Terrence Antonio James/Chicago Tribune

Memorial to Hadiya Pendleton, Harsh Park, January 31, 2013

Yesterday, Michelle Obama was at Harper High to talk gun violence and to push for solutions—"Hadiya Pendleton was me… but I got to grow up." Less noticed, but on the same day, the Rev. James Meeks wrote an editorial in the Tribune on his own plans: "On April 18, I will convene fellow members of the clergy to finalize a program targeting African-American males ages 15 to 35 to, among several initiatives, help them attain GEDs, find jobs and kick their drug addictions."

There's a reason he's targeting that particular age group:

To reverse the culture of violence that is leaving a trail of bodies across the city, innocents and perpetrators alike, we must target the inherent social and economic disparities disproportionately impacting African-American men and boys. The numbers bear this out. According to analysis of police data, of the more than 500 reported homicides in Chicago last year, 361 of the victims were African-American males; 287 were ages 15 to 35.

Meeks contrasts this to when he was a kid (he was born in 1956), when "a teenager getting hold of a gun and firing into a crowd of his peers was unthinkable." I was curious about this. When Meeks was a kid, Chicago's homicide rate was already increasing. When he was 10, it began a massive increase that we've only recently come down from. So, as usual, I'm initially skeptical when people describe how things were better back in their day.

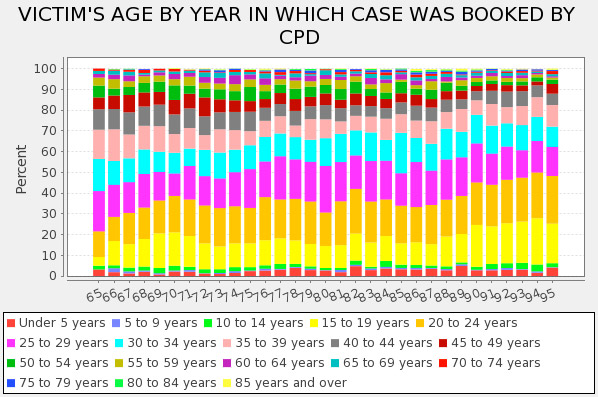

But that doesn't mean Rev. Meeks is wrong about what ages are getting killed, and what ages are doing the killing. And the National Archive of Criminal Justice Data allows us to check the numbers on homicide in Chicago, from 1965-1995, at a glance. And Meeks has a point: in that 30-year period, the demographics of African-American homicide victims changed considerably.

In 1965, victims from 15-24 years old made up 17 percent of the total. In 1975, 29 percent. In 1985, 29 percent. In 1995, 42 percent. In 2005, 40 percent. Last year, it was 44 percent.

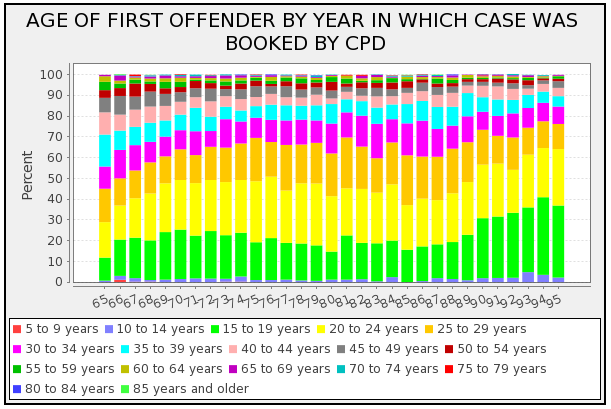

The change in offender age is pretty similar. In 1965, offenders from ages 15-24 made up about 30 percent of all homicide-level offenders; in 1995, it was about 65 percent.

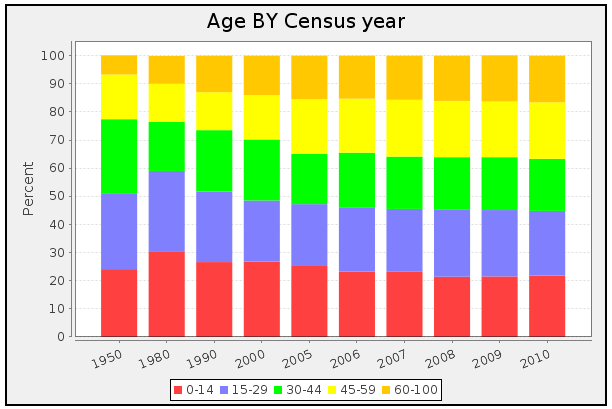

What explains it? Mere age demographics don't seem to, not entirely. From 1980-2010 the black population in Chicago got older. In 1980 and 1990 it was heavily weighted towards youth (about half the population was below 30), but that's come down since. 15-29 is still the largest age group, but not by as much.

Looking at all this, I can't help but wonder if D. Bradford Hunt's thesis in Blueprint for Disaster: The Unraveling of Chicago Public Housing has anything to do with it. One of Hunt's main arguments is that public housing had a freakishly high ratio of youths to adults, leaving the former with a troublesomely low exposure to the guidance of the latter.

* In 1970, Chicago had a youth (under 21) to adult ratio of 0.58, slightly higher than in 1960, much lower than it was in 1890 (0.75). In the slums in 1910, it was 0.97—identical to Park Forest in 1960.

* But in CHA housing in 1960, it was 1.77. In 1970, that climbed to 2.39. In the Robert Taylor Homes in 1965, it was 2.86. Pruitt-Igoe, the infamous St. Louis housing project that became a symbol of the concept's failure, had a ratio of 2.63 in 1968. As Hunt writes, "CHA planners produced communities with youth-adult ratios several magnitudes greater than any previously seen in the urban experience."

This didn't happen in a vacuum. Lots of other things changed during this time—the urban flight of middle-class families and jobs, demographic changes that Meeks brings up, the increasing physical mismanagement of the projects, and the high ratios of youths to adults were driven, in part, by the CHA's desire to house large families.

But Hunt makes a compelling case that the specific age demographics of public housing made things worse. Hunt quotes Jane Jacobs on where the flaw was:

In a telling and neglected passage, Jacobs maintains that "planners do not seem to realize how high a ratio of adults is needed to rear children at incidental play… only people rear children and assimilate them into civilized society." Jacob's use of the words "ratios" and "people" is significant: the daily interactions between children and adults who are nonparents are an important force in creating the boundaries of expected social behavior: "In real life, only from the ordinary adults of the city sidewalks do children learn—if they learn it at all—the first fundamental of successful city life: People must take a modicum of personal responsibility for each other even if they have no ties to each other. This is a lesson nobody learns by being told. It is learned from the experience of having other people without ties of kinship or close friendship or formal responsibility to you take a modicum of public responsibility for you."

Related: At the Chicago Reporter, Megan Cottrell looks at the Urban Institute's new study of public housing in Chicago and asks: Did Chicago's Plan for Transformation succeed?; from earlier this year, Alden K. Loury wrote that "youths are the no. 1 target in Chicago's homicide epidemic."