Not long ago I was talking with a journalist from the generation before me, a Chicago expat, and we were marvelling at the attention the Trayvon Martin shooting has received. Each turn in the case has received attention around the world—Zimmerman's bond hearing is currently on the Tribune's main page, given prominence just under the state's most pressing fiscal issue.

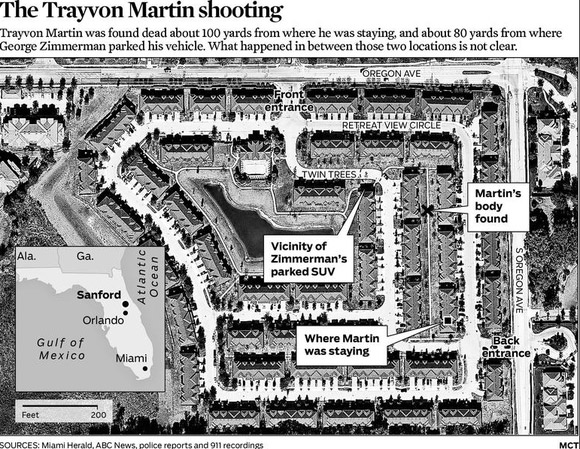

Eric Zorn has done an excellent job following the ins and outs; today's column is a moment-by-moment account, with a map of the crime scene:

So much of crime investigation turns on these open spaces in time and place: who was where, when. Lots of the coverage of the Martin shooting has inevitably focused on time, as Zorn's column does, but one of the more interesting pieces was written about place: the "gated" community Zimmerman and Martin's father live in—the latter on Retreat View Circle, covered by the "stand your ground" law:

Many have focused on a Florida law that allows wide firearms latitude in any self-defense situation; a lackluster investigation by police; and the racist overtones of the incident. But there is another factor: a poorly planned, exclusionary built environment.

As Robert Steuteville writes in "Gates, sprawl, and 'walking while black,'" Zimmerman's community is gated, but gates aren't impregnable. It's not just that anyone can walk into the gated community—it only keeps cars out—it's even more vulnerable to economic and social change:

The economic downturn is another factor. The Retreat at Twin Lakes is only six years old, but its property values have declined precipitously. Foreclosures forced owners to rent out to “low-lifes and gangsters,” one resident told the newspaper. The development is now “minority-majority”—49 percent non-Hispanic white, 23 percent Hispanic, 20 percent African-American, and 5 percent Asian. This story is partly about what happens to a gated development when residents find themselves on the same side of the gate as people they fear.

Steuteville raises good questions, but I disagree that Martin's death has much, if anything, to do with the environment. Vigilante justice and fear of the other are as old as America itself, and are found whenever socioeconomic borders collide: Chicago in particular has a long history of this kind of violence, which has historically been much more frequent in the least exclusionary environments urban planners have given us, like parks and public beaches.

In February, my former colleague Steve Bogira wrote an extraordinary, two-part series about the shooting death of Joe Henson at 5500 South Justine in 1970—a story that laid buried for four decades before Bogira chanced upon it. In the wake of the Martin shooting, it's resonant:

But there were still plenty of whites north of Garfield Boulevard when Mark and Jo Ann were attending Libby Elementary School, at 53rd and Loomis—on the "white" side of the boulevard. Mark, Jo Ann, Jeff, and their cousins and friends walked to school in a group, on a route prescribed by their elders because it avoided the whitest blocks: east down 56th Street to Bishop, north to Garfield Boulevard, east another block to the crossing guard at Loomis, north to the school. If the children strayed from the route and it was discovered, "that meant some skin off our behinds," Jo Ann says. Back then she chafed at what she considered her elders' overprotectiveness. "We were being conditioned to live in fear," she says. But now "I realize that they were being good guardians."

[snip]

Sherman Park had been a danger zone for blacks since they first dared using it when they were moving into the neighborhood in the late 1960s. In July 1970—a month after Joe Henson was killed—two black joggers, ages 24 and 25, were beaten there with baseball bats and sticks by a gang of 20 whites. "Hard-core whites feel they own the park," Sherman's supervisor told the black-owned Chicago Defender in a story about the beating.

"The Color of His Skin" is about a fight, grounded in racial tension, that spiraled out of control. And its reporting stemmed from an earlier story Bogira wrote, "The Price of Intolerance," about a nearly identical case, only with the races reversed:

Essie asked her sons and nephews not to retaliate. "We'll call the police, let them handle it," she'd say. Clark saw how well that worked. The police took their sweet time arriving, and, by his estimation, couldn't catch a cold. He was willing to follow his mother's directives only so far. As the assaults continued, he positioned a large box behind the hedges in front of the house, and he and his brothers and cousins filled it with bricks and rocks "so we could return fire" when attacked. "We had moved in this neighborhood to try to create a life for ourselves," he says. "I wasn't going to let anything shatter that."

People will find ways of building walls to keep others out—gates, boxes filled with bricks and rocks, gang-controlled territories, block clubs, highways, urban renewal, redlining. Sometimes the violence is interracial, sometimes it's intraracial, sometimes it's much more complicated.

On the other hand, the environment that the shooting took place has very much to do with the coverage ("welcome to gate-minded America"). Gated communities are still quite novel, with a roughly estimated population of four to eight million: 1.3 to 2.6 percent of the population. Despite having been to almost every state in the lower 48, including some of its richest and poorest communities, I've never been in one; I don't recall ever even having passed one. For me, they're as much the Other as anywhere else in America. They're seemingly exclusionary and alien, but one of the fascinations and fears of the Trayvon Martin shooting is that many of them, it seems, are neither.

Map: Chicago Tribune