The faintest whiff of eau de skunk had just pricked my nostrils when Rick Wilberschied, moving with the deliberation of an explosives expert sweating over a ticking time bomb, waved me over to him, a finger to his lips.

The setting was the back porch of a lovely home on the lovely White Deer Run golf course one lovely sunny June afternoon in Vernon Hills. Wilberschied, whose job is to trap rogue critters stirring up mischief in the urban veldt, had been summoned to investigate a family of skunks that had taken up residence under a concrete stoop at the back of the home. A few days earlier, Wilberschied had scouted the location and set two traps. The bait had been a tried-and-true blend of 11 herbs and spices that Wilberschied—a.k.a. the Critter Hunter, a.k.a. Dog the Bounty Hunter of the nuisance wildlife business—had hit upon during hours spent plying the fast-food byways of suburbia: the three-piece wing meal from Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Until that moment, I had been more than happy to loll in the warm sun, alternating my attention between Wilberschied girding for battle—pulling on leather gloves, grabbing a roll of duct tape, tearing a couple of plastic trash bags from the box—and a lively foursome of elderly women in visors and white skirts cackling over a missed putt a couple of hundred feet away. Suddenly, however, the winds shifted, and Wilberschied, straightening like a pointer, headed for the traps.

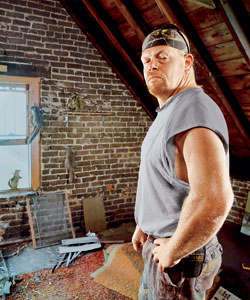

Wilberschied, 42, cut an incongruous figure in this suburban milieu of twittering birds and retired duffers. He wore jeans, thick-soled Skechers work boots, a do-rag with a wildlife camouflage print, and the kind of orange-tinted sports shades favored by macho cops and baseball outfielders. His long strawberry-blond hair spilled onto his shoulders and was only slightly lighter in color than the faintly reddish hue of his goatee. At six feet two inches tall and 238 pounds, he looked like Hulk Hogan minus the perma-tan, a reality show waiting to happen. He also looked like he knew what he was doing, a fact for which, at that moment, I was deeply thankful.

"Check this out," he said, tilting one of the traps on its end. "You see that?" I leaned over and looked. Staring back at me was a small black haunch. A butt, to be more precise. A puckered butt. An angry butt. Not to put too fine a point on it, but it was a sight to give one pause.

Only slightly less dismaying was the faint leer Wilberschied wore as he whispered, in the hushed voice of a TV golf announcer, "You know what that's called?" I shook my head as a sharp and bittersweet aroma, the precursor to a hot blast of skunk essence, I later learned, began to leak like radioactive material. "That," Wilberschied said, "is a little thing we refer to as 'cocked, locked, and ready to rock.' "

* * *

|

Rick Wilberschied should know. As a man who makes his living from restaurants, churches, water parks, college campuses, hotels, offices, and human habitats of the two-garage variety, ridding them of critters that go bump in the night—and day—one of his most memorable moments, in a career full of them, was the time a skunk blasted him full in the face. "We had a bunch of traps set out on this golf course," he explained to me one day. "And we caught this skunk right on the driving range. He was a little firecracker. I got about 20 yards from him when he started posturing, stamping his feet. That's a bad sign. It means he's about to blow. So I'm like, OK, we got one with a bad attitude.

"So I filled a syringe pole with a cc and a half of this juice to calm him down, stood the cage up on its end, and went to push the needle in. As I did, he spun ass up in the air. I broke my needle off in the ground, and the next thing I know, I just see yellow liquid come flying up out of the cage like something out of a sports drink commercial where you see sweat flying in slow motion. When I saw it, something in my mind goes, You are so screwed. And then this cloud hit me, right in the face. I had my sunglasses up on my head. No do-rag. Caught it right square in the eyes."

"My God," I said. "What was that like?"

"Imagine somebody putting habanero sauce on their fingertips and jabbing them in your eyes. Let's just say . . . it's a drag."

I remembered all of this as I stared down at the angry skunk butt that day, on the lovely stoop in the lovely environs of Vernon Hills. It came to me, in fact, just about the time I realized that the skunk in the cage was stamping his feet.

