Tony Magee is singing, but on a recent weeknight the crowd at Riverview Tavern in Roscoe Village hardly notices. They are talking, drinking, watching an NBA playoff game—anything but paying attention to the disheveled middle-aged white guy who is finger-picking old blues tunes on a classic Martin. Once he finishes his last song, he puts the guitar down and stands there alone. A few uncomfortable minutes tick by.

Slowly it dawns on the bearded young men scattered about the bar that the music has stopped. One by one, they migrate toward the man of the hour, excitedly asking him for autographs and to pose for pictures. (His appearance is part of a series of Chicago Craft Beer Week events.) They may have rather watched the game than listen to Magee the Roving Bluesman, but now they’re lining up to greet Magee the Craft Beer Celebrity, founder of the renegade Lagunitas Brewing Company. “You want him to be nice—and thank God he is,” says Samuel Evans, a partner in Chicago’s startup Ale Syndicate Brewers, who’s patiently waiting.

One reason for the adulation: Even in the eccentric universe of beer brewing, Magee, 53, is as unlikely a corporate chieftain as they come. An Arlington Heights native who dropped out of Northern Illinois University to play in a traveling reggae band, he drifted for much of his 20s, eventually settling in Northern California.

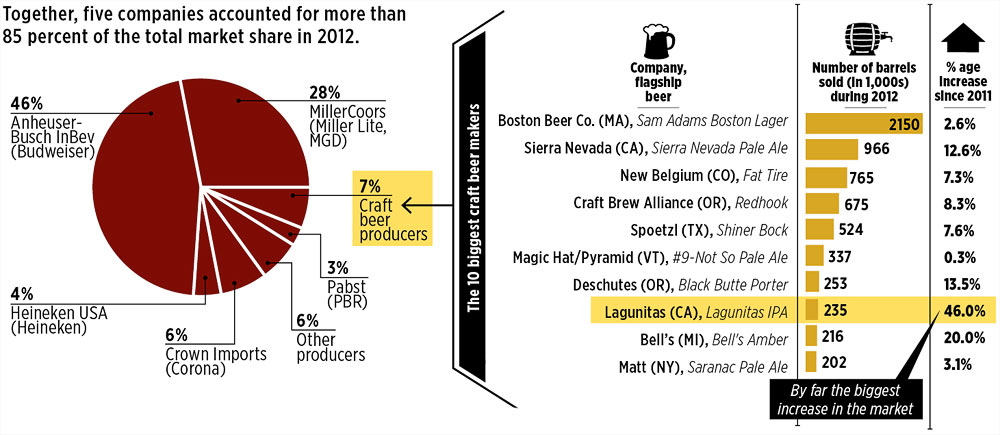

He plodded along in the printing business for several years while he tried to find his real calling. Then he saw how much fun his younger brother was having making beer at a pub in Portland. One homebrew kit later, Magee was crafting beer in his kitchen and then, in a year, delivering kegs of his own special high-alcohol concoction to bars near his house. That was 1993. Two decades later, he’s still designing his own beer labels, playing blues guitar semiprofessionally, smoking weed with his employees, and clinging to his regular-guy reputation. And he has managed to turn his company into one of the largest, fastest-growing, and most irreverent specialty beverage makers in the country, with $65 million in revenues in 2012, Magee says. From 2011 to 2012, the number of barrels shipped—a key metric in the beer industry—rose 46 percent, more than double the growth of any of the top 10 U.S. craft breweries (see chart below), according to the trade group Beer Marketer’s Insights.

Magee is determined to become a threat not only to the industry’s two Goliaths, Anheuser-Busch InBev and Chicago-based MillerCoors—which together account for nearly 75 percent of the U.S. market (see chart below)—but to any beer company that he deems as operating under less-than-pure ideals. “Craft is like porn,” quips Magee. “You know it when you see it.”

As the demand for more robust American beers grows, and as the beverage regulation laws become friendlier to startups, Magee suddenly finds himself surrounded by an explosion of professionals—and hobbyists—who can produce unique ales that rival those of the original maverick craft producers like him. The one thing no one seems able to replicate is, well, Tony Magee himself, a plainspoken Everyman whose rebellious personality has become inextricable from his brand. Lagunitas remains a quirky family enterprise, controlled not by stockholders or venture capital firms but by its founder, who retains the majority interest and isn’t shy about flaunting it. (Individual investors include the company’s Petaluma landlord and a local veterinarian, but they own small shares, says a company spokeswoman. And while there is an advisory board of three, it has no voting power.)

