Matthew Baron plops his long, lean frame onto a couch at Narwhal Studios in Wicker Park and starts talking about death. “There’s this prayer I often think about, the St. Francis Prayer, that’s used a lot in AA,” says Baron, who has been sober since 2007. “There’s a line in it that goes, ‘It is in dying that we are born to eternal life.’ ”

It’s June, and Baron is at the studio recording an album with his indie rock band, Young Man in a Hurry. He’s managed to sneak away for a few hours from the West Loop apartment he shares with his wife, Whitney, and their 2-month-old child, Jarvis. The band is a side gig. Baron, 40, is a Chicago Public Schools teacher and the frontman of Future Hits, a children’s educational rock group. He has kind eyes, a tuft of curly brown hair, and a laid-back, accepting mien that may explain why kids are drawn to him, whether he’s in a classroom giving instruction or at a library playing guitar and singing songs about eating healthy foods.

But three years ago, the contented life he had built suddenly fell to pieces. “I’ve witnessed what it is like to die,” he continues. “In a way, the old me did die. I lost all my plans. I lost my great reputation.”

The telephone call that upended everything came late on Friday, May 3, 2019. Baron was in a hotel room in New York City, where he was scheduled to play a series of concerts with Future Hits. On the other end of the line was the familiar voice of Deborah Clark, then the longtime principal of Skinner West Elementary, the high-achieving West Loop school where Baron had taught social-emotional learning and English as a second language since 2015. Clark told him she needed to discuss a serious matter.

At first, Baron wondered if she was calling about his recent request for a yearlong sabbatical. Just two weeks before, he had sat across from Clark and nervously asked permission to join his then fiancée, Whitney, while she studied for a master’s degree in Norway. That day in her office, Clark told Baron that Skinner’s “superstars,” as she often called the students, would sorely miss his joyful presence.

Today, these students’ parents speak of Baron as more of a friend than a teacher, someone they would invite to perform at their children’s birthday parties. His Skinner colleagues share stories of how he would gladly give up his lunch break to lend an ear to a student going through a tough time and would hand out food to kids in need.

Clark felt Baron had earned the time off. She smiled, hugged him, and said, “You’ve got to follow love, Mr. Baron.”

But now, over the phone, Baron noticed a quiver of concern in his boss’s voice.

“Mr. Baron, something you wouldn’t believe is happening here at Skinner,” he recalls Clark telling him, “and it involves you.”

At that moment, Baron says, his stomach dropped, “like I was at the top of a roller coaster.” He reflexively bit at a fingernail.

“Wow, Mrs. Clark, I’m really sorry to hear that,” he said. “What’s happening?”

“There’s this sixth-grade student … well, Mr. Baron, he’s saying that you touched him.”

“What?”

Baron’s breathing grew quick and shallow. His eyes fixated on the hotel room’s heavy golden drapes as Clark laid out the details of the allegation.

A 12-year-old boy, M. (Chicago is using initials to protect the identities of minors), had come forward three days before, saying that when Baron was substituting for the student’s regular reading teacher some months earlier, he rolled his chair up to M.’s desk and put his leg and elbow next to the boy’s, so that they touched. Then, M. said, as a CNN video played in the darkened classroom, Baron massaged the boy’s neck before putting his hand beneath the boy’s shirt and rubbing his back for about nine minutes.

Clark informed Baron that the Chicago police and an Illinois Department of Children and Family Services investigator had been to Skinner. She also told him that, with the allegation under investigation, he would not be allowed to report to school until further notice.

A lump grew in Baron’s throat.

“Mrs. Clark, this is unbelievable,” he said. “This did not happen.”

When the call ended, Baron was bewildered. Reality suddenly seemed misshapen, as if the world had been jarred from its axis, flinging him into some kind of twilight zone.

“That’s the paradox of all this,” Baron says. “I have always been the biggest advocate of kids having a voice. But what happens when that voice is not speaking the truth?”

In a panic, he searched his mind for any interaction he may have had with M. or any other student that seemed out of the ordinary. Then, like one of those disorienting zoom shots in a Hitchcock film, it came into vertiginous focus: While subbing for a sixth-grade class on April 29, the day before he left for New York, he disciplined a girl named A., who he knew was M.’s friend. She’d been talking in class, and Baron had asked her multiple times to keep her voice at a reasonable level. A. didn’t listen, so he told her to sit at a table near his desk. She refused, saying Baron made her feel uncomfortable. She said she would rather go to the school office than sit by him. Baron allowed her to go, and he emailed the principal and some of A.’s other teachers to let them know she was being insubordinate.

