On Saturday my wife and I went for a very long walk for the sole purpose of getting out of the apartment. After three hours of walking, I was so happy to not be in the house that I suggested we stop at the neighborhood bar before finally going back home. When we got there, the Sox game was on, with the sound off.

It was the top of the ninth inning with the Sox at the plate, and the camera was lingering on Philip Humber in the dugout—cutting away for the pitch, then cutting right back to Humber. As a lifelong baseball fan, I knew there were two possible reasons for this: either Humber had totally screwed something up, and they were capturing the agony of defeat, or he was throwing at the very least a no-hitter. According to my phone, he was throwing a perfect game. You know what happened next: the check swing, Brendan Ryan arguing instead of running to first (somewhere, Tony LaRussa thought "I told you so"), the 21st perfect game in major league history.

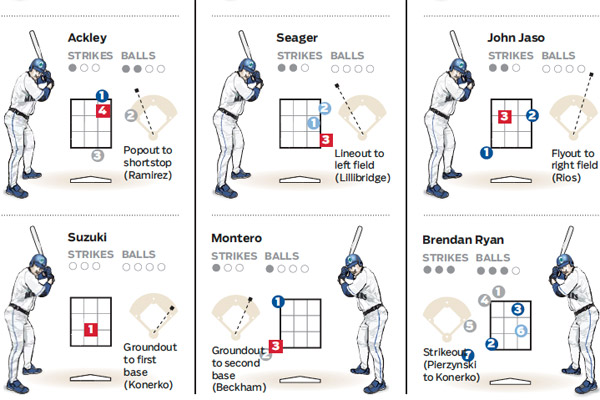

Phil Rogers immediately focused on the pitch that brought Humber his day of perfection, and his excellent season last year: the slider that he picked up after he got nowhere with the cut fastball, and the one that so flummoxed Ryan. The Trib's graphics department came up with a nice diagram of Humber's game, pitch by pitch, but it seems to undercount sliders, giving him 19 on the day. I think it comes straight from MLB's Gameday algorithm—it's the same number credited to him by the PitchFX site—which is a rough count and not always accurate. Buster Olney reports, via ESPN's stats and info department, that "Humber threw 32 sliders, resulting in 15 outs and six strikeouts. In his two starts this season, opponents are 1-for-22 with nine strikeouts in at-bats ending with a Humber slider."

32 sliders out of 96 pitches would be more in line with Humber's approach. Last year Humber threw 46 percent fastballs and 18 percent sliders. This year (in, granted, only two starts), Humber's at 40 percent fastballs and 38 percent sliders. He's also throwing his fastball harder in the young season, 91.7 mph compared to 90.5 mph. As Dave Cameron points out, Humber's move from the cut fastball to the slider means it's much slower:

When he got to Chicago, Humber was a guy who threw a 90-92 MPH fastball and an 86-88 MPH cutter. In his first two starts of 2012, he’s been a guy throwing a 90-94 MPH fastball and an 83-86 MPH slider. The differences in velocity and movement have given him distinct swing-and-miss weapons, and when combined with his change-up and curveball give him four pitches he can throw for strikes.

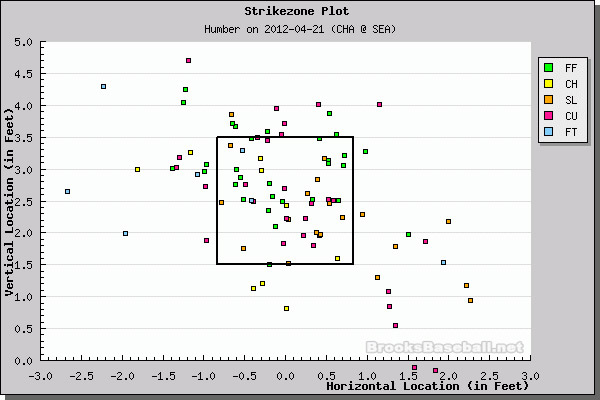

Humber's strikeout rate also went up over last year, but because it was concurrent with a change in his luck—a substantial rise in his batting average on balls in play—it looked like he got worse over last season, which wasn't necessarily the case. And the sliders that PitchFX did register were, on the whole, really accurate on Saturday:

Chris Cwik urges caution with Humber's slider count. The consensus is that the slider is the most stressful pitch to throw, because it's thrown sort of like a curve with the arm velocity of a fastball:

“Kids who threw the slider were at three times the risk of getting injured,” Register-Mihalik says. They reported more pain more often than other pitchers. One reason could be the mechanics necessary to throw a good slider. It requires a more violent arm motion; it’s like a combination of a curve and a fastball.

That's from a study of children up to age 14, not adults, but it's also generally believed that the slider is the hardest pitch on professional pitchers. I've even read suggestions that the sabermetrically inclined Tampa Bay Rays discourage their pitchers from throwing lots of sliders, and indeed Matt Garza's slider use went from 19 and 17 percent with the Twins, down to 13-14 percent with the Rays, and up to 24-25 percent after moving to the Cubs.

But for the time being, it's working, which is why Humber's perfect game isn't as unlikely as it first appeared. Going up against the Mariners didn't hurt:

Before Saturday, the Mariners' on-base percentage was .285 (compared to a major league average of .316). Only two teams had reached base less often to that point in the season, the Pirates and, sadly, the A's. It's early, you might say. Small sample, you might say. Well, last year, the Mariners' on-base percentage was .292, dead last in the majors, even behind all 16 teams who let their pitchers hit, and when they played at their pitching friendly home ballpark, where Saturday's game was played, that number dropped to .289. In 2010, the team OBP was .298, also dead last in the majors.

[snip]

A sub-.300 on-base percentage for an individual player, even one who contributes a lot on defense, is grounds for removal from the staring lineup (think Pedro Feliz, Rey Ordoñez, Jeff Mathis …). The Mariners' entire team has been that bad for three years running.

How bad is that? It's like an entire team of circa 2011 Gordon Beckhams, and at home an entire team of Brent Morels. It's 30 points below Juan Pierre's OBP last year.

But it shouldn't take anything away from Humber. The Mariners have had a horrible offense for years, and no one shut them down completely until Humber. It's part of why I think reports of the Sox's demise are exaggerated: they have five solid starting pitchers, including Humber, whose 2011 numbers may underestimate how good he is; and it's at least statistically unlikely that they'll have two of the worst everyday players in baseball this year, as Rios and Dunn are way outperforming last year's disaster so far. They're still not a great team, but if Danks, Floyd, Sale, Humber, and Peavy can stay healthy—watch that slider count—they have the makings of a reasonably competitive one.

Graphic: Chicago Tribune