“Well, I control the company, you know?” he declares. “So it’s pretty simple like that. It’s not like there’s all sorts of investors who have some idea that they want things to be different. Those guys are pretty demanding and unforgiving, and you don’t mess around and take adventures with their money. But for us, it’s not like that at all. We just do stuff. We want to be smart, and careful, but once something seems clear, it’s usually pretty clear.”

For example, last spring he used his rambling, uncensored, and thus wildly popular Twitter account to announce to his 15,000 or so followers that he was “gonna make a little bit o’ NorCal right there in the City of Chicago.”

Fast-forward to 2013: Magee is laying the foundation for the largest craft beer empire in the United States by developing a 300,000-square-foot complex on an industrial stretch near 16th Street and Western Avenue in North Lawndale. The facility, which should be fully operational by March 2014, will have an initial capacity of 600,000 barrels, though it will take a few years to ramp up production to that point. That’s more than the output of all the other Chicago craft breweries combined, according to analysis of a recent report from the Colorado-based Brewers Association, an independent trade group.

“I’ve spent 20 years holding back the reins but always feeling like the horse would go crazy if I just let it,” Magee confesses. “This is the first time we’re going to let the reins forward.”

That’s exhilarating and a little scary, both for Magee and for fans of the craft beer scene, which is known for its small, independent producers as much as for its hoppy, adventurous beers. And while Magee’s plans appear to conflict with a core tenet of the craft scene—that scrappy little breweries are awesome and big corporate breweries are not—enthusiasts of flavorful beers with ironic titles and offbeat labels seem willing to give Magee a chance.

“If somebody [from craft brewing] is going to get really big and become a pillar of big brewing in this country, then [Lagunitas] are the people you want to win,” says Gabriel Magliaro, founder of Half Acre Beer Company in Lincoln Square. “If Tony’s at the helm, I think it’ll probably stay weird on some level.” That endorsement also points to the greatest challenge facing Lagunitas: to maintain the brewery’s freewheeling culture and reputation while operating at a scale that more closely resembles that of Big Beer.

Magee doesn’t have an office at the Lagunitas facility in an industrial park in Petaluma. He prefers to rove as a “ghost in the machine” in his complex, which consists of an administrative office, a 300-seat brewpub, and a massive brewing operation. (All together, Lagunitas employs about 300 people across the country.)

He’s delegated much of Lagunitas’s day-to-day business to his chief operating officer, Todd Stevenson, and his chief financial officer, Leon Sharyon, in much the same way that he handed over the actual art of beer making to his brewmaster, Jeremy Marshall, five or so years ago. With his ponytail, chin beard, relaxed vibe, and droll wit, Marshall is more reminiscent of a Deadhead than a master engineer.

“I’m good at getting out of my own way,” says Magee. “Brewing takes repetition—and if I were a kid today, they would spray me with Ritalin from a safe distance.”

Yet he himself crafted the raw, hop-heavy India pale ale that put Lagunitas on the map in 1995 and remains its flagship. At the time, the closest major craft brewery, Sierra Nevada, had the market cornered with a light, drinkable American-style pale ale that nearly every California craft beer bar kept on tap. Demonstrating his talent for marketing, Magee decided to stand out by brewing a bolder, more aggressive style—the then-unfamiliar IPA—which smacked bar patrons in the taste buds and has since emerged as the calling card of upstart breweries across the country (to read about the new crop of Chicago IPAs, see “The Best Beer in Chicago”).

But in more recent years, the only year-round, mass-production Lagunitas beers rated “outstanding” by the influential publication Beer Advocate have been Marshall’s creations: the New Dogtown IPA (score: 90 out of 100); a bitter, spicy IPA called Hop Stoopid (score: 94); and the fruity, sweeter pale wheat ale Little Sumpin’ Sumpin’ (also a 94), which popped up in the Chicago market in 2008 and soon became a popular addition to local draft menus.

