I've been a Cardinals fan for as long as I can remember, mostly for the reasons Rob Mitchum lays out here: the Cardinals of the mid-1980s were cool, relying on a charismatic, athletic version of small-ball that appealed to my young attention span.

But decades before the miracle of MLB.tv, the lens I had to see them from was WGN. And I'm hardly alone in this; the immense reach of the Cubs' radio and television empires meant that those of us growing up in the vast baseball nowheres between big cities got our only glimpses of major-league baseball via the lovable losers.

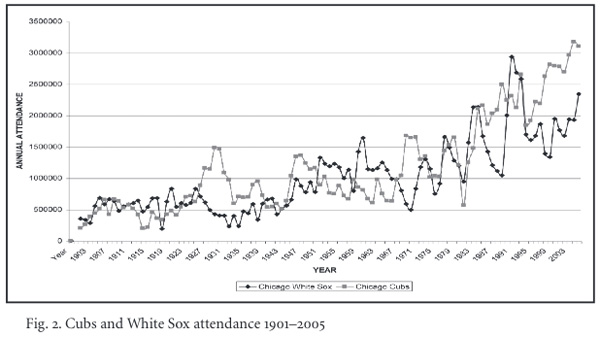

Then I came to Chicago and married into a Sox family; if anyone, I should resent that Chicago's a Cubs town. But that's the truth. It is, however, not nearly as long-established a truth as I'd assumed. That's because Chicago's been a Cubs town only as long as I've been conscious of baseball, which is to say around 1986, when the teams' fortunes began to diverge:

The Sox got a big boost around 1991 when the Cell was built, but shortly thereafter attendance moves strikingly back to its old trend (it also appears to have eaten into the Cubs' attendance, though they were pretty mediocre at that point). Even the Sox' World Series victory wasn't enough to catch the Cubs, who have been thriving in the stands as they've struggled on the field.

Wrigley Field, celebrating its 100th birthday today, gets much of the credit. It's a landmark, both literally and figuratively; it's a tourist destination; it's in the middle of a dense neighborhood instead of highway, rails, and parking lots.

But the teams' attendance has varied over the years; until the past couple decades, the teams traded positions for most of the 20th century, so it's unlikely that Wrigley explains everything.

That graph comes from "A Tale of Two Teams: A Comparison of the Cubs and White Sox in Chicago," which attempts to get to the bottom of the question. The authors' overarching conclusion is that, for all the fame Bill Veeck made for himself with the Sox, it was William Wrigley who established the foundation for the Cubs' long-run success.

The Cubs' attendance spikes in the late 1920s and the early 1940s. In that first period, Wrigley had the insight that giving the Cubs' radio rights away at modest sums—less than the White Sox—would not eat into ticket sales, and instead would sustain interest in the team. (This is the lesson that took the media-shy Blackhawks decades to learn.)

Phil Wrigley continued that into the television era: "Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Phil Wrigley sold the Cubs TV rights for minimal fees, reasoning that he was creating fans. As late as 1963, Cubs rights for both radio and television cost only $500,000… $350,000 less than the fees earned by the cross-town White Sox."

(The White Sox mostly outdrew the Cubs during the 1950s, but the Cubs were awful, with one .500 season—specifically .500, not one win above—from 1946-1963.)

In the 1980s, another media shock would boost the Cubs. Beginning in 1978, WGN became a superstation carried on cable networks, which had been around for decades but greatly expanded in the 1980s, reaching 65 percent of households by 1992. The Cubs also added night games in 1988; in that sense, Lee Elia was farsighted in pointing out that "eighty-five percent [of key demographic members] are earning a living" while "the other fifteen percent come out here."

Around that time—specifically 1982—the Sox were screwing around with the disastrous SportsVision pay-per-view system, which not only cost them reach, but the legendary Harry Caray: "Logan’s book quotes Caray as saying 'that’s when I made up my mind to leave. They were talking about maybe reaching 50,000 homes on pay TV instead of the 22 million people who watch the Cubs on WGN.'" As the Cubs were establishing themselves as America's team, the White Sox took their ball and went home.

One more change might play a role that's more intertwined with Wrigley itself. From 1990-2000, Lake View's literal fortunes improved immensely. The median family income increased from $59,677 to $84,458—a 42 percent increase. The population of residents with an associate's, some college but no degree, a high school diploma, or no diploma at all all fell. Meanwhile, the neighborhood added 10,607 residents with bachelor's degrees and another 5,000 with a graduate or professional degree. The population barely budged, but the disposable income in the neighborhood exploded. (Lincoln Park saw similar change in educational attainment, and the median family income increased from almost $100,000 to $132,000.)

Meanwhile, in Bridgeport, the median income increased a mere 10 percent; the biggest increase in educational attainment was "some college, no degree." Both people and families below the poverty line increased.

Wrigley Field has deservedly become one of the shrines of baseball and a draw in its own right. But behind that is a history of marketing and demographic change that has, now and in the foreseeable future, tied the city's hopes to a historically hopeless franchise.