Photograph: Ryan Robinson

* * *

Take a ride with the Critter Hunter :: Launch the slideshow

The first thing you need to know about Rick Wilberschied is that he punched a bear in the face. The second is that the moment was not all that remarkable, at least not to him.

Of course, he has a rich portfolio of bizarre critter tales from which to draw. Such as the Maggot-Dripping Raccoon, a corpse he pulled from the chimney of a bridal preparation suite. ("Maggots everywhere," Wilberschied recalls. "Fat ones. Thin ones. Raining down all over me, in my hair, down my shirt. One of the guys standing next to me was gagging. All these girls hanging out with maggots all over the place—good times!") Or Snakes on a Plane, in which Wilberschied—channeling Samuel L. Jackson—found himself chasing a group of zoo-bound rattlers that had slithered out of their crates and into the cargo hold of a parked jetliner. (The passengers, fortunately, had departed.) Or the Flying Raccoon. In that instance, Wilberschied received a 3 a.m. call to rescue a family from a raccoon that had broken through the ceiling. The creature, shrieking and clawing, had dropped into a crib occupied by a blissfully slumbering baby.

"The kid was looking at the 'coon, and the 'coon was looking at the kid," Wilberschied says. "The parents grabbed the child, ran out the door, and locked it." The baby was fine, he says. The father was "screaming like an eight-year-old girl who's torn her Easter dress."

* * *

|

It's a jungle out there. Or, rather, in here. In the city. In the suburbs. In schools, churches, cafés, nightclubs. Bats, rats, bees, fleas, raccoons, opossums. Snakes on a plane. Foxes in the henhouse. Bambi in the backyard. Gophers on the greens. Urban coyotes. Suburban cougars. Ducks, mice, moles, voles, woodchucks, chipmunks, bunnies, hedgehogs, and squirrels. To name a few.

They are wild and they are hungry and they want in. And their numbers are growing. In 2006 alone, Illinois nuisance wildlife operators like Wilberschied caught 16,000 raccoons, 15,000 squirrels, 5,000 striped skunks, 6,000 opossums, 1,200 muskrats, 300 coyotes, and too many bats and birds to count. Since 1992, the number of reported wildlife problems in Illinois has almost tripled—from 36,000 a year to more than 92,000.

Experts say the lack of natural predators, shrinking habitats due to hyperdevelopment, and, above all, the presence of a running blue-plate special account for the perfect animal storm. "First of all, they have all the food they could ever want," says Bob Bluett, a wildlife biologist with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. "You can go into the Dumpsters behind TGI Friday's. You can go into somebody's garbage cans, or dog dish. You can pick up June bugs underneath streetlamps.

"Then, they have all these comfy places to live—attics, basements, stoops." Finally, you have residents who not only tolerate the critters, but feed them, nurture them, treat them like pets. The result? Fifty-eight percent of respondents to a 2001 survey of Illinois homeowners reported having repeated problems with wildlife—from digging to burrowing to scattering garbage to moving in.

The problem is not confined to the United States. In Kathmandu, Nepal, a group of monkeys invaded the Indian Embassy, attacking embassy officials, defecating in offices, and destroying equipment. In India's Parliament complex, monkeys ransacked files, screeched at visitors, and banged on office windows. In parts of Canada there have been so many "nuisance bear" incidents that the sight of a black bear picking through the garbage barely raises an alarm. Closer to home, the Chicago area has experienced numerous problems with coyotes, and more dramatically, the case last April of a cougar running loose on the North Side. The animal was eventually shot and killed by police.

Nationwide, wildlife mischief has been blamed for more than $22 billion a year in damage to homes and property. Earlier this year, a single skunk drove a Highland Park family from their five-bedroom home. The family first noticed the smell in April 2007 after returning from vacation. At first, they dismissed it, but the stench grew worse by the day. Soon, one of the children was being called Skunk Boy at school, according to the Chicago Tribune. Dr. Alan Hirsch of the Chicago-based Smell & Taste Treatment and Research Foundation described the smell to the paper as "putrid, sewer-like, musty, swampy, musky, uriniferous, and stale." The odor, he said, "was like being slapped in the face."