He recalled one final detail from that day: After school let out and he exited the building, Baron says, he saw A., M., and a couple of other students huddled together. He waved and said good night but received a chilly nonresponse. The accusation from M. was brought to school officials the next day.

In that moment, Baron realized what he thinks happened: “They were retaliating.”

Eleven months before the allegation, in June 2018, the Chicago Tribune published a bombshell investigative series called “Betrayed.” It revealed that Chicago Public Schools was failing to protect students from sexual abuse and assault by teachers and other school personnel. In a close examination of more than 100 cases over the preceding decade, the Tribune found repeated instances of CPS officials improperly responding to allegations brought by students. Some claims simply went unreported, a violation of the legal requirement that school officials tell authorities about suspected child abuse. In other instances, school employees took it upon themselves to play detective, questioning the student, their parents, and even the alleged abuser before bringing the claim to the proper authorities, undermining the integrity of any subsequent investigation.

In the wake of “Betrayed,” which landed amid a broader cultural push to more seriously heed allegations of abuse and harassment, CPS vowed to review and reform its handling of such cases. Among the most notable changes was the expanded role given to the CPS inspector general’s office, the school system’s independent watchdog, in probing reports of sexual abuse and misconduct. Previously, CPS’s legal department had investigated claims while simultaneously defending the system against lawsuits brought by the alleged victims — a glaring conflict of interest. CPS also initiated a policy of immediately removing from school any employee accused of sexual abuse, pending the outcome of an investigation, rather than waiting to determine if credible evidence existed.

It was an understandable reaction to a situation that had become intolerable. But it also meant that wrongfully accused teachers would inevitably have to fight a presumption of guilt that could permanently stain their reputations.

In Baron’s case, he was immediately suspended, although he continued to receive his salary. He was labeled a pedophile on neighborhood social media forums. He was named on television newscasts. He was interrogated by the police and locked in jail. He was slapped with a battery charge and prosecuted in criminal court.

All told, it cost him about $27,000 in legal fees, nearly three years away from the classroom, and, not least, the standing that he had built over a decade as an educator and entertainer of children.

“Before this happened, I was the kind of person who thought if somebody makes an allegation, it must be true. Why would they make it up if it didn’t happen? I would see a headline like ‘Teacher Accused,’ and I’d be like, ‘That guy’s a creep,’ ” Baron says. “It’s so ironic, because as a social-emotional learning teacher and just who I am as a person, my job has been to work with students to help them feel comfortable in their own skin and advocate for themselves and have agency.” As a roving “resource teacher,” he helped selected students throughout the school develop “soft skills,” such as managing emotions, practicing empathy, and making responsible decisions.

“That’s the paradox of all this. I have always been the biggest advocate of kids having a voice. But what happens when that voice is not speaking the truth?”

A knock at the door at 6:50 a.m. jolted Baron out of a deep sleep. It was May 8, 2019. In the five days that followed his conversation with Clark, Baron had grown paranoid. Calls from unknown numbers spooked him. He holed up in his garden apartment, just a block and a half from Skinner. The rare times he ventured out, he wondered if the neighbors he passed on the sidewalk were looking sideways at him, somehow aware of the as-yet-unpublicized accusation hanging over his head.

Baron’s heart raced as he shuffled, half-awake, to answer the door, whose small window revealed two serious-looking men in plain clothes. They introduced themselves as Chicago police officers and told him he would need to come with them to the station but did not explain why. Baron assumed it was to clear up what he saw as confusion surrounding the allegation. He threw on jeans, a sweater, and sneakers. Not knowing where exactly they would be taking him or how long he would be gone, Baron asked if he should bring a bottle of water and a book. The officers stifled laughter. “You won’t need any of that where you’re going,” he recalls one of them saying. They led him to an unmarked SUV. According to a lawsuit Baron later filed, he wasn’t told he was under arrest, wasn’t read his Miranda rights, and wasn’t handcuffed, because, as one of the officers explained, “You seem like a nice enough guy.” In the back seat, Baron began texting a lawyer friend.

At the 11th District police station, at Harrison Street and Kedzie Avenue, the officers led Baron to an interrogation room. An hour passed before David Watson, a detective with a clean-shaven head, entered the room and began asking questions.

