Last year Chicagoist editor Chuck Sudo posted the above picture of a car elevator in the Loop—source unknown, apparently from 1936—and asked "Where Was This Car Elevator Located?" It made the rounds: Twitter, Reddit, Facebook, Pinterest; people were fascinated. If he'd just written "hey, car elevator, pretty cool," I myself might have enjoyed it and moved on. But phrased in the form of the question, I went into OCD mode, spent a couple hours of my work day trying to figure it out, got tremendously frustrated with myself, scrambled to catch up on whatever it is that I was doing in the first place, and eventually forgot about it.

Today I was looking at old films on the British Pathé site, an incredible collection of vintage newsreels, and I found one of a car elevator in Chicago. And it all came back to me, and the OCD switch went on again. Fortunately, the film provided a vital clue.

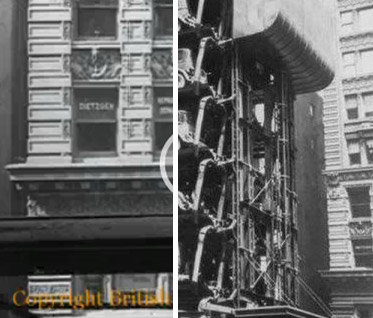

If you pause the video at 0:35, there's writing on the windows—I was able to make out the words "Dietzgen" and "Blue Prints." And the building looks exactly like the one in the background of the car elevator photo:

The asymmetrical concrete "bricks" are pretty distinctive, as are the patterned ones beneath the cornice, but I didn't know the building by sight, or whether it still existed. But "Dietzgen" was enough to go on.

The Eugene Dietzgen Company started in 1885 as an engineering supply house, and eight years later moved into manufacturing engineering and drafting supplies. Their second factory is a historical landmark, the Dietzgen Building, on the DePaul campus at 990 W. Fullerton. Urban Remains, the swanky antiques/artifact shop on Grand, had a Dietzgen drafting table for sale; their slide rules are apparently "popular with collectors"; some of their goods made a 1934 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. They're still around, if in name only, in the large-format graphics market. So the Eugene Dietzgen Company was a pretty big deal, with at least three locations in the city and offices around the country.

Which made the next step easy. In 1928, the Tribune ran a blurb noting that the Eugene Dietzgen Company "leased from the Lehmann estate the entire third floor of the Majestic theater building for a distributing branch." The Majestic Theater is now the Bank of America Theater, 22 W. Monroe St.

Third floor, right above the cornice. My family stayed in the Hampton Inn above the theater once; they might well have been in the old Dietzgen offices.

That would make the car elevator part of a building that no longer exists, if my spacial sense is right (which it often isn't): 33 W. Monroe St., constructed in 1980 and the former home of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. It lines up with the northeast corner of the Majestic Building, which the car elevator used to look out across the street on.

This may seem like the most boring thing in the world, though I have to say I'm pleased with myself. But there's an interesting little angle to the Eugene Dietzgen Company. Eugene was the son of Joseph Dietzgen, a German tanner-turned-Communist who read Marx and joined the Revolution of 1848, which got him exiled from Germany. So he moved to the U.S. and traveled the antebellum south, writing about slavery and lynching. He returned to Europe, building tanneries for the Czar, writing philosophy, and corresponding with Karl Marx, who called him "the philosopher of socialism"; Joseph Dietzgen is credited with coining the phrase "dialectical materialism" in 1887, though the idea itself was sort of floating around in the socialist ether of the times:

The "diamat" was a social theory coined by 19th century philosopher Joseph Dietzgen which emphasized commodities and the effects of their exchange over time. Dietzgen used his theory sparingly to explain the nature of socialism and social development, but it was never researched academically until the Soviet Union indoctrinated the philosophy.

Joseph returned to Germany and shortly thereafter dispatched his son Eugene to the States to avoid the draft. Eugene arrived in Chicago from New York in the early 1880s, and started his company here. Joseph followed in 1886… just in time for the Haymarket Bombing. In its wake, two employees of the radical German-language newspaper Chicagoer Arbeiterzeitung—typesetter Adolph Fischer and editor August Spies—were tried and executed for the bombing. Joseph Dietzgen temporarily filled Spies's position as editor of Arbeiterzeitung. He died two years later:

At home enjoying a cigar after a stroll in Lincoln Park, he was engaged in a "vivacious and excited" discussion of the "imminent collapse of capitalist production" when he suddenly stopped in mid-sentence, his hand uplifted—dead of "paralysis of the heart."

Joseph Dietzgen was buried in the German Waldheim Cemetary in Forest Park, alongside Spies, Fischer, and the other Haymarket Martyrs.