Still, some people argue that humans, not animals, are the invaders. "If greedy developers would stop building strip malls and condos, maybe the wildlife wouldn't have to come in contact with humans," wrote one poster to an online forum on the rise in nuisance wildlife problems in Florida. Even the owners of the Highland Park home that suffered so much damage had a soft spot for the skunk run amuck. When asked about the critter by the Tribune, one of the owners allowed that it "was actually very cute."

Most people, however, are far less sanguine, especially when the animals sneak into homes, gorge on prize petunias, and squat in attics.

When that happens, they call Wilberschied.

His fees vary, depending on how far away the job is, what kind of critter he's up against, and whether he's forced to hand-capture the animal or simply set a trap. Babies cost extra, as do cases involving hand-to-paw combat, depending on how bad and bloody the fight.

Watching Wilberschied work is like watching a master deep-woods tracker. He sees things the rest of us don't. On one call, a puzzled homeowner with a squirrel problem said he couldn't imagine how the critter had slipped into his house. Wilberschied walked right up to a spot under an eave and pointed at a small sliver of a crack, surrounded by tiny, almost imperceptible scratch marks. The homeowner, astonished, shook his head. "I had no idea they could get in through a space that small." At another site, I was busy looking at the roof of a house when Wilberschied cast a glance at the lawn. He indicated several nearly invisible bulges in the turf. "This guy's got serious mole problems," he said.

* * *

Slideshow: Esther Kang

Photograph: Ryan Robinson

Wilberschied's Chevy Silverado four-by-four holds his gear, baits, and tools and blasts Mötley Crüe.

|

The sign at the entrance to the football field at Concordia University in River Forest calls the small stadium the "Home of the Cougars." But of late, it's been the domain of a fox. "He's peed on the carpet," Linda Holowicki, the director of the physical plant, tells Wilberschied as she leads him on a tour, pointing to the artificial surface of the field. "He likes to sit under the stands or over by the cafeteria. You see that little mud pile? One day he sat there all day, just scratching himself," she says. "The last week of school, he was eating a rabbit in front of the cafeteria. Our football coach tried to hit him with a football one time, but he missed."

The fox's audacity is emblematic of a growing lack of fear among urban and suburban wild things. "In the wild you couldn't get within 200 yards of a fox," says Wilberschied. "This one is so brazen you could almost pet him. The thing is, all it takes is for one person to start feeding them, and all those natural inhibitions go out the window because there's a free meal around."

"Have you seen him today?" Holowicki asks a passing student.

"Not yet," the student says.

"You see?" Holowicki says. "Everyone here knows him."

"Have you, by any chance, been able to see the plumbing on this animal?" Wilberschied asks. She shakes her head.

"Well, the fact that it's hanging out here tells me that it's not a he, but a she. Probably a mother with a litter somewhere that's not really big enough to follow her yet." Wilberschied cases the campus and finds a few rabbit bones, a skull—leftovers from a feeding. "See? She eats these and then goes back and regurgitates them to her young."

As Wilberschied is talking, a rusty mini truck with the words "King of Trash" spray-painted on the side pulls up. The King is actually a maintenance worker who wears dirty sweatpants and a gray T-shirt. "We've been trying to catch him," the King says. Wilberschied climbs a ladder onto a platform and peers into a large garbage bin. He pulls his mirrored shades up onto the top of his head and looks down at the King. "Do me a favor," he says. "Don't. You don't want to go messing around with a wild animal."

Wilberschied makes one more trip around the campus. Sly fox. She picks today to make herself scarce. "Well, call me if you see her again," he says. "If I can actually get from me to you, I can try to noose the animal. If I can't, the next thing to do is dart it. I've got a dart pistol—just let security know. Not too cool to be showing up with a gun on a campus these days."

* * *

Having professionally trapped for three years, Wilberschied is a relative newcomer to the nuisance wildlife animal business, but he's been a lifelong student of critters. "Pretty much from the time I was old enough to walk I was trapping and fishing and hunting," Wilberschied tells me as we drive to the day's next stop, a squirrel complaint in Hoffman Estates. "My dad got me and my two other brothers into the outdoors."

It was on a family bow-hunting trip, in fact, that Wilberschied's heavyweight bear bout occurred. "I was in northern Minnesota, hunting with my brother," he recalls.

