photo: courtesy divvy

Got seven bucks? These are your wheels, for 24 hours, starting this summer.

Chicago's bike-sharing dreams started in Paris, when Mayor Richard M. Daley hopped on a Velib bicycle and declared bike-sharing the future of city commuting. Six years later, Mayor Rahm Emanuel appears close to making his predecessor’s ambition a reality.

At a press conference this morning, members of the Chicago Department of Transportation announced concrete plans for Divvy, the city’s first major bicycle-sharing rental program, which they expect to launch officially in several weeks. (Its new website and twitter feed are both live.)

There have been plenty of speed bumps along the way. After Daley’s European trip, Chicago requested proposals from private partners to build out and run a 1,500-bike system, but only two potential operators came forward. Both submitted plans that would have required the city to front too much of the cost.

It wasn’t until last April when the city council finally approved a bike-share contract with Alta Bicycle Share, a company based Portland, Oregon. Further logistical delays, along with complaints of dirty dealings during the bidding process, stemming from Transportation Commissioner Gabe Klein’s old relationship with the city’s new collaborator, followed.

But now it seems like the things are coming into place:

Hundreds of three-speed bikes painted "Chicago blue" will hit the streets in June when the city debuts a bicycle-sharing rental program that originally was set to launch last summer, officials are expected to announce Thursday.

Operating under the name Divvy, which is intended to convey the idea of sharing bikes, the system will start out with about 75 solar-powered docking stations in the downtown and River North areas and expand within a year to 400 stations and about 4,000 bicycles covering much of the city, according to the Chicago Department of Transportation. […]

Alta Bicycle Share, based in Portland, Ore., will operate the program year-round. It is budgeted to cost about $22 million and is "expected to pay for itself" over time, said Sean Wiedel, an assistant commissioner at CDOT who oversees the bike-sharing program. Federal grants for projects that cut traffic congestion and improve air quality are providing the initial funding.

Like in a growing number of North American cities, Divvy will operate essentially like car-sharing programs. For an annual membership of $75, or a daily pass costing $7, a user can swipe a key (or purchase a pass at a kiosk) to unlock a three-speed bike, then ride that bike until her final destination, where she will be able to park it and go on her merry way. The first 30 minutes are free, and hourly rental fees kick in if the bike stays out longer.

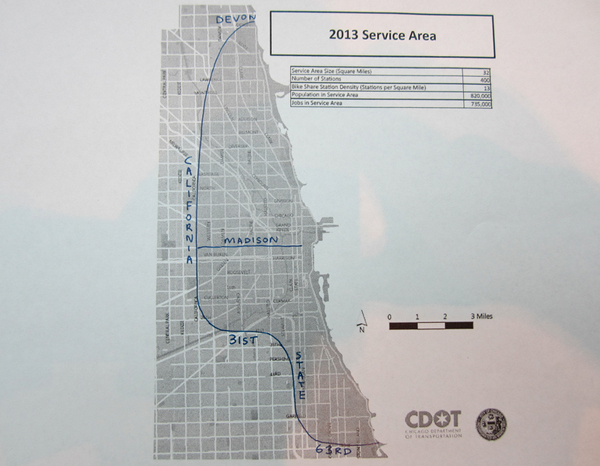

Last spring, John Greenfield posted maps of the territory Chicago’s plan will eventually cover—north as far as Devon, west to California, and south to 63rd:

graphic: chicago department of transportation / trapgosh

Washington D.C., where Klein worked before joining the Emanuel administration, serves as both a cautionary and instructive example of how a bike-sharing system should be run. In 2008, the District—in conjunction with communications conglomerate Clear Channel, who maintained the system as part of a 20-year bus shelter contract—debuted Smartbike, with 120 bikes on ten racks.

It flopped pretty hard.

What went wrong?

- Clear Channel promoted it terribly.

- The baskets were flimsy, which made running errands difficult.

- The stations were expensive to build but sold only long-term memberships and didn’t accept credit cards, which made the bikes worthless to DC’s many tourists.

- There just weren't many bikes and places to park them, which limited the system’s utility.

Each SmartBike was ridden once per day, according to June 2010 report, compared to five times per day in Montreal's Bixi system.

Instead of shutting it down entirely, Klein and company redoubled their bike-share efforts, finding local government partners and grants to fund a more robust network. They also modeled stations after those in Montreal, which were solar-powered, modular, and easy to erect. Riders, in turn, flocked:

The one anomaly appears to be in Washington D.C., where a concentrated downtown, booming tourism and government-funded expansion has the program supporting itself—without advertising or sponsorships. Each year the program collects about $3 million in revenue, which goes into a “rainy day fund” because government funding still covers costs, said project manager Chris Holben.

The program now boasts 1,800 bikes and 153 stations—up from an initial fleet of 1,100 and 100 stations when it started in September 2010—and 22,000 subscribers.

Many of the principles that worked well in the nation’s capital are being applied here in Chicago, though it’s yet to be seen whether the concept will catch on in a city that’s still developing its cycling infrastructure and culture. Funding the program primarily through federal grants, meanwhile, is understandable but risky: You avoid a problem like Toronto is facing, where the city is backstopping a loan that doesn’t look likely to be reimbursed, but government grants sometimes disappear quickly and without notice.

Ron Burke, executive director of Active Transportation Alliance, is bullish. Bike-sharing, he said this morning, “will be perfect for trips under a few miles that are too short to wait for a bus, and too far to walk, and it will be much cheaper than a taxi.”

If you take a spin starting in June, just don’t leave one parked outside of a designated dock—the cost of replacing a stolen one is $1,200.