Magee remains very much in charge, partly because he knows the name of almost everyone who works for him, thanks to his nomadic management style, and partly because he demands some input on everything. He still writes free-verse beer labels—every bottle of Maximus Ale, Lagunitas’s year-round Imperial IPA, for example, bears this psychedelic musing:

“I leaned back with my feet up on my desk. I read my name backwards on the door and wondered. Like a bad joke told to a brown-shoed square in the dead of night, it all came back to me. I thought carefully about getting up from my desk, putting on my new Velarimosa prawn hat, opening the door to the hallway, checking the spelling on my name one more time, closing the door behind me, heading down to the first floor, making my way down the evening street full of worn out proles and pinheads, finding the corrupt pirate pastrami burrito vendor who trades fist fulls of change for volcanic gastritis, continuing to a dark doorway the length of which would lead me to a knuckle worn bar top of mildew and pine, mounting a bow-legged stool and ordering a pint of the nectaral Maximus Ale. And then I did.”

True to form, the plan Magee devised last fall to take over the world of craft beer was hatched not in a boardroom but after a “wake and bake”—getting high before making the half-hour drive to the brewery through the rolling hills and vineyards of Sonoma County.

That morning, his wife, Carissa Brader, a Downers Grove native who’d met her future husband in a music class at Northern Illinois, stood at the bathroom sink in their ranch-style home in the woods of Point Reyes Station and complained about the high costs of sending beer to Chicago, New York, and other markets back east. Brader oversees shipping for Lagunitas, and she projected that the company would have to spend $140,000 a month in 2014—$1.68 million for the year—to ship beer to markets east of the Rockies.

During his commute, Magee experienced an epiphany: If he could land a bank loan, he could rent a complex in an industrial area of his native Chicago and equip the facility with the same gleaming state-of-the-art mash mixers and fermenters used in his Petaluma headquarters. The Chicago brewery (estimated price tag: $22 million) could serve as Lagunitas’s eastern base of operations—and the monthly rent would roughly equal what he was spending every month on shipping. “It would be practically free,” Magee reasoned.

The new facility positions Lagunitas for massive growth, but it won’t happen overnight. Last year, the company sold just under 250,000 barrels, making it the 13th-largest American brewer by sales volume, according to the Brewers Association. But once the Chicago facility is running at its maximum capacity (there are plans to add a second brew house), Lagunitas could eventually produce a whopping 1.7 million barrels a year.

But for all Magee’s talk about racing Lagunitas like a thoroughbred, he won’t brew more beer until the market is ready for it. He lived through the first craft beer bubble in the 1990s, when a slew of upstarts flooded the market and then folded. “People didn’t stop drinking craft,” he explains. “Supply just exceeded demand.”

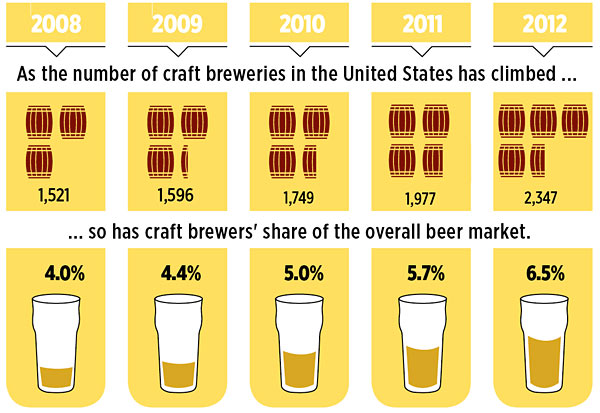

The craft beer market ultimately recovered—and since the mid-2000s, craft beer production has zoomed (see the “Hop, Hop, Hopping” chart at top). In 2012, $10.2 billion of the $99 billion that Americans spent on beer went to craft purchases, according to the Brewers Association. The group strictly defines “craft” as an operation that is small (an annual production of less than six million barrels a year) and independently owned (a big brewer can’t have more than a 25 percent stake).

The competition is fierce. Last year, some 300 new microbreweries and 100 brewpubs opened in the United States, bringing the total count of craft beer enterprises to nearly 2,400. Meanwhile, two of the biggest players, Colorado’s New Belgium Brewing Company (maker of Fat Tire) and Sierra Nevada, have announced that they, too, are ramping up their production capabilities: Both are building facilities in North Carolina, giving each an East Coast presence.

The dramatic uptick in capacity “will skyrocket them to the next level,” says Christopher Staten, beer editor of Draft Magazine. But he warns that “there’s definitely cause for concern about whether these expanding craft breweries will lose some of their hipster street cred.”