He was waiting in a tree when two cubs smelling bait ambled up right below him. "I pulled an arrow out of the quiver, turned it around, and bopped one on the head," he says. "He let out a little 'Rahhh,' and pretty soon, Mom is coming to the rescue. She got to the bottom of the tree and started popping her jaws and woofing. Now, you have to remember that bear can climb a tree the way a squirrel can, like somebody launched them out of a cannon. So when she started up, I reached down and punched her in the nose with my fist. Fortunately, that was enough for her, and she wandered away."

* * *

For the Wilberschieds, who lived in a bungalow near the corner of Addison Street and Harlem Avenue, catching critters wasn't a matter of recreation—"It was a way of life," he says. "My dad and uncle would go down to Montrose Harbor during smelting season—they'd come home with, like, five-gallon buckets, loads of them. They'd clean them up; then my mom would flour them and fry them right there."

"I was raised on rabbit," he says. One of Wilberschied's earliest memories, in fact, was catching bunnies in wire snares he strung across paths in the woods near his home. "For a lot of people [catching dinner] was a novelty," he says. "For us, it was living."

After attending Prosser Vocational High School, Wilberschied went into his father's line of work, construction. "It pretty much tore me up," he says, referring to the assorted injuries he sustained. "Makes it fun trying to climb around attics and on the roofs of three-story houses." He later upholstered himself in a coat and tie and sold construction supplies. "Every morning I woke up and I just hated going to work," he says. "It just sucked. I wanted to be one of those people who could get up and be pumped up about the day. I couldn't stand being behind a desk." One day, he says, a friend who was a bricklayer told him about a job working with nuisance wildlife. "He said, 'You hate doing what you're doing—why don't you come try this?' I knew immediately that I'd found something I could really enjoy doing."

He started out working for another operator. Then three years ago, he formed All That's Wildlife, which he advertises at AllThatsWildlife.com. He was a natural. From his childhood, and years of self-guided study, he had an almost preternatural ability to find and trap animals. As with all commercial wildlife operators in Illinois, he had to pass a rigorous licensing exam that requires extensive knowledge of wildlife diseases and symptoms, mastery of the proper way to capture and dispose of animals, and the ability to recognize species and their habits. Today, he is one of about 330 licensed wildlife operators in the state.

* * *

|

Wilberschied, however, is a critter of unique habits. He arrives like an action hero, in full fatigues and his trademark wildlife-print do-rag holding back his rock-star long blond hair—Dr. Doolittle as pro wrestler. He speaks simply and directly, his voice a deep rumble inflected with a Midwestern twang. He lives on ten acres near Harvard, a place that provides not only an escape from the stresses of 15-hour days, but also a small wildlife kingdom in its own right. If the critters are small enough, say a squirrel or a chipmunk, he'll even release animals he's trapped onto the grounds.

He realizes he cuts a rather unorthodox figure but believes his appearance and, more important, how he carries himself instill, not diminish, confidence. "There might be some people who are a little taken off guard at first, but most people who see me realize, 'This guy knows what he's doing.'"

Polo shirts and creased khakis might look nice, he says, but they're not real practical when wrestling a diarrhea-happy raccoon. "I'm watching this reality show with guys who kind of do what I do," he tells me.

"These guys are in, like, a nice button-down shirt, with brown slacks or cords, and some nice shoes, loafers or some nonsense. Completely robotic. I'm like, 'Are you kidding me?' You're not going to catch me in anything like that."

He once responded to a call to extract a "few" bats from the attic of a condo in the northwest suburbs only to find himself facing a 1,400-bat shitstorm that had him plucking guano speckles from his hair all night. Another time, he dislodged an under-eave hive of bees so big it looked like the creature's lair in the movie Aliens. ("It was fine," he says. "I only got stung 20 or 30 times.")

"I'm dirty and sweaty on a daily basis," he says. "When I've gotta pull a dead raccoon carcass out of a wall with maggots spilling all over me, a white button-down shirt and khakis ain't exactly the ideal uniform."

* * *

Some critters go quietly. Others provide 12-round epics. On one call, Wilberschied found himself trying to evict a raccoon and her babies from an opening in the roof of a home in Barrington. The roof was steeply pitched and slick, from being freshly washed—"like standing on a toboggan run with no poles," Wilberschied says.