Baron says he told the detective he’d rather wait to answer questions until he had a lawyer present. “I’m just here to get to know you and see what kind of guy you are,” Baron recalls Watson saying. The detective asked him some basic questions, about his age and teaching career, which he answered. But Baron also remembers being needled by Watson. After Baron confirmed he had been divorced and was newly engaged, Watson asked the age of his fiancée.

“Thirty-two, sir,” said Baron, who was then 37.

“Oh,” he recalls Watson saying with a smile. “You like younger girls, huh?”

“Officer, I don’t mean any disrespect,” Baron says he replied. “I just don’t want to answer any more of your questions.”

Soon Baron got his fingerprints and mug shot taken and was on his way to lockup. Still, he says, no one ever explicitly told him he was under arrest: “That’s how naive I was.” When he asked to use the restroom, Baron says, the cop ushering him around replied, “You never been to jail before? There’s a toilet in your cell.” Behind iron bars, Baron eyed a filthy toilet bowl and a couple of metal-slab bunks jutting from a wall. As the cop closed the cell door, Baron recalls, he said, “Welcome to paradise.”

“It felt like I was spiraling into a nightmare,” Baron says. Sitting in the cell, he remembered that after he founded the West Side art space Silent Funny, he began attending Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy, or CAPS, meetings — part of the city’s community policing effort — and some of the officers he had come to know had worked out of the 11th District. “And here I was,” he says, “locked in their jail.”

As the hours dripped by, morning into afternoon, more people were brought into the lockup. From what Baron could tell, most were being held on drug-related charges. Guys yelled between cells, talking about how they got picked up, sharing intel on dope spots. At one point, Baron says, he saw a cellmate snort something off his hand.

Eventually, Baron was able to meet with George Grzeca, the veteran criminal defense attorney his lawyer friend had recommended. When Grzeca had finally reached Watson, the detective said Baron could be facing a felony charge, depending on the decision of the state’s attorney.

A fellow inmate barked at an officer for the time. Almost 4 p.m. The previous day, Baron had seen the email Skinner’s principal had sent out summoning the school’s faculty to a meeting at 4 p.m. the next day. He knew it was there she would inform them that a staff member had been removed due to an allegation of inappropriate contact with a student. He grew embarrassed as he pictured his coworkers talking about how he was the one under investigation.

“The realization of the severity of the situation piled on me moment to moment,” he says. “It was a carriage rolling down a hill, and I couldn’t dash over to stop it from falling.” He brought his focus to the rhythm of his breathing, and he began to feel a little better.

“I was getting swallowed by this nightmare, But then I would have these washes of complete and utter peace. In my heart, I knew the truth.”

The ability to find serenity amid chaos was something Baron had learned in recovery programs during his dozen years of sobriety. Later his mother would tell him, “If there was one person who I knew could survive that experience in jail, it was you.”

The son of a cosmetics executive mother and jazz musician father, Baron grew up in Skokie and Vernon Hills. Through high school and college, he was interested in two things: playing music and partying. He didn’t think much about his future. But as he moved into his mid-20s, Baron began to notice that his friends were settling down, taking their work more seriously. “And I was one of the only guys,” he says, “who still wanted to just party it up.”

One night when he was 23, after drinking heavily at the now-defunct Rockit Bar & Grill in River North, he was denied entry to a neighboring bar because it was clear, as Baron puts it, “I was out-of-my-mind drunk.” Instead of going home to sleep it off, he called 911 to report the bar. When the police arrived, an officer handcuffed Baron and put him in the back of the cruiser. Then, as they were headed to the station, a call came over the radio, and the car suddenly whipped into the parking lot in front of an Al’s Beef. The officers, Baron recalls, had to respond to an incident in progress. One uncuffed Baron and told him to go home. “That was what brought me to my senses,” he says, “that if I didn’t stop drinking, something bad would happen.” On top of that, a friend had recently died in a car crash while riding with a drunken driver, and another had fatally overdosed on prescription pills. Baron felt he had been given what is known in recovery parlance as “the gift of desperation,” a willingness to allow help into his life. He began attending recovery meetings, and he would eventually become a sponsor himself, helping others with their sobriety.