Keeping the Lagunitas brand—and its culture—intact is Magee’s primary challenge. He recalls that, as a home brewer in Northern California 20 years ago, he was inspired by Mendocino Brewing Company, a nearby operation whose brand conjured “weed growers, survivalists, and communes.”

Magee, who would rather talk about Hunter S. Thompson and Frank Zappa than the merits of various varieties of hops, has cultivated Lagunitas’s image in a similar, quintessentially Northern California fashion: fun, creative, unorthodox, relaxed, and proudly independent. “I often say we’re not in the beer business, and it gets my conventional thinkers uncomfortable. We’re in the tribe-forming business, trying to knit people together. If we’re able to embed these things as core values, then long after I’m dead and gone, this is going to be an interesting place.”

James Schrager, a professor of entrepreneurship and strategy at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, has studied maverick corporate chieftains such as Ray Kroc of McDonald’s and Herb Kelleher of Southwest Airlines: “When a company has a charismatic, iconic founder, then as long as that person is around, everybody gets the message. When they leave—that’s the issue.” (Magee says he has no plans to go anywhere.)

Indeed, in Petaluma, where Magee is roaming from building to building in baggy jeans and an untucked short-sleeved button-down, there’s little evidence that Lagunitas is going corporate anytime soon. A backpack-size Portuguese podengo jumps onto the office reception desk to greet visitors, and half a dozen dogs nap on beds adjacent to their owners’ cubicles.

Out back, where some brand-new brewing equipment is mostly up and running—the same gleaming system that has been ordered for Chicago from a Bavarian manufacturer—Magee jokes with a guy working a new vacuum-powered keg mover. “You’re going to get fat now, but at least you don’t have to worry about dropping a keg on your toes,” he says. The worker nods and replies solemnly, “I’ve got great toes.”

A Magee-led tour of the Lagunitas complex is an idiosyncratic event. Mine includes landmarks such as the amphitheater for musical performances that he dug himself and the brewing equipment that was ruined in transit (by a hurricane, no less) from Germany and now is a pile of scrap metal in the parking lot. I trail him as he searches the various offices and corner spaces for an acoustic guitar; once one is located, we trade versions of a riff by Mississippi bluesman R. L. Burnside. Then comes the offer to smoke weed. When I decline, he asks, “How can you be creative without it?” We settle for three beers apiece and his favorite veggie panini from the company brewpub.

As he meanders, it becomes very clear that Lagunitas will maintain its unique character as long as Magee is taking orders only from his slightly offbeat inner drummer.

Magee makes a special effort to dispel any notion that he’s a hard-charging corporate executive. “I haven’t reimagined myself as a titan or a baron. I’m still a bum,” he says. “I Googled myself for half an hour this morning, then got high and jumped in the shower. I played with my dog, then came to work.”

That’s not a typical CEO admission, but it’s hardly off message. For one thing, marijuana is absolutely fundamental both to the company’s self-image and to the rebellious, relaxed ethos it tries to convey to its customers. Two of its beers are winking tributes to marijuana use: The Waldos’ Special Ale is named for a famed group of Northern California stoners; Undercover Investigation Shut-Down Ale commemorates the 21-day suspension given the company by California’s Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control in 2005. That year, regulators set up a sting operation on Lagunitas’s property after hearing about monthly parties where pot smoking was de rigeur. No one was arrested in the sting because no drugs were sold. After that, Lagunitas began asking its employees to light up offsite. (The company has since posted signs on its campus that say “No Pot Smoking Anymore,” but the brewpub opens five days a week at 4:20, a sly reference to the time the Waldos met for their afternoon smoke break.)

And while California and Illinois have very different statutes on the books for dealing with marijuana consumption, Magee has some fortunate timing: In June 2012, Chicago decriminalized possession of less than 15 grams of marijuana (or about 25 joints). And on August 1, a bill legalizing medical marijuana in Illinois was signed into law by Governor Pat Quinn. (Lagunitas says the timing of its move was coincidental.) The company’s run-in with the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control doesn’t trouble the 28th Ward alderman, Jason Ervin. Lagunitas’s arrival is “a great feat for us,” he says, stressing that Chicago did not sweeten the deal with any tax incentives.