Unable to shoot her with a dart gun, Wilberschied loaded a syringe pole. "Now, you've gotta remember: A raccoon can grab something like you and me can grab something," he says. "So while I'm trying to spin her around, she grabs ahold of the needle and rips the syringe off and throws it down.

"We look at each other and now I'm like, OK. So I try a noose pole. I'm holding on with one knee and Momma starts nipping me. I stick the pole in there and she lunges out. I start smacking her in the face with the back of my hand. The next time she dives through the loop and I'm able to cinch her up.

"So I pull her out, and now I've got a 15-pound female bouncing around fighting me, and I'm trying to hold on to this roof to keep from sliding down 30 feet, and going off the roof with her in tow. I wrestle her into a trap on the roof, but now I've got to go back to get the babies. The first time I shove my arm in I take a rusty nail right in the bicep, and, I mean, it was like a rusty hypodermic needle. I pull it out of my arm, but now I'm bleeding like crazy. Meanwhile, I got raccoon shit all over me from Momma, who now has diarrhea, and I'm just, like—you know, this is an interesting job."

* * *

We drive. Hoffman Estates, Schaumburg, Oak Park, Vernon Hills. Elk Grove Village, Bensenville, Barrington, Bartlett—his territory ranging from Lake Geneva to the south suburbs, from the lake to DeKalb. Wilberschied estimates that he puts 200 to 300 miles a day on his rig, crisscrossing the collar counties, dipping into the city, checking traps, setting traps, listening to the stories of beleaguered homeowners kept up all night by critters skittering across their ceilings, flapping in soffits, chattering through the walls like noisy neighbors in the next apartment.

His truck is serious—a big black Chevy Silverado four-by-four. Gassing up the thing is a bitch—he spends about $500 a week for fuel. But as the saying goes, he practically lives in it—or spends 15 hours a day in it—so he chose a vehicle that would be comfortable for his big frame. The side panels flip up to reveal compartments containing a large flashlight, extra gloves, paper particle masks, noose poles, a syringe pole, and dart poles. There's a "snake cam," a flexible sheath that allows him to thread a camera into basements in search of hidden critters. There's "eviction fluid"—a stinky concoction designed to mimic the smell of an offensive male raccoon that's sprinkled in an attic, say, to encourage a mom and her babies to pick up and go. The truck also carries small vials of a euthanasia agent, a proprietary blend he calls "nighty-night," administered through a syringe pole.

For the longer trips, Wilberschied relies on the Chevy's high-end stereo system, through which he blasts eighties metal like Mötley Crüe and AC/DC.

He tapped a company called Road Rage Designs to trick up the outside, to make it a rolling billboard, and they did: The truck is dotted with paw-print decals, a big logo sign that says "All That's Wildlife," and numbers to three cell phones that are always on. Some people smile. Some roll their windows down. "Hey, what are you trying to catch?" On our way to one call—a raccoon clan in a basement—Wilberschied notices a couple of gawking teenagers. A moment later one of his phones rings. Working a toothpick in the corner of his mouth, Wilberschied shoots me a sidelong glance. "Kid says his friend wants to be an animal bounty hunter, like me."

* * *

The Arsenal: Wilberschied's truck carries his critter-hunting tools. Here are a few: (1) The syringe pole comes in handy with animals trapped in spots where they can't escape, say, a window well. It is also used to inject animals already in a trap. (2) Bazooka Joe is a bait that does indeed smell like bubble gum. Used primarily to attract raccoons, it can be slathered on a stick hung in a trap or smeared on the bottom of a cage. (3) The noose pole is used in certain live-capture situations (instead of a trap), such as when a raccoon pokes its head through an opening. ("You can't just reach your hand in there," says Wilberschied.)

He's called to pull a bird from a church wall. He's summoned to catch a squirrel with a sweet tooth that's been raiding a water park concession. ("It was breaking into the food supply," Wilberschied says. "They called me when they saw it run by with a PayDay in its mouth.") There have been celebrity homes, including those of a couple of major sports figures and even a rock star. (Wilberschied asked that I not reveal their names.) He's often called to golf courses to hunt gophers and woodchucks, gigs that are virtually guaranteed to elicit Caddyshack shtick from the people who hired him. ("If I had a nickel for every Bill Murray imitation I've heard . . . ," he says.)