Around the same time, Baron found himself in search of a new career path. He had worked an uninspiring job in logistics sales after graduating from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He met with a life coach, who helped him examine his interests for potential new job fields. He had been a camp counselor and always enjoyed working with kids and felt they responded to him. He spoke Spanish fluently. He wanted to be a musician but wasn’t willing to be a starving artist, so he sought a job that would allow him time off to pursue his passion. He soon decided he wanted to teach ESL. In 2009, he enrolled in a two-year master’s program in education through Quincy University in downstate Illinois. A few part-time jobs at CPS schools in Edison Park, Lake View, and the Near West Side led to a full-time position at Skinner during the 2015–16 school year.

All the while, he was deeply entrenched in a 12-step recovery program, and he adopted a philosophy of release that brought him a sense of peace and sanity. “I learned that I’m not in charge of my life,” he says. “I learned to trust a higher power.” He also began developing a meditation practice, including 10-day silent retreats where he learned the same focused-breathing technique that the Buddha himself is said to have used to attain enlightenment.

“That is the mindset that I took into the jail cell,” Baron says. “I was getting swallowed by this nightmare, but then I would have these washes of complete and utter peace. In my heart, I knew the truth.”

After tossing and turning all night on a prison-issue gym mat, he was finally released on a personal recognizance bond and informed of his fate: A Cook County assistant state’s attorney had rejected felony charges; however, M.’s mother had decided to pursue a misdemeanor battery charge, which did not require approval of the state’s attorney’s office. The charge, he was told, carried a maximum sentence of one year in prison.

Beyond the walls of Baron’s jail cell, word had already begun to circulate through the Skinner community that a teacher had been removed due to an abuse allegation. And it didn’t take long for elementary school parents to do as elementary school parents are wont to do when neighborhood news breaks: dissect it and snipe at each other about it on Facebook.

“It’s time to SPEAK UP,” M.’s mother wrote on the True West Loop page, which has nearly 17,000 members, sharing the letter Clark had sent informing parents of the allegation. “This letter forgot to mention that you can call 911 to report your case. Also, please feel free to reach out to me directly.” In a follow-up comment, she added: “Ask your kids if something happened to them.”

“Who is the staff member?” one member of the group asked.

“Mr. Baron who teaches SEL (Social Emotional Learning),” M.’s mother replied.

“This is already SO wrong, but the fact that he f——ing teaches social emotional learning just takes it to a whole new level of wrong,” someone else wrote. “It’s like he’s been studying how to manipulate the vulnerable. F——ing coward.”

Another person took issue with M.’s mother naming Baron: “Before putting this out here on Facebook, there are a few things to consider. Firstly, the school has not yet released the teacher’s name. I would like to remind us all that one is innocent until proven guilty.”

“If this would happen to your son you would not be thinking this way,” M.’s mother shot back. “This teacher is a pedophile.”

“I get it — as a mother, she was angry,” recalls Fadi Matalka, who had a child enrolled at Skinner at the time. “But I was like, Oh my God, she just tarnished this person’s reputation.”

Soon M.’s mother began contacting parents directly to ask if their children had similar stories about Baron. “When we told her [our son] was very adamant that nothing happened, she didn’t give up,” says Justin Kaufmann. “It was like, ‘Are you sure?’ It seemed like a fishing expedition.” (M.’s mother initially agreed to an interview for this story but later declined after discussing it, she says, with M.’s father, her ex-husband.)

Parents and teachers say M. had been the occasional target of name-calling over the years, and his mom would often come passionately to his defense. “She was very protective of her son, and she went to bat for him immediately. This was standard procedure for her,” says a parent close to M.’s mother who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “But this incident was, of course, elevated, much more serious than any kind of teasing.”

“It felt like everyone was grieving, as if there had been some traumatic accident at school and we had to just keep going with our happy little smiles and rainbows and unicorns in the classroom,” first-grade teacher Kara Martin says of Baron’s removal.

Days before the allegation went public, teachers knew something was afoot. “I saw some people taking kids down to an empty room,” recalls Jeff Merkin, a second-grade teacher, “and I asked someone, ‘What’s going on?’ And they were like, ‘Oh, that’s DCFS. They’re interviewing kids. Something happened in the building.’ And then I heard, later that day, Matt’s name being thrown around about inappropriately touching a child. I was shocked — shocked. Everybody was just like, ‘There’s no way this is true.’ ”

A couple of days later, on May 8, Clark faced the school’s staff with tears in her eyes. “This,” several teachers remember her saying, “could be any one of you.”

