before leaving, he turned briefly toward the public who had packed the courtroom, and stared.

Update: Six years later, Thompson died in prison in an apparent suicide.

Comments are closed.