In the Midwest, early spring to early summer is the season of the raccoon. Female raccoons give birth only once a year and their search for a place to raise their pups can become urgent. Attics and basements are favorite squatting sites. "They're warm, they're out of the elements, and there's often good food sources around," Wilberschied says.

The problem is, the animals tend to poop and pee a lot. And scratch and claw. And chirp and chatter. And, when cornered, attack.

One afternoon, I was feeling sorry for a raccoon that Wilberschied had loaded into his truck. She seemed so mellow. She fixed me with her black-ringed burglar's eyes. She twitched her nose. Awwwww.

Wilberschied understood. "They go a couple of different ways. They can be really mellow like her. Or they can be like terrorists, nothing but muscle and attitude, and everything in the world to back that attitude up."

The truth is, raccoons have up to 600 pounds per square inch of bite pressure in their jaws—a German shepherd has about 900—and "claws that can slash a piece of thick boot leather," says Wilberschied. "I've had 'em where they've reached out through the cage and just slashed my pants. They're like Freddy Krueger with four feet. Put a raccoon in a room with a pit bull and guess which one isn't coming out. But yeah, they are cute."

The Critter Hunter understands, then, why people get upset over what he does. "They call me Bambi killer and stuff like that, but that's OK. Thing is, a lot of people don't realize that I'm required by law to euthanize raccoons and skunks"—skunks explicitly, and raccoons for the lack of other good options. With raccoons, wildlife operators have the choice of releasing the animal within 100 yards of the property (not the favorite option for someone trying to get rid of a critter), turning it over to a vet for weeks of quarantine and release (not the favorite option of vets), or euthanizing the creature. State law requires that all captured skunks be euthanized, however, because of the risk of rabies.

The Illinois DNR's Bluett, who also describes himself as an animal lover, says the last solution is often the most humane. "It may make us feel better to let them go," he says, "but it doesn't necessarily change the outcome for the animal and may mean he is exposed to disease or, as is often the case, a car."

People don't realize that Wilberschied releases most other animals on the grounds of his Harvard home or at various release sites around the state. Or that, unlike many wildlife nuisance operators, he wraps his traps in dark plastic to shield trapped critters from the sun and gives them food and water.

"I'm like anybody else," he says. "I've got a heart and I love animals. When it comes time to put an animal down, I would rather not have to do it. But I have to follow the law, and the truth is, some of these species are wildly overpopulated. In the end, most people understand—particularly the ones who've had their children scared by an animal or their attics ripped apart. We go from Bambi killer to the ultimate superhero when something happens in somebody's house."

* * *

The baby skunks are cute, adorable even. Stinky. Three huddle in one cage. A fourth prowls in a second. The three are mellow. The fourth is pissed. It is a serene day. A bright, hot sun bakes the golf course. Carts come and go, the golfers oblivious to the delicate operation happening just a couple of hundred feet away. The owners of the house are out. All they know is that when they return, the skunks will be gone. They've left a check just inside the storm door.

In the shadow of a tidy two-story house, Wilberschied works to secure the traps. Sweat has begun to darken his do-rag as he carefully lifts one skunk cage and tilts it on its side. He moves with grace and finesse, wrapping the long rectangular wire trap in first one trash bag, then a second. Gently, ever so gently, he seals them both. The critters, as required, will be put down, in this case with a combination of carbon monoxide gas and nighty-night, then loaded into the back of Wilberschied's truck. A trap will be left behind for the mother.

Bagging the second trap, however, is not so easy. The lone skunk is clearly about to pull the pin. When Wilberschied calls me over, I think back to his golf course story, the habanero sting to the eyes. And I wonder if I'm about to have my very own "You are so screwed" moment. Still, I don't want to look like a wuss in front of the Critter Hunter, so I peer into the abyss of the cage and catch sight of the small, angry butt. For a moment, I feel a pang of sympathy. Poor wittle thing. But then Pepe begins to stamp his feet. I catch a whiff from what I realize is a warning volley. The abyss is staring back. I brace for the gas when Wilberschied steps in. Swiftly, assuredly, he slips one bag over the trap, then a second. I'm feeling a little bad for the critter, but I feel something else, far more deeply: gratitude.

Photography: Ryan Robinson