“It was so hard, so gut wrenching,” recalls Clark, who recently retired after 28 years at Skinner. “It’s all protocol. No judgments. You just report as it’s reported to you and follow the guidelines of CPS. And that was the sad part — you couldn’t bring your own feelings into it, except to hope that everything would turn out well for the teacher.”

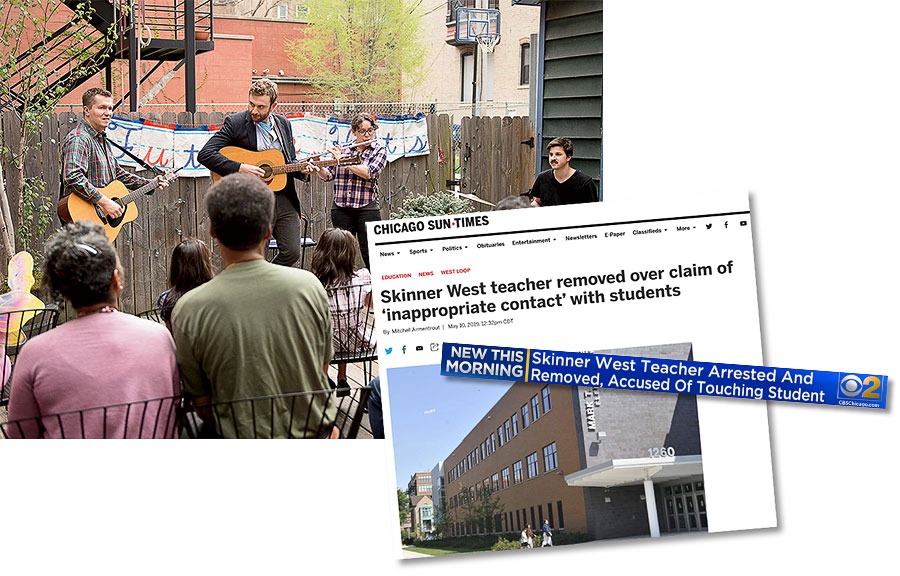

It wasn’t long before Baron’s name cropped up alongside headlines like the one blaring from a CBS Chicago chyron: “Skinner West Teacher Arrested and Removed, Accused of Touching Student.” M.’s mother spoke to WGN, which reported that “she fears the teacher has been grooming her son the entire school year.”

“They were painting this picture of him as being this monster,” says Merkin. “And I was like, ‘Listen, I know this guy, and this picture you’re painting isn’t even close to the person he is.’ ”

In the wake of Baron’s removal, a chill pervaded the halls of Skinner. “It felt like everyone was grieving, as if there had been some traumatic accident at school and we had to just keep going with our happy little smiles and rainbows and unicorns in the classroom,” says Kara Martin, a first-grade teacher.

Shortly after he was served with an order of protection, barring him from any contact with M. and his parents, Baron felt compelled to abandon his West Loop apartment and sought refuge at his parents’ home in Vernon Hills. As a condition of his bond, he was not allowed to leave the state without the court’s permission. And so, two days before he was scheduled to play a Future Hits concert in New York, he was forced to cancel the show.

During this time, Baron devoured articles on public shaming and false allegations, particularly those that tried to explain why someone would make an untrue claim. Sometimes the accuser wants to intentionally hurt the accused; other times the accuser may have a mental illness. He read the book Conflict Is Not Abuse, in which author Sarah Schulman argues that inflated accusations of harm can be used to avoid accountability. He watched The Hunt, a 2012 Danish dramatic film about a kindergarten teacher falsely accused of abusing a student.

Baron also began attending daily Al-Anon meetings — traditionally for the families and friends of alcoholics — to help find a sense of peace. For that hour, he would turn off his phone. “I’d say, I’m not going to talk to my lawyer. I’m not going to try to fix anything. I was just focusing on my serenity.” He also turned to meditation and swimming and began seeing a life coach. “It was all about getting very quiet internally, because the external gaslighting was so powerful.”

In November 2019, Baron had his day in court: a bench trial at a brown brick courthouse in Homan Square. Cook County circuit judge Robert Kuzas presided, and Baron was pleased to see Skinner teachers and parents seated in the gallery to show their support.