The one person to express any trepidation did so only jokingly. When I asked Josh Deth, CEO of Chicago’s Revolution Brewing and a member of the board of directors of the Illinois Craft Brewers Guild, about Lagunitas’s herbalist reputation—in this case, I was referring to the company’s growth and whether it might contribute to a nationwide hops shortage—he stopped me cold. “Forget hops,” Deth said. “Some people here are very worried about the marijuana supply once Lagunitas arrives.”

The bold acknowledgment of a freewheeling culture isn’t just the byproduct of a hemp-loving founder; it’s key to the company’s offbeat, independent reputation—one Magee believes is crucial to keep in the Chicago outpost. But he can’t very well advocate the use of illegal drugs in his company’s employee handbook, so what’s the alternative?

“If you can answer that question, you should come work for Lagunitas,” says Brandon Greenwood, the company’s vice president of operations in Chicago and a former executive with Mark Anthony Brewing, the Chicago-based group behind Mike’s Hard Lemonade. “There is that part of the culture; I don’t know how it’s going to translate into the Chicago world.”

To bridge other aspects of the Midwest-West divide, Magee has already begun shuttling employees between the two sites. (The Chicago brewing facility and adjacent 250-seat pub will employ 50 to 60 people when fully operational.) Mary Bauer, a former Anheuser-Busch brewer whom Lagunitas recruited from Pepsi to be head brewer in Chicago, will spend a month in Petaluma, as will other Chicago hires. Meanwhile, Magee is leasing one condo in Bucktown for himself—he’s been commuting back and forth at least twice a month—and a second in Uptown for Lagunitas guests from California. Marshall, the head brewer in Petaluma, visited Chicago in June to meet local brewers and sample their wares, and he left crowing about the Lincoln Square brewery Half Acre as well as the Bucktown brewpub and pizzeria Piece.

Magee has also enlisted his relatives to anchor the Chicago operation. He and his wife don’t have kids, but they have deep Midwestern roots. Magee’s sister, Karen Hamilton, has worked for Lagunitas from Chicago since 2005, and two of her sons, who are in their 20s, work for the company too. “We don’t have as many beards and long hair, but we seem to attract the same people everywhere—people who want to be part of a family, not just an employee,” she says.

There are two sides to Tony Magee: the relaxed, convivial brewer who likes a good time and the pugnacious gadfly who isn’t afraid to pick a fight. Three hundred executives from the largest breweries and distributors across the country saw the latter when they gathered in San Antonio for the two-day Beer Industry Summit in January.

On the second day, Andy Goeler, the CEO at Chicago-based Goose Island Beer Co., was scheduled to speak. Goeler is a 30-year Anheuser-Busch veteran with a New Jersey accent and a graduate degree in marketing, and his presentation included a short video that showed some Goose Island brewers at work.

Goeler left briefly as the video played, and Magee, seeing an opportunity to make a statement, blocked him from returning through the conference room door. Goeler pushed and pushed, but Magee countered from the other side. Once the Lagunitas founder believed he’d made the Anheuser-Busch executive nervous, he relented.

This is how Magee chose to introduce himself.

The two men shook hands—Goeler, the consummate marketer, and Magee, the disrupter, impassive except for an odd little grin. Magee remembers saying as their hands pumped up and down, “It’s good to meet you, because I only allow myself to dislike people that I’ve met.”

The source of Magee’s ire? Rumors that Goeler had trash-talked his Petaluma-based competitor during an Anheuser-Busch InBev convention in Chicago the previous year. Magee says he heard from a Goose Island employee that Goeler vowed to block the success of Lagunitas’s Chicago expansion. (For his part, Goeler says that he doesn’t remember the specifics. “I try to jazz everybody up—‘Let’s go out and sell!’ ” he says. “I don’t remember issuing that challenge particularly, but probably so.”)

Mostly, though, Magee just hates Big Beer. Get him on the subject and prepare for a freewheeling monologue: “I often think of that scene in Star Wars: the light saber argument between Darth Vader and Obi-Wan Kenobi. Darth kind of gets a swing at him, and Obi-Wan goes, ‘If you strike me down now, I’ll become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.’ I mean, that’s the place where craft is right now—the big guys don’t even know where to start with it. They approach it as market share. But if you’re Tom Petty, and you sold incrementally more albums than anyone else in a given year, would you do a press release? No, you’d just feel real good that your career is still alive and people understand what you’re trying to say.”