Assistant State’s Attorney Arthur Haynes called M. and A. to the stand in succession. Both students testified that Baron touched M. in a darkened classroom while a brief CNN video played. But Baron’s defense attorneys, Grzeca and Jeffrey Moskowitz, zeroed in on inconsistencies. For instance, the friends could not agree on which parts of M.’s body were allegedly touched: M. testified it was his neck and back; A. mentioned M.’s thigh. They differed on the length of time of the alleged contact: M. said nine minutes; A. said a minute or two. There were also discrepancies with the date of the alleged incident: In his original statement, M. said it happened in March 2019, but he testified in court that it occurred in January.

And then there was the issue with the lights. Both M. and A. testified that Baron cut or dimmed the classroom lights during the video. That’s when Grzeca called to the stand Yamini Irvin, a teacher Baron subbed for regularly during the 2018–19 school year — including in January, when the incident was alleged to have happened. She testified that due to an electrical fluke following construction on Skinner’s annex, the lights in her classroom were always on throughout that time period. “We could not turn them off. We could not adjust the strength,” she said in court. “And that continued into September [2019].”

Finally, after Baron testified on his own behalf, he was cross-examined. “Do you ever sit close to your students to talk to them?” asked the assistant state’s attorney.

“As a teacher, we have to sit near students,” Baron said.

“As a teacher, do you have to put your hand in a student’s shirt?”

“I would never do that.”

“As a teacher, do you ever have to stroke a student on the back of the neck?”

“I never did that.”

“As a teacher, do you ever have to touch a student’s thighs?”

“I would never do that, and I’ve never done that.”

In his closing argument, Grzeca contended that the scenario was implausible. “You have a classroom, lights full blown, 30-plus students sitting in there,” he said. Would a teacher really massage a student for nine minutes in full view of his class?

As they waited for Kuzas to make his ruling, the Skinner parents and teachers in the gallery held hands. Baron stood before the judge, his knees shaking. “There’s an issue with credibility here — that means that there’s reasonable doubt,” Kuzas concluded. “There will be a finding of not guilty.” The spectators from Skinner stood and cheered. “In the lobby of the courthouse, the feeling I had was better than any wedding or bar mitzvah or any other big event in my life,” Baron says. “It felt like I was reborn.”

Later that day, he returned to the apartment he had fled after the allegation and put on some buoyant rock by Alex G, one of his favorite musicians, then went for a liberated run through his West Loop neighborhood. “I felt so happy,” he says. “I hadn’t been able to do that comfortably since it all began.”

In the afterglow of the verdict, Baron and his supporters had new hope that he would soon return to Skinner. Five months earlier, the Department of Children and Family Services had sent Baron a letter that said: “After a thorough evaluation, DCFS has determined the report to be ‘unfounded.’ ” The Illinois State Board of Education would also eventually clear him, and Baron thought he’d be reinstated before the end of the school year. First he needed the CPS inspector general’s office — which was short-staffed and inundated with a backlog of cases — to wrap up its investigation. But it wouldn’t be until November 2020, a year and a half after the allegation, that the office conducted its first and only interview with Baron.

CPS inspector general Will Fletcher declined to discuss the specifics of Baron’s case. In a statement provided to Chicago, Fletcher said, “Several factors affect the duration of investigations including whether they are impacted by intervening criminal prosecutions and obstacles in evidence-gathering posed by the pandemic. The OIG is committed to conducting fair and thorough investigations in a timely manner that promote student safety and respect the rights of victims and subjects alike.”

Baron found the delay puzzling. He noted that the office would open inquiries into far more sprawling cases than his and close them within a matter of months. The investigation into allegations against 13 individuals at Marine Leadership Academy in Logan Square, for instance, began around the same time as the review of his case but was closed a full year earlier. Baron would check in frequently with his Chicago Teachers Union attorney, who would tell him to sit tight, Baron says, that his file was simply caught in the office’s “stack of papers.”

As he waited, Baron filed a lawsuit in October 2020 against the City of Chicago and the four police officers involved in his arrest and interrogation, claiming false arrest and malicious prosecution. The suit also named M.’s mother, claiming she defamed Baron on social media. (Several months earlier, M.’s mother dropped the order of protection case against Baron after his lawyer moved to depose her and M.’s father.) Among the more salacious details in the complaint was that M.’s mom and Detective Watson began a romantic relationship sometime after Baron’s arrest, undermining the possibility of an impartial investigation. In a written response to the complaint, Watson admitted he and M.’s mother started a relationship but denied it compromised his work. In March 2021, the city agreed to pay Baron $50,000 to drop the suit.

With his career and reputation still hanging in the balance, Baron tried to forge ahead with a sense of normalcy. He married Whitney, who had recently returned from Norway, in a backyard ceremony at his parents’ home. He started hosting what he called “Zoom field trips,” playing Future Hits music for classrooms of remote learners during the COVID pandemic. He recorded and released albums with both of his bands. He became a pickleball instructor. He got certified as a life coach, as a way, he says, to use what he had learned over the previous two years to support other people experiencing crises.

The goal had always been to return to Skinner, to walk through its doors with his head held high, to put a final chapter on the redemption story. On March 2 of this year, Baron finally had that chance. He shared tearful moments with the other teachers, some of whom were seeing him for the first time since his removal nearly three years earlier. He entered a classroom full of students, who exploded into a chant of “Not guilty!” But Baron didn’t speak to his colleagues collectively until a staff development day more than a month after his return. It was there that he at last addressed what the school’s new principal called “the elephant in the room.”

“I’m Matt Baron, everybody, and it’s so nice to see so many familiar faces and new faces at Skinner,” he said. “I just wanted to address some experiences I’ve had over the past few years. I got to experience what it was like to lose everything overnight. And it was a great life lesson. I just knew in my heart that one day the truth would come to light.”

But despite Baron’s vindication in court, not everyone shared his understanding of the truth. The report from the CPS inspector general’s office had arrived in mid-January. While it concluded that “the evidence was insufficient to substantiate that Baron engaged in sexual harassment or misconduct,” it offered a determination that he had “rubbed [M.’s] neck and shoulders on one occasion during class, in or around early 2019.” It acknowledged witness contradictions regarding the date and length of time of the alleged contact and the questions surrounding the classroom lights but explained that significant weight had been put on the “consistency” of M.’s account across various investigative interviews and during trial testimony.

In addition to taking statements from M. and A., investigators had talked to two female students who alleged that Baron winked at students, and one added that he “stared” at them. However, the office concluded that the evidence was insufficient to substantiate those allegations. The investigators also found an incident report from 2017 in which an eighth-grade student said that Baron approached her and her mother on a CTA platform and “either patted or gripped [the student’s] shoulder ‘in an aggressive manner,’ though he did not sound aggressive when he asked her how she was doing.” According to the report, the mother asked Baron, “Why are you touching my child?” and he then introduced himself as a teacher at Skinner. The report included Baron’s statement that he tapped the girl on the shoulder to get her attention.

“I never know who knows and who doesn’t know,” Baron says. “If I’m booking concerts for Future Hits and don’t hear back from a promoter, I’m always questioning: Did they Google me?”

The office’s finding that Baron had violated CPS guidelines regarding staff-student boundaries would not prevent him from being reinstated. Still, the report troubled him, and he didn’t want to accept it. In early April, Baron’s personal lawyer, Jordan Marsh, sent the office a 10-page rebuttal. “The report omits relevant facts, glosses over conflicting allegations, ignores exculpatory statements, and fails to address gaping holes in its own analysis,” Marsh wrote. A union lawyer advised Baron to “take it on the chin,” that in the end it would have no effect on his job. “I get it — if I had done something,” Baron says. “But I haven’t done anything. I don’t want any finding.”

On one of his first days back at Skinner, Baron was on recess supervision duty in the school’s gymnasium. In the echoing cacophony of children at play, he distinctly heard a student yell, “Child molester!” It was a small but stunning reminder that although he had come back to school, he could never truly return to the life he once knew.

None of the media outlets that reported the allegation followed up with stories on Baron’s acquittal in criminal court. His lawyer sent requests to those news organizations to remove the articles from their websites. WGN agreed; CBS appended an update. But enough of the initial coverage remains that anyone who searches Baron’s name online might get the impression that he is still under investigation for touching a student.

“I never know who knows and who doesn’t know,” he says. “If I’m booking concerts for Future Hits and don’t hear back from a promoter, I’m always questioning: Did they Google me? Do they not want to associate with me because of the allegation?”

On the couch of the Wicker Park recording studio, Baron admits he sometimes worries how the dark cloud that follows him will affect his future. Then he remembers: serenity. In the most anxious moments, he mentally transports himself back to the jail cell on the West Side. It’s his way of tapping into the inner peace he was able to cultivate as his life collapsed around him. “That was the moment when I realized, regardless of the outcome, I will be OK,” he says. “Because I know what’s true.”