In this rambling analogy, Magee is both Obi-Wan Kenobi, the defender, and Tom Petty, someone he views as an artist with ideals. Translation: Whether the world needs him to or not, Magee has become the self-appointed guardian of craft brewing’s soul.

After meeting Goeler in San Antonio, he took to Twitter to announce that he would “rather put out my eyes” than sell to Anheuser-Busch InBev, as Goose Island founder John Hall ultimately did in 2011 (for $38.8 million). That company, however, had not been counted by the Brewers Association as a craft brewery since 2006, the year Hall surrendered a stake of more than 25 percent in the company to the Portland, Oregon–based Craft Brew Alliance, whose brands include Redhook Ale Brewery and Widmer Brothers Brewing.

Magee says he’s been approached about selling Lagunitas, but he can’t stomach the thought of someone else in charge of a company that bears so much of his personality. Having spent most of his 20s searching for his identity—a search that involved getting high, composing ad jingles, driving cabs, selling luggage, and working as a night watchman in a bowling alley—Magee the man is inextricably intertwined with the Lagunitas ethos. “The brewery would be like my avatar, and what it did would always reflect on me,” he gripes. “It would be like, ‘Oh my God, it’s making a raspberry IPA!’ ”

So while Goeler speaks excitedly about staying ahead of the next trends in the craft segment, a conversation with Magee starts with a discussion about using brewing as a canvas for creative self-expression. To him, market research is a 21st-century plague. “If you’re an accountant, you’re comparing yourself to someone else’s Q1, or this book that was written about in the Harvard Business Review, or this or that,” he says dismissively. “But when I studied composition in school, I listened to Frank Zappa. I listened to Beethoven. You’re comparing yourself to the best of anything that ever was.”

He acknowledges that his challenge is to convince craft beer drinkers that even if Lagunitas becomes a bigger player, it’s still a full-fledged member of the craft community alongside midsize breweries like Half Acre or the scrappy upstarts such as Ale Syndicate or Wicker Park’s Pipeworks Brewing Company (see “The Best Beer in Chicago”).

“The question is whether you lose authenticity in your brand just because you get big,” says Ray Daniels, a Chicago-based author of several books on beer, including Designing Great Beers, and the founder of a certification program for cicerones, the beer world’s version of sommeliers. (Daniels married Magee’s sister in May and is an investor in Revolution.)

Daniels says the answer is to demonstrate that there’s a singular and genuine personality behind the beverage, rather than a faceless committee. To start winning over Chicagoans, Magee has been careful in choosing the events and musicians he aligns his company with. At the 2012 Hideout Block Party, headlined by Iron and Wine and Wilco, Lagunitas was the biggest beer company represented, with a trailer of its IPAs on tap. As the afternoon wore on, the line of indie-music lovers cloaked in vintage dresses and sleeve tattoos grew ever longer, but few uttered any complaints.

Face time is also part of Magee’s strategy for maintaining credibility with small brewers. In July 2012, he met with members of the Illinois Craft Brewers Guild to explain why Lagunitas is coming to Chicago, and he promised not to hire away their employees. He has visited homebrew supply shops in Chicago, and during his blues-guitar gig in Roscoe Village, he bought beer for most of the crowd—not just Lagunitas but suds from Chicago’s tiny Lake Effect Brewing Company as well. He’s also considering advising and investing in a series of small breweries, a project similar to the accelerator programs popular in the world of Internet startups.

That aspect of Magee’s personality is somewhat at odds with his penchant for taking shots at the big guys. He has feuded not only with Anheuser-Busch InBev but also with executives at New Belgium and Sierra Nevada. The North Carolina breweries that are being built for those brands were each facilitated in part by millions of dollars in tax incentives—a setup that Magee has publicly criticized. Last August, he took to Twitter to complain in a series of posts:

“This is your tax money being diverted to a wealthy company. We are becoming the people we set out NOT to be. No incentives for us in IL. Important to say I’m not chiding the brewers or the beer of NBB or SNB or anyone else whose employer takes tax monies as payola . . . but those companies hold their personal values up as their marketing flags. Those values include this.”

Last fall, Magee vowed to stop tweeting, acknowledging his knack for stirring up controversy. Yet he was back in January, first announcing to his Twitter followers his “kinder-gentler version” of the account and then, two weeks later, firing yet another shot across his Chicago bow in the direction of Goose Island. “I said I’d not poach from local breweries to staff Chicago, but I think we could make an exception for Goose folks . . .”

“Call it ‘sanctuary.’ ”

Magee chose to return to the Chicago region mostly because it is his hometown. He attended high school in Buffalo Grove, played for the marching band at Six Flags Great America, and slept on his mom’s couch in the suburbs during his 20s while he figured out his life.

But Chicago is also a transportation hub and a key market for his product, and Lagunitas’s new urban address lends its expansion a different flavor from that of Sierra Nevada or New Belgium. In addition, the brewery’s North Lawndale location will help revitalize a downtrodden manufacturing district largely devoid of shops and restaurants, says Ervin, the alderman, who hopes Lagunitas’s presence will create jobs in his ward and draw taproom patrons and brewery tourists to the site. “The jobs, the tasting room—all of that is going to work well for the community,” the alderman says.

The site, formerly the Ryerson steel fabrication plant—at 1843 South Washtenaw Avenue—sits at a peculiar crossroads between the neighborhoods of North Lawndale, which ranked fifth among Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods for violent crime from June 2012 to July 2013, and the Near West Side, which ranked 24th. Two blocks to the west of the complex is Douglas Park, and in this direction Lagunitas adjoins a street lined with single-family homes. To the east, though, lies a massive vacant rail yard, an oasis of weeds and concrete with a stunning view of the skyline.

After the steel fabrication plant closed in 2011, the hulking white metal frame was bought by a film production company, Cinespace Chicago Film Studios, which is now Magee’s landlord. Cinespace is still filming in several buildings in the complex (the space that houses Lagunitas is too close to the train tracks and, thus, too loud); when the actors and crew from the shows that are filmed onsite—think the TV shows Chicago Fire and Chicago P.D. and the movies Divergent and Transformers 4—take a break, they’ll soon have a brewpub next door where they can drop in for happy hour.

In the Lagunitas space, new semitruck bays have been cut into the southwest corner of the building, and eight giant malt storage silos occupy the spacious parking lot on the southwest side. This summer, the brewery started receiving its state-of-the-art 250-barrel Rolec brew house system, which is made in Chieming, Bavaria, just north of the Austrian border. The system—identical to the one in Petaluma—consists of a mash mixer, lauter tun, wort receiver, wort kettle, and whirlpool and can produce up to 600,000 barrels a year. The company hopes to soon invest in a second brew house, which would bring it up to the goal of 1.7 million barrels annually. Already, there are 12 fermenters, a number that will likely increase to 40 during 2014.

Lagunitas’s costs to open the production facility were initially estimated at $15 million, but that number was revised over the summer to $22 million to reflect a late-in-the-game call by Magee to aim for a greater production volume than he had initially intended. “All these decisions got made on the back of a galloping horse,” he says.

The plan is to brew Magee’s own signature IPA, plus other year-round and seasonal brews. The Chicago outfit won’t make the funky small-batch beers served in the Petaluma brewpub, such as the quirky, tart Freaky Kriek; instead, those beers will be shipped in from California. These rare releases will no doubt be a draw to a public whose thirst for fly-in-your-face beers can seemingly never be quenched.

But there is no getting around the fact that the taproom—which will be trimmed with redwood to evoke laid-back Northern California—is located in an area with high crime, unemployment, and foreclosure rates and little in the way of a Petaluma vibe. To help lure patrons, the taproom will offer food and live music nightly, mostly singer-songwriters and Americana acts. Beer geeks can get a particular thrill surveying the 24/7 brewing operation through its glass enclosure.

In Petaluma, Lagunitas closes its taproom at 9 p.m. in order to avoid competing with local bars that sell the company’s beer. That won’t happen in Chicago, in part because the South Western Avenue corridor is starved for retail businesses. There’s just one bar within walking distance: a blues bar called the Water Hole at 14th and Western. It bills itself as “Chicago’s Lil Juke Joint,” and often enough, the smell of barbecue wafts in from a barrel smoker outside.

Until Magee sauntered into the tiny spot this summer, handed the owner a dozen posters, and preached his gospel of craft beer, the only two beers on tap had been Miller Lite and Miller Genuine Draft. Now the Water Hole is carrying bottles of the “homicidally hoppy” India pale ale that Magee started brewing in the 1990s, and a neon Lagunitas sign flashes from a window facing Western Avenue.

There goes